Virtual Screening in Drug Discovery: A 2025 Guide to Methods, Applications, and Best Practices

This article provides a comprehensive overview of virtual screening (VS) as a cornerstone computational technique in modern drug discovery.

Virtual Screening in Drug Discovery: A 2025 Guide to Methods, Applications, and Best Practices

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of virtual screening (VS) as a cornerstone computational technique in modern drug discovery. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of VS, detailing both ligand-based and structure-based methodologies. The scope extends to practical applications across pharmaceuticals, agriculture, and materials science, addressing common challenges in scoring functions, data management, and experimental validation. It further offers insights for troubleshooting and optimizing workflows and presents a comparative analysis of leading software tools. By synthesizing current trends, including the integration of AI and AlphaFold2-predicted structures, this guide serves as a strategic resource for leveraging VS to accelerate hit identification and reduce R&D costs.

What is Virtual Screening? Core Concepts Revolutionizing Drug Discovery

Virtual Screening (VS) is a computational methodology used in drug discovery to rapidly evaluate and prioritize large libraries of chemical compounds for their potential to bind to a biological target of interest [1]. It serves as a fast and cost-effective alternative or complement to experimental high-throughput screening (HTS), enabling researchers to focus synthesis and testing efforts on the most promising candidates [1]. By leveraging computational power, VS can explore vast chemical spaces, including ultra-large "make-on-demand" libraries containing billions of readily available compounds, far exceeding the capacity of physical screening methods [2] [3].

The primary purposes of virtual screening are library enrichment, where vast numbers of diverse compounds are screened to identify a subset with a higher proportion of actives, and compound design, which involves detailed analysis of smaller series to guide optimization through quantitative prediction of binding affinity [1]. As pharmaceutical research faces increasing pressure to improve efficiency and reduce costs, virtual screening has become an indispensable tool for modern drug discovery pipelines.

Core Methodologies in Virtual Screening

Virtual screening methodologies are broadly categorized into two complementary approaches: ligand-based and structure-based methods. Each offers distinct advantages and is often used in combination to maximize the effectiveness of the screening campaign [1].

Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS)

Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS) operates without requiring the 3D structure of the target protein [1]. Instead, it leverages knowledge from known active ligands to identify new hits that share similar structural or pharmacophoric features [1]. This approach is particularly valuable during early discovery stages when no protein structure is available or for prioritizing large chemical libraries quickly and cost-effectively [1].

Key LBVS methodologies include:

- Similarity Searching: Uses molecular fingerprints or descriptors to identify compounds structurally similar to known actives [4]

- Pharmacophore Modeling: Identifies compounds that can match the essential 3D arrangement of functional groups necessary for biological activity [1]

- Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling: Correlates molecular features or properties with biological activity using statistical methods [5]

Advanced LBVS platforms like eSim, ROCS, and FieldAlign automatically identify relevant similarity criteria to rank potentially active compounds, while more sophisticated methods like Quantitative Surface-field Analysis (QuanSA) construct physically interpretable binding-site models based on ligand structure and affinity data using multiple-instance machine learning [1].

Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS)

Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS) utilizes the three-dimensional structure of the target protein, typically obtained through X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM, or computational methods like homology modeling [1]. This approach provides atomic-level insights into protein-ligand interactions, including hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts, often yielding better enrichment for virtual libraries by incorporating explicit information about the binding pocket's shape and volume [1].

The cornerstone of SBVS is molecular docking, which involves:

- Pose Prediction: Placing candidate ligands into the target binding site in energetically favorable orientations [4]

- Scoring: Ranking poses based on predicted binding affinity using scoring functions [4]

While most docking methods excel at pose prediction, accurately ranking compounds by affinity remains challenging [1]. More computationally demanding methods like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) calculations represent the state-of-the-art for structure-based affinity prediction but are typically limited to small structural modifications around known reference compounds [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Virtual Screening Methodologies

| Feature | Ligand-Based VS | Structure-Based VS |

|---|---|---|

| Requirement | Known active ligands | Target protein structure |

| Computational Cost | Lower | Higher |

| Best Application | Early-stage discovery, large library prioritization | Structure-enabled discovery, binding mode analysis |

| Key Strengths | Fast pattern recognition, generalizes across chemistries | Atomic-level interaction insights, better enrichment |

| Common Tools | eSim, ROCS, FieldAlign, QuanSA | Molecular docking packages, FEP tools |

Quantitative Performance and Validation

The effectiveness of virtual screening is demonstrated through both individual case studies and large-scale validation campaigns. When applied to ultra-large libraries, VS has achieved remarkable success rates that often surpass traditional HTS.

In one prospective study screening a 140-million compound library for Cannabinoid Type II receptor (CB2) antagonists, researchers achieved an experimentally validated hit rate of 55% - substantially higher than typical HTS hit rates of 0.001-0.15% [3] [6]. This demonstrates VS's exceptional capability for library enrichment when applied to appropriately designed chemical spaces.

A comprehensive 318-target study evaluating the AtomNet convolutional neural network further validated computational screening at scale [6]. The system successfully identified novel hits across every major therapeutic area and protein class, with an average hit rate of 6.7% for internal projects and 7.6% for academic collaborations [6]. Importantly, this performance was achieved without manual cherry-picking of compounds and included success for targets without known binders or high-quality X-ray structures [6].

Table 2: Virtual Screening Performance Across Studies

| Study Description | Library Size | Experimental Hit Rate | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| CB2 Antagonist Discovery [3] | 140 million compounds | 55% | Structure-based screening identified high-affinity antagonists |

| Internal Portfolio Validation [6] | 16 billion compounds | 6.7% (average across 22 targets) | 91% of projects yielded confirmed hits; successful with homology models |

| Academic Collaboration Program [6] | 20 billion+ compounds | 7.6% (average across 296 targets) | Effective across all major therapeutic areas and protein families |

| REvoLd Algorithm Benchmark [2] | 20 billion+ compounds | 869-1622x enrichment over random | Evolutionary algorithm efficiently explored ultra-large chemical space |

Advanced algorithms like REvoLd (RosettaEvolutionaryLigand) demonstrate how specialized approaches can efficiently navigate ultra-large chemical spaces. In benchmarks across five drug targets, REvoLd achieved improvements in hit rates by factors between 869 and 1622 compared to random selections, while incorporating full ligand and receptor flexibility [2].

Integrated Protocols and Workflows

Successful virtual screening campaigns typically integrate multiple methodologies in structured workflows. Below are detailed protocols for representative screening approaches.

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Virtual Screening with Molecular Docking

Objective: Identify novel binders for a protein target with known 3D structure through molecular docking.

Materials:

- Target protein structure (PDB format)

- Chemical library (e.g., Enamine REAL, ZINC15)

- Docking software (e.g., AutoDock Vina, RosettaLigand)

- Computational resources (CPU/GPU clusters)

Procedure:

Protein Preparation

- Obtain crystal structure or homology model

- Add hydrogen atoms and optimize protonation states

- Remove water molecules except structurally important ones

- Generate multiple receptor conformations if accounting for flexibility [3]

Chemical Library Preparation

- Select library (e.g., make-on-demand combinatorial libraries) [3]

- Filter compounds based on drug-likeness (Lipinski's Rule of Five)

- Convert structures to 3D coordinates

- Generate tautomers and stereoisomers

Molecular Docking

- Define binding site coordinates based on known ligand or active site

- Set docking parameters (exhaustiveness, search space)

- Execute docking runs in parallel

- Score and rank compounds based on binding affinity

Post-Docking Analysis

- Visualize top-ranking poses

- Cluster compounds based on structural similarity

- Apply additional filters (interaction patterns, synthetic accessibility)

Experimental Validation

- Select diverse top-ranked compounds for synthesis or purchase

- Test binding or activity in biochemical assays

- Confirm dose-response for confirmed hits

Protocol 2: AI-Enhanced Hybrid Screening with VirtuDockDL

Objective: Leverage deep learning for enhanced virtual screening accuracy and efficiency.

Materials:

- Molecular dataset with activity annotations

- Target structure or known active ligands

- VirtuDockDL platform or similar AI tools

- RDKit or Open Babel for cheminformatics

- Python environment with PyTorch Geometric

Procedure:

Data Preprocessing

- Collect chemical structures and activity data from databases (ChEMBL, PubChem)

- Standardize structures and remove duplicates

- Convert SMILES to molecular graphs using RDKit [7]

- Split data into training/validation/test sets

Feature Extraction

- Calculate molecular descriptors (molecular weight, LogP, TPSA)

- Generate molecular fingerprints (ECFP, Morgan)

- Extract graph-based features (atom types, bond orders, spatial coordinates) [7]

Model Training

- Implement Graph Neural Network architecture with multiple custom layers

- Include batch normalization and residual connections

- Train model to predict biological activity from molecular features [7]

- Validate using cross-validation and external test sets

Virtual Screening

- Apply trained model to score large compound libraries

- Combine predictions with docking scores for hybrid approach

- Rank compounds by integrated scores

Experimental Validation

- Select top-ranking compounds for testing

- Validate hits in dose-response experiments

- Iterate based on new data to improve models

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful virtual screening relies on a comprehensive toolkit of computational resources, chemical libraries, and software solutions. The table below details key components essential for establishing an effective virtual screening pipeline.

Table 3: Virtual Screening Research Reagent Solutions

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Libraries | Enamine REAL, ZINC15, PubChem | Source of screening compounds; REAL offers billions of make-on-demand molecules [2] |

| Cheminformatics | RDKit, Open Babel, CDD Vault | Process chemical structures, calculate descriptors, manage screening data [4] [8] |

| Docking Software | AutoDock Vina, RosettaLigand, ICM-Pro | Predict protein-ligand binding modes and affinities [2] [3] |

| AI/ML Platforms | AtomNet, VirtuDockDL, DeepChem | Apply deep learning for enhanced prediction accuracy [7] [6] |

| Visualization & Analysis | CDD Visualization, ChemicalToolbox | Analyze screening results, visualize chemical space [4] [8] |

| Specialized Algorithms | REvoLd, Deep Docking, V-SYNTHES | Screen ultra-large libraries efficiently using evolutionary or active learning approaches [2] |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

Virtual screening continues to evolve rapidly, driven by advances in artificial intelligence, growth of chemical libraries, and improved computational resources. Several key trends are shaping the future of this field:

AI and Deep Learning Integration: Convolutional neural networks like AtomNet and graph neural networks as implemented in VirtuDockDL are demonstrating remarkable performance in large-scale empirical studies, achieving hit rates that substantially exceed traditional HTS while exploring broader chemical spaces [7] [6]. These systems can successfully identify novel scaffolds even for targets without known binders or high-quality structures [6].

Ultra-Large Library Screening: Make-on-demand combinatorial libraries now contain tens to hundreds of billions of readily available compounds, creating unprecedented opportunities for discovery [2] [3]. Specialized algorithms like REvoLd use evolutionary approaches to efficiently navigate these vast spaces without exhaustive enumeration, achieving enrichment factors of 869-1622x over random selection [2].

Hybrid Methodologies: Combining ligand- and structure-based approaches through sequential integration or parallel consensus screening yields more reliable results than either method alone [1]. Case studies demonstrate that hybrid models averaging predictions from both approaches can outperform individual methods through partial cancellation of errors [1].

As these trends continue, virtual screening is positioned to substantially replace HTS as the primary initial step in small-molecule drug discovery, offering unprecedented access to chemical space while reducing costs and timelines [6].

The traditional drug discovery and development process is a long, costly, and high-risk endeavor, typically requiring over 10–15 years and an average cost of $1–2 billion for each new approved drug [9]. A staggering 90% of clinical drug development fails, with about 40–50% of failures attributed to a lack of clinical efficacy and 30% to unmanageable toxicity [9]. In this challenging landscape, virtual screening (VS) has emerged as a transformative computational approach at the earliest stages of drug discovery. VS uses artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) to rapidly identify potential drug candidates by screening vast chemical libraries in silico, prioritizing the most promising compounds for synthesis and experimental testing. By leveraging structure-based or ligand-based design, VS addresses the core reasons for clinical failure early in the pipeline, offering a strategic avenue to significantly compress development timelines and reduce the immense costs associated with bringing a new drug to market.

Quantitative Impact: How VS Accelerates Timelines and Lowers Costs

Virtual screening drives efficiency by front-loading the critical filtering process, leading to substantial and measurable gains in both speed and cost.

Reduction in Preclinical Timelines

AI and VS platforms have demonstrated a remarkable ability to compress the early discovery and preclinical phases, which traditionally can take around five years. For instance, Insilico Medicine's AI-designed drug for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis progressed from target discovery to Phase I clinical trials in just 18 months [10]. Similarly, Exscientia has reported AI-driven design cycles that are approximately 70% faster than conventional methods [10]. This acceleration is largely achieved by intelligently minimizing the number of compounds that need to be synthesized and tested experimentally. In one case, Exscientia's CDK7 inhibitor program achieved a clinical candidate after synthesizing only 136 compounds, a small fraction of the thousands typically required in traditional medicinal chemistry workflows [10].

Direct Cost Savings in Compound Identification and Optimization

The efficiency gains of VS translate directly into significant cost savings. By performing screening computationally, researchers can evaluate millions to billions of compounds without the associated costs of chemical reagents, laboratory supplies, and equipment time [5] [11]. Furthermore, the "make-test-analyze" cycle in lead optimization is a major cost center. VS streamlines this by using predictive models to propose compounds with a higher probability of success, drastically reducing the number of iterative cycles needed. A self-learning digital twin of a biopharmaceutical manufacturing process, which integrates VS and process modeling, enabled a reduction of required experiments in process characterization by more than 50%, directly slashing a multi-million-dollar undertaking and shortening the time to market [12].

Table 1: Quantitative Benefits of Virtual Screening in Drug Discovery

| Metric | Traditional Approach | AI/VS-Enhanced Approach | Reported Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Clinical Candidate | ~5 years (preclinical) | As little as 18 months [10] | >50% reduction [12] [10] |

| Compounds Synthesized | Thousands | Hundreds (e.g., 136 for a CDK7 inhibitor) [10] | 10-fold reduction [10] |

| Experiment Reduction | N/A | Use of self-learning digital twins [12] | >50% reduction [12] |

| Design Cycle Speed | Baseline | AI-driven design cycles [10] | ~70% faster [10] |

Methodological Protocols: LBVS and SBVS in Practice

Virtual screening methodologies are broadly categorized into two paradigms, each with distinct protocols and applications.

Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS) Protocol

LBVS is employed when the 3D structure of the target protein is unknown but there are known active ligand(s). It operates on the principle that molecules with similar structures or properties are likely to have similar biological activities.

Protocol 1: 3D Similarity Screening with ROCS

- Aim: To identify novel active compounds based on 3D molecular shape and chemical feature similarity to a known active query ligand.

- Procedure:

- Query Definition: Select a known high-affinity ligand and generate a representative low-energy 3D conformation.

- Database Preparation: Prepare a database of small molecule structures in a suitable 3D format (e.g., SDF). Generate conformational ensembles for each molecule to account for flexibility.

- Molecular Superimposition: For each molecule in the database, the ROCS algorithm performs a rigid-body superimposition to find the optimal overlap with the query molecule's volume [11].

- Similarity Scoring: Calculate the Tanimoto Combo Score, which is a weighted sum of the Shape Tanimoto (Eq. 1) and the Color (chemical feature) Tanimoto scores [11]. Shape Tanimoto = Voverlap / (Vquery + Vdb - Voverlap) (Eq. 1) Where Voverlap is the shared volume, and Vquery and Vdb are the volumes of the query and database molecule, respectively.

- Hit Prioritization: Rank all database compounds by their similarity score. Compounds exceeding a predefined score threshold (e.g., Tanimoto Combo > 1.2) are selected as virtual hits for experimental validation.

Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS) Protocol

SBVS is used when a high-resolution 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., from X-ray crystallography or Cryo-EM) is available. It predicts the binding affinity and mode of ligands within a specific binding site.

Protocol 2: Molecular Docking with Glide or AutoDock

- Aim: To predict the binding pose and affinity of small molecules against a defined protein binding pocket.

- Procedure:

- Protein Preparation:

- Obtain the protein structure (e.g., from PDB database).

- Remove water molecules and co-crystallized ligands, unless critical for binding.

- Add hydrogen atoms, assign protonation states, and optimize side-chain conformations.

- Binding Site Grid Generation: Define the 3D spatial coordinates (a "grid") encompassing the binding pocket of interest.

- Ligand Library Preparation: Prepare the database of small molecules, generating 3D structures and likely tautomers and protonation states at physiological pH.

- Molecular Docking: For each ligand, the docking algorithm performs a conformational search to generate multiple putative binding poses within the defined grid.

- Scoring and Ranking: Each pose is scored using a scoring function (e.g., GlideScore, Vina) that estimates the binding free energy. Poses are ranked, and the best-scoring pose for each ligand is used to rank the entire library.

- Post-Docking Analysis: Visually inspect top-ranked complexes to assess pose rationality (e.g., key hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, salt bridges). Select top-ranked compounds with favorable interactions for experimental testing.

- Protein Preparation:

Virtual Screening Workflow Decision Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of virtual screening relies on a suite of computational tools and databases.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Virtual Screening

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function in VS |

|---|---|---|

| ROCS (Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures) [11] | Software | Performs 3D shape and chemical feature superposition for ligand-based screening. |

| Molecular Docking Software (e.g., Glide, AutoDock) [5] [11] | Software | Predicts the binding pose and affinity of a small molecule within a protein's binding site. |

| ZINC Database | Compound Library | A freely available database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. |

| ChEMBL Database | Bioactivity Database | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, used for model training and querying. |

| USRCAT (Ultrafast Shape Recognition) [11] | Software/Algorithm | An atomic distance-based method for fast 3D ligand similarity searching, incorporating pharmacophore features. |

| PL-PatchSurfer [11] | Software/Algorithm | A surface-based method that compares local physicochemical patches on molecular surfaces for LBVS. |

| Palicourein | Palicourein|Anti-HIV Cyclotide|Research Use Only | Palicourein is a macrocyclic peptide isolated fromPalicourea condensata. For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic, therapeutic, or personal use. |

| Amylin (8-37), rat | Amylin (8-37), rat, MF:C140H227N43O43, MW:3200.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

An Integrated Framework: The STAR Principle and VS

To maximize the impact of VS on reducing late-stage attrition, its results should be interpreted within a holistic pharmacological framework. The Structure–tissue exposure/selectivity–Activity Relationship (STAR) provides a powerful model for this. STAR posits that over-reliance on Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) alone—optimizing for potency and specificity—can overlook critical factors governing clinical efficacy and toxicity, namely a drug's distribution and accumulation in target versus normal tissues (Structure–tissue exposure/selectivity Relationship, or STR) [9]. VS can be strategically aligned with the STAR framework to select superior drug candidates early on. For example, VS filters can be designed to prioritize compounds not only with high predicted affinity for the target (Activity) but also with physicochemical properties predictive of favorable tissue distribution (tissue exposure/selectivity), thereby de-risking programs against future failures due to lack of efficacy or unmanageable toxicity [9].

Integrating VS with the STAR Framework

Virtual screening is no longer a supplementary tool but a central driver of efficiency in modern drug discovery. By leveraging advanced computational methods like AI-powered LBVS and SBVS, researchers can drastically shorten preclinical timelines, significantly reduce the costs of compound synthesis and testing, and—most importantly—make more informed decisions that de-risk the later, most expensive stages of clinical development. The integration of VS outputs into holistic frameworks like STAR ensures that candidate drugs are selected not only for their potency but also for properties that predict clinical success. As AI and computational power continue to advance, the role of VS in reducing time-to-market and cutting R&D costs is poised to become even more profound, heralding a new era of data-driven and efficient drug development.

Virtual screening (VS) is a cornerstone of modern computer-aided drug design (CADD), serving as a fast and cost-effective strategy to identify promising hit compounds from vast chemical libraries [1]. By computationally predicting the biological activity of compounds, VS dramatically reduces the synthesis and testing requirements, thereby accelerating the early drug discovery pipeline [1]. The two fundamental methodologies that underpin virtual screening are ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS) and structure-based virtual screening (SBVS). LBVS leverages knowledge from known active ligands, while SBVS relies on the three-dimensional structure of the biological target [1] [13]. The strategic selection and integration of these approaches are critical for successful hit identification and optimization, especially when navigating ultra-large chemical spaces containing billions of purchasable compounds [13]. This application note delineates the core principles, protocols, and synergistic combination of these two pillars, providing a structured framework for their application in contemporary drug discovery projects.

Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS): Principles and Protocols

LBVS methodologies do not require a target protein structure. Instead, they operate on the principle of "molecular similarity," which posits that structurally similar molecules are likely to exhibit similar biological activities [1] [13]. These approaches are exceptionally valuable during the early stages of discovery for prioritizing large chemical libraries and in situations where a high-quality protein structure is unavailable.

Core Methodologies and Workflows

- Pharmacophore Modeling: A pharmacophore represents the essential ensemble of steric and electronic features necessary for a molecule to interact with a biological target. LBVS methods can utilize predefined pharmacophores or employ modern tools like eSim, ROCS, and FieldAlign to automatically identify relevant similarity criteria for ranking compounds [1]. The workflow involves:

- Feature Identification: Analysis of known active ligands to define chemical features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, charged groups).

- Model Generation: Creating a 3D spatial query that embodies the relative arrangement of these features.

- Database Screening: Scanning compound libraries to identify molecules that match the pharmacophore model.

- Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR): QSAR models correlate quantitative molecular descriptors (e.g., lipophilicity, polar surface area, electronic properties) with biological activity using statistical or machine learning methods [13]. Advanced 3D-QSAR methods like Quantitative Surface-field Analysis (QuanSA) construct physically interpretable binding-site models from ligand structure and affinity data using multiple-instance machine learning, enabling predictions of both ligand binding pose and quantitative affinity across chemically diverse compounds [1].

- Similarity Searching: This approach uses one or more known active reference compounds to find similar molecules in a database. Common techniques involve:

- Molecular Fingerprints: Binary vectors representing the presence or absence of specific substructures or topological paths in a molecule (e.g., Extended-connectivity fingerprints). Similarity is calculated using metrics like the Tanimoto coefficient [13].

- Shape-Based Similarity: Tools like ROCS superimpose a candidate molecule onto a reference active to maximize 3D shape and chemical feature overlap, providing a score that ranks potential actives [1].

Application Protocol: LBVS for Hit Identification

Aim: To identify novel hit compounds for a target using known actives as a reference. Software Tools: BioSolveIT infiniSee, Pharmacelera exaScreen (for ultra-large libraries); OpenEye ROCS, Optibrium eSim, Cresset FieldAlign (for 3D similarity) [1]. Compound Libraries: ZINC, ChEMBL, in-house corporate libraries.

- Ligand Set Curation: Assemble and curate a set of known active ligands with robust activity data from literature or internal assays. This includes standardizing structures and enumerating plausible tautomers and protonation states [13].

- Model Development:

- For Pharmacophore Screening: Use multiple active ligands to generate a consensus pharmacophore model. Validate the model's ability to discriminate known actives from inactives in a test set.

- For QSAR: Calculate molecular descriptors for the training set of active and inactive compounds. Use machine learning algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, Deep Learning) to build a predictive classification or regression model [13].

- Virtual Screening Execution: Apply the generated model (pharmacophore, QSAR, or similarity query) to screen the target compound library.

- Hit Prioritization: Rank compounds based on their fit value (pharmacophore), predicted activity (QSAR), or similarity score. Apply additional filters for drug-likeness (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) and potential pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS).

Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS): Principles and Protocols

SBVS requires a 3D structure of the target protein, obtained through X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), or computational methods like homology modeling [1]. It provides atomic-level insights into protein-ligand interactions, often leading to better library enrichment by explicitly considering the shape and properties of the binding pocket [1].

Core Methodologies and Workflows

- Molecular Docking: This is the most common SBVS approach, involving two main steps:

- Pose Generation: Sampling possible orientations (poses) of the ligand within the defined binding site.

- Scoring: Ranking the generated poses using a scoring function to estimate binding affinity. While docking excels at pose prediction, accurately predicting absolute binding affinity remains a challenge [1]. Popular tools include AutoDock Vina, Glide, and FRED [14] [15].

- Free Energy Perturbation (FEP): FEP calculations represent the state-of-the-art for structure-based affinity prediction, offering high accuracy. However, they are computationally very demanding and are typically reserved for lead optimization, focusing on small structural modifications around known compounds [1].

- Machine Learning-Enhanced Docking: Recent advancements integrate deep learning to improve scoring functions. Platforms like HelixVS and RosettaVS use multi-stage screening: initial docking with classical tools (e.g., Vina) is followed by re-scoring of top poses with a deep learning model, significantly improving enrichment and speed [14] [16]. Similarly, re-scoring docking outputs with pretrained ML scoring functions like CNN-Score has been shown to consistently augment SBVS performance [15].

Application Protocol: SBVS Using Molecular Docking

Aim: To identify hit compounds by predicting their binding mode and affinity within a target's binding pocket. Software Tools: AutoDock Vina, FRED, PLANTS, Schrödinger Glide, RosettaVS, HelixVS [14] [15] [16]. Required Structures: Target protein structure (PDB format) and a prepared compound library.

- Protein Preparation:

- Obtain a high-resolution structure from the PDB or generate a homology model. AlphaFold models can be used but may require refinement of side chains and flexible loops for reliable docking [1].

- Remove water molecules and cofactors, add hydrogen atoms, and assign correct protonation states to residues (e.g., His, Asp, Glu) using tools like OpenEye's "Make Receptor" [15].

- Ligand Library Preparation: Prepare the small molecule library by generating 3D conformations, likely tautomers, and protonation states at biological pH (e.g., using Omega software) [15]. Convert the library into the appropriate format for docking (e.g., PDBQT, mol2).

- Binding Site Definition and Docking Grid Setup: Define the coordinates and dimensions of the binding site of interest. The grid box should be large enough to accommodate flexible ligands.

- Docking and Re-scoring Execution:

- Run the docking simulation to generate multiple poses per ligand.

- For ML-enhanced workflows, the top poses from the initial docking are fed into a deep learning-based affinity scoring model (e.g., based on RTMscore in HelixVS) for more accurate ranking [14].

- Pose Analysis and Hit Selection: Manually inspect the top-ranked poses for sensible interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, pi-stacking). Prioritize compounds with strong predicted affinity and favorable interaction geometries.

Integrated Approaches: Combining LBVS and SBVS

Evidence strongly supports that hybrid approaches, which combine the atomic-level insights from SBVS with the pattern recognition capabilities of LBVS, outperform individual methods by reducing prediction errors and increasing confidence in hit identification [1] [13]. The integration can be achieved through sequential, parallel, or hybrid frameworks.

Strategy Comparison and Selection Framework

The choice of integration strategy depends on project goals, available data, and computational resources. The following table outlines the primary combined strategies.

Table 1: Strategies for Combining LBVS and SBVS Approaches

| Strategy | Description | Workflow | Advantages | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential Combination | A funnel strategy where one method is used to filter a library before applying the second method [13]. | LBVS (e.g., pharmacophore) → SBVS (e.g., docking) | Computationally economical; conserves expensive SBVS for a small, pre-enriched set [1]. | Rapidly narrowing down ultra-large libraries (>1 billion compounds) [13]. |

| Parallel Combination | LBVS and SBVS are run independently on the same library, and results are fused post-screening [1] [13]. | LBVS & SBVS run simultaneously → Results fusion via data fusion algorithms (e.g., rank-based, machine learning) | Increases the likelihood of recovering potential actives; mitigates limitations inherent in each method [1]. | Broad hit identification to prevent missed opportunities when resources allow for testing more compounds [1]. |

| Hybrid (Consensus) Scoring | Creates a single unified ranking by combining scores from both LBVS and SBVS into a consensus model [1]. | Scores from LBVS & SBVS → Combined via multiplicative or averaging strategies | Reduces false positives; increases confidence by favoring compounds that rank highly across both methods [1]. | When a high-confidence, shortlist of candidates is required for experimental testing [1]. |

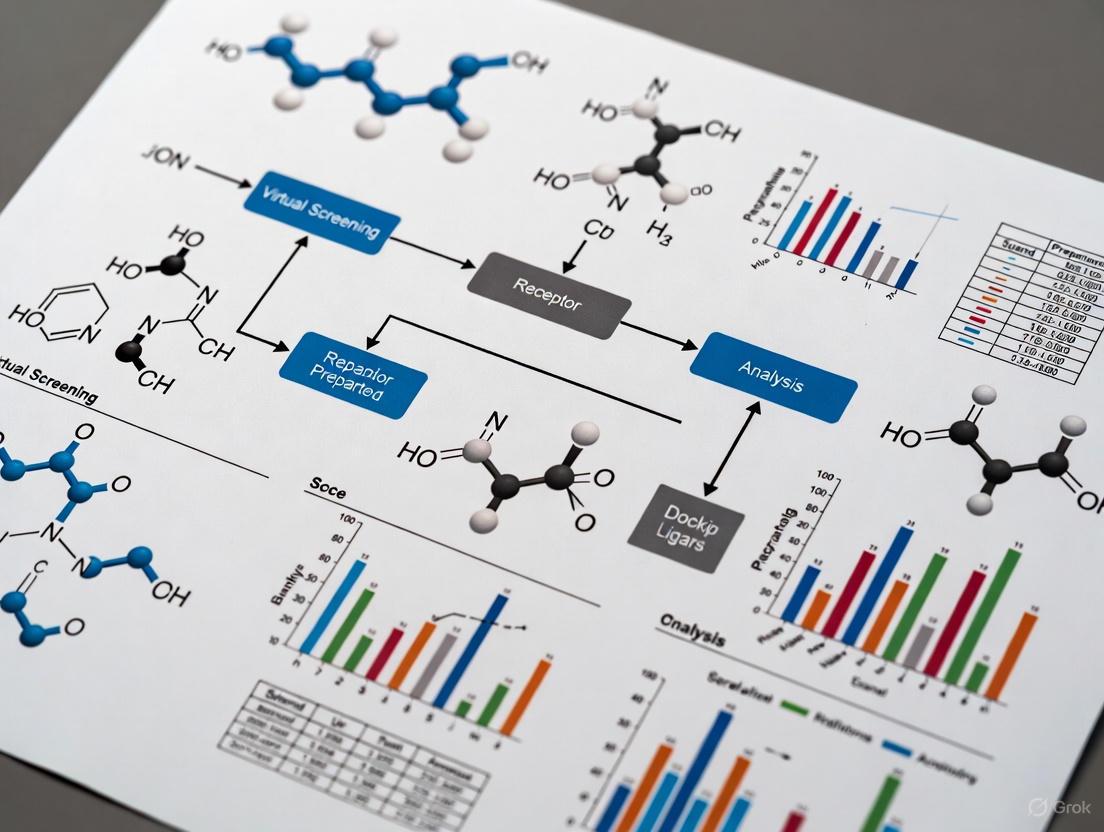

Workflow Visualization: Integrated VS Strategy

The following diagram illustrates a robust integrated virtual screening workflow that combines ligand-based and structure-based methods.

Performance Benchmarking and Practical Considerations

Quantitative Performance of VS Methods

Benchmarking on standard datasets like DUD-E allows for a quantitative comparison of virtual screening methods. Performance is often measured by the Enrichment Factor (EF), which indicates how much a method enriches the top-ranked list with true active compounds compared to a random selection.

Table 2: Virtual Screening Performance Benchmarks

| Method / Platform | Key Features | Reported EFâ‚% (Top 1%) | Screening Speed | Reference / Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Classic physics-based docking | 10.0 | ~300 molecules/core/day | DUD-E [14] |

| Glide SP | Commercial, high-performance docking | 24.3 | ~2,400 molecules/core/day | DUD-E [14] |

| HelixVS | Multi-stage (Vina + Deep Learning re-scoring) | 27.0 | >10 million molecules/day (cluster) | DUD-E [14] |

| RosettaVS | Physics-based with receptor flexibility | 16.7 (Screening Power) | High (with active learning) | CASF-2016 [16] |

| Re-scoring (CNN-Score) | ML re-scoring of docking outputs | 28.0 - 31.0 | Fast re-scoring step | DEKOIS 2.0 (PfDHFR) [15] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

A successful virtual screening campaign relies on a suite of computational tools and databases.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Virtual Screening

| Category | Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example Tools / Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | Ultra-large Synthesizable Libraries | Provide billions of purchasable compounds for screening. | Enamine REAL, ZINC [13] |

| Curated Bioactive Libraries | Source of known active ligands for LBVS model building and validation. | ChEMBL, BindingDB [15] | |

| Software & Algorithms | LBVS Tools | Perform similarity searching, pharmacophore mapping, and QSAR modeling. | ROCS, QuanSA, eSim [1] |

| SBVS Tools | Perform molecular docking, pose generation, and scoring. | AutoDock Vina, FRED, PLANTS [15] | |

| ML/AI Platforms | Enhance scoring accuracy and screening speed through deep learning. | HelixVS, RosettaVS, CNN-Score [14] [15] [16] | |

| Data & Infrastructure | Protein Structure Databases | Source of experimental and predicted protein structures for SBVS. | PDB, AlphaFold Protein Structure Database [1] [17] |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Provides the computational power required for screening ultra-large libraries. | CPU/GPU Clusters, Cloud Computing [14] [16] | |

| Vasicine hydrochloride | Vasicine hydrochloride, CAS:7174-27-8, MF:C11H13ClN2O, MW:224.68 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Ethyl 2-(dimethylamino)benzoate | Ethyl 2-(dimethylamino)benzoate | CAS 55426-74-9 | High-purity Ethyl 2-(dimethylamino)benzoate for research. CAS 55426-74-9, Molecular Weight: 193.24. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Ligand-based and structure-based virtual screening represent the two foundational pillars of modern computational hit identification. LBVS offers speed and efficiency, particularly when structural data is limited, while SBVS provides detailed mechanistic insights and often superior enrichment [1]. The emergence of high-quality predicted protein structures from AlphaFold and the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence are profoundly impacting the field. AI-enhanced platforms like HelixVS and RosettaVS demonstrate that integrating deep learning with physics-based methods significantly boosts both the accuracy and throughput of virtual screening [14] [16]. Furthermore, the application of these hybrid strategies is expanding into novel territories, such as RNA-targeted drug discovery, as evidenced by tools like RNAmigos2 [17]. For researchers, the most effective strategy is rarely the exclusive use of one approach. Instead, a thoughtful combination of LBVS and SBVS, tailored to the available data and project objectives, provides the most robust and reliable path to identifying novel, promising drug candidates.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The following table details key reagents, software tools, and data resources essential for the preparation of compound libraries in virtual screening.

| Item Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in Library Preparation |

|---|---|---|

| ZINC Database [18] | Compound Database | A publicly accessible repository hosting chemical and structural information for millions of commercially available compounds; the primary source for building initial compound libraries. |

| FDA-Approved Drug Catalog (ZINC) [18] | Specialized Library | A curated collection within ZINC containing compounds approved by the FDA; essential for drug repurposing studies and high-priority screening. |

| Open Babel [18] | Bioinformatics Tool | Used for chemical file format conversion and energy minimization of small molecules, preparing them for docking. |

| AutoDockTools (MGLTools) [18] | Docking Software Utility | Provides scripts for preparing receptor and ligand files, specifically converting them to the PDBQT format required by docking tools like Vina. |

| jamlib Script (jamdock-suite) [18] | Automation Script | A customized computational program that automates the generation of energy-minimized, PDBQT-format compound libraries from sources like the ZINC database. |

| fpocket [18] | Bioinformatics Software | An open-source tool for ligand-binding pocket detection and characterization on the receptor; aids in defining the docking grid box. |

Experimental Protocols for Library Preparation and Standardization

Protocol 1: Generating a Standardized Compound Library from ZINC

This protocol details the steps to create a screening-ready library of compounds in the correct format for computational docking [18].

- Objective: To download, curate, and convert a set of compounds from the ZINC database into a library of energy-minimized 3D structures in PDBQT format.

- Principle: Raw compound data from public databases is often not in a ready-to-dock format. This process involves format standardization, structural optimization (energy minimization), and configuration for specific docking software.

- Materials & Reagents: ZINC database access, Unix-like system (or WSL on Windows), Open Babel, jamdock-suite scripts (e.g.,

jamlib). - Procedure:

- Compound Sourcing: Identify and download the desired compound set (e.g., FDA-approved drugs, a specific molecular weight range) from the ZINC database or files.docking.org [18].

- Format Conversion and Minimization: Use a tool like

jamlibor Open Babel to convert the downloaded structures into a consistent format and perform energy minimization to ensure physiologically relevant 3D conformations. - PDBQT Generation: Execute the

jamlibscript to automatically process the minimized structures and output the final library in PDBQT format, compatible with AutoDock Vina and related tools [18].

- Quantitative Standards: The success of the library preparation is measured by the successful conversion of 100% of the targeted compound list into valid, minimized PDBQT files, with no structural errors that would halt the docking process.

Protocol 2: Receptor and Binding Site Preparation

This protocol describes the setup of the protein target for docking, a critical step that defines the spatial region for screening.

- Objective: To prepare the receptor structure file and define the precise coordinates of the docking grid box.

- Principle: The receptor, typically from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), must be processed for docking. Identifying the binding pocket is crucial for focusing the screening and improving its efficiency and accuracy.

- Materials & Reagents: Receptor PDB file, AutoDockTools (MGLTools), fpocket software,

jamreceptorscript. - Procedure:

- Receptor Preparation: Clean the PDB file by removing water molecules and heteroatoms, adding polar hydrogens, and assigning partial charges. This can be done using AutoDockTools or an automated script like

jamreceptorto convert the file to PDBQT format [18]. - Pocket Detection: Run fpocket on the prepared receptor structure to identify and characterize potential ligand-binding cavities. fpocket will provide a list of pockets with associated druggability scores [18].

- Grid Box Definition: Select the primary binding pocket of interest from the fpocket results. The script

jamreceptorcan use this selection to automatically define the center and dimensions (size) of the grid box for docking [18].

- Receptor Preparation: Clean the PDB file by removing water molecules and heteroatoms, adding polar hydrogens, and assigning partial charges. This can be done using AutoDockTools or an automated script like

- Quantitative Standards: The grid box should be sized to fully encompass the binding pocket of interest, typically extending at least 5-10 Ã… beyond the known bounds of any co-crystallized ligand to allow for ligand flexibility.

Workflow Visualization

From Compound Source to Screening Library

Receptor Setup and Grid Definition

Integrated Pre-Screening Workflow

The Expanding Role of VS in Precision Medicine and Sustainable Agrochemicals

Virtual screening (VS) has emerged as a transformative tool in early-stage discovery, leveraging computational power to identify potential drug candidates from vast chemical libraries. By applying artificial intelligence (AI) and molecular modeling, VS streamlines the process of sifting through millions of compounds, predicting those with the highest likelihood of biological activity against a specific target [5]. This document provides detailed Application Notes and experimental Protocols to illustrate the expanding utility of VS in two critical fields: precision medicine, where therapies are tailored to individual patient genetics, and sustainable agrochemicals, which aim to develop effective crop protection agents with minimal environmental impact. The content is framed within a broader thesis on advancing virtual screening methodologies for more efficient and targeted candidate identification.

Application Notes: Comparative Analysis Across Domains

The application of VS differs in its target priorities and success metrics between precision medicine and agrochemical discovery. The table below summarizes key quantitative data and objectives from prospective studies in both fields.

Table 1: Comparison of Virtual Screening Applications in Precision Medicine and Sustainable Agrochemicals

| Feature | Application in Precision Medicine | Application in Sustainable Agrochemicals |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Identify patient-specific therapeutics; drug repurposing based on genomic data [19] | Discover species-specific pesticides; reduce environmental toxicity [19] |

| Representative Target | β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR), SARS-CoV-2 proteins, mutant kinases [19] | Allatostatin type-C receptor (AlstR-C) in pests, 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase [19] |

| Key VS Methodology | Evidential Deep Learning (EviDTI), active learning frameworks, sequence-to-drug design [19] | Structure-based docking on vast fragment libraries, AI-accelerated platforms like RosettaVS [19] |

| Reported Performance Gain | Active learning frameworks enabled resource-efficient identification from ultra-large libraries [19] | AI-accelerated docking (RNAmigos2) reported a 10,000x speedup in screening [19] |

| Experimental Validation | Identification of tyrosine kinase modulators; compounds against Staphylococcus aureus [19] | Validation of a specific AlstR-C agonist showing no harm to non-target insects [19] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: AI-Accelerated Virtual Screening for a Novel Therapeutic Target

This protocol details a structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) workflow enhanced by active learning, suitable for identifying hits against a protein target in drug discovery [5] [19].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for AI-Accelerated Virtual Screening

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Target Protein Structure | A 3D atomic-resolution structure (e.g., from X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM, or homology modeling) required for molecular docking. |

| Chemical Library | A digital library of small molecule compounds (e.g., ZINC, Enamine REAL) for screening. Billions of compounds may be used. |

| Molecular Docking Software | Software (e.g., AutoDock Vina, Glide, DOCK) that predicts how a small molecule binds to the target's active site. |

| AI/Active Learning Platform | A computational framework (e.g., RosettaVS, other active learning setups) that iteratively selects the most promising compounds for docking based on previous results, optimizing computational resources [19]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential for the computationally intensive tasks of docking millions of molecules and running AI models. |

II. Step-by-Step Methodology

Target Preparation:

- Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., β2AR).

- Using molecular modeling software, prepare the protein by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning correct protonation states, and optimizing side-chain orientations.

- Define the binding site coordinates based on known ligand interactions or predicted allosteric sites.

Library Curation and Preparation:

- Select an appropriate chemical library (e.g., a multi-billion compound library).

- Prepare all library compounds by generating 3D conformations, optimizing geometry, and assigning correct charges.

AI-Driven Docking Cascade:

- Initial Sampling: Perform molecular docking on a diverse, representative subset of the entire library (e.g., 0.1%).

- Model Training: Use the docking scores from this initial set to train an AI model (e.g., a regression model) to predict the docking scores of the remaining compounds.

- Iterative Screening: The active learning algorithm selects subsequent batches of compounds for docking based on the model's predictions, focusing on regions of chemical space predicted to have high affinity.

- Convergence: Repeat until a pre-defined number of top-ranking compounds is identified (e.g., 1,000 hits) or the model's predictions stabilize.

Post-Screening Analysis:

- Visually inspect the predicted binding poses of the top-ranked hits.

- Cluster the hits based on chemical structure to prioritize diverse scaffolds.

- Select a final shortlist (50-100 compounds) for in vitro experimental validation.

The workflow for this protocol is outlined in the diagram below.

Protocol 2: Species-Specific Agrochemical Lead Identification

This protocol describes a ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS) approach to discover agents that selectively target a pest-specific protein, minimizing harm to non-target organisms [19].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Species-Specific Agrochemical Screening

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Active Compound(s) against Target Pest | Known active molecule(s) targeting the pest protein of interest (e.g., a known AlstR-C ligand). Serves as the reference for similarity searching. |

| Agrochemical Compound Library | A specialized digital library containing known pesticides, bioactive molecules, and diverse chemical fragments relevant to agrochemistry. |

| Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Model | A machine learning model that correlates chemical structure features with biological activity for the target [5]. |

| Target Species Protein Model & Non-Target Orthologs | Protein structures or models for both the target pest (e.g., T.pityocampa AlstR-C) and related non-target species (e.g., bees) for selectivity analysis. |

II. Step-by-Step Methodology

Reference Ligand and Library Curation:

- Identify one or more known active compounds against the target pest protein.

- Prepare a focused agrochemical library for screening.

Ligand-Based Similarity Screening:

- Calculate molecular descriptors or fingerprints for the reference ligand and all compounds in the library.

- Perform a similarity search (e.g., using Tanimoto coefficient) to identify compounds structurally related to the active reference.

- Select the top several thousand similar compounds for further analysis.

Predictive QSAR Modeling:

- If a dataset of active and inactive compounds is available, train a QSAR classification or regression model [5].

- Use the trained model to predict the activity of the compounds shortlisted from the similarity search.

- Rank the compounds based on their predicted activity.

Selectivity Assessment (In silico):

- Perform molecular docking of the top-ranked compounds against the protein models of both the target pest and non-target organisms.

- Prioritize compounds that show strong predicted binding to the pest protein but weak binding to the non-target orthologs.

Hit Selection:

- Select a final shortlist of compounds (20-50) that are predicted to be potent and selective for in vivo validation in pest control assays.

The workflow for this protocol is outlined in the diagram below.

Virtual Screening in Action: A Deep Dive into Methods and Real-World Applications

In the pursuit of novel therapeutic agents, virtual screening stands as a cornerstone of modern computer-aided drug design (CADD), enabling the rapid evaluation of vast chemical libraries to identify promising drug candidates. Within this domain, ligand-based virtual screening techniques provide powerful computational strategies for lead identification and optimization when the three-dimensional structure of the biological target is unavailable or uncertain. These methods operate on the fundamental principle that molecules with similar structural or physicochemical characteristics are likely to exhibit similar biological activities. Among the most established and widely used ligand-based approaches are pharmacophore modeling, quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) analysis, and shape-based screening. These methodologies leverage known active compounds to discover new chemical entities with enhanced properties, effectively guiding the drug discovery process toward candidates with higher probability of success in experimental validation. This article details the core concepts, experimental protocols, and practical applications of these indispensable techniques, providing researchers with structured frameworks for their implementation in virtual screening campaigns.

Pharmacophore Modeling

Conceptual Foundation

A pharmacophore is defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [20] [21]. In essence, it is an abstract representation of molecular interactions, detached from specific chemical scaffolds, that captures the essential components for biological activity. The pharmacophore concept dates back to Paul Ehrlich in 1909, who initially described it as "a molecular framework that carries the essential features responsible for a drug's biological activity" [20]. Modern computational implementations represent pharmacophores as three-dimensional arrangements of chemical features including hydrogen bond donors, hydrogen bond acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, and ionizable groups, often supplemented with exclusion volumes to represent steric constraints of the binding site [21].

Generation Methodologies

Pharmacophore model generation typically follows one of two principal approaches, depending on available input data:

- Ligand-Based Modeling: This approach requires a set of known active compounds that bind to the same target site. The process involves conformational analysis of each molecule, molecular alignment to identify common spatial arrangements, and extraction of shared chemical features [20] [22]. Successful implementation necessitates structurally diverse training compounds with confirmed biological activity and common binding mode.

- Structure-Based Modeling: When a 3D structure of the target protein (often in complex with a ligand) is available, structure-based pharmacophores can be derived by analyzing interaction patterns in the binding site. Tools like LigandScout and Discovery Studio can automatically identify potential interaction points and generate feature-based pharmacophore hypotheses [22] [23].

Table 1: Common Pharmacophore Features and Their Characteristics

| Feature Type | Geometric Representation | Interaction Type | Structural Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | Vector or Sphere | Hydrogen Bonding | Amines, Carboxylates, Ketones, Alcoholes |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | Vector or Sphere | Hydrogen Bonding | Amines, Amides, Alcoholes |

| Hydrophobic | Sphere | Hydrophobic Contact | Alkyl Groups, Alicycles, non-polar aromatic rings |

| Aromatic | Plane or Sphere | π-Stacking, Cation-π | Any aromatic ring system |

| Positive Ionizable | Sphere | Ionic, Cation-Ï€ | Ammonium Ions, Metal Cations |

| Negative Ionizable | Sphere | Ionic | Carboxylates, Phosphates |

Application Protocol: Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for pharmacophore-based virtual screening:

Step 1: Model Generation

- For ligand-based approaches: Select 3-10 known active compounds with structural diversity and confirmed activity data. Generate conformational ensembles using tools such as CAESAR or Cyndi [20].

- For structure-based approaches: Obtain protein-ligand complex from PDB. Use software like LigandScout to identify interaction features and create initial hypothesis [23].

- Define pharmacophore features (HBA, HBD, hydrophobic, aromatic, ionizable) and their spatial tolerances.

- Incorporate exclusion volumes based on binding site topography to account for steric hindrance [21].

Step 2: Model Validation

- Validate model quality using known active and inactive compounds/decoys.

- Calculate enrichment metrics including AUC-ROC, enrichment factor (EF), and goodness-of-hit score [22] [23].

- A validated model should achieve EF(1%) > 10 and AUC > 0.7-0.8, with higher values indicating better performance [23].

Step 3: Database Screening

- Prepare screening database in appropriate 3D format with conformational expansion.

- Screen database using the validated pharmacophore model as a query.

- Apply exclusion volume constraints to eliminate compounds with steric clashes.

- Retrieve compounds that match the pharmacophore features within defined spatial tolerances.

Step 4: Post-Screening Analysis

- Visually inspect top-ranking hits to verify feature matching.

- Cluster results by chemical scaffold to ensure structural diversity.

- Subject filtered hits to molecular docking (if protein structure available) and ADMET prediction.

- Select final compounds for experimental validation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling and Screening

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Software | Structure & ligand-based pharmacophore modeling | Virtual screening, binding mode analysis [23] |

| Phase | Software | Pharmacophore perception, 3D QSAR, database screening | Ligand-based design, scaffold hopping [20] |

| Catalyst/HypoGen | Software | Automated pharmacophore generation | Quantitative pharmacophore modeling [20] |

| ZINC Database | Compound Library | Commercially available compounds for screening | Virtual screening hit identification [23] |

| DUD-E | Database | Curated decoys for validation | Pharmacophore model validation [22] |

| ChEMBL | Database | Bioactivity data | Training set compilation [22] |

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR)

Theoretical Principles

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a computational framework that predicts biological activity or physicochemical properties of molecules directly from their structural descriptors [24]. The fundamental hypothesis underpinning QSAR is that a quantifiable relationship exists between molecular structure and biological activity, allowing for the prediction of compound properties without the need for exhaustive experimental testing. Modern QSAR extends beyond traditional regression models to incorporate sophisticated machine learning algorithms and multidimensional molecular descriptors [25].

Modeling Workflow and Protocol

Step 1: Data Set Curation

- Collect compounds with consistent, high-quality biological activity data (e.g., IC50, Ki).

- Ensure structural diversity while maintaining mechanism consistency.

- Divide data into training (70-80%), validation (10-15%), and test sets (10-15%) using rational splitting methods.

Step 2: Molecular Descriptor Calculation

- Compute molecular descriptors using tools like Dragon, RDKit, or PaDEL.

- Include 1D (molecular weight, logP), 2D (topological indices, connectivity), and 3D descriptors (steric, electrostatic) when applicable [25] [24].

- Consider fingerprint representations (ECFP, MACCS) for structural similarity assessment.

Step 3: Feature Selection

- Apply variance thresholding to remove low-variance descriptors.

- Use correlation analysis to eliminate highly correlated descriptors.

- Implement advanced selection methods (Random Forest importance, LASSO regularization) to identify most relevant descriptors [24].

Step 4: Model Construction

- Select appropriate algorithm based on data size and complexity:

- Optimize hyperparameters through cross-validation.

Step 5: Model Validation

- Assess internal performance using k-fold cross-validation (typically 5-10 folds).

- Evaluate external predictivity using the held-out test set.

- Report standard metrics: R², Q², RMSE for regression; AUC, accuracy for classification.

- Apply Y-randomization to confirm model robustness [25].

Step 6: Model Interpretation and Application

- Analyze descriptor contributions to identify structural determinants of activity.

- Define applicability domain to establish model boundaries.

- Use model to predict activity of new compounds and prioritize synthesis or acquisition.

Table 3: QSAR Model Performance Benchmarks Across Algorithms

| Model Type | Typical R² Range | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Linear Regression | 0.6-0.8 | Small datasets, interpretability | Limited to linear relationships |

| Partial Least Squares | 0.65-0.85 | Collinear descriptors | Interpretation complexity |

| Random Forest | 0.7-0.9 | Complex nonlinear relationships | Potential overfitting |

| Support Vector Machines | 0.75-0.9 | High-dimensional data | Parameter sensitivity |

| Deep Neural Networks | 0.8-0.95 | Large, complex datasets | High computational demand, data hunger |

Shape-Based Screening

Fundamental Concepts

Shape-based screening methodologies operate on the principle that molecular shape complementarity is a primary determinant of biological activity, particularly when compounds interact with the same binding site. These approaches use the three-dimensional shape of known active molecules as templates to identify structurally diverse compounds with similar shape properties, facilitating scaffold hopping and lead diversification [26]. The basic similarity metric quantifies volume overlap between molecules, typically normalized to produce scores ranging from 0 (no overlap) to 1 (perfect overlap) [26].

Implementation Protocol

Step 1: Template Selection and Preparation

- Select a known active compound with demonstrated biological potency as the shape template.

- Generate a representative conformational ensemble of the template molecule.

- For rigid templates, a single low-energy conformation may suffice; flexible templates require multiple conformations.

Step 2: Shape Model Definition

- Choose appropriate shape representation:

- Pure shape (no chemical matching)

- Atom-typed shape (element-specific or pharmacophore-featured)

- Hybrid approaches combining shape and chemical features [26]

- Define scoring function (e.g., volume overlap, color atoms).

Step 3: Database Preparation

- Prepare screening database in 3D format with appropriate conformational sampling.

- Ensure chemical diversity in the database to maximize scaffold hopping potential.

Step 4: Shape Screening Execution

- Align each database molecule to the template using shape-matching algorithms.

- Calculate shape similarity scores for aligned conformations.

- Rank compounds by similarity score and apply threshold cutoffs (typically >0.7-0.8).

Step 5: Result Analysis and Hit Selection

- Visually inspect top-ranking hits to verify shape complementarity.

- Analyze chemical diversity of hits to identify novel scaffolds.

- Integrate with other filters (drug-likeness, synthetic accessibility).

- Select compounds for experimental validation.

Performance Considerations

Shape-based screening performance varies significantly based on the target and screening strategy. Incorporating chemical feature constraints ("color atoms") generally improves enrichment over pure shape approaches. As demonstrated in benchmark studies, pharmacophore-enhanced shape screening achieved average enrichment factors of 33.2 at 1% recovery, substantially outperforming pure shape (11.9) and atom-typed (15.6-20.0) approaches [26].

Table 4: Shape Screening Performance Across Targets (Enrichment Factors at 1%)

| Target | Pure Shape | Element-Based | Pharmacophore-Enhanced |

|---|---|---|---|

| CA | 10.0 | 27.5 | 32.5 |

| CDK2 | 16.9 | 20.8 | 19.5 |

| COX2 | 21.4 | 16.7 | 21.0 |

| DHFR | 7.7 | 11.5 | 80.8 |

| ER | 9.5 | 17.6 | 28.4 |

| Neuraminidase | 16.7 | 16.7 | 25.0 |

| Thrombin | 1.5 | 4.5 | 28.0 |

| Average | 11.9 | 17.0 | 33.2 |

Integrated Applications in Drug Discovery

Case Study: Identification of Natural Anti-Cancer Agents

In a comprehensive study targeting XIAP protein for cancer therapy, researchers implemented an integrated virtual screening approach combining structure-based pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking, and ADMET profiling [23]. The pharmacophore model was generated from a protein-ligand complex and validated with excellent discrimination capability (AUC = 0.98, EF1% = 10.0). Screening of natural product databases followed by molecular dynamics simulations identified three stable compounds with promising binding characteristics, demonstrating the power of integrated computational approaches for identifying novel therapeutic agents from natural sources.

Case Study: KHK-C Inhibitors for Metabolic Disorders

A recent campaign to identify novel ketohexokinase-C (KHK-C) inhibitors employed pharmacophore-based virtual screening of 460,000 compounds from the National Cancer Institute library [27]. Multi-level molecular docking, binding free energy estimation, and ADMET profiling identified compounds with superior docking scores (-7.79 to -9.10 kcal/mol) and binding free energies (-57.06 to -70.69 kcal/mol) compared to clinical candidates. Molecular dynamics simulations further refined the selection to the most stable candidate, highlighting the utility of sequential virtual screening filters for lead identification.

Protocol for Integrated Virtual Screening

Phase 1: Preliminary Screening

- Apply rapid filters (drug-likeness, functional groups) to reduce database size.

- Execute parallel screening using pharmacophore and shape-based methods.

- Select compounds passing either method for subsequent analysis.

Phase 2: Refined Screening

- Subject preliminary hits to QSAR prediction for activity estimation.

- Perform molecular docking to assess binding mode and complementarity.

- Apply more stringent ADMET filters based on predicted properties.

Phase 3: Final Selection

- Conduct binding free energy calculations (MM-GBSA/PBSA) for top candidates.

- Perform molecular dynamics simulations to assess complex stability.

- Select 10-20 diverse compounds for experimental validation.

Ligand-based virtual screening techniques, including pharmacophore modeling, QSAR analysis, and shape-based screening, provide powerful computational frameworks for efficient drug candidate identification. These methods leverage existing structure-activity knowledge to guide the discovery of novel bioactive compounds, significantly reducing the time and resources required for lead identification. When implemented using the detailed protocols provided in this article and integrated with complementary structure-based approaches, these techniques form a comprehensive strategy for modern drug discovery. As computational power continues to grow and algorithms become increasingly sophisticated, the accuracy and applicability of these ligand-based methods will further expand, solidifying their role as indispensable tools in the medicinal chemist's arsenal.

Structure-based computational techniques have become indispensable in modern drug discovery, dramatically reducing the time and resources required to identify viable therapeutic candidates [28]. These methods leverage the three-dimensional structures of biological targets to predict how small molecules (ligands) will interact with them. Molecular docking predicts the preferred orientation of a ligand within a target binding site, while molecular dynamics (MD) simulations explore the stability and dynamic behavior of the resulting complex over time [29] [30]. When integrated into a virtual screening pipeline, these tools enable researchers to rapidly prioritize the most promising compounds from libraries containing thousands to millions of molecules for further experimental validation, thereby streamlining the path from target identification to lead candidate [28].

Integrated Computational Workflow for Virtual Screening

The application of molecular docking and MD simulations is typically embedded within a broader, multi-step computational workflow designed to efficiently sift through vast chemical spaces. The diagram below illustrates a generalized protocol for structure-based virtual screening.

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

Protocol: Structure-Based Virtual Screening

This protocol outlines the steps for screening a natural compound library to identify inhibitors targeting a specific binding site [29] [30].

3.1.1. Target Protein Preparation

- Objective: Obtain a reliable 3D structure of the target protein.

- Procedure:

- Retrieve the protein sequence from a database like UniProt (e.g., ID: Q13509 for human βIII-tubulin).

- If an experimental structure is unavailable, perform homology modeling using software like Modeller. Use a high-identity template from the PDB (e.g., 1JFF for tubulin).

- Select the final model based on assessment scores (e.g., DOPE score) and stereo-chemical quality (e.g., Ramachandran plot via PROCHECK).

- Prepare the protein structure by adding missing hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and removing water molecules, except those critical for binding.

3.1.2. Ligand Library Preparation

- Objective: Prepare a database of compounds for screening.

- Procedure:

- Download a library of compounds (e.g., 89,399 natural compounds from the ZINC database or 4,561 from ChemDiv) in a format like SDF.

- Convert structures to PDBQT format using Open Babel.

- Minimize ligand geometries using a force field (e.g., MMFF94) to ensure structural stability.

3.1.3. High-Throughput Virtual Screening

- Objective: Rapidly screen the library against the target binding site.

- Procedure:

- Define the docking grid. Center the grid on the residue of the binding site of interest (e.g., the 'Taxol site') and set the dimensions to encompass the entire site (e.g., 20x16x16 Ã…).

- Use docking software such as AutoDock Vina for high-throughput screening.

- Set parameters:

exhaustiveness = 10, generatenum_poses = 10per ligand. - Perform docking and rank all compounds based on their calculated binding affinity (kcal/mol). Select the top 1,000 hits for further refinement.

3.1.4. Machine Learning-Based Refinement

- Objective: Filter virtual screening hits to identify truly "active" compounds.

- Procedure:

- Prepare Training Data: Use known active compounds (e.g., Taxol-site targeting drugs) and inactive compounds/decoys (generated using the DUD-E server).

- Generate Descriptors: Calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints (e.g., using PaDEL-Descriptor software) for both training data and the top 1,000 test hits.

- Train Classifiers: Employ supervised machine learning models (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machines) to distinguish active from inactive compounds.

- Predict & Select: Use the trained model to predict activity in the test hits, narrowing the list to a manageable number (e.g., 20) of high-confidence active compounds.

Protocol: Molecular Docking for Binding Mode Analysis

This protocol provides a detailed method for a more rigorous docking analysis of the shortlisted compounds [31] [30].

3.2.1. System Setup

- Use the same prepared protein and ligand files from the previous protocol.

- For the docking calculation, use a more exhaustive search parameter (e.g.,

exhaustiveness = 16or higher) to ensure comprehensive sampling of the binding pose.

3.2.2. Docking Execution and Analysis

- Execute molecular docking using software like AutoDock Vina, Schrödinger's Glide, or MOE.

- Generate multiple poses (e.g., 20-50) for each ligand.

- Analyze the top-ranked poses for consistent binding modes, specific hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and π-π stacking with key amino acid residues in the binding pocket.

Protocol: Molecular Dynamics Simulations

This protocol is used to assess the stability of the protein-ligand complexes identified from docking and to calculate binding free energies [29] [30].

3.3.1. System Preparation

- Objective: Create a solvated, neutralized system for simulation.

- Procedure:

- Use the top docking pose for the most promising ligands.

- Solvate the protein-ligand complex in a periodic box of water molecules (e.g., TIP3P model).

- Add ions (e.g., Naâº, Clâ») to neutralize the system's charge and mimic physiological salt concentration.

3.3.2. Simulation Parameters

- Use MD software such as GROMACS, AMBER, or NAMD.

- Apply a force field (e.g., CHARMM36, AMBERff14SB).

- Set the simulation time to at least 100 ns, though 300 ns provides more robust data for stability assessment.

- Maintain constant temperature (e.g., 310 K) and pressure (1 atm) using coupling algorithms (Berendsen or Parrinello-Rahman).

3.3.3. Trajectory Analysis

- Objective: Evaluate the stability and interaction quality of the complex.

- Key Metrics:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the structural stability of the protein and ligand over time. A stable or convergent RMSD suggests a stable complex.

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Assesses the flexibility of individual protein residues. Reduced flexibility in the binding site can indicate stable ligand binding.

- Radius of Gyration (Rg): Indicates the overall compactness of the protein.

- Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA): Measures the surface area of the protein accessible to solvent.

3.3.4. Binding Free Energy Calculations

- Use the Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) or MM/PBSA method on simulation snapshots.

- Calculate the binding free energy (ΔGbind) to quantitatively compare ligands. A more negative value indicates stronger binding. For example, a ΔGbind of -35.77 kcal/mol is significantly more favorable than -18.90 kcal/mol for a control [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogs key software and resources essential for executing the protocols described above.

Table 1: Key Software and Database Solutions for Structure-Based Drug Discovery

| Tool Name | Category/Type | Primary Function in Research | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) [32] | Integrated Software Suite | Structure-based design, molecular modeling, QSAR, and simulation. | Integrates cheminformatics, bioinformatics, and molecular modeling in a single platform; supports ADMET prediction. |

| Schrödinger Suite [32] | Integrated Software Platform | High-throughput virtual screening, free energy calculations, and lead optimization. | Integrates quantum mechanics, machine learning (e.g., DeepAutoQSAR), and advanced scoring functions (GlideScore). |

| AutoDock Vina [29] [30] | Molecular Docking Software | Performing virtual screening and predicting binding poses/affinities. | Fast, open-source; widely used for high-throughput screening with a good balance of speed and accuracy. |

| GROMACS/AMBER [29] [30] | Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulating the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. | High-performance engines for running nanosecond-scale MD simulations to assess complex stability. |

| PyMOL [29] | Molecular Visualization | Visualizing 3D structures of proteins, ligands, and their interactions. | Critical for analyzing and presenting docking and MD results (e.g., binding poses, interaction diagrams). |