Implementing FAIR Data Principles in Chemical Research: A Practical Guide for Enhanced Discovery and Collaboration

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for implementing FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data management principles in chemical research.

Implementing FAIR Data Principles in Chemical Research: A Practical Guide for Enhanced Discovery and Collaboration

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for implementing FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data management principles in chemical research. Covering foundational concepts, practical methodologies, optimization strategies, and validation techniques, it addresses critical challenges in chemical data sharing, regulatory compliance, and cross-disciplinary collaboration. Drawing on the latest guidelines from OECD, IUPAC, and global initiatives like WorldFAIR and NFDI4Chem, the guide offers actionable insights for improving data reproducibility, leveraging AI/ML in cheminformatics, and building sustainable data infrastructures that support innovation in biomedical and clinical research.

Understanding FAIR Chemistry: Why Data Principles Matter in Modern Research

For researchers in chemistry and drug development, managing complex data from experiments, simulations, and compound analysis presents significant challenges. The FAIR Guiding Principles—making data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable—provide a framework to enhance data management and stewardship [1] [2]. These principles emphasize machine-actionability, enabling computational systems to find, access, interoperate, and reuse data with minimal human intervention, which is crucial for handling the volume and complexity of modern research data [3] [4]. Implementing FAIR practices accelerates drug discovery, improves research reproducibility, and maximizes return on data investments by ensuring valuable data remains discoverable and usable throughout its lifecycle [3].

FAIR Principles Troubleshooting Guide

Findable

| Principle & Requirement | Common Experimental Issues | Troubleshooting Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| F1: Assign persistent identifiers [2] | Dataset cannot be reliably located or cited in future studies | Register data in a repository that provides DOIs (Digital Object Identifiers) or other persistent identifiers [5] [2] |

| F2: Describe with rich metadata [2] | Insufficient information for others to understand the dataset's content or context | Create comprehensive metadata using domain-specific schemas; avoid generic descriptions [5] [4] |

| F4: Index in a searchable resource [1] | Data is stored in personal or institutional storage, making discovery difficult | Deposit data in a recognized, indexed repository rather than in supplementary materials or upon request [5] |

Accessible

| Principle & Requirement | Common Experimental Issues | Troubleshooting Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| A1: Retrievable via standard protocol [2] | Data is stored in a proprietary system or requires special software to access | Use standard, open communication protocols (e.g., HTTPS) and ensure metadata is accessible even if data is restricted [6] [2] |

| A1.2: Authentication & authorization allowed [2] | Access restrictions are unclear, leading to failed access requests for sensitive data | Clearly document access conditions and procedures for restricted data, including how to request access [1] [3] |

| A2: Metadata remains accessible [2] | When data is removed or becomes unavailable, its historical record is lost | Ensure metadata is preserved in a trusted repository independently of the data's availability [6] [2] |

Interoperable

| Principle & Requirement | Common Experimental Issues | Troubleshooting Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| I1: Use formal knowledge language [2] | Data from different labs or instruments cannot be integrated or compared | Use open, standard file formats (e.g., CSV, XML, JSON) instead of proprietary formats [3] [2] |

| I2: Use FAIR vocabularies [2] | Semantic mismatches (e.g., different gene or compound names) hinder analysis | Describe data with controlled vocabularies and ontologies (e.g., InChI keys for chemical structures) [3] [7] |

| I3: Include qualified references [2] | Relationships between datasets (e.g., a sample and its analysis) are lost | Include qualified references to related (meta)data, such as linking a virtual sample to its physical archive [2] [7] |

Reusable

| Principle & Requirement | Common Experimental Issues | Troubleshooting Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| R1.1: Clear usage license [2] | License terms are ambiguous, preventing legitimate reuse due to legal concerns | Apply a clear, accessible data usage license (e.g., Creative Commons) at the time of publication [3] [4] |

| R1.2: Detailed provenance [2] | The methods and steps used to create the data are unclear, preventing replication | Document detailed provenance describing how data was generated, processed, and transformed [3] [2] |

| R1.3: Meet community standards [2] | Data does not comply with field-specific requirements, limiting its acceptance | Follow domain-relevant community standards for data and metadata [2] [4] ``` |

Essential Tools & Workflows for FAIR Chemical Data

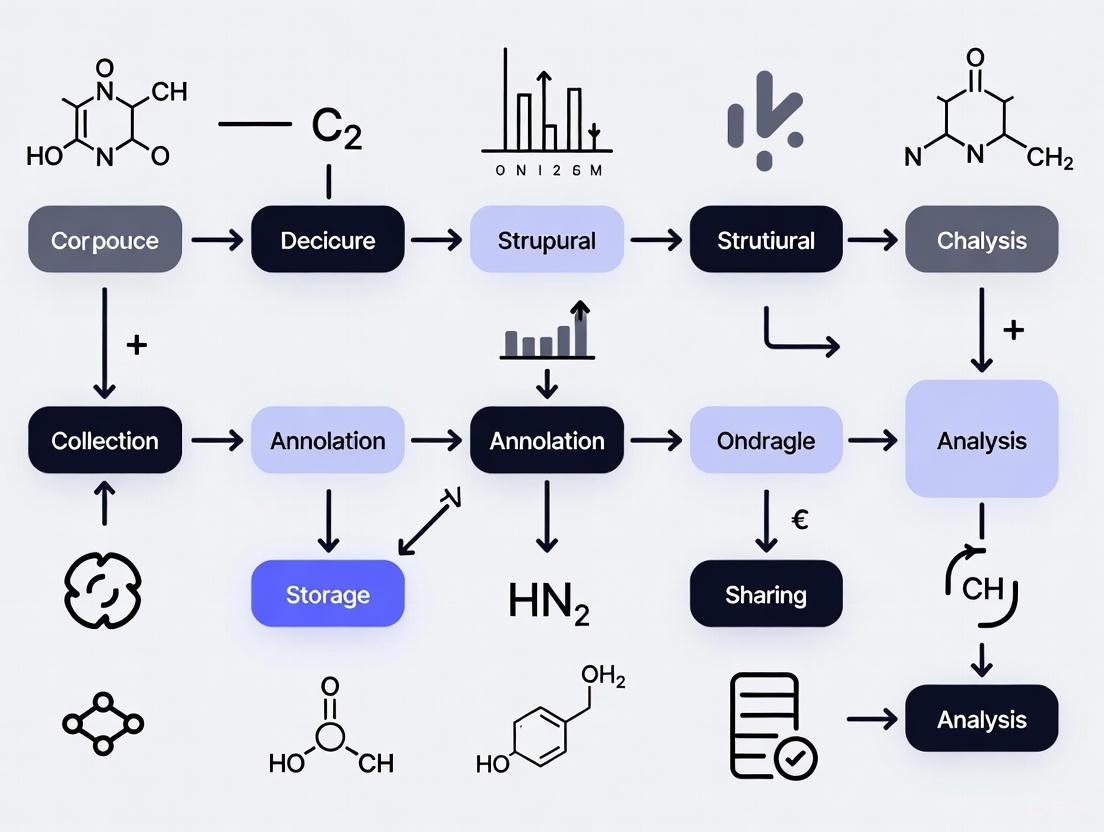

This workflow for managing chemical research data and materials integrates the FAIR principles for digital objects with the physical preservation of samples.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in FAIR Implementation |

|---|---|

| Trusted Repository (e.g., FigShare, Dataverse, Chemotion) | Provides persistent identifiers (DOIs), standard access protocols, and long-term preservation for data [2] [7] |

| Metadata Schema (e.g., ISA, Dublin Core) | Defines a structured set of field names and descriptions to ensure consistent and complete data annotation [5] |

| Controlled Vocabularies/Ontologies (e.g., InChI, ChEBI) | Provides standardized, machine-readable terms for describing data, enabling semantic interoperability [3] [7] |

| Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) | Captures experimental context, parameters, and procedures at the source, facilitating rich provenance documentation [7] |

FAQs on FAIR Implementation

Q1: Are FAIR data and Open data the same thing? No. Open data focuses on making data freely available to everyone without restrictions. FAIR data focuses on the structure, description, and machine-actionability of data, which can be either openly available or restricted with proper access controls [3]. FAIR data does not necessarily have to be open.

Q2: What is the most common barrier to making data FAIR? A significant barrier is the lack of tangible incentives for researchers. Documenting data to make it reusable requires substantial time and effort, which is often not recognized in grant reviews or academic promotions [5]. Solutions include dedicated funding for data management and tracking data sharing compliance as a positive factor in evaluations [5].

Q3: How can I make my legacy data FAIR? Making legacy data FAIR can be challenging and costly [3]. Key steps include: (1) migrating data to open, standard file formats, (2) retroactively creating rich metadata and documentation (e.g., README files), and (3) depositing the curated dataset into a trusted repository that assigns a persistent identifier [2].

Q4: How do I handle physical samples (chemical compounds) under FAIR? The FAIR-FAR concept extends the principles to physical materials. A virtual sample representation with rich, FAIR metadata and a DOI is created in a data repository. This digital record is then linked to the physically preserved sample in a materials archive, making the sample itself findable, accessible, and reusable [7].

Q5: How is FAIR compliance measured? Compliance is assessed using various FAIR assessment tools (e.g., F-UJI, FAIR-Checker) which automatically or manually evaluate datasets against specific metrics for each principle [6] [8]. Be aware that different tools may produce varying scores due to different metric implementations [8].

The Critical Need for FAIR Data in Chemical Sciences and Drug Development

FAIR Data Principles: Core Concepts

What are the FAIR Data Principles?

The FAIR Guiding Principles are a set of guidelines for enhancing the reusability of scholarly data and other digital research objects. First formally published in 2016, FAIR stands for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable [9]. These principles provide a systematic framework for managing research data, with special emphasis on enabling both humans and machines to discover, access, integrate, and analyze data with minimal intervention [1] [9].

Why are FAIR Principles Critical for Chemical Sciences and Drug Development?

The chemical sciences are generating unprecedented volumes of complex data from increasingly sophisticated and automated tools [10]. Implementing FAIR principles addresses several critical needs:

- Improved Research Efficiency: Approximately 80% of all effort regarding data goes into data wrangling and preparation, while only 20% constitutes actual research and analytics, primarily because data aren't yet FAIR [10].

- Enhanced Reproducibility: Well-documented data allows others to validate findings, which is particularly crucial in drug development where reproducibility crises can cost millions [10] [11].

- Accelerated Discovery: During the COVID-19 pandemic, the availability of virus, patient, and therapeutic discovery data in FAIR format could have accelerated response efforts by enabling large-scale analysis [11].

- Regulatory and Funder Compliance: Major funding agencies like the European Research Council and NIH now mandate FAIR-aligned data management plans for funded research [10].

FAIR Data Troubleshooting Guide

Common FAIR Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Table: FAIRification Challenges and Required Expertise

| Challenge Category | Specific Issues | Required Expertise | Solution Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical | Lack of persistent identifier services, metadata registries, ontology services | IT professionals, data stewards, domain experts | Implement chemistry-specific standards (InChI, CIF), use trusted repositories |

| Financial | Establishing/maintaining data infrastructure, curation costs, ensuring business continuity | Business leads, strategy leads, associate directors | Develop long-term data strategy, prioritize high-impact datasets for FAIRification |

| Legal/Compliance | Data protection regulations (GDPR), accessibility rights, licensing | Data protection officers, lawyers, legal consultants | Conduct Data Protection Impact Assessments, implement authentication procedures |

| Organizational | Internal data policies, education/training, cultural resistance | Data experts, data champions, data owners | Develop FAIR organizational culture, provide training, establish clear data management plans |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Does making data FAIR mean I have to make all my data open access?

A: No. FAIR is not synonymous with open data. The Accessibility principle requires that metadata and data should be retrievable using a standardized protocol that may include an authentication and authorization procedure where necessary [10] [12]. Even data with privacy or proprietary issues can be made FAIR through proper access controls.

Q2: What is the minimum metadata required to make chemical data FAIR?

A: At minimum, chemical data should include: machine-readable chemical structures (InChI/SMILES), experimental procedures, instrument settings and calibration data, processing parameters, and clear licensing information [10] [12]. Repository-specific application profiles often provide detailed guidance.

Q3: How do we prioritize which datasets to FAIRify when resources are limited?

A: Prioritization should consider: potential for reuse in answering meaningful scientific questions, alignment with organizational business goals, statistical power of the dataset, available resources for FAIRification, and compliance with funder requirements [11].

Q4: What are the most critical FAIR principles for machine learning applications in drug discovery?

A: For AI/ML applications, Findability (rich metadata for discovery) and Interoperability (standardized formats for integration) are particularly crucial as they enable the aggregation of diverse datasets needed for training robust models [11] [13].

Experimental Protocols for FAIR Data Implementation

FAIRification Workflow for Chemical Data

FAIR Data Implementation Workflow

Protocol: Making Spectral Data FAIR

Objective: Transform raw spectral data (NMR, MS) into FAIR-compliant formats for sharing and reuse.

Materials and Equipment:

- Raw spectral data files

- Electronic Laboratory Notebook (ELN) system

- Domain-specific repositories (e.g., NMRShiftDB for NMR data)

- Metadata standards (e.g., CHMO ontology)

Procedure:

Data Collection and Annotation:

- Export raw instrument data in standard formats (JCAMP-DX for spectral data, nmrML for NMR)

- Record all acquisition parameters (solvent, temperature, field strength, pulse sequences)

- Document processing parameters (window functions, baseline correction, phasing)

Metadata Creation:

- Create structured metadata using community standards

- Include experimental context: sample preparation, concentration, calibration standards

- Use controlled vocabularies (Chemical Methods Ontology - CHMO)

- Link to chemical structures using International Chemical Identifiers (InChIs)

Repository Deposition:

- Select appropriate repository (chemistry-specific when possible)

- Upload data and metadata together

- Obtain persistent identifier (DOI)

- Set access controls if necessary

Quality Assurance:

- Verify metadata completeness using FAIR assessment tools

- Test data download and interpretation by third party

- Ensure machine-readability of all components

Troubleshooting:

- Problem: Proprietary instrument formats hinder interoperability.

- Solution: Convert to open, standard formats (JCAMP-DX, nmrML) before deposition.

- Problem: Incomplete metadata for reproduction.

- Solution: Use electronic lab notebooks with structured templates to capture all relevant parameters during experimentation.

Research Reagent Solutions for FAIR Data Implementation

Table: Essential Tools and Infrastructure for FAIR Chemical Data

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in FAIR Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Persistent Identifiers | Digital Object Identifiers (DOI), International Chemical Identifiers (InChI) | Provides globally unique and persistent identification for datasets and chemical structures [10] [12] |

| Chemistry Repositories | Cambridge Structural Database, NMRShiftDB, Chemotion Repository | Discipline-specific repositories supporting chemistry data types and metadata standards [10] [12] |

| General Repositories | Zenodo, Figshare, Dataverse | General-purpose repositories with chemical data support, DOI assignment, and citation generation [10] [9] |

| Electronic Lab Notebooks | LabArchives, RSpace, eLabJournal | Capture experimental data and metadata at source with structured templates [10] |

| Metadata Standards | DataCite Schema, Chemical Methods Ontology (CHMO), Crystallographic Information Files (CIF) | Standardized frameworks for describing chemical data and experiments [10] [12] |

| Data Visualization | TMAP, UMAP, t-SNE | Tools for exploring and interpreting large chemical datasets [13] |

Advanced FAIR Data Visualization Techniques

TMAP: Large-Scale Chemical Data Visualization

Principle: Tree MAP (TMAP) represents high-dimensional chemical data as two-dimensional trees using a combination of locality-sensitive hashing, graph theory, and tree layout algorithms [13].

Workflow:

- LSH Forest Indexing: Encode chemical structures using MinHash algorithm

- Approximate Nearest Neighbor Graph: Construct c-approximate k-nearest neighbor graph

- Minimum Spanning Tree: Calculate MST using Kruskal's algorithm

- Tree Layout: Generate 2D layout using spring-electrical model with multilevel multipole-based force approximation

Advantages for Chemical Data:

- Handles datasets of up to millions of molecules

- Preserves both global and local neighborhood structure

- Enables visual exploration of chemical space and activity cliffs

- Superior to t-SNE and UMAP for large chemical databases (ChEMBL, FDB17, DSSTox)

TMAP Visualization Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Compliance Framework

Q1: How do OECD Test Guidelines support global chemical regulatory compliance? OECD Test Guidelines provide standardized methodologies for chemical safety testing that enable Mutual Acceptance of Data (MAD) across member countries. This means data generated using these guidelines in one OECD country must be accepted by regulatory authorities in other OECD member countries, reducing duplicate testing and facilitating international chemical registration [14]. Recent updates in June 2025 covered mammalian toxicity, ecotoxicity, and environmental fate endpoints, emphasizing alignment with the 3R principles (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement of animal testing) [14].

Q2: What are the key differences between REACH-like regulations in major markets? While multiple regions have implemented REACH-like chemical management frameworks, significant differences exist in thresholds, classification criteria, and compliance timelines. For example, Korea's K-REACH 2025 amendments introduced a new "unconfirmed hazardous substances" category and raised the annual tonnage threshold for new substance registration to 1 ton per year [15]. The European REACH regulation maintains different requirements for registration, evaluation, authorization, and restriction of chemicals, with recent Annex II updates requiring updated safety data sheets (SDS) [16].

FAIR Data Implementation

Q3: How can FAIR data principles be applied to regulatory chemical data? FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) provide a framework for managing regulatory chemical data to enhance usability and compliance. Implementation includes:

- Findable: Assign persistent identifiers (DOIs) to datasets and use International Chemical Identifiers (InChIs) for chemical structures [17]

- Accessible: Store data in repositories with standard web protocols, ensuring metadata remains accessible even if data has restrictions [17] [1]

- Interoperable: Use community standards like JCAMP-DX for spectral data and CIF for crystal structures [17]

- Reusable: Provide detailed experimental procedures, instrument settings, and clear usage licenses [17]

Q4: What are common interoperability challenges when submitting chemical data across jurisdictions? Interoperability challenges primarily stem from differing data formats, classification criteria, and technical requirements across regulatory regimes. For example, a substance may be classified as hazardous at different concentration thresholds in Korea (e.g., silver nitrate: 1% for environmental hazard) versus other regions [15]. Implementing machine-readable data formats and standardized metadata schemas helps overcome these barriers by enabling automated data processing and cross-referencing [18] [17].

Technical Compliance

Q5: What are the critical testing requirements for "unconfirmed hazardous substances" under K-REACH? For substances classified as "unconfirmed hazardous" under K-REACH 2025 amendments, mandatory test items include:

- Acute oral or inhalation toxicity (OECD TG 423/403)

- Mutagenicity or in vitro chromosomal aberration tests (OECD TG 471/473)

- Acute aquatic toxicity (fish, daphnia, algae) (OECD TG 201/202/203)

- Biodegradability (OECD TG 301) [15]

These requirements apply to new substance notifications submitted on or after August 7, 2025 [15].

Q6: How should Safety Data Sheets (SDS) be updated for 2025 regulatory changes? For compliance with 2025 updates:

- K-REACH: Update Section 15 (Regulatory Information) to include "unconfirmed hazardous substance" status and new human/environmental hazard classifications [15]

- EU REACH: Comply with Annex II amendments (Regulation (EU) 2020/878) for updated SDS format and content [16]

- Transition Period: Old MSDS templates can be used until June 30, 2026, if updated with new classifications; from July 1, 2026, only new versions are valid [15]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Incomplete or Non-FAIR Chemical Data

Symptoms:

- Difficulty locating specific experimental datasets within research groups

- Inability to automatically process analytical data without manual intervention

- Regulatory submissions returned due to missing metadata or non-standard formats

Solution: Table: FAIR Data Implementation Checklist

| FAIR Principle | Implementation Step | Tools & Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Findable | Assign persistent identifiers to datasets | DOI, InChI, SMILES notation [17] |

| Create rich metadata with experimental conditions | Domain-specific metadata templates | |

| Register in searchable resources | Discipline-specific repositories (Cambridge Structural Database, NMRShiftDB) [17] | |

| Accessible | Use standard communication protocols | HTTP/HTTPS, authentication protocols [1] |

| Clarify access conditions | Document authorization requirements | |

| Preserve metadata independently | Ensure metadata accessibility even if data is restricted [17] | |

| Interoperable | Use formal knowledge representation | Semantic models, RDF graphs, ontology-driven models [18] |

| Adopt community standards | CIF files, JCAMP-DX, nmrML [17] | |

| Link related data | Cross-reference datasets and publications [17] | |

| Reusable | Document detailed data attributes | Experimental conditions, instrument settings [17] |

| Specify clear licenses | CC-BY, CC0 standard licenses [17] | |

| Include detailed provenance | Complete data generation workflow [17] |

Problem 2: Cross-Border Regulatory Misalignment

Symptoms:

- Substances approved in one jurisdiction face restrictions in another

- Inconsistent classification and labeling requirements

- Supply chain disruptions due to differing compliance timelines

Solution: Table: Comparative Regulatory Requirements (2025 Updates)

| Regulatory Area | Key Requirement | Effective Date | Threshold/Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| K-REACH New Substance Notification | Increased tonnage threshold | January 1, 2025 | 1 ton/year [15] |

| K-REACH Unconfirmed Hazardous Substances | Additional testing requirements | August 7, 2025 | Acute toxicity, mutagenicity, aquatic toxicity, biodegradability [15] |

| K-REACH Hazard Classification | Replaced "toxic substances" with detailed framework | August 7, 2025 | 1,246 substances reclassified; 19 removed (e.g., ethyl acetate) [15] |

| K-CCA Transitional Measures | Grace periods for newly designated hazardous substances | Before January 1, 2026 | Extended period for benzene (0.1-1%): +2 years [15] |

| OECD Test Guidelines | Updated testing methodologies | June 25, 2025 | 56 new/updated guidelines for mammalian toxicity, ecotoxicity [14] |

Implementation Steps:

- Substance Inventory Review: Map all substances against new thresholds and classifications [15]

- Testing Gap Analysis: Identify required testing for "unconfirmed hazardous substances" [15]

- Documentation Update: Revise SDS Section 15 to reflect new classifications [15]

- Supply Chain Communication: Provide updated compliance information to downstream users [15]

Problem 3: SDS Management Across Multiple Regulations

Symptoms:

- Inconsistent SDS formats across markets

- Difficulty tracking different revision timelines

- Non-compliance with updated classification requirements

Solution: Step 1: Audit existing SDS against 2025 requirements

- Identify substances affected by K-REACH "unconfirmed hazardous" or "human/environmental hazardous" categories [15]

- Check EU REACH Annex II compliance for SDS format and content [16]

Step 2: Implement centralized SDS management

- Utilize digital compliance platforms for version control [16] [19]

- Establish automated alert systems for regulatory updates [19]

Step 3: Coordinate regional updates

- Prioritize high-volume substances and those with changed classifications

- Leverage grace periods where applicable (e.g., K-CCA transitional measures until January 1, 2026) [15]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Regulatory Compliance Testing

| Reagent/Test System | Function | Applicable OECD Test Guideline |

|---|---|---|

| Rodent Models | Acute oral toxicity studies | OECD TG 423 (Acute Oral Toxicity) [15] |

| In Vitro Bacterial Reverse Mutation Test | Mutagenicity screening | OECD TG 471 (Bacterial Reverse Mutation Test) [15] |

| Fish Embryo Acute Toxicity Test | Aquatic toxicity assessment | OECD TG 201/202/203 (Freshwater Fish, Daphnia, Algae) [15] |

| Activated Sludge | Biodegradability testing | OECD TG 301 (Ready Biodegradability) [15] |

| Mason Bees | Acute toxicity to pollinators | New test guideline (2025 update) [14] |

| Aquatic Plants | Toxicity to non-target plants | Updated test guideline (2025) [14] |

| Lutrelin | Lutrelin (CAS 66866-63-5) - For Research Use Only | Lutrelin, a synthetic peptide (CAS 66866-63-5). This product is designated For Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or personal use. |

| Lactose octaacetate | Lactose octaacetate, MF:C28H38O19, MW:678.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Common FAIR Data Implementation Issues

FAQ: Our research team struggles with inconsistent data descriptions. How can we make our chemical data more Findable?

Answer: Inconsistent metadata is a primary barrier to findability. Implement a standardized metadata template enforced at the point of data creation.

- Root Cause: The use of free-text entries, custom labels, and non-standard terminology by different team members locks data in its original context, making it unsearchable [20].

- Solution:

- Adopt Shared Ontologies: Use established chemical ontologies, such as the Allotrope Foundation Ontology (AFO), to describe experiments, materials, and analytical techniques. This ensures machine-interpretability [21].

- Assign Persistent Identifiers (PIDs): Use Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) for your datasets when depositing them in repositories. This provides a permanent, unique link to your data [20].

- Use a Metadata Wizard: Implement a software tool or a simple form that forces researchers to select from predefined, ontology-backed terms when describing a new experiment.

FAQ: Our legacy instruments and software create data silos. How do we achieve Interoperability?

Answer: Interoperability requires data to be structured in standardized, machine-readable formats.

- Root Cause: Fragmented IT ecosystems with proprietary data formats from different instruments (e.g., LIMS, ELNs) lack semantic interoperability, hindering automated integration and advanced analytics [20].

- Solution:

- Implement Standardized Data Models: Convert instrument outputs into community-standard formats. The Allotrope Simple Model (ASM) in JSON (ASM-JSON) is a prime example used for analytical chemistry data to ensure consistency across platforms [21].

- Establish a Data Pipeline with a Semantic Backbone: Develop an automated workflow that ingests raw data, validates it, and converts it into a structured semantic format like the Resource Description Framework (RDF) using a chemical ontology. This creates an interoperable, queryable knowledge graph [21].

- Leverage Containerization: Use platforms like Neurodesk (adapted for chemistry) to package entire software environments. This ensures that the same analytical tools and dependencies are used by everyone, eliminating "works on my machine" problems and ensuring consistent data processing [22].

FAQ: How can we ensure our data is Reusable for colleagues or AI applications in the future?

Answer: Reusability depends on providing rich context and clear licensing.

- Root Cause: Data is often shared without sufficient documentation on its provenance (how it was generated), the specific methods used, or the terms of use [20].

- Solution:

- Document Comprehensive Provenance: Systematically record every experimental step, from automated synthesis parameters to analytical instrument settings. Crucially, this must include both successful and failed experiments to create bias-resilient datasets for AI training [21].

- Create "Matryoshka" Files: Package all components of an experiment—raw data, processed data, and the complete metadata—into a single, standardized ZIP file. This portable format ensures all context is preserved for future reuse [21].

- Define Clear Licensing: Attach a clear usage license (e.g., Creative Commons) to your dataset so others know exactly how they can legally use it [20].

Quantitative Evidence: The Impact of FAIR and Reproducible Practices

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings on data sharing challenges and the benefits of reproducible practices.

Table 1: Data Sharing Challenges and Reproducibility Benefits

| Area | Key Finding | Source / Study | Quantitative Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Availability | Rate of successful data sharing upon request. | Tedersoo et al. (2021) [23] | Average of 39.4% across disciplines (range: 27.9% - 56.1%). |

| Data Sharing Compliance | Authors providing data after stating they would. | Gabelica et al. (2022) [23] | Only 6.8% of authors provided data upon request. |

| Clinical Trial Data Sharing | Availability of individual participant data. | Narang et al. (2023) [23] | Available for only 3.3% of NIH-funded pediatric trials. |

| AI Project Success | Organizational trust in their own data. | DATAVERSITY Trend Report [24] | 67% of organizations lack trust in their data for decision-making. |

| Research Impact | Effect of reproducible practices on citation. | BMC Research Notes (2021) [25] | Work adopting reproducible practices is more widely reused and cited. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Implementing a FAIR Research Data Infrastructure (RDI)

This protocol is based on the HT-CHEMBORD platform developed at the Swiss Cat+ West hub, EPFL, for high-throughput digital chemistry [21].

Objective: To create an automated, end-to-end digital workflow that captures all experimental data and metadata in a structured, FAIR-compliant manner, enabling reproducibility, advanced querying, and AI-ready datasets.

Workflow Diagram: The following diagram visualizes the core architecture and data flow of a FAIR RDI for automated chemistry.

Methodology:

Project Initialization:

- Action: A researcher uses a Human-Computer Interface (HCI) to digitally define the experiment.

- Key Output: A structured JSON file containing all initial metadata: reaction conditions, reagent structures (e.g., SMILES), and batch identifiers. This ensures traceability from the very beginning [21].

Automated Synthesis and Analysis:

- Action: Synthesis is performed by automated platforms (e.g., Chemspeed). Parameters (temperature, pressure, stirring) are logged by control software (e.g., ArkSuite) into a JSON file [21].

- Action: Samples then enter a multi-stage analytical workflow (see diagram). Based on decision points (e.g., signal detection, chirality), they are routed through various techniques (LC-MS, GC-MS, SFC, NMR).

- Critical Step: The system is designed to capture data from all branches, including failed reactions and negative results, which are vital for robust AI training [21].

Structured Data Capture:

- Action: All analytical instruments are configured to output data in standardized, machine-actionable formats.

- Primary Format: The Allotrope Simple Model in JSON (ASM-JSON) is used for techniques like LC-MS and GC-MS to ensure consistency. Other formats like XML or proprietary data with standardizers may be used for other instruments [21].

Semantic Enrichment and Storage (The "FAIRification" Engine):

- Action: An automated pipeline (e.g., built on Kubernetes and Argo Workflows) runs on a schedule.

- Core Process: A modular RDF Converter maps the raw structured data (JSON/XML) to a semantic model using a chemical ontology (e.g., AFO). This transforms the data into RDF triples, creating a powerful and interoperable knowledge graph [21].

- Storage: The resulting RDF graphs are loaded into a triplestore (a semantic database).

Access and Reuse:

- Action: The stored FAIR data is made accessible through:

- A user-friendly web interface for browsing and searching.

- A SPARQL endpoint for expert users to perform complex, cross-dataset queries [21].

- Packaging: For sharing, complete experiments can be packaged into "Matryoshka files" (ZIP archives), containing all raw data, processed data, and metadata for maximum reusability [21].

- Action: The stored FAIR data is made accessible through:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Digital & Infrastructure "Reagents" for a FAIR Lab

| Item / Solution | Function in the FAIR Workflow |

|---|---|

| Allotrope Foundation Ontology (AFO) | A standardized vocabulary (ontology) for representing chemical experiments and data. Provides the semantic definitions for Interoperability [21]. |

| Allotrope Simple Model (ASM) | A standardized data model for packaging analytical data and metadata. Ensures Interoperability between different instruments and software [21]. |

| Kubernetes & Argo Workflows | Container orchestration and workflow management platforms. Automate the entire data processing pipeline, from capture to semantic conversion, ensuring scalability and Reusability [21]. |

| Resource Description Framework (RDF) | A standard model for data interchange on the web. Represents data as subject-predicate-object triples, forming a knowledge graph that is inherently Interoperable and queryable [21]. |

| SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language (SPARQL) | The query language for RDF databases. Allows researchers to ask complex, cross-domain questions of their FAIR data, unlocking its value for discovery [21]. |

| Neurocontainers / Docker Containers | Containerized software environments that package a tool and all its dependencies. Ensure computational Reproducibility across different computers and operating systems [22]. |

| Open Reaction Database (ORD) | A community-shared database for structured chemical reaction data. Serves as both a target repository for Sharing and a source of Reusable data for AI training [21]. |

| Kushenol B | Kushenol B, MF:C30H36O6, MW:492.6 g/mol |

| (-)-Lyoniresinol | (-)-Lyoniresinol|Lignan |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the FAIR Principles and why are they critical for cross-disciplinary chemical research?

The FAIR Principles are a set of guiding principles to make digital assets, including data and metadata, Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable [1]. The principles emphasize machine-actionability, which is the capacity of computational systems to find, access, interoperate, and reuse data with minimal human intervention [1]. This is especially crucial in chemical research as data volume and complexity grow. For cross-disciplinary work, FAIR ensures that chemical data can be seamlessly integrated with biological and environmental datasets, enabling comprehensive analysis and discovery [9] [10].

FAQ 2: How can I make my chemical data Findable?

To ensure your chemical data is findable:

- Assign globally unique and persistent identifiers (e.g., a DOI for your dataset, InChI keys for chemical structures) [10].

- Create rich, machine-readable metadata that describes the data in detail [1].

- Register or index your data and its metadata in a searchable resource or repository [1]. Discipline-specific examples include the Cambridge Structural Database for crystallographic data or NMRShiftDB for NMR data [10].

FAQ 3: What does Interoperability mean in practice for a chemist?

Interoperability means that your data can be integrated with other data and used with applications or workflows for analysis, storage, and processing [1]. In practice, this requires:

- Using formal, shared, and broadly applicable languages and formats for data and metadata (e.g., CIF for crystal structures, JCAMP-DX for spectral data, nmrML for NMR data) [10].

- Adopting community-agreed standards and controlled vocabularies to describe chemical processes and experimental conditions [10].

- Ensuring data includes cross-references to other (meta)data, establishing relationships between datasets [1].

FAQ 4: My data is proprietary. Can it still be FAIR?

Yes. The FAIR principles are about making data As Open as Possible, As Closed as Necessary [10]. "Accessible" does not mean "open." It means that metadata should always be accessible to describe the data, and that even when the data itself is restricted, there is a clear and standard protocol (which may include authentication and authorization) for how it can be accessed under specific conditions [1] [10].

FAQ 5: What are the most common pitfalls that make chemical data non-reusable?

The most common pitfall is a lack of sufficient documentation and provenance. Data must be well-described so that they can be replicated and/or combined in different settings [1]. Key omissions include:

- Incomplete experimental procedures and sample preparation details.

- Missing instrument settings and calibration data.

- Unclear data processing steps.

- Absence of a clear usage license [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Data Silos and Fragmented Information

- Symptoms: Inability to locate existing internal data; redundant experiments being performed; difficulty combining data from different departments (e.g., chemistry and biology) for a unified analysis.

- Root Cause: Reliance on static file systems (e.g., unconnected PowerPoint slides, Excel spreadsheets, emails) that lack chemical awareness and create information barriers [26].

- Solution:

- Centralize Data Management: Implement a centralized, chemically-aware data management platform or electronic lab notebook (ELN) that serves as a single source of truth [27] [26].

- Establish Standardized Protocols: Use customizable templates within your ELN for standardized experimental protocols to ensure consistent data entry and integrity [27].

- Implement Real-Time Collaboration Tools: Utilize platforms that offer real-time notifications, simultaneous document editing, and robust project tracking to keep cross-functional teams aligned [27].

Problem 2: Non-Interoperable Data Formats

- Symptoms: Inability to computationally integrate a dataset from a public repository with in-house data; errors when importing data into analysis software; significant time spent on manual data "wrangling" and reformatting.

- Root Cause: Use of proprietary, non-standard, or poorly documented data formats that machines cannot automatically interpret [28] [10].

- Solution:

- Adopt Community Standards: Forge data using standard, machine-readable formats from the outset. The table below summarizes key standards in chemistry.

| Data Type | Recommended Standard(s) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Structure | InChI, SMILES | Machine-readable structure representation [10] |

| Crystallography | Crystallographic Information File (CIF) | Standard for reporting crystal structures [10] [29] |

| Spectroscopy (General) | JCAMP-DX | Standard format for spectral data exchange [10] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | nmrML | Standardized format for NMR data [10] |

| Chemical Reactions & Synthesis | Machine-readable reaction formats (e.g., V3000) | Structuring synthesis routes for reproducibility and automated scripts [28] [10] |

Problem 3: Insufficient Metadata for Reuse

- Symptoms: Other researchers (or yourself after several months) cannot understand how the data was generated or reproduce the results; biological or environmental context of a chemical dataset is lost.

- Root Cause: Metadata (data about the data) is incomplete, unstructured, or stored separately from the raw data [9].

- Solution:

- Follow a Metadata Checklist: For every dataset, ensure the following metadata is captured and stored with the data.

- Link to Related Data: Use identifiers to cross-reference your chemical data to relevant biological (e.g., assay results in a public database) or environmental (e.g., sampling location data) datasets [9] [10].

Table: Essential Metadata Checklist for Reusable Chemical Data

| Metadata Category | Specific Examples | |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Conditions | Concentrations, temperatures, pressures, reaction times [10] | |

| Sample Information | Source, preparation method, handling procedures [10] | |

| Instrumentation & Acquisition | Instrument model, software version, acquisition parameters (e.g., for NMR: magnetic field strength, pulse sequence) [30] [10] | |

| Data Processing | Software used, processing steps and parameters (e.g., baseline correction, normalization methods) [30] | |

| Provenance | Full data generation and transformation workflow [10] | |

| Licensing | Clear, machine-readable license (e.g., CC-BY, CC-0) [10] |

Problem 4: Visualizing Complex Cross-Disciplinary Data for Insight

- Symptoms: Difficulty identifying patterns or trends in large, multi-dimensional datasets (e.g., metabolomics data); inability to effectively communicate findings to collaborators from other disciplines.

- Root Cause: Use of inappropriate or non-scalable visualization techniques for complex data; lack of interactive visual tools [31] [30].

- Solution:

- Select Fit-for-Purpose Visualizations: Match the visualization technique to the analytical question. The crystallography community's adoption of standardized data exchange has been a key driver of its interoperability [29].

- Leverage Interactive Tools: Use modern visualization software that allows for dynamic filtering, zooming, and data exploration to facilitate insight during live sessions and collaborative analysis [31] [26].

FAIR Data Enables Integrated Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key digital "reagents" and infrastructure components essential for implementing FAIR chemical data practices in a cross-disciplinary context.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) | A digital platform for recording experimental data, procedures, and observations in a structured manner. Facilitates real-time collaboration, data integrity, and serves as the primary source for metadata collection [27] [26]. |

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | Automates the tracking of samples, reagents, and associated data. Manages inventory, workflows, and integrates with instruments to capture data provenance automatically [27]. |

| International Chemical Identifier (InChI) | A standardized, machine-readable identifier for chemical substances. Provides a unique and unambiguous way to represent chemical structures across different software platforms and databases, crucial for interoperability [10]. |

| Discipline-Specific Repositories (e.g., Cambridge Structural Database, NMRShiftDB) | Curated repositories that accept specific types of chemical data. They often enforce community standards, provide persistent identifiers (DOIs), and enhance the findability and long-term preservation of data [10]. |

| General-Purpose Repositories (e.g., Zenodo, Figshare) | Repositories for publishing and sharing diverse research outputs, including datasets that may not fit into a discipline-specific database. They provide DOIs and support the findability and accessibility principles [9] [10]. |

| Standard Data Formats (e.g., CIF, nmrML, JCAMP-DX) | Community-agreed file formats for representing specific types of chemical data. Their use is fundamental to achieving interoperability, as they ensure data can be interpreted by different software and platforms [10] [29]. |

| Stachybotrylactam | Stachybotrylactam, MF:C23H31NO4, MW:385.5 g/mol |

| Ac-LEHD-CHO | Ac-LEHD-CHO, MF:C23H34N6O9, MW:538.6 g/mol |

Data Integration Across Disciplines

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: How to Identify and Break Down Data Silos

Problem Statement: Data is trapped within specific departments (e.g., analytical chemistry, pharmacology), leading to incomplete datasets, duplicated efforts, and an inability to get a unified view of research data [32] [33].

Diagnosis Steps:

- Conduct a Data Audit: Proactively identify silos by documenting all data sources, storage locations, and owning teams across the organization [34].

- Look for Operational Symptoms: Listen for user reports of difficulty compiling reports, time-consuming manual data reconciliation, or receiving conflicting reports from different teams that should contain the same data [34].

- Check for Incompatible Systems: Identify legacy systems (e.g., specialized analytical instrument software) or department-specific applications that cannot connect with newer technologies [32].

Resolution Steps:

- Modernize Data Architecture: Implement a unified data platform like a data lakehouse, which combines the flexibility of data lakes for raw data (e.g., spectral files) with the governance and performance of data warehouses [34].

- Implement Data Integration Tools: Use Extract, Transform, Load (ETL) or Extract, Load, Transform (ELT) pipelines to automate the secure movement of data from isolated silos into a central repository [32] [34].

- Establish a Data Governance Framework: Develop clear policies for data ownership, access controls, and standardized procedures for data sharing. This ensures data is accessible yet secure [32].

- Foster a Collaborative Culture: Encourage cross-functional teams and secure executive support to shift from a culture of data ownership to one of data sharing [32] [33].

Guide 2: How to Resolve Data Inconsistency

Problem Statement: The same data element (e.g., a compound identifier or concentration value) has different values across systems, compromising data integrity and leading to flawed analyses [35].

Diagnosis Steps:

- Perform Cross-Platform Spot Checks: Manually compare a random sample of records (e.g., 50 compounds) across your CRM, ELN, and data warehouse for mismatches in key fields [35].

- Monitor for Unexplained Anomalies: Investigate sudden spikes or drops in key metrics that lack a clear business explanation, as this often indicates a broken data pipeline [35].

- Check for Duplicate Records: Identify multiple entries for the same entity (e.g., a chemical with slightly different names) which signals fragmented data [35].

- Audit for Schema Drift: Detect changes in data structure (e.g., a column rename or data type change) that can break integrations and cause downstream errors [35].

Resolution Steps:

- Automate Data Synchronization: Use APIs and data pipeline tools to ensure an update in one system automatically propagates to all others, eliminating manual entry [35].

- Establish a Single Source of Truth: Designate one authoritative database for critical entities (e.g., chemical compounds) and have all other systems sync from it [35].

- Implement Data Entry Standards: Create and enforce uniform formats for data input (e.g., standardized chemical nomenclature and date formats) to prevent errors at the source [35].

- Build in Validation Checks: Use automated rules at data entry points to reject invalid formats (e.g., an incorrect CAS number format) immediately [35].

Guide 3: How to Implement Provenance Tracking for FAIR Compliance

Problem Statement: The origin, history, and processing steps of chemical data are not adequately documented, making it difficult to reproduce experiments, validate results, and meet FAIR principles, especially for machine-driven discovery [1] [9].

Diagnosis Steps:

- Audit Current Data Lineage: Trace a sample dataset from its raw form (e.g., instrument output) through all processing steps to its final form in a publication. Document any missing information about transformations or handlers.

- Check for Machine-Actionability: Assess if metadata is stored in a structured, standardized format that computational agents can automatically parse and interpret without human intervention [9].

- Interview Researchers: Identify manual, non-standardized documentation practices (e.g., notes in physical lab books or disparate digital files) that break the provenance chain [36].

Resolution Steps:

- Use Electronic Lab Notebooks (ELNs): Implement an ELN to structurally document the entire data lifecycle, from experiment planning and execution to analysis [36].

- Adopt Standardized Metadata Schemas: Use domain-specific standards (e.g., Bio-Assay Ontology - BAO) to annotate datasets consistently, ensuring interoperability [37].

- Implement a Data Engineering Pipeline: Develop scalable pipelines, as demonstrated in chemical flow analysis research, that automatically capture and link data across its lifecycle, including information about the source, transformations, and reliability scores [38].

- Leverage Data Fabrics: Utilize a data fabric architecture that uses metadata management systems to actively track and manage data provenance, connecting disparate data stores in real-time [32].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the root causes of data silos in a pharmaceutical research environment? Data silos arise from a combination of factors:

- Organizational Structure: Different departments (e.g., medicinal chemistry, toxicology) use specialized tools and workflows, creating natural barriers to data sharing [32] [33].

- Technology Complexity: Legacy instrument data systems and proprietary software often lack the integration capabilities to connect with modern data platforms [32].

- Company Culture: Teams may view their data as a proprietary asset, restricting access due to a perceived competitive advantage or a simple lack of incentive to share [32].

FAQ 2: We have multiple databases. How does that lead to data inconsistency? Storing data in multiple locations (data redundancy) is not inherently bad, but it becomes problematic without proper management. Inconsistency occurs when:

- An update in one database (e.g., a compound's solubility in the ELN) fails to synchronize with another database (e.g., the central screening library) [35].

- Different systems have varying update frequencies (real-time vs. nightly batches), creating temporary inconsistencies that can become permanent [35].

- There is a lack of a clear "single source of truth" to dictate which data source is authoritative [35].

FAQ 3: Why is provenance tracking critical for FAIR chemical data? Provenance is the backbone of the Reusability and Reproducibility principles in FAIR. It provides the critical context needed for others (both humans and machines) to:

- Understand how data was generated and processed.

- Trust the quality and reliability of the data.

- Reproduce experimental outcomes accurately [9].

- Integrate datasets from different sources with confidence [38].

FAQ 4: What is a practical first step to make our chemical assay data more FAIR? A highly effective first step is to focus on Findability. Ensure all datasets are assigned rich, machine-readable metadata using a standardized ontology like the Bio-Assay Ontology (BAO) [37]. Then, register or index these datasets in a searchable institutional or public repository. This makes your data easily discoverable for your future self and the broader community, which is the essential first step in the data reuse cycle [1].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common Data Inconsistencies and Their Impact

| Data Element | Example of Inconsistency | Potential Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Identifier | "4-(4-chlorophenyl)-..." in ELN, "4-(4-Cl-Ph)-..." in report | Inability to accurately search, link, or aggregate all data for a compound [35]. |

| Biological Assay Result | IC50 = 1.2 µM in primary data, reported as 1200 nM in publication | Errors in dose-response modeling and incorrect structure-activity relationship (SAR) conclusions [35]. |

| Sample Concentration | 10 mM in stock record, 0.01 M in experiment log | Introduction of significant errors in experimental replication and biological interpretation [35]. |

| Unit of Measurement | Weight recorded in mg, but processed as µg in analysis | Severe miscalculations and invalid experimental results [35]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing a FAIRness Check for a Chemical Dataset

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology to assess and improve the FAIRness of a typical chemical dataset, such as a collection of compound activity data.

1. Objective: To evaluate a dataset against the FAIR principles and implement corrections to enhance its findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Dataset: The chemical data to be evaluated (e.g., a CSV file of compound structures and bioactivity values).

- Metadata Schema: A standardized schema, such as parts of the Bio-Assay Ontology (BAO) [37].

- Repository: Access to a suitable data repository (e.g., institutional repository, Zenodo, or a chemistry-specific platform).

- Provenance Tracking Tool: An Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) or a workflow management system that can capture data history [36].

3. Experimental Workflow:

4. Procedure: 1. Findability (F): * Ensure the dataset is assigned a Globally Unique and Persistent Identifier (PID), such as a DOI or an accession number [1]. * Describe the dataset with rich, machine-readable metadata. Use a structured vocabulary like BAO to annotate key elements such as target protein, assay type, and measured endpoints [37]. 2. Accessibility (A): * The metadata should be retrievable by its identifier using a standardized communication protocol like HTTPS, even if the data itself is under restricted access [1] [9]. * Clearly specify the license and terms of use for the data. 3. Interoperability (I): * Use formal, accessible, and broadly applicable knowledge representation languages (e.g., RDF, JSON-LD) to structure the data and metadata [9]. * Use standardized ontologies and vocabularies (e.g., ChEBI for chemicals, BAO for assays) to represent the data, minimizing free-text fields to ensure semantic interoperability [37]. 4. Reusability (R): * Provide detailed provenance information that describes the origin of the data and the processing steps it underwent. This should be documented in an ELN or similar system [36]. * The dataset should be richly described with multiple relevant attributes and meet domain-relevant community standards for data curation [1].

5. Analysis and Notes:

- The success of this protocol can be measured by the ability of a colleague (or a computational agent) to find, understand, and correctly reuse the dataset without requiring additional guidance.

- The most common point of failure is incomplete or non-standard metadata, which severely limits Findability and Interoperability.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for FAIR Data Management

| Item | Function in Data Management |

|---|---|

| Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) | A digital platform for structurally documenting experiments, protocols, and results. It is crucial for capturing data provenance and ensuring experimental reproducibility [36]. |

| Standardized Ontologies (e.g., BAO, ChEBI) | Controlled vocabularies that provide consistent terms for describing biological assays, chemical entities, and their properties. They are fundamental for achieving semantic Interoperability [37]. |

| Data Lakehouse | A modern data architecture that serves as a central repository. It combines the cost-effectiveness and flexibility of a data lake (for raw data) with the management and performance features of a data warehouse, helping to break down data silos [34]. |

| ETL/ELT Tools | Software that automates the process of Extracting data from source systems, Transforming it into a consistent format, and Loading it into a target database. This is key to resolving data inconsistency and integrating siloed data [32] [34]. |

| Persistent Identifier (PID) Service | A system (e.g., DOI, Handle) for assigning a permanent, globally unique identifier to a digital object (a dataset). This is the cornerstone of Findability in the FAIR principles [1] [9]. |

| 1,3,5-Tricaffeoylquinic acid | 1,3,5-Tricaffeoylquinic Acid|High-Purity Reference Standard |

| Glomeratose A | Glomeratose A, MF:C24H34O15, MW:562.5 g/mol |

Practical Implementation: Building FAIR Chemical Data Workflows

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals address common technical issues. The guidance is framed within the context of managing FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) chemical data research [39].

Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) troubleshooting guides

Q: Why can't I access the ELN even though its services are running?

This problem can occur even when the ELN and database (DB) services are confirmed to be live [40].

Step-by-Step Diagnosis:

- Check Basic Network Connectivity: Ping the database server from the application machine to verify basic network connectivity [40].

- Test Database Connectivity: Use a tool like

TNSPING(for relevant databases) from the application machine to the database server [40]. - Investigate Hostname Resolution: If the ping works with an IP address but not with a hostname, there may be a Domain Name System (DNS) configuration issue [40].

- Check Network Interface Configuration: A misconfigured network interface card (NIC) on the server can cause connection failures. Verify that the primary NIC is enabled and that network routes are correct. A temporary solution might involve disabling a backup NIC that is interfering with traffic [40].

Q: How do I troubleshoot unresponsive ELN processes?

Use the nsrwatch utility, available in some ELN environments, to monitor and troubleshoot core processes that appear hung or are consuming high system resources [41].

Prerequisites and Commands:

| Operating System | Prerequisites | Example Command |

|---|---|---|

| Windows | Install Debugging Tools for Windows; ensure cdb.exe is in the PATH; obtain symbol files (.pdb) from support [41]. |

nsrwatch -p nsrd -i 10 -t 10 -k 10 -S E:\Symbols > E:\Logs\nsrwatch.nsrd 2>&1 [41] |

| Linux | Install non-stripped binaries for the process of interest (e.g., nsrd, nsrjobd), usually provided by support [41]. | nsrwatch -p nsrd -i 30 -t 30 -k 30 > nsrd_out [41] |

Explanation of nsrwatch Options:

| Option | Function |

|---|---|

-p program |

Specifies the RPC program name (e.g., nsrd, nsrjobd) [41]. |

-i interval |

Sets the interval (in seconds) between server queries [41]. |

-t threshold |

Sets the threshold (in seconds) before reporting a responsiveness issue [41]. |

-k interval |

Sets the interval (in seconds) between logging of stack traces [41]. |

-S dir |

(Windows) Path to symbol (.pdb) files [41]. |

Q: What should I check before using advanced troubleshooting tools?

Before using tools like nsrwatch, rule out more common causes [41]:

- Verify System Resources: Check for adequate disk space, CPU, and RAM availability on the server [41].

- Review Logs: Check operating system logs (e.g.,

/var/log/messageson Linux, Event Viewer on Windows) for significant errors [41]. - Confirm Software Compatibility: Ensure all elements of your system are using supported and compatible versions [41].

FAIR data management and repository FAQs

Q: What is a "trustworthy" data repository and how do I select one?

A trustworthy repository, often certified, is crucial for the long-term preservation and accessibility of your data, a key requirement of the FAIR principles [42].

Selection Criteria:

- Prefer Certified Repositories: Look for repositories certified by standards like CoreTrustSeal, Nestor Seal, or ISO 16363 [42].

- Use a Disciplinary Repository: Always check if there is a community-accepted repository for your specific field [42].

- Utilize Institutional or General Repositories: If no disciplinary repository exists, use your institutional repository or a general-purpose one like Zenodo [42].

- Search Global Registries: Use registries like re3data or FAIRsharing to discover fitting repositories; filter for those with certifications [42].

Q: What are the key requirements for preparing FAIR data for reuse?

Preparing FAIR data ensures it is machine-readable and reusable by others, which is increasingly mandated by funders [39].

FAIR Data Preparation Checklist [39]:

| Category | Key Actions |

|---|---|

| Dataset/Files | Deposit in an open, trusted repository; assign a persistent identifier (e.g., DOI); use standard, open file formats; ensure data is retrievable via an API. |

| README/Metadata | Describe all files and software requirements; use disciplinary terminology and notation; include machine-readable standards (e.g., ORCIDs, ISO date format); provide a clear data citation and license. |

Workflow Diagram: Preparing FAIR Data for Repository Deposit

ELN selection and feature comparison

Q: What should I look for in an ELN to ensure compliance with modern data policies?

To comply with policies like the NIH 2025 Data Management and Sharing Policy, your ELN should support [43]:

- Centralized and Structured Data Capture: A unified platform for all data types [43].

- Version Control and Audit Trails: Tamper-proof records of changes [43].

- Metadata Management: Standardized fields to make data FAIR [43].

- Integration with Repositories: Seamless export to institutional or public data repositories [43].

Comparison of Top ELN Platforms (2025-2026)

| Tool Name | Best For | Standout Feature | Key AI/Automation Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genemod | Biopharma R&D, Diagnostics [44] | Unified AI-driven ELN & LIMS [44] | AI chatbot, data analysis, protocol generation [44] |

| Benchling | Biotech, Pharma (Molecular Biology) [45] | DNA sequencing & CRISPR tools [45] | (Next-gen platforms offer AI data analysis) [44] |

| SciNote | Academic, Small Teams [45] | Open-source flexibility [45] | Structured workflows for task management [45] |

| LabArchives | Academic, Regulated Labs [45] | Advanced metadata search [45] | Compliance with FDA 21 CFR Part 11 [45] |

| Scispot | Biotech, Diagnostic Labs [46] | AI-powered automation & compliance [46] | Predictive analytics for equipment maintenance [46] |

Decision Guide:

- Small Academic Labs:

SciNote,Labfolder(free tiers) [45]. - Biotech/Pharma:

Benchling(biology focus),Scispot(AI automation) [45] [46]. - Regulated Industries:

LabArchives,LabWare ELN(robust compliance) [45]. - Custom Workflows:

Labii(pay-per-use, highly customizable) [45].

Research reagent solutions

Essential Materials for FAIR Chemical Data Research

| Item / Solution | Function in Research Context |

|---|---|

| Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) | Digital platform for centralizing experiment documentation, ensuring data integrity, and enabling secure collaboration [43]. |

| Inventory Management System | Tracks reagents, samples, and materials, often integrated with ELNs to link data directly to physical resources [47]. |

| Safety Data Sheet (SDS) Software | Automates the creation and management of SDSs and Technical Data Sheets, ensuring regulatory compliance (e.g., GHS, OSHA) and safe handling [48]. |

| Trustworthy Data Repository | Provides a certified, long-term home for research data, assigning persistent identifiers (DOIs) to ensure findability and citability [42]. |

| Metadata Standards & Templates | Structured schemas (e.g., using defined fields for units, methods) that make data interoperable and reusable by humans and machines [39]. |

Logical Workflow: From Experiment to FAIR Data Sharing

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between InChI, MInChI, and NInChI?

A1: These identifiers serve different levels of chemical complexity. The International Chemical Identifier (InChI) is a standardized, machine-readable representation of a pure chemical substance, encoding molecular structure into a layered string [49]. The Mixture InChI (MInChI) extends this concept to describe mixtures of multiple chemical components, specifying their relative proportions and roles within the mixture [50]. The Nano InChI (NInChI) is a proposed extension to uniquely represent nanomaterials, which are complex multi-component systems. It captures information beyond basic chemistry, such as core composition, size, shape, morphology, and surface functionalization [50] [51].

Q2: Why should our research team invest time in implementing these identifiers for FAIR data?

A2: Implementing InChI and its extensions is a cornerstone for achieving FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles [10] [52]. They provide a canonical, non-proprietary standard that makes your data machine-readable and searchable across different databases and software platforms. This prevents the "data fragmentation" common in nanotechnology and materials science, enhances reproducibility, and enables advanced data mining and AI/ML applications by providing structured, high-quality input data [53] [54].

Q3: We work with nanomaterials. What specific properties can a NInChI capture?

A3: The proposed NInChI uses a hierarchical, "inside-out" structure to capture critical nanomaterial characteristics [53]. The key layers include:

- Chemical Core: The fundamental composition (e.g., gold, silica) [53].

- Morphology: Physical characteristics like size, shape (e.g., sphere, rod), and structure [50] [53].

- Surface Properties: Aspects such as charge, roughness, and crystallographic form [50].

- Surface Chemistry & Ligands: The identity, attachment mode (e.g., covalent), and density of molecules attached to the surface [50] [53]. This layered approach allows the NInChI to distinguish between different "nanoforms" of the same chemical substance, a critical requirement under regulatory frameworks like REACH [51].

Q4: Where can I find tools and resources to generate and learn about these identifiers?

A4: Several key resources are available:

- InChI Trust: The official source for the InChI software, documentation, and the InChI Open Education Resource (OER), which contains over 100 training materials, articles, and presentation files [49].

- NInChI Prototype Web Interface: A working prototype for generating NInChI strings, providing a user-friendly platform for testing and community feedback [53].

- NanoCommons Knowledge Base: Actively working to integrate NInChI to demonstrate its utility for data search and integration within the nanosafety community [51].

Troubleshooting Common Implementation Issues

Problem: Inconsistent or non-canonical structure representations causing failed database matches.

- Issue: The same molecule can be drawn in different ways, leading to different initial connection tables. If the identifier generation process is not canonical, the same substance will have different strings, breaking database searches.

- Solution: Always use the official, canonical InChI algorithm from the InChI Trust for generating identifiers. The InChI algorithm is designed to produce the same string for the same molecule regardless of how the input structure was drawn [49]. This is a key advantage over other notations like SMILES, where canonicalization can be vendor-dependent [54] [49].

- FAIR Data Link: This directly ensures Interoperability and Reusability by providing a consistent, standard representation that can be reliably used across different systems and over time [10].

Problem: Representing complex nanomaterials and mixtures beyond simple molecules.

- Issue: Standard InChI is designed for a single, discrete molecular structure. It cannot encode the multi-component nature of a mixture or the physico-chemical properties of a nanomaterial.

- Solution: Utilize the appropriate extensions. For mixtures, use MInChI [50]. For nanomaterials, the developing standard is NInChI [50] [51]. The NInChI working group is actively defining the layers and sublayers needed to capture nanomaterial complexity, building on the established InChI framework.

- FAIR Data Link: Using the correct identifier for the material type ensures the data is Findable by others working with similar complex substances and is Reusable with the proper context [52].

Problem: Legacy data and proprietary file formats are not machine-readable.

- Issue: Historical data is often locked in proprietary or obsolete instrument vendor formats, making it inaccessible for modern data analysis and AI/ML workflows.

- Solution: As part of a FAIRification process, develop a strategy to standardize data into open or standardized formats. This can involve using open standards like JCAMP-DX for spectra or vendor-agnostic data converters that transform legacy data into machine-readable formats (e.g., JSON) [52]. For new data, implement policies to store data in standardized, non-proprietary formats at the point of creation.

- FAIR Data Link: This is fundamental to Accessibility and Interoperability. It ensures data can be retrieved and used with common protocols and tools, independent of the original, often proprietary, software [10] [52].

Problem: Lack of metadata and context makes generated identifiers less useful.

- Issue: An InChI string alone may not provide sufficient experimental context for the data to be truly reusable. For example, a NInChI for a nanoparticle might not specify the synthesis method, which can influence its properties.

- Solution: Always associate the chemical identifier with rich, structured metadata. This includes experimental parameters, instrument settings, sample preparation details, and the provenance of the data. Use community-agreed metadata standards, taxonomies, and ontologies to describe the data consistently [10] [52].

- FAIR Data Link: Comprehensive metadata is the key to Reusability. It allows others to understand, replicate, and combine datasets with confidence [10].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Generating a Standard InChI for a Small Molecule

This protocol ensures a canonical, machine-readable identifier is generated from a chemical structure.

- Structure Input: Begin with a correctly drawn 2D chemical structure. This can be from a molecular drawing tool (e.g., ChemDraw), an electronic lab notebook, or a structure file (e.g., MOL file).

- Software Selection: Use software that incorporates the official InChI algorithm from the InChI Trust. This can be a standalone tool, a plugin for your drawing package, or an integrated feature in a database like PubChem or ChemSpider.

- Generation: Execute the InChI generation function. The software will create a connection table and apply the InChI algorithm to produce the layered string.

- Verification: Validate the output by copying the InChI string and using a reverse-engineering tool (like the PubChem Sketcher) to confirm it regenerates the correct chemical structure [49].

- Storage and Linking: Store the InChI and its compact hash, the InChIKey, in your database alongside the chemical data. Use the InChIKey for fast web searches [50].

Protocol 2: Defining a Nanomaterial for NInChI Encoding

This methodology outlines the key parameters that must be characterized and documented to generate a meaningful NInChI string.

- Core Characterization:

- Morphological Analysis:

- Measure the size and size distribution (e.g., mean diameter of 20 nm).

- Characterize the shape (e.g., spherical, rod, sheet).

- Use techniques like Electron Microscopy (TEM/SEM) and Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) for this step.

- Surface Analysis:

- Data Integration for NInChI:

- Input the characterized parameters into the NInChI generation tool [53].

- The tool will assemble the data according to the NInChI layers to produce the final identifier string.

The following diagram visualizes this hierarchical workflow for defining a nanomaterial, from core analysis to the final NInChI string:

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential tools and resources for implementing chemical identifiers in a FAIR data environment.

| Resource Name | Function / Role | Relevance to FAIR Data |

|---|---|---|

| InChI Trust Software & OER [49] | The official, canonical generator for standard InChI strings and a repository of educational materials. | Ensures Interoperability by providing a single, open-source standard for chemical representation. |

| NInChI Prototype Web Tool [53] | A working platform for generating and testing NInChI strings based on the alpha specification. | Makes nanomaterial data Findable and Reusable by providing a structured, machine-readable descriptor. |

| Allotrope Framework [52] | A set of standards and models for representing analytical data in a structured, open format. | Enhances Interoperability by standardizing complex analytical data, making it usable across different systems. |

| Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) | A digital system for recording experimental data and metadata in a structured way. | Critical for Reusability, as it captures the essential metadata and provenance required to understand data. |

| Standardized Metadata Ontologies [52] | Controlled vocabularies that define terms and relationships for describing data. | Teaches machines to read data, enabling Interoperability and making data Reusable for new applications. |

Table 1: Comparison of InChI Standard Versions

| Identifier | Primary Scope | Key Encoded Information | Example Use Case in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| InChI [49] | Discrete, small molecules | Atomic connectivity, stereochemistry, isotopic composition, charge. | Uniquely identifying an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) in a database. |

| MInChI [50] | Chemical mixtures | Identity and relative proportions of all components (solvents, solutes, catalysts). | Documenting the exact composition of a buffer solution or a reaction mixture. |

| NInChI [50] [53] | Nanomaterials & nanoforms | Core composition, size, shape, surface chemistry, and coating/ligands. | Differentiating between a 20nm spherical gold nanoparticle and a 40nm rod-shaped one for regulatory submission. |

Table 2: Quantifying the Impact of FAIR Data Implementation

| Benefit Category | Quantitative / Qualitative Impact | Evidence / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Cost of Non-FAIR Data | Estimated cost of not having FAIR research data in the EU is €10.2 billion per year due to inefficiency and duplication. | EU Report on 'Cost-benefit analysis for FAIR research data' [52] |

| Research Efficiency | ~80% of effort goes into data wrangling and preparation, leaving only 20% for effective research and analytics. | Industry Analysis [10] |

| Machine-Readiness | FAIR data enhances automated machine finding and use of data, which is a prerequisite for functional AI/ML applications in R&D. | Expert Analysis [54] [52] |

| Data Reproducibility | Well-documented data with rich metadata and unique identifiers (InChI) allows others to validate and replicate findings. | FAIR Guiding Principles [10] |

The IUPAC FAIRSpec project aims to promote the adoption of FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data management principles specifically for chemical spectroscopy. The core objective is to ensure that spectroscopic data collections are maintained in a form that allows critical metadata to be extracted, increasing the probability that data will be findable and reusable both during research and after publication [55] [56]. A "FAIRSpec-ready spectroscopic data collection" consists of instrument data, chemical structure representations, and related digital items organized for automatic or semi-automatic metadata extraction [56].

FAIR Data Principles in Chemistry

The FAIR principles provide a structured framework to manage the growing volume and complexity of chemical research data [17].

Table: The Core FAIR Principles for Chemistry Data

| Principle | Technical Definition | Chemistry Context & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Findable | Data and metadata have globally unique and persistent machine-readable identifiers. | Chemical structures with InChIs; datasets with DOIs [17]. |

| Accessible | Data and metadata are retrievable via their identifiers using a standardized protocol. | Data repositories using HTTP/HTTPS; metadata remains accessible even if data is restricted [17]. |