AI-Driven Drug Synthesis: Machine Learning for Predicting Reaction Yields and Optimizing Conditions

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) in predicting chemical reaction yields and optimizing synthesis conditions for drug development.

AI-Driven Drug Synthesis: Machine Learning for Predicting Reaction Yields and Optimizing Conditions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) in predicting chemical reaction yields and optimizing synthesis conditions for drug development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and pharmaceutical professionals, it explores foundational AI concepts, delves into specific methodologies like retrosynthetic analysis and reaction prediction models, and addresses critical implementation challenges such as data quality and model generalization. The review further synthesizes validation frameworks and comparative analyses of ML algorithms, offering a roadmap for integrating data-driven approaches to accelerate pharmaceutical innovation, enhance efficiency, and reduce environmental impact.

The New Paradigm: How AI is Revolutionizing Pharmaceutical Synthesis

Traditional drug synthesis has long been characterized by a laborious, time-consuming, and economically challenging process. The prevailing model faces a critical sustainability crisis, often referred to as "Eroom's Law" – the observation that the cost of developing a new drug increases exponentially over time, despite technological advancements [1]. This introduction details the economic, procedural, and scientific hurdles of conventional approaches, setting the stage for the transformative potential of machine learning-driven methodologies.

The Economic and Temporal Burden of Drug Development

The traditional path from a laboratory hypothesis to a market-approved drug is a marathon of extensive testing and validation. The following table quantifies the immense burden of this process.

Table 1: The Economic and Temporal Challenges of Traditional Drug Synthesis

| Metric | Value in Traditional Synthesis | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Average Timeline | 10 to 15 years [2] [1] | Linear, sequential stages where each phase must be completed before the next begins, creating significant delays. |

| Average Cost | Exceeds $2.23 billion per approved drug [1] | Costs are compounded by high failure rates, with the vast majority of candidates failing in late-stage trials. |

| Attrition Rate | Only 1 out of 20,000-30,000 initially screened compounds gains approval [1] | A "make-then-test" paradigm leads to massive resource expenditure on ultimately unsuccessful candidates. |

| Return on Investment (ROI) | Has reached record lows (e.g., 1.2% in 2022) [1] | The soaring costs and high failure rates make the traditional model economically unsustainable. |

The root of this inefficiency lies in the combinatorial explosion of chemical space, which contains over 10â¶â° synthesizable small molecules, and the severely limited throughput of empirical, physical screening methods that can only evaluate a tiny fraction of these candidates [3].

The Traditional Drug Synthesis Workflow: A Linear Gauntlet

The conventional drug development pipeline is a rigid, sequential series of stages, each acting as a gatekeeper to the next. This structure, while designed to ensure safety and efficacy, also creates significant bottlenecks and siloes information.

Diagram 1: Traditional Drug Synthesis Workflow

This linear workflow creates a system where the cost of failure is maximized at the latest stages. A drug that fails in Phase III clinical trials represents over a decade of work and billions of dollars in sunk costs, with minimal opportunity to use the learnings to inform new discovery cycles [1].

Key Bottlenecks in Conventional Synthesis and Optimization

The "Make-Then-Test" Paradigm and Reaction Optimization

A fundamental bottleneck in the discovery phase is the "make-then-test" approach. Chemists must synthesize physical compounds before their properties and yields can be evaluated, a process that is inherently slow and resource-intensive [1]. When studying a new reaction system, chemists face a vast "reaction space" defined by variables such as catalysts, ligands, additives, and solvents. For example, a single Suzuki coupling reaction space can comprise 5,760 unique combinations [4]. Exploring this space manually is impractical, relying heavily on researcher expertise and intuition, which often leads to the oversight of potentially viable high-yielding conditions [4].

Limitations of Early Technological Solutions

Technologies like High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) emerged to accelerate this process by running many reactions in parallel [4]. While powerful, HTE infrastructure is prohibitively expensive for most laboratories, thus failing to fully democratize or solve the scalability issue of reaction optimization [4]. This leaves a critical need for methods that can efficiently navigate large reaction spaces with minimal experimental data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

The following table outlines essential reagent solutions and their functions in traditional drug synthesis, particularly in the early discovery stages.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Drug Synthesis

| Reagent / Material | Function in Drug Synthesis |

|---|---|

| Catalysts & Ligands | Facilitate key bond-forming reactions (e.g., Palladium-catalyzed C-N or C-C couplings) and control stereochemistry [4]. |

| Solvents & Additives | Create the reaction environment, stabilize transition states, influence reaction rate, and optimize yield [4]. |

| Building Blocks | Provide the core molecular scaffolds and functional groups that are assembled into more complex drug-like molecules. |

| Target Engagement Assays (e.g., CETSA) | Validate direct binding of a drug candidate to its intended protein target within intact cells, bridging the gap between biochemical potency and cellular efficacy [5]. |

| Isoeuphorbetin | Isoeuphorbetin, MF:C18H10O8, MW:354.3 g/mol |

| 1-Azido-4-bromo-2-fluorobenzene | 1-Azido-4-bromo-2-fluorobenzene, CAS:1011734-56-7, MF:C6H3BrFN3, MW:216.01 g/mol |

Paving the Way for a New Paradigm

The challenges outlined above—prohibitive costs, extended timelines, high attrition, and inefficient "make-then-test" cycles—collectively define the pressing need for a transformation in drug synthesis. The linear, physically constrained traditional model is fundamentally ill-suited to navigating the vast complexity of chemical and biological space. This context creates a compelling mandate for the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning, which promise to invert the traditional workflow into an intelligent, predictive, and data-driven "predict-then-make" paradigm, thereby directly addressing the core inefficiencies that have long plagued drug development [1].

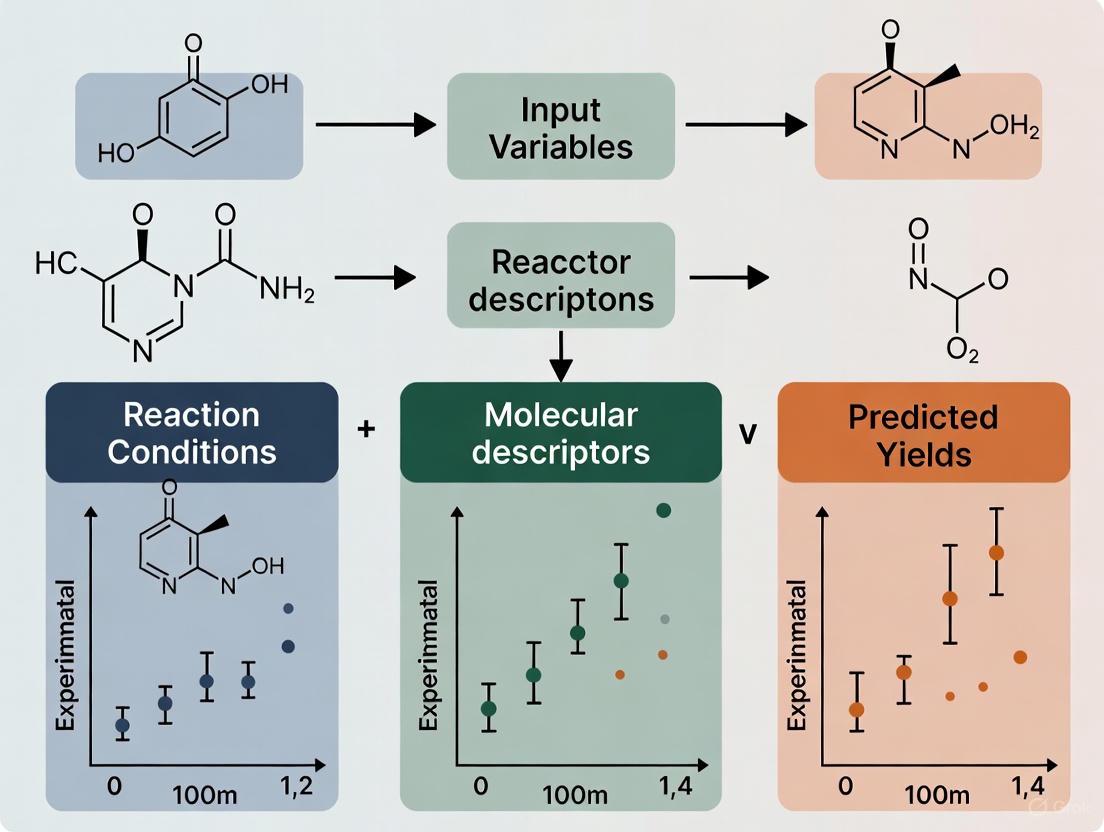

The optimization of chemical reactions is a fundamental task in organic synthesis and pharmaceutical development, with reaction yield serving as a critical metric for evaluating experimental performance. Traditional methods for yield prediction rely heavily on chemists' domain knowledge and extensive wet-lab experimentation, which are often time-consuming, labor-intensive, and limited in their ability to explore vast reaction spaces. The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), has introduced transformative approaches to this challenge. By leveraging computational models to find patterns in chemical data, AI enables more efficient prediction of reaction outcomes and accelerates the exploration of viable reaction conditions.

This application note details cutting-edge methodologies at the intersection of machine learning and cheminformatics for predicting chemical reaction yields. We focus on two particularly impactful frameworks: the RS-Coreset method for efficient exploration with limited data, and the ReaMVP framework, which utilizes large-scale multi-view pre-training for enhanced generalization. The protocols and reagents outlined herein provide researchers and drug development professionals with practical tools to implement these AI-driven approaches in their reaction optimization workflows.

Key Methodologies and Comparative Analysis

RS-Coreset for Small-Scale Data: This active representation learning method addresses the challenge of predicting reaction yields with limited experimental data. The core idea involves constructing a small but representative subset (a "coreset") of the full reaction space to approximate yield distribution. This interactive procedure combines deep representation learning with a sampling strategy that selects the most informative reaction combinations for experimental evaluation, significantly reducing the experimental burden required to explore large reaction systems. This approach is particularly valuable in resource-constrained environments where high-throughput experimentation is not feasible [4].

ReaMVP for Large-Scale Pre-training: The Reaction Multi-View Pre-training (ReaMVP) framework represents a different paradigm, leveraging large-scale data and self-supervised learning to achieve high generalization capability. Its key innovation lies in modeling chemical reactions through both sequential (1D SMILES) and geometric (3D molecular structure) views, capturing more comprehensive structural information. The two-stage pre-training strategy first aligns distributions across views via contrastive learning, then enhances representations through supervised learning on reactions with known yields. This approach demonstrates particularly strong performance in predicting out-of-sample reactions involving molecules not seen during training [6].

Quantitative Comparison of Methodologies

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of AI Approaches for Reaction Yield Prediction

| Methodological Feature | RS-Coreset Approach | ReaMVP Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Requirement | Small-scale (2.5-5% of full space) [4] | Large-scale pre-training (millions of reactions) [6] |

| Key Innovation | Active learning with reaction space approximation [4] | Multi-view learning (1D sequence + 3D geometry) [6] |

| Representation Learning | Deep representation learning guided by interactive sampling [4] | Two-stage pre-training with distribution alignment and contrastive learning [6] |

| Experimental Burden | Low (requires only small subset of experiments) [4] | High initial data collection, but low marginal cost for predictions [6] |

| Generalization Strength | Effective within defined reaction space [4] | Superior for out-of-sample predictions [6] |

| Reported Performance | >60% predictions with <10% error (5% data sampling on B-H dataset) [4] | State-of-the-art on benchmarks; enhanced out-of-sample ability [6] |

| Ideal Use Case | Reaction optimization with limited budget/experiments [4] | High-throughput settings requiring prediction on novel reactions [6] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: RS-Coreset for Reaction Yield Prediction with Limited Data

Principle: This protocol implements an active learning workflow that iteratively selects informative reaction combinations for experimental testing to build a predictive model of reaction yields while minimizing experimental effort. The method is particularly valuable for exploring large reaction spaces where comprehensive experimentation is prohibitive [4].

Procedure:

- Reaction Space Definition: Define the scope of reactants, products, additives, catalysts, and other relevant components to construct the full reaction space [4].

- Initial Random Sampling: Select an initial small set of reaction combinations (e.g., 1-2% of the space) uniformly at random or based on prior literature knowledge [4].

- Iterative Active Learning Cycle: Repeat the following steps until model performance stabilizes or experimental budget is exhausted:

- Yield Evaluation: Perform experimental reactions on the selected combinations and record precise yields [4].

- Representation Learning: Update the representation space using the newly acquired yield information to refine the model's understanding of structure-yield relationships [4].

- Data Selection: Apply a maximum coverage algorithm to select the next set of reaction combinations that provide the most information gain for the model [4].

- Full Space Prediction: Use the trained model to predict yields for all combinations in the reaction space and identify high-yielding conditions for validation [4].

Technical Notes:

- The RS-Coreset method has been validated on public datasets including Buchwald-Hartwig C-N coupling (3,955 combinations) and Suzuki-Miyaura C-C coupling (5,760 combinations), achieving promising predictions with only 5% data sampling [4].

- Implementation requires integration between computational selection algorithms and experimental execution, with typical iteration cycles ranging from 3-6 rounds depending on reaction space complexity.

Protocol 2: ReaMVP Multi-View Pre-training for Yield Prediction

Principle: This protocol implements a comprehensive pre-training strategy that leverages both sequential and geometric views of chemical reactions to learn generalized representations for accurate yield prediction, particularly for out-of-sample reactions [6].

Procedure: Stage 1: Self-Supervised Multi-View Pre-training

- Data Preparation: Collect large-scale reaction data (e.g., USPTO database with ~1.8 million reactions) and preprocess by removing duplicates and invalid reactions [6].

- Multi-View Representation:

- Consistency Learning: Employ distribution alignment and contrastive learning to capture the consistency between sequential and geometric views of the same reactions [6].

Stage 2: Supervised Pre-training with Yield Data

- Yield-Augmented Dataset Curation: Combine reactions with known yields from multiple sources (e.g., USPTO and CJHIF datasets), ensuring balanced yield distribution [6].

- Supervised Fine-tuning: Further pre-train the model to predict yields using the augmented dataset, enhancing task-specific representation capability [6].

Stage 3: Downstream Fine-tuning

- Benchmark Dataset Application: Fine-tune the pre-trained model on specific yield prediction benchmarks (e.g., Buchwald-Hartwig or Suzuki-Miyaura datasets) [6].

- Out-of-Sample Evaluation: Assess model performance on carefully constructed test sets containing molecules not present in training data [6].

Technical Notes:

- The ETKDG algorithm for conformer generation should use default parameters as implemented in RDKit [6].

- The two-stage pre-training approach addresses data distribution biases in public datasets, particularly the under-representation of low-yield reactions [6].

- This protocol requires significant computational resources for pre-training but offers exceptional transfer learning capability for downstream prediction tasks.

Workflow Visualization

RS-Coreset Active Learning Workflow

ReaMVP Multi-View Pre-training Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational and Experimental Reagents for AI-Driven Reaction Prediction

| Research Reagent | Type | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Software Library | Cheminformatics toolkit for molecule manipulation, descriptor calculation, and conformer generation [6] | Generating 3D molecular conformers via ETKDG algorithm [6] |

| SMILES/SMARTS | Molecular Representation | String-based representations of chemical structures for sequential modeling [6] | Encoding reactions as input for sequence-based neural networks [6] |

| Molecular Descriptors | Feature Set | Quantitative representations of molecular properties for machine learning [6] | Creating fixed-length feature vectors for traditional ML models [6] |

| USPTO/CJHIF Datasets | Data Resource | Large-scale reaction databases for model pre-training [6] | Providing millions of reactions for self-supervised learning [6] |

| Buchwald-Hartwig Dataset | Benchmark Data | High-throughput experimentation results for C-N coupling reactions [4] [6] | Evaluating model performance on 3,955 reaction combinations [4] |

| Suzuki-Miyaura Dataset | Benchmark Data | High-throughput experimentation results for C-C coupling reactions [4] [6] | Validating model generalization on 5,760 combinations [4] |

| ETKDG Algorithm | Computational Method | Knowledge-based approach for molecular conformer generation [6] | Creating 3D geometric structures for reaction components [6] |

| Coreset Algorithms | Sampling Method | Techniques for selecting representative subsets of large datasets [4] | Identifying informative reactions for experimental testing [4] |

| 1-Amino-2-methyl-4-phenylbutan-2-ol | 1-Amino-2-methyl-4-phenylbutan-2-ol | Bench Chemicals | |

| Boc-Glu-Lys-Lys-AMC | Boc-Glu-Lys-Lys-AMC, MF:C32H48N6O9, MW:660.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The integration of machine learning, deep learning, and cheminformatics has created powerful new paradigms for predicting chemical reaction yields. The RS-Coreset and ReaMVP frameworks represent complementary approaches addressing different resource constraints and application scenarios. RS-Coreset provides an efficient pathway for reaction optimization with limited experimental capacity, while ReaMVP leverages large-scale pre-training for superior generalization on novel reactions. Both methodologies demonstrate the transformative potential of AI in accelerating chemical research and drug development. As these technologies continue to evolve, they promise to further compress discovery timelines, expand explorable chemical space, and enhance our fundamental understanding of reaction mechanisms.

The application of artificial intelligence (AI) in predicting chemical reaction yields and conditions represents a paradigm shift in chemical research and pharmaceutical development. Traditional reaction optimization is often a time-consuming and resource-intensive process, relying heavily on empirical methods and expert intuition. AI techniques, particularly neural networks and reinforcement learning, are now enabling a transition from this "make-then-test" approach to a predictive "in-silico-first" paradigm [7]. This transformation is crucial for addressing the systemic crisis in pharmaceutical research and development (R&D), where developing a new drug typically requires over 10 years and exceeds $2 billion, with only a minute fraction of initially promising compounds ultimately receiving regulatory approval [7]. Machine learning (ML) algorithms can analyze complex, high-dimensional relationships in chemical data that surpass human cognitive capabilities, identifying patterns, predicting outcomes, and generating novel hypotheses that can significantly accelerate the development lifecycle [8] [7].

The integration of AI is particularly valuable for exploring vast "reaction spaces" - the multidimensional arrays of possible combinations involving reactants, catalysts, ligands, additives, and solvents that define a chemical system [4]. The size of such spaces can be enormous; for example, the publicly available Suzuki coupling dataset features a reaction space of 5,760 unique combinations [4]. High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) can generate data for these spaces but remains prohibitively expensive for most laboratories [4]. AI techniques address this fundamental challenge by enabling accurate yield predictions and optimal condition identification from limited experimental data, dramatically reducing the experimental burden and cost while minimizing the risk of overlooking high-performing reaction conditions [8] [4].

Neural Networks for Molecular Representation and Yield Prediction

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for Molecular Structure Encoding

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as particularly powerful tools for chemical reaction yield prediction due to their innate ability to operate directly on molecular graph structures [9]. In this representation, molecules are treated as graphs where nodes correspond to heavy atoms and edges represent chemical bonds. Each node vector encompasses atomic features such as atom type, formal charge, degree, hybridization, number of adjacent hydrogens, valence, chirality, associated ring sizes, electron acceptor/donor characteristics, aromaticity, and ring membership [9]. Edge vectors encode bond-specific information including bond type, stereochemistry, ring membership, and conjugation status [9].

This graph-based approach preserves the topological structure of molecules, allowing GNNs to learn rich, context-aware representations that capture complex chemical environments. The GNN processes these molecular graphs through multiple layers of neural network operations that aggregate and transform feature information from neighboring atoms and bonds, effectively learning meaningful chemical representations that predict reaction behavior and yield [9]. For reaction yield prediction, the model takes a chemical reaction ((\mathcal{R}, \mathcal{P})) as input, where (\mathcal{R}) represents the set of reactant molecular graphs and (\mathcal{P}) represents the product molecular graph, and outputs a predicted yield value [9].

Addressing Data Scarcity through Transfer Learning

A significant challenge in applying deep learning to chemical reaction yield prediction is the performance degradation that occurs when models are trained on insufficient or non-diverse datasets [9]. To address this, researchers have developed innovative transfer learning techniques that pre-train models on large-scale molecular databases before fine-tuning them on specific reaction yield prediction tasks.

One such method, MolDescPred, defines a pre-training task based on molecular descriptors [9]. The approach involves:

- Calculating Molecular Descriptors: Using the Mordred calculator to generate 1,613 2D molecular descriptors for each molecule in a large database [9].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Applying Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the high-dimensional descriptor vectors while preserving most of the original variance [9].

- Pre-text Task Definition: Using the reduced-dimensionality vectors as pseudo-labels, then pre-training a GNN to predict these pseudo-labels from input molecular graphs [9].

- Fine-tuning: The pre-trained GNN is subsequently fine-tuned on the specific reaction yield prediction task, demonstrating significantly improved performance, especially when the reaction training dataset is limited [9].

This approach leverages the fundamental chemical information embedded in molecular descriptors to create a better-initialized model that requires less reaction-specific data for effective fine-tuning, substantially enhancing prediction accuracy in data-scarce scenarios [9].

Small-Data Strategies with Active Learning

For situations where even collecting a moderate-sized training dataset is challenging, active learning strategies coupled with neural networks offer powerful alternatives. The RS-Coreset method is specifically designed to optimize reaction yield prediction while minimizing experimental burden [4]. This approach iteratively selects the most informative reaction combinations for experimental testing, building an accurate predictive model from minimal data.

The RS-Coreset protocol operates through an iterative cycle [4]:

- Yield Evaluation: Selected reaction combinations are experimentally tested, and their yields are recorded.

- Representation Learning: The model updates its internal representation of the reaction space using the newly acquired yield data.

- Data Selection: Using a maximum coverage algorithm, the method selects the next set of reaction combinations predicted to be most informative for model improvement.

This active learning framework has demonstrated remarkable efficiency, achieving promising prediction results while querying only 2.5% to 5% of the total reaction combinations in a given space [4]. For example, on the Buchwald-Hartwig coupling dataset with 3,955 reaction combinations, the method achieved accurate predictions (over 60% with absolute errors <10%) using only 5% of the available data for training [4].

Table 1: Neural Network Approaches for Reaction Yield Prediction

| Technique | Data Requirements | Key Advantages | Representative Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Moderate to Large datasets | Native processing of molecular structure; High expressive power | Significant improvement over non-graph methods [9] |

| Transfer Learning (MolDescPred) | Can work with small datasets | Leverages knowledge from molecular databases; Reduces needed reaction data | Effective even with insufficient training data [9] |

| Active Learning (RS-Coreset) | Very Small datasets (2.5-5%) | Minimizes experimental burden; Focuses on most informative samples | >60% predictions with <10% error using only 5% of data [4] |

| Sensor Data Integration | Time-series reaction data | Real-time yield prediction; Continuous monitoring | MAE of 1.2% for current yield; 4.6% for 120-min forecast [10] |

GNN Pre-training Workflow: This diagram illustrates the transfer learning process for graph neural networks in reaction yield prediction, from molecular database to fine-tuned model.

Reinforcement Learning for Reaction Mechanism Exploration and Optimization

Generalizable Frameworks for Catalytic Reaction Investigation

Reinforcement Learning (RL) has shown substantial potential for exploring complex catalytic reaction networks and mechanistic investigations [11]. Unlike traditional methods that might require enumerating all possible reaction pathways (leading to combinatorial explosion), RL employs an agent that learns to identify plausible reaction pathways through interactions with a defined environment over time [11].

The High-Throughput Deep Reinforcement Learning with First Principles (HDRL-FP) framework represents a significant advancement in this domain [11]. This reaction-agnostic approach defines the RL environment solely based on atomic positions, which are mapped to potential energy landscapes derived from first principles calculations. The framework implements several key innovations [11]:

- State Definition: States are represented by normalized Cartesian coordinates of atom positions and their Euclidean distances to target positions in the final product.

- Action Space: Actions are defined as stepwise movements of migrating atoms in six possible directions within a 3D grid.

- Reward System: A negative reward is assigned based on the electronic energy difference between states calculated from Density Functional Theory (DFT), with penalties for physically unrealistic atomic configurations.

A particularly powerful feature of HDRL-FP is its high-throughput capacity, enabling thousands of concurrent RL simulations on a single GPU [11]. This massive parallelism diversifies exploration across uncorrelated regions of the reaction landscape, dramatically improving training stability and reducing runtime. The framework has been successfully applied to investigate hydrogen and nitrogen migration in the Haber-Bosch ammonia synthesis process on Fe(111) surfaces, identifying reaction paths with lower energy barriers than those found through traditional nudged elastic band calculations [11].

Prioritizing General Applicability in Reaction Optimization

Reinforcement learning approaches are particularly valuable for identifying reaction conditions that demonstrate general applicability across diverse substrates - a highly desirable characteristic in synthetic chemistry [12]. Bandit optimization models, a class of RL algorithms, can efficiently discover such generally applicable conditions during optimizations de novo [12].

These approaches work by formulating reaction optimization as a sequential decision-making process where the RL agent [12] [11]:

- Selects Conditions: Chooses reaction conditions (e.g., catalysts, solvents, temperature) based on current policy.

- Receives Feedback: Obtains rewards based on reaction outcomes (e.g., yield, selectivity).

- Updates Policy: Adjusts its selection strategy to maximize cumulative rewards over time.

This framework has demonstrated both statistical accuracy in benchmarking studies and practical utility in experimental applications, including palladium-catalyzed imidazole C-H arylation and aniline amide coupling reactions [12]. By prioritizing general applicability, these RL models help identify robust reaction conditions that perform well across multiple substrate types, reducing the need for extensive re-optimization when applying synthetic methodologies to new molecular systems.

Table 2: Reinforcement Learning Applications in Reaction Optimization

| RL Approach | Application Scope | Key Innovation | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| HDRL-FP Framework | Catalytic reaction mechanisms | Reaction-agnostic representation; High-throughput on single GPU | Haber-Bosch process; Lower energy barriers identified [11] |

| Bandit Optimization Models | Generally applicable conditions | Prioritizes broad substrate applicability | Pd-catalyzed C-H arylation; Aniline amide coupling [12] |

| Traditional RL | Specific reaction networks | Depends on manual state encoding and reward design | Limited to predefined reaction sets [11] |

RL Reaction Exploration: This diagram shows the reinforcement learning cycle for catalytic reaction mechanism investigation, from state representation to policy update.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Transfer Learning for GNN-Based Yield Prediction

Objective: To predict chemical reaction yields using Graph Neural Networks with limited training data via transfer learning.

Materials:

- Molecular database (e.g., ZINC15, ChEMBL)

- Reaction dataset with yield values

- Mordred descriptor calculator

- GNN architecture (e.g., MPNN, Attentive FP)

Procedure:

- Pre-training Phase: a. Calculate 1,613 2D molecular descriptors for each molecule in the large-scale molecular database using the Mordred calculator [9]. b. Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce descriptor dimensionality while preserving >95% variance [9]. c. Train GNN to predict the PCA-reduced descriptor vectors from molecular graphs (pre-text task) for sufficient epochs until validation loss plateaus.

- Fine-tuning Phase: a. Initialize yield prediction model with weights from the pre-trained GNN. b. Represent chemical reactions as sets of reactant molecular graphs and product molecular graphs [9]. c. Train the model on reaction-yield pairs using mean absolute error or mean squared error loss function. d. Employ early stopping based on validation set performance to prevent overfitting.

Validation: Evaluate model performance on held-out test reactions using metrics such as Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and R² correlation coefficient.

Protocol: Active Learning for Reaction Space Exploration with Limited Data

Objective: To accurately predict yields across large reaction spaces while experimentally testing only a small fraction (2.5-5%) of possible combinations.

Materials:

- Defined reaction space with specified variables (catalysts, ligands, solvents, etc.)

- High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) equipment (optional but beneficial)

- Representation learning framework (e.g., neural network encoder)

Procedure:

- Initialization: a. Define the full reaction space encompassing all possible combinations of reaction components. b. Select an initial set of reaction combinations uniformly at random or based on prior knowledge [4].

Iterative Active Learning Cycle: a. Yield Evaluation: Conduct experiments for the selected reaction combinations and record yields [4]. b. Representation Learning: Update the model's representation of the reaction space using all accumulated yield data [4]. c. Data Selection: Apply the max coverage algorithm to select the next batch of reaction combinations that provide the most information gain [4]. d. Repeat steps a-c for 3-5 iterations or until model performance stabilizes.

Full Space Prediction: a. Use the final model trained on the selected reactions to predict yields for all combinations in the reaction space. b. Identify promising high-yield conditions for experimental verification.

Validation: Compare predicted versus actual yields for held-out test reactions. For the Buchwald-Hartwig coupling dataset, the method achieved >60% predictions with absolute errors <10% using only 5% of the total reaction space for training [4].

Protocol: Reinforcement Learning for Reaction Mechanism Investigation

Objective: To autonomously explore catalytic reaction paths and mechanisms using reinforcement learning.

Materials:

- DFT calculation software (e.g., VASP, Gaussian)

- Reinforcement learning framework with parallel computing capability

- GPU cluster for high-throughput simulations

Procedure:

- Environment Setup: a. Define state space using Cartesian coordinates of atom positions [11]. b. Define action space as discrete movements of atoms in six directions (forward, backward, up, down, left, right) [11]. c. Establish reward function based on energy differences from DFT calculations: ( r = -\Delta E / E_0 ) with penalty for unrealistic atomic proximity [11].

High-Throughput Training: a. Initialize policy network with random weights. b. Run thousands of parallel simulations on a single GPU to explore diverse reaction pathways [11]. c. At each step, agents select actions based on current policy, receive rewards from environment, and store experiences in replay memory. d. Periodically update policy network using sampled experiences from replay memory.

Pathway Analysis: a. After convergence, extract optimal reaction path with highest cumulative reward. b. Analyze identified mechanism and compare with known pathways from literature. c. Validate energetics and transition states through additional DFT calculations.

Validation: Apply to known systems (e.g., Haber-Bosch process) to verify the framework can rediscover established mechanisms with lower energy barriers [11].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for AI-Driven Reaction Optimization

| Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function/Purpose | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors | Mordred Calculator [9] | Generates 1,826 molecular descriptors per molecule | Pre-training GNNs; Molecular similarity analysis |

| Reaction Datasets | USPTO [13]; Buchwald-Hartwig [4]; Suzuki-Miyaura [4] | Provides reaction data for training and benchmarking | Model training; Transfer learning; Method validation |

| Neural Network Architectures | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [9]; Transformers [9] | Processes molecular graphs; Handles sequence data | Molecular representation; Yield prediction |

| Reinforcement Learning Frameworks | HDRL-FP [11]; Bandit Algorithms [12] | Explores reaction spaces; Optimizes conditions | Reaction mechanism investigation; Condition screening |

| Quantum Chemistry Tools | Density Functional Theory (DFT) [11] | Provides energy calculations for reward signals | RL environment; Reaction barrier validation |

| Active Learning Components | RS-Coreset [4]; Max Coverage Algorithm [4] | Selects most informative experiments | Data-efficient reaction space exploration |

The integration of AI techniques, particularly neural networks and reinforcement learning, is fundamentally transforming the landscape of reaction yield prediction and condition optimization in chemical research. These approaches enable a systematic, data-driven methodology for navigating complex reaction spaces that would be intractable through traditional empirical approaches alone. The synergistic combination of GNNs for molecular representation learning and RL for strategic exploration creates a powerful framework for accelerating chemical discovery.

As noted by the FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), regulatory agencies have observed a significant increase in drug application submissions incorporating AI components in recent years [14]. This trend underscores the growing importance and acceptance of these methodologies within the pharmaceutical industry. The establishment of dedicated oversight bodies, such as the CDER AI Council in 2024, further demonstrates the commitment to developing appropriate regulatory frameworks for AI-driven drug development [14].

Future advancements in this field will likely focus on enhancing model interpretability, developing more comprehensive and standardized reaction datasets, and creating integrated platforms that seamlessly combine computational predictions with experimental validation. As these AI techniques continue to mature and evolve, they hold immense potential to dramatically reduce the time and cost associated with chemical reaction optimization and drug development while promoting more sustainable laboratory practices through reduced experimental waste [8] [7]. The successful integration of biological sciences with algorithmic approaches will be crucial for realizing the full potential of AI-driven therapeutics in the pharmaceutical industry [15].

The application of machine learning (ML) to predict chemical reaction yields and optimize conditions represents a paradigm shift in organic chemistry and drug development. The accuracy and generalizability of these data-driven models are fundamentally dependent on the quality, scale, and diversity of the underlying chemical reaction databases. These databases provide the essential substrate from which models learn the complex relationships between reaction components, conditions, and outcomes. This Application Note delineates the critical databases available to researchers and provides detailed protocols for their use in building predictive ML models for reaction yield prediction.

The following tables summarize key large-scale and targeted high-throughput experimentation (HTE) databases that serve as the foundation for ML model development.

Table 1: Large-Scale Chemical Reaction Databases for Global Model Development. These databases provide broad coverage across diverse reaction types, enabling the training of globally applicable models.

| Database Name | Number of Reactions | Availability | Key Features and Use-Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaxys [16] | ~65 million | Proprietary | A vast proprietary database; used for training broad reaction condition recommender models. |

| Open Reaction Database (ORD) [17] [16] | ~1.7 million (from USPTO) + ~91k (community) | Open Access | An open-source initiative; aims to standardize and collect synthesis data; used for pre-training foundation models like ReactionT5. |

| SciFindern [16] | ~150 million | Proprietary | Extensive proprietary database of chemical reactions and substances. |

| Pistachio [16] | ~13 million | Proprietary | A large proprietary reaction database commonly used in ML for chemistry. |

| USPTO [6] | ~1.8 million (pre-2016) | Open Access | A large database of reactions from U.S. patents; often used as a benchmark for model pre-training. |

| Chemical Journals with High Impact Factor (CJHIF) [6] | >3.2 million | Open Access | Contains reactions extracted from chemistry journals; can be augmented with USPTO to balance yield distributions. |

Table 2: High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Datasets for Local Model Development. These focused datasets are ideal for optimizing specific reaction types and benchmarking optimization algorithms.

| Dataset Name | Reaction Type | Number of Reactions | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buchwald-Hartwig Coupling (1) | Pd-catalyzed C-N cross-coupling | 4,608 | Ahneman et al. (2018) [16] [18] |

| Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling (1) | C-C cross-coupling | 5,760 | Perera et al. (2018) [6] [16] |

| Buchwald-Hartwig Coupling (2) | Pd-catalyzed C-N cross-coupling | 288 | [16] |

| Electroreductive Coupling | Alkenyl and benzyl halides | 27 | [16] |

| C2-carboxylated 1,3-azoles | Amide-coupled carboxylation | 288 (264 used) | Felten et al. [18] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing a Two-Stage Pre-training Framework with ReaMVP

The Reaction Multi-View Pre-training (ReaMVP) framework leverages a two-stage pre-training strategy to enhance the generalization capability of yield prediction models by incorporating multiple views of chemical data [6].

I. Materials and Software

- Data Sources: USPTO database, CJHIF dataset.

- Software: RDKit (for molecule processing and 3D conformer generation), Python-based deep learning frameworks (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow).

- Computing: NVIDIA GPU (e.g., RTX A6000) for accelerated model training.

II. Procedure

- Data Preprocessing: a. Obtain the raw USPTO and CJHIF datasets. b. Remove duplicate records and invalid reactions that RDKit fails to recognize. c. Convert all remaining reactions into SMILES format. d. For 3D geometric information, generate one conformer for each molecule using the ETKDG algorithm within RDKit with default parameters. e. To address bias in yield distribution, augment the USPTO dataset with low-yield reactions (<50%) from the CJHIF dataset, creating a balanced pre-training dataset (e.g., USPTO-CJHIF).

First-Stage Pre-training (Sequential and Geometric Views): a. Model Input: Prepare reaction data as both sequential (SMILES strings) and geometric (3D conformers) views. b. Self-Supervised Learning: Train the model using distribution alignment and contrastive learning to capture the consistency between the sequential and geometric views of the same reaction. This step teaches the model to align the different representations without requiring yield labels.

Second-Stage Pre-training (Supervised Fine-tuning): a. Model Input: Use the same multi-view data (SMILES and 3D conformers) from the balanced USPTO-CJHIF dataset. b. Supervised Learning: Further train the model from the first stage using reactions with known yields. The objective is to minimize the difference between the predicted and actual yields, allowing the model to learn the specific relationship between reaction features and outcome.

Downstream Fine-tuning: a. Dataset: Apply the pre-trained ReaMVP model to a specific downstream yield prediction task, such as the Buchwald-Hartwig or Suzuki-Miyaura HTE dataset. b. Transfer Learning: Fine-tune the model on the smaller, targeted dataset. The model's pre-learned representations enable high performance even with limited task-specific data.

III. Analysis and Notes

- This protocol results in a model with superior generalization capability, particularly for out-of-sample predictions where test reactions contain molecules not seen during training [6].

- The multi-view approach allows the model to capture more comprehensive structural information than models based on a single data type.

Protocol: Yield Prediction and Optimization with Limited Data using RS-Coreset

For scenarios with limited experimental budget, the RS-Coreset method provides an active learning framework to efficiently explore a large reaction space and predict yields using only a small fraction of the possible combinations [4].

I. Materials and Software

- Data Source: A defined "reaction space" comprising all possible combinations of reactants, catalysts, ligands, bases, solvents, and other components.

- Software: Implementation of the RS-Coreset algorithm and a yield prediction model (e.g., Random Forest, Neural Network).

II. Procedure

- Reaction Space Definition: a. Predefine the scopes of all reaction components (e.g., 15 aryl halides, 4 ligands, 3 bases, 23 additives), which collectively form the reaction space (e.g., 15 x 4 x 3 x 23 = 3,955 combinations).

Initial Sampling: a. Select an initial small set of reaction combinations (e.g., 1-2% of the space) uniformly at random or based on prior literature knowledge.

Iterative Active Learning Loop: a. Yield Evaluation: Perform laboratory experiments on the selected reaction combinations and record their yields. b. Representation Learning: Update the machine learning model's representation of the reaction space using the newly acquired yield data. This step refines the model's understanding of how molecular features and conditions correlate with yield. c. Data Selection (Coreset Construction): Using a maximum coverage algorithm, select the next set of reaction combinations that are most informative for the model. These are typically points where the model is most uncertain or that best represent the diversity of the unexplored space. d. Repeat steps a-c for a fixed number of iterations or until the model's predictions stabilize.

Full-Space Prediction: a. After the final iteration, use the trained model to predict the yields for all remaining untested combinations in the reaction space.

III. Analysis and Notes

- This method has been validated to achieve promising prediction accuracy (e.g., over 60% of predictions with absolute errors less than 10%) while requiring experimental yields for only 5% of the total reaction space [4].

- It effectively discovers high-yielding reaction conditions that might be overlooked by traditional approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Reagents for Yield Prediction Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role in Research | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit; used for calculating molecular descriptors, processing SMILES, and generating 3D conformers. | rdkit.Chem.Descriptors module (209 descriptors); ETKDG conformer generation [6] [18]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) | Technology to run numerous reactions in parallel; generates large, standardized datasets crucial for training local ML models. | 1536-well plates for Buchwald-Hartwig reactions [6]. |

| SentencePiece Unigram Tokenizer | Converts SMILES strings into subword tokens for transformer-based models; more efficient than character-level tokenization. | Used in pre-training models like ReactionT5 [17]. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) | An iterative optimization algorithm used to efficiently navigate reaction condition search spaces and maximize yield. | Often used with a Graph Neural Network (GNN) surrogate model for reaction condition optimization [19]. |

| SHAP / PIXIE | Model interpretation tools; quantify and visualize the importance of specific molecular substructures on the predicted yield. | PIXIE generates heat maps based on fingerprint bit importance [18]. |

| 4-Bromo-3,3-dimethylbutanoic acid | 4-Bromo-3,3-dimethylbutanoic Acid|C6H11BrO2 | 4-Bromo-3,3-dimethylbutanoic acid (C6H11BrO2) is a high-purity building block for organic synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Benzyldodecyldimethylammonium Chloride Dihydrate | Benzyldodecyldimethylammonium Chloride Dihydrate, MF:C21H42ClNO2, MW:376.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the integrated workflow for developing machine learning models for yield prediction, from data sourcing to final application.

Figure 1: ML for Yield Prediction Workflow.

The advancement of machine learning in chemical reaction prediction is intrinsically linked to the development and intelligent utilization of chemical reaction databases. As demonstrated by the protocols and data herein, the strategic combination of large-scale general databases and focused HTE datasets enables the creation of models that range from broadly applicable to highly specialized. The ongoing community efforts to create open-access, standardized databases like the ORD are crucial for fostering innovation and ensuring that the benefits of data-driven discovery are widely accessible. By adhering to the detailed protocols for pre-training and active learning outlined in this document, researchers can effectively leverage these data foundations to accelerate the development of new pharmaceuticals and materials.

AI in Action: Key Algorithms and Models for Yield Prediction and Synthesis Planning

Retrosynthetic Analysis Automation with Transformer Models and GNNs

Retrosynthetic analysis is a fundamental process in organic chemistry and drug discovery, involving the deconstruction of a target molecule into progressively simpler precursors to identify viable synthetic routes [20]. The automation of this process using artificial intelligence is revolutionizing the field, accelerating research in digital laboratories while reducing costs and experimental failures [21] [20].

Traditional computational approaches faced significant limitations, including reliance on manually encoded reaction templates and inability to predict novel chemistry [22]. The advent of deep learning, particularly Transformer architectures and Graph Neural Networks, has enabled template-free prediction that learns directly from reaction data, capturing complex chemical patterns without predefined rules [20] [23].

This application note explores the integration of Transformer models and GNNs for retrosynthetic analysis, providing detailed protocols and performance comparisons to guide researchers in implementing these advanced computational techniques within drug development pipelines.

Molecular Representation for Machine Learning

Chemical structures can be represented in multiple formats for computational analysis:

- SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System): A linear string notation that serializes molecular structures [23]. While convenient for sequence-based models, SMILES representations can lose spatial structural information and sometimes generate invalid syntax [20].

- Molecular Graphs: Represent atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, preserving the topological structure of molecules [20] [22]. This representation is more naturally processed by GNNs and captures essential structural relationships.

- Reaction SMILES: Extends SMILES to represent complete chemical reactions, including reactants, reagents, and products in a single string [24].

Model Architectures

Transformer Models

Transformers utilize a self-attention mechanism to capture global dependencies in sequence data, making them particularly suitable for chemical reaction prediction and retrosynthesis planning [23]. The self-attention mechanism dynamically weights the importance of different atoms and functional groups within a molecular sequence, enabling the model to identify key reaction sites [23].

Recent innovations include RetroExplainer, which formulates retrosynthesis as a molecular assembly process with interpretable decision-making [20], and ReactionT5, a text-to-text transformer model pre-trained on extensive reaction databases that achieves state-of-the-art performance across multiple tasks [24].

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)

GNNs operate directly on graph-structured data, making them ideal for processing molecular graphs [21] [22]. Through iterative message passing between connected nodes, GNNs learn representations that capture both atomic properties and molecular topology.

Frameworks like GraphRXN utilize communicative message passing neural networks to generate comprehensive reaction embeddings from molecular graphs, enabling accurate reaction outcome prediction [22]. GNNs are particularly valuable for identifying reaction centers and completing synthons in template-free retrosynthesis approaches [20].

Hybrid Architectures

Emerging approaches combine the strengths of both architectures. RetroExplainer incorporates a Multi-Sense and Multi-Scale Graph Transformer (MSMS-GT) that captures both local molecular structures and long-range chemical interactions [20]. Similarly, Graphormer integrates graph representations with transformer-style attention to model multi-scale topological relationships in molecules [20].

Performance Analysis

Model Benchmarking on Standard Datasets

Table 1: Performance comparison of retrosynthesis models on USPTO-50K dataset

| Model | Approach | Top-1 Accuracy (%) | Top-3 Accuracy (%) | Top-5 Accuracy (%) | Top-10 Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RetroExplainer | Graph Transformer + Molecular Assembly | 56.5 | 73.8 | 80.1 | 85.2 |

| ReactionT5 | Pre-trained Transformer | 71.0* | - | - | - |

| G2G | Graph-to-Graph (GNN) | 48.9 | - | - | - |

| GraphRetro | MPNN-based | 53.7 | - | - | - |

| LocalRetro | GNN + Local Attention | 56.3 | 74.1 | 80.7 | 86.2 |

| Transformer | Sequence-based | 46.9 | 65.3 | 72.4 | 79.4 |

Note: Performance metrics vary based on evaluation settings; ReactionT5 top-1 accuracy reported for retrosynthesis task [24]; RetroExplainer metrics represent averaged performance under known and unknown reaction type conditions [20].

Multi-Step Synthesis Planning

For complete synthetic route planning, retrosynthesis models integrate with search algorithms. Recent evaluation of RetroExplainer integrated with the Retro* algorithm demonstrated that the system identified 101 pathways for complex drug molecules, with 86.9% of the single reactions corresponding to literature-reported reactions [20].

Advanced systems now employ group retrosynthesis planning that identifies reusable synthesis patterns across similar molecules, significantly reducing inference time for AI-generated compound libraries [25]. This approach mimics human learning by abstracting common multi-step reaction processes (cascade and complementary reactions) and building an evolving knowledge base [25].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing RetroExplainer for Interpretable Retrosynthesis

Purpose: To perform single-step retrosynthesis prediction with interpretable decision-making using the RetroExplainer framework.

Materials and Inputs:

- Target molecule in SMILES format

- Pre-trained RetroExplainer model [20]

- USPTO-50K or similar reaction dataset for training/validation

- Hardware: NVIDIA GPU with ≥8GB VRAM

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Convert SMILES to molecular graph representation with atom and bond features

- Apply reaction class annotation if available

- Split data using Tanimoto similarity threshold (0.4-0.6) to prevent scaffold bias [20]

Model Configuration:

- Implement Multi-Sense Multi-Scale Graph Transformer (MSMS-GT) with structure-aware contrastive learning

- Configure dynamic adaptive multi-task learning (DAMT) for balanced optimization

- Set molecular assembly parameters: energy thresholds, step limitations

Training:

- Initialize with pre-trained weights if available

- Train for 100 epochs with early stopping

- Use Adam optimizer with learning rate 0.001

- Apply gradient clipping at norm 1.0

Interpretation:

- Generate energy decision curve for prediction steps

- Extract substructure-level attribution scores

- Visualize counterfactual predictions to identify potential biases

Validation: Compare top-10 accuracy against USPTO-50K test set; expected performance: >85% top-10 accuracy [20]

Protocol 2: ReactionT5 for Multi-Task Chemical Prediction

Purpose: To utilize a pre-trained transformer model for product prediction, retrosynthesis, and yield prediction.

Materials and Inputs:

- ReactionT5 pre-trained model [24]

- Open Reaction Database (ORD) or proprietary reaction data

- Text-to-text framework for sequence generation

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Format reactions with role-specific tokens (REACTANT:, REAGENT:, PRODUCT:)

- Concatenate multiple compounds in same role with "." separator

- For yield prediction, include numerical values normalized to 0-1 range

Model Fine-tuning:

- Load ReactionT5 base architecture

- For limited data scenarios (<10,000 reactions), use reduced learning rate (0.0001)

- Employ span-masked language modeling objective for 15% of tokens

- Train with Adafactor optimizer, batch size 32 for 50 epochs

Multi-Task Implementation:

- Product Prediction: Input reactants and reagents, generate products

- Retrosynthesis: Input products, generate reactant sequences

- Yield Prediction: Input full reaction context, generate normalized yield

Evaluation:

- Assess product prediction accuracy on benchmark datasets

- Calculate exact match accuracy for retrosynthesis proposals

- Measure R² value for yield prediction tasks

Validation Metrics: Expected performance: 97.5% product prediction accuracy, 71.0% retrosynthesis accuracy, R² = 0.947 for yield prediction [24]

Protocol 3: Group Retrosynthesis Planning for Similar Molecules

Purpose: To efficiently plan synthetic routes for groups of structurally similar molecules by identifying reusable reaction patterns.

Materials and Inputs:

- Set of structurally similar target molecules (e.g., from generative AI output)

- Existing reaction template library

- Purchasable building block database

Procedure:

- Wake Phase:

- Construct AND-OR search graph for initial molecule

- Use neural network models to guide graph expansion

- Record successful synthesis routes and failure patterns

Abstraction Phase:

- Extract cascade reaction chains (consecutive transformations)

- Identify complementary reaction relationships (precursor interactions)

- Define abstract reaction templates from successful patterns

Dreaming Phase:

- Generate synthetic retrosynthesis data ("fantasies")

- Refine neural models using combined real and synthetic data

- Practice application of new abstract templates

Group Application:

- Apply evolved template library to similar molecules

- Reuse identified reaction patterns where applicable

- Continuously update library with new discoveries

Validation: Measure reduction in inference time across molecule group; expected outcome: progressively decreasing marginal inference time with each additional molecule [25]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential computational tools and databases for retrosynthetic analysis

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| USPTO-50K | Dataset | 50,000 experimental reactions for model training and benchmarking | Public [20] |

| Open Reaction Database (ORD) | Dataset | Large-scale, open-access reaction database with condition details | Public [24] [16] |

| Reaxys | Database | Millions of reactions for training global prediction models | Proprietary [26] [16] |

| RetroExplainer | Software Framework | Interpretable retrosynthesis via molecular assembly | Research Implementation [20] |

| ReactionT5 | Pre-trained Model | Transformer-based foundation model for multiple reaction tasks | Research Implementation [24] |

| GraphRXN | GNN Framework | Message passing neural network for reaction prediction | Research Implementation [22] |

| SciFindern | Database | Literature reaction search for experimental validation | Proprietary [20] |

Implementation Considerations

Data Quality and Availability

The performance of retrosynthesis models heavily depends on training data quality and diversity. Common challenges include:

- Publication Bias: Commercial databases often extract only successful conditions, lacking failed experiments that are crucial for robust model generalization [16]

- Standardization Issues: Yield measurements may use different methodologies (crude yield, isolated yield, NMR, LC area percentage) across data sources [16]

- Reaction Representation: Accurate condition prediction requires distinguishing between catalysts, reagents, and solvents, which are often mislabeled in datasets [24]

Model Selection Guidelines

- For Interpretable Prediction: Choose RetroExplainer when transparency in decision-making is crucial [20]

- For Multi-Task Applications: ReactionT5 is optimal when product prediction, retrosynthesis, and yield prediction are all required [24]

- For Limited Data Scenarios: Fine-tuned pre-trained models (e.g., ReactionT5) maintain performance with limited task-specific data [24]

- For Similar Molecule Groups: Implement group retrosynthesis planning to leverage reusable synthetic patterns [25]

Transformer models and GNNs have significantly advanced the automation of retrosynthetic analysis, enabling accurate prediction of synthetic pathways for complex drug molecules. The integration of these technologies with experimental validation creates a powerful framework for accelerating drug discovery and development. As these models continue to evolve—incorporating better interpretability, handling broader reaction spaces, and learning from fewer examples—they promise to further reduce the time and cost associated with synthetic planning while increasing overall success rates.

Within the broader context of machine learning for predicting reaction yields and conditions, the task of reaction outcome prediction stands as a fundamental challenge in organic synthesis. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, accurately forecasting the products or yield of a chemical reaction prior to wet-lab experimentation can dramatically accelerate discovery timelines and conserve valuable resources [27]. This application note details the integration of supervised learning and deep neural networks (DNNs) to address this challenge, providing structured protocols, data comparisons, and essential toolkits for practical implementation. The move from traditional, descriptor-based models to modern deep learning frameworks that learn directly from molecular structure represents a significant shift in the field, enabling the modeling of more complex chemical relationships and the exploration of broader reaction spaces [27] [22].

Machine Learning Approaches for Reaction Prediction

Deep Kernel Learning (DKL) for Uncertainty-Aware Prediction

Deep Kernel Learning (DKL) represents a hybrid approach that merges the strengths of neural networks and Gaussian Processes (GPs). This framework utilizes a neural network to learn optimal feature representations directly from raw molecular inputs, such as fingerprints or graphs. These features are then fed into a Gaussian Process, which provides the final prediction along with a reliable uncertainty estimate [27]. This uncertainty quantification is critical for applications like Bayesian optimization, where it guides the exploration of chemical space by balancing the testing of high-risk, high-reward conditions against the refinement of known promising areas [27] [28].

- Key Architecture: The model typically consists of a feature extraction front-end (e.g., a fully connected network for fingerprints or a Graph Neural Network for molecular graphs) followed by a GP posterior computation back-end.

- Advantages: It achieves predictive performance comparable to state-of-the-art graph neural networks while providing essential uncertainty estimates, a feature often lacking in pure deep learning models. It is also flexible, working effectively with both learned and non-learned molecular representations [27].

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for Structure-Based Prediction

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have become a dominant architecture for reaction prediction because they natively operate on molecular graphs, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges. Models like the GraphRXN framework use a message-passing neural network to learn meaningful representations of reactants and reagents [22]. In this process, node (atom) and edge (bond) features are iteratively updated by aggregating information from their local environments. A readout function then generates a fixed-dimensional embedding for the entire molecule or reaction, which is used for final prediction tasks such as yield regression [27] [22].

- Key Architecture: The framework involves message passing, information updating, and a readout step (e.g., using a Gated Recurrent Unit or set2set model) to create a graph-level embedding. The embeddings of individual reaction components are often summed or concatenated to form a final reaction representation [27] [22].

- Advantages: GNNs automatically learn task-relevant features directly from the molecular structure, eliminating the need for manual feature engineering and its inherent biases [22].

Chemical Reaction Neural Networks (CRNNs) for Interpretable Kinetics

Chemical Reaction Neural Networks (CRNNs) offer a physically grounded approach by embedding known chemical laws, such as the law of mass action and the Arrhenius equation, directly into the network's architecture [29] [30]. This ensures that the model's predictions are not only accurate but also interpretable and consistent with physical principles. Recent advancements include Kolmogorov-Arnold CRNNs (KA-CRNNs), which extend this framework to model pressure-dependent kinetics by representing kinetic parameters as learnable functions of system pressure [29]. Furthermore, Bayesian extensions to CRNNs enable autonomous quantification of uncertainty in the inferred kinetic parameters [30].

- Key Architecture: A CRNN structures its layers and activations to directly represent the logarithmic form of the Arrhenius and mass action laws. KA-CRNNs incorporate univariate Kolmogorov-Arnold Network (KAN) activations to model how kinetic parameters like activation energy change with external variables like pressure [29].

- Advantages: CRNNs provide high interpretability and generate compact, physically meaningful models. They are particularly valuable for inferring reaction mechanisms and kinetics from time-series data [29] [30].

Data Augmentation and Transfer Learning for Low-Data Regimes

A significant hurdle in applying deep learning to chemistry is the scarcity of high-quality, large-scale reaction data for specific reaction types. To address this, virtual data augmentation and transfer learning have proven effective. Virtual data augmentation involves programmatically expanding a dataset by, for example, replacing functional groups in reactants with similar ones (e.g., chlorine with bromine) that do not alter the fundamental reaction chemistry but increase the diversity of training examples [31]. When combined with transfer learning—where a model is first pre-trained on a large, general reaction dataset (e.g., USPTO with over 1.9 million reactions) and then fine-tuned on a smaller, specific dataset—this strategy can lead to substantial improvements in prediction accuracy for specialized tasks [31] [32].

- Implementation: Augmentation is typically applied only to the training set. Transfer learning uses a large source dataset like USPTO-410k for pre-training before fine-tuning on the target reaction data [31].

- Advantages: These techniques mitigate overfitting in low-data scenarios, significantly boosting model performance and generalizability for under-represented reaction classes [31].

Table 1: Summary of Key Machine Learning Models for Reaction Outcome Prediction

| Model | Key Input Representation | Primary Output | Key Advantages | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Kernel Learning (DKL) [27] | Molecular fingerprints (e.g., DRFP), descriptors, or graphs | Reaction yield with uncertainty | Combines high accuracy with reliable uncertainty quantification; versatile input handling | Bayesian optimization of reaction conditions [27] |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [27] [22] | Molecular graphs (atoms, bonds) | Reaction yield or product | Learns features directly from molecular structure; no manual descriptor needed | GraphRXN model for yield prediction on HTE data [22] |

| Chemical Reaction Neural Networks (CRNNs) [29] [30] | Concentration time-series data | Kinetic parameters & reaction rates | Physically interpretable; embeds mass action & Arrhenius laws | Inference of pressure-dependent kinetics [29] |

| Transformer Models [31] | SMILES strings of reactants | SMILES string of major product | Template-free; treats reaction as a translation task | Predicting products for coupling reactions [31] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a DKL Model for Yield Prediction

This protocol outlines the steps for constructing a Deep Kernel Learning model to predict reaction yield with uncertainty, using the Buchwald-Hartwig amination reaction as an example [27].

Data Preparation:

- Input Representation: Choose and compute an input representation for the reaction. Options include:

- Differential Reaction Fingerprint (DRFP): A 2048-bit binary fingerprint generated from reaction SMILES [27].

- Morgan Fingerprints: Concatenated 512-bit fingerprints (radius 2) for each reactant, resulting in a 2048-dimensional vector [27].

- Molecular Descriptors: Concatenate DFT-computed electronic and spatial descriptors for all reactants [27].

- Data Splitting: Randomly split the dataset into training (70%), validation (10%), and test (20%) sets. Standardize the yield values based on the training set's mean and variance [27].

- Input Representation: Choose and compute an input representation for the reaction. Options include:

Model Construction:

- Feature Learning Network: For non-learned representations (fingerprints, descriptors), implement a feed-forward neural network with two fully connected layers. For learned representations (graphs), use a Graph Neural Network with message passing and a set2set readout layer to generate the reaction embedding [27].

- Gaussian Process Layer: Connect the output of the feature network to a GP with a base kernel (e.g., RBF). The input to this kernel is the embedding vector produced by the neural network [27].

Model Training:

- Objective Function: Train the entire model end-to-end by jointly optimizing the NN parameters and GP hyperparameters. The objective is to maximize the log marginal likelihood of the GP [27].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Use the validation set to tune hyperparameters such as learning rate, network architecture, and kernel parameters.

Prediction and Evaluation:

- Inference: For a test point, compute the posterior predictive distribution of the GP. The mean of this distribution is the predicted yield, and the variance represents the uncertainty [27].

- Evaluation: Assess model performance on the held-out test set using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) or R², averaged over multiple random splits [27].

Protocol 2: Implementing Virtual Data Augmentation

This protocol describes a method to augment a small reaction dataset to improve the performance of a deep learning model [31].

Data Collection and Curation:

- Export a specific reaction dataset (e.g., Suzuki coupling) from a database like Reaxys.

- Preprocess the data: canonicalize SMILES, remove duplicates, and filter reactions using template screening to ensure consistency [31].

Virtual Augmentation Strategy:

- Identify Replaceable Groups: Determine functional groups in the reactants that can be substituted without altering the core reaction mechanism. For cross-couplings, halogens (Cl, Br, I) are typical candidates [31].

- Generate Fake Data: Create new reaction entries by systematically replacing these groups with chemically similar alternatives (e.g., replacing chlorine with bromine or iodine). Ensure the replacements are valence-aware and do not modify the reaction center [31].

- Single vs. Simultaneous Augmentation:

- Single Augmentation: Replace functional groups in only one type of reactant.

- Simultaneous Augmentation: Replace groups in multiple reactants at once (e.g., halogens in aryl halides and boron groups in boronic acids for Suzuki reactions) [31].

Dataset Construction:

- Augment only the training dataset. Remove any duplicates that result from the augmentation process.

- Keep the validation and test sets unaugmented to ensure a fair evaluation of model generalizability to real, unseen data [31].

- The augmented dataset can be 2 to 6 times larger than the original raw data [31].

Model Training with Augmented Data:

- Train a sequence-based (e.g., Molecular Transformer) or graph-based model on the augmented training set.

- For best results, combine augmentation with transfer learning by first pre-training the model on a large public dataset like USPTO [31].

Table 2: High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Datasets for Model Training and Benchmarking

| Dataset Name | Reaction Type | Key Condition Variables | Number of Reactions | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buchwald-Hartwig HTE [27] [22] | Buchwald-Hartwig Amination | Aryl halide, ligand, base, additive | 3,955+ | Yield prediction, optimization |

| USPTO [33] [32] | Various organic reactions | General reaction SMILES | 1,939,253 (full) | Product prediction, pre-training |

| Mech-USPTO-31K [33] | Polar organic reactions (with mechanisms) | Reaction templates, mechanistic steps | ~31,000 | Mechanistic-based prediction |

| Ni-Suzuki HTE [28] | Nickel-catalysed Suzuki coupling | Precatalyst, ligand, base, solvent | 1,632 (from study) | Multi-objective Bayesian optimization |

Workflow Diagram: Integrated ML-Driven Reaction Optimization

The diagram below illustrates a closed-loop workflow for machine learning-guided reaction optimization, combining high-throughput experimentation with Bayesian optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Reaxys Database [31] [34] | A curated database of millions of chemical reactions, used for data mining and model training. | Source for extracting initial reaction datasets for specific named reactions (e.g., Suzuki, Buchwald-Hartwig) [31]. |

| RDKit [27] [31] | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit for working with molecular data and computing descriptors. | Calculating Morgan fingerprints, processing SMILES strings, extracting molecular graphs with atom/bond features [27]. |

| Differential Reaction Fingerprint (DRFP) [27] | A binary fingerprint for an entire reaction, generated from reaction SMILES via hashing and folding. | Input representation for DKL and other ML models that require a fixed-length reaction descriptor [27]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Platform [28] [22] | Automated robotic systems for performing numerous miniaturized reactions in parallel (e.g., in 96-well plates). | Generating high-quality, consistent datasets for model training and validating ML-proposed conditions in optimization loops [28]. |

| USPTO Dataset [33] [31] [32] | A large-scale dataset of reactions extracted from US patents, often used for pre-training. | Source of over 1.9 million general reactions for transfer learning to improve performance on specific, smaller datasets [31] [32]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Framework (e.g., Minerva) [28] | A software framework for multi-objective Bayesian optimization, handling large batch sizes. | Guiding the selection of the next batch of experiments in an HTE campaign by balancing exploration and exploitation [28]. |

| Oosporein | Oosporein, CAS:475-54-7, MF:C14H10O8, MW:306.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SLLK, Control Peptide for TSP1 Inhibitor(TFA) | SLLK, Control Peptide for TSP1 Inhibitor(TFA), MF:C23H42F3N5O8, MW:573.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Diagram: Graph Neural Network for Reaction Prediction

The diagram below details the architecture of a Graph Neural Network model (e.g., GraphRXN) for predicting reaction outcomes from molecular structures.

Optimizing Conditions with Bayesian Optimization and Active Learning

In the field of chemical and pharmaceutical research, optimizing reaction conditions and predicting yields are fundamental yet challenging tasks. The high-dimensional nature of chemical spaces, coupled with the cost and time of experimental work, makes traditional trial-and-error methods inefficient. Machine learning (ML) offers powerful solutions, with Bayesian Optimization (BO) and Active Learning (AL) emerging as particularly effective strategies for navigating complex experimental landscapes with limited data. Bayesian Optimization is a sample-efficient global optimization strategy for black-box functions that are expensive to evaluate, making it ideal for guiding experimental campaigns where each data point is costly [35] [36]. It operates by building a probabilistic surrogate model of the objective function (such as reaction yield) and uses an acquisition function to intelligently select the next experiments by balancing exploration of uncertain regions and exploitation of known promising areas [35]. Active Learning is a complementary machine learning paradigm that reduces data dependency by iteratively selecting the most informative data points to be labeled (i.e., experimentally measured), thereby building a robust model with minimal experiments [4] [37]. When framed within a broader thesis on machine learning for predicting reaction yields, these methods represent a paradigm shift from traditional, resource-intensive optimization towards intelligent, data-efficient experimental planning.

Application Notes: Key Use Cases in Chemical Synthesis

The integration of BO and AL has led to significant advancements across various domains of chemical synthesis, from reaction condition optimization to catalyst and molecule design. The following table summarizes key applications and their outcomes.

Table 1: Applications of Bayesian Optimization and Active Learning in Chemical Synthesis

| Application Area | Specific Use Case | Key Outcome | Quantitative Improvement | Citation |