Automating Synthesis Planning: A Guide to Data Extraction from Chemical Patents

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern techniques for extracting chemical reaction data from patent documents to power synthesis planning and computer-aided drug discovery.

Automating Synthesis Planning: A Guide to Data Extraction from Chemical Patents

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern techniques for extracting chemical reaction data from patent documents to power synthesis planning and computer-aided drug discovery. It explores the foundational importance of patents as primary sources of new chemical entities, details the latest automated extraction methodologies including LLMs and specialized NLP pipelines, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and offers a comparative analysis of available tools and databases. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current advancements to help efficiently leverage the vast knowledge embedded in chemical patents.

Why Chemical Patents are a Goldmine for Synthesis Data

Patents as the First Disclosure of New Chemical Entities

In the competitive landscape of chemical and pharmaceutical research, patents serve as the primary and often earliest public disclosure of novel chemical compounds [1]. On average, it takes an additional one to three years for a small fraction of these chemically novel compounds to appear in traditional scientific journals, meaning a vast majority are exclusively available through patent documents for a significant period [2] [1]. This positions patent literature as an indispensable resource for researchers engaged in synthesis planning and drug development, providing critical data on novel compounds, synthetic pathways, experimental conditions, and biological activities long before such information permeates the academic literature [3] [1]. The systematic extraction and semantic representation of this data is therefore foundational to modern, data-driven research and development.

The Critical Role of Patents in Chemical Disclosure

The Data Landscape

The volume of chemical information published annually is immense. The CAplus database holds over 32 million references to patents and journal articles, while the CAS REGISTRY contains more than 54 million chemical compounds and the CASREACT database over 39 million reactions [3]. Within this landscape, patents are the channel of first disclosure. It is estimated that around 10 million syntheses are published in the literature each year, with patents contributing a significant portion of this data [3].

Commercial databases like Elsevier’s Reaxys and CAS SciFinder provide high-quality, manually excerpted content but are costly and time-consuming to build and maintain [2] [1]. This creates a pressing need for automated approaches to data extraction to keep pace with the scale of publication and to make this information more accessible for synthesis planning research [3].

The Challenge of "Relevant" Compounds

A critical concept in processing chemical patents is the distinction between all mentioned compounds and those that are relevant to the patent's core invention. A "relevant" compound is one that plays a major role within the patent, such as a starting material, a key product, or a compound specified in the claim section [1].

Automated systems that extract every mentioned compound can quickly become overwhelmed with data, as relevant compounds typically constitute only a small fraction—around 10%—of all chemical entities mentioned in a patent document [1]. The ability to automatically identify these relevant compounds is therefore a fundamental step in creating useful, focused datasets for synthesis planning, as it mirrors the curation process of manual experts [1].

Methodologies for Data Extraction from Chemical Patents

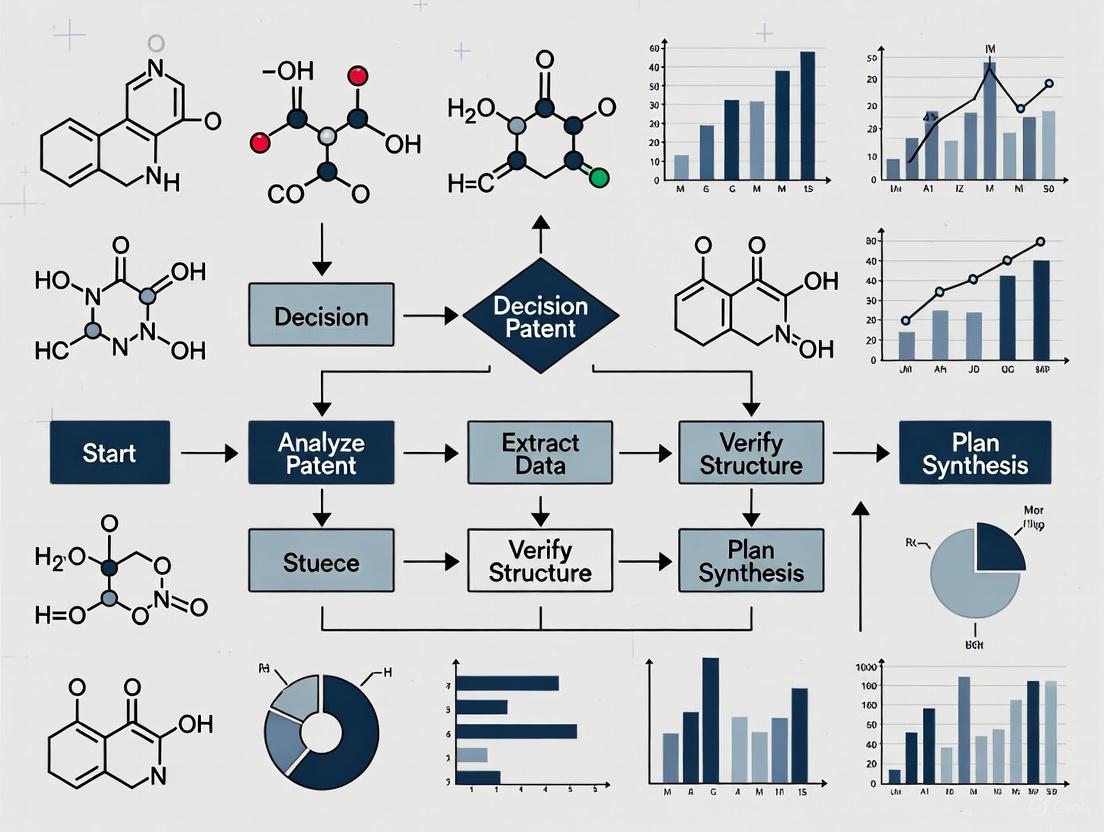

The automated extraction of chemical information from patents involves a multi-stage workflow, combining natural language processing, image analysis, and semantic reasoning.

Text and Data Mining Workflow

The general pipeline for extracting and classifying chemical data from patents involves normalization, entity recognition, structure assignment, and relevancy classification. The following diagram illustrates this integrated workflow.

Chemical Named Entity Recognition (NER)

Chemical NER is the first critical step, identifying text strings that refer to chemical compounds. State-of-the-art systems often use a hybrid of approaches:

- Grammar-Based Approaches: Tools like OPSIN (Open Parser for Systematic IUPAC Nomenclature) use the rules of IUPAC nomenclature to interpret systematic chemical names, overcoming the limitations of static dictionaries [3] [2].

- Statistical/Machine Learning Approaches: Supervised machine learning models are trained on manually annotated chemical terms to recognize chemical entities. These models can achieve high performance but require large, laboriously annotated corpora for training [1].

- Ensemble Systems: Combining multiple recognizers (e.g., CER and OCMiner) can improve overall performance by leveraging the strengths of different underlying methodologies [1].

Structure Assignment and Validation

Once a chemical entity is recognized from text, it must be associated with a machine-readable chemical structure. This is typically achieved through name-to-structure conversion tools like OPSIN [3] [2]. Validation is a crucial subsequent step. The PatentEye system, for instance, attempted to validate identified product molecules by comparing them to structure diagrams in the patent (using image interpretation packages like OSRA) and to any accompanying NMR spectra (using the OSCAR3 data recognition functionality) [3].

Relevance Classification

After extraction and structure assignment, a classifier determines the relevance of each compound. One study developed a system using a gold-standard set of 18,789 annotations, of which 10% were relevant, 88% were irrelevant, and 2% were equivocal [1]. The reported performance of the relevancy classifier was an F-score of 82% on the test set, demonstrating the feasibility of automating this complex task [1].

Extraction from Tables

Chemical patents frequently present key data—such as spectroscopic results, physical properties, and biological activity—in tables [2]. These tables are often larger and more complex than typical web tables. The ChemTables dataset was developed to advance the automatic categorization of tables based on semantic content (e.g., "Physical Data," "Preparation Information") [2]. State-of-the-art models like Table-BERT, which leverage pre-trained language models, have achieved a micro-averaged F~1~ score of 88.66% on this classification task, a critical step in targeting information extraction efforts [2].

Experimental Protocols for Extraction and Validation

The methodologies described in the literature can be formalized into reproducible experimental protocols for building and validating a chemical patent extraction pipeline.

Protocol: Building a Gold-Standard Annotation Corpus

This protocol is fundamental for training and evaluating statistical NER and relevance classification models [1].

Table: Key Data Elements for Protocol 1

| Data Element | Description & Example |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Create a manually annotated set of patent documents for model training and testing. |

| Input Materials | Full-text patent documents from major offices (e.g., EPO, USPTO, WIPO). |

| Annotation Guidelines | A detailed document defining what constitutes a chemical entity and the criteria for "relevance" [1]. |

| Workflow | 1. Select a representative sample of patents.2. Train multiple domain-expert annotators.3. Annotate documents independently.4. Harmonize annotations to resolve discrepancies. |

| Quality Control | Measure inter-annotator agreement (e.g., Cohen's Kappa) to ensure consistency. |

Protocol: Integrated Reaction Extraction with Validation

This protocol is based on the PatentEye system, which focused on extracting complete reaction information with validation checks [3].

Table: Key Data Elements for Protocol 2

| Data Element | Description & Example |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Extract synthetic reactions from patents and validate the identity of the product. |

| Input Materials | Patent documents in a text-based format (XML, HTML) to avoid OCR errors [3]. |

| Software Tools | OSCAR (NER), ChemicalTagger (syntactic analysis), OPSIN (name-to-structure), OSRA (image-to-structure) [3]. |

| Workflow | 1. Identify passages describing synthesis.2. Extract reactants, products, and quantities.3. Convert chemical names to structures.4. Validate product structure against diagrams (OSRA) and/or reported NMR spectra (OSCAR3). |

| Performance Metrics | Precision and Recall for reactants/products; Accuracy for product identification (PatentEye reported 92% product ID accuracy) [3]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key software tools and resources that form the essential toolkit for extracting chemical data from patents.

Table: Essential Tools for Chemical Patent Data Extraction

| Tool/Resource Name | Function & Role in the Extraction Workflow |

|---|---|

| OPSIN | An open-source tool for converting systematic IUPAC chemical names into machine-readable chemical structures, crucial for structure assignment [3] [2]. |

| OSCAR (Open Source Chemistry Analysis Routines) | A named entity recognition tool specifically designed to identify chemical names and terms in scientific text [3]. |

| ChemicalTagger | A tool for syntactic analysis of chemical text, using grammar-based approaches to parse sentences and identify the roles of chemical entities (e.g., solvent, reactant) [3]. |

| OSRA (Optical Structure Recognition Application) | An image-to-structure converter used to interpret chemical structure diagrams in patent documents, enabling validation of text-derived structures [3]. |

| Reaxys Name Service | A commercial service used to generate, validate, and standardize chemical structures from names, often used in ensemble systems to ensure data quality [1]. |

| Table-BERT | A state-of-the-art neural network model based on pre-trained language models, used for the semantic classification of tables in chemical patents [2]. |

Quantitative Performance of Extraction Systems

The performance of automated systems is continuously improving, as evidenced by published benchmarks across different tasks.

Table: Performance Metrics of Automated Extraction Systems

| Extraction Task | Reported Performance Metric | Key Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Extraction (PatentEye) | Precision: 78%, Recall: 64% [3] | Performance for determining reactant identity and amount. |

| Reaction Extraction (PatentEye) | Product Identification Accuracy: 92% [3] | Validation against diagrams and spectra improves accuracy. |

| Chemical Compound Recognition | F-score: 86% (Test Set) [1] | Performance of an ensemble system (CER & OCMiner) on entity recognition. |

| Relevance Classification | F-score: 82% (Test Set) [1] | Performance of a classifier in identifying "relevant" compounds. |

| Patent Table Classification (Table-BERT) | Micro F~1~: 88.66% [2] | Classification of tables by semantic type (e.g., physicochemical data, preparation). |

Patent documents are unequivocally the earliest and most comprehensive source for disclosing new chemical entities and their synthetic pathways. The ability to automatically extract, semantify, and classify this information is no longer a theoretical pursuit but a practical necessity. Methodologies combining robust named entity recognition, name-to-structure conversion, and machine learning-based relevance filtering have demonstrated performance levels that make them viable for augmenting and scaling traditional manual curation. For researchers in synthesis planning, leveraging these automated approaches and the tools that implement them is key to unlocking the vast, untapped knowledge contained within global patent literature, thereby accelerating the journey from novel compound conception to successful synthesis.

The Manual Curation Bottleneck and the Need for Automation

The application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in drug discovery represents a paradigm shift, offering the potential to drastically reduce the time and cost associated with bringing new therapeutics to market. However, this AI revolution is being stifled by a fundamental data bottleneck. The performance of any AI model is intrinsically limited by the quality, quantity, and relevance of the data on which it is trained [4]. Manual curation, the traditional method for building the chemical knowledge bases that power synthesis planning, has become a critical constraint. It is a slow, expensive, and inherently limited process, creating a bottleneck that prevents AI systems from realizing their full, transformative potential [5] [4].

This bottleneck is particularly acute in the context of chemical patents. Patents are often the first and sometimes the only disclosure of novel compounds and reactions; it can take one to three years for this information to appear in scientific journals, if it appears at all [2]. Consequently, patents are indispensable resources for understanding the state of the art and planning new synthetic routes. Yet, the valuable data within these documents—including detailed experimental procedures, physicochemical properties, and pharmacological results—is frequently locked away in formats that are difficult for machines to process, such as complex tables, images of chemical structures, and unstructured text [2]. The reliance on manual extraction is no longer tenable given the sheer volume of patent literature published annually [5] [2].

Framed within a broader thesis on data extraction for synthesis planning research, this whitepaper argues that overcoming the manual curation bottleneck through automation is not merely an efficiency gain but a strategic imperative. This document will provide an in-depth technical analysis of the bottleneck's causes, detail automated methodologies and datasets that are enabling progress, and quantify the performance of state-of-the-art models that are paving the way for a fully automated, data-driven future in chemical research and development.

The process of manually extracting chemical information from patents for commercial databases is conducted by expert curators, but this approach faces significant and scalable challenges.

- Volume and Velocity: The global patent landscape is vast and growing, with over 200,000 chemical substance patents filed annually across major jurisdictions [5]. Manually processing this deluge of information is economically and logistically infeasible, leading to significant data acquisition delays [2].

- Data Incompleteness and Bias: Manual curation from public sources like academic literature is plagued by publication bias. Public databases are overwhelmingly populated with positive results—successful reactions and active compounds—while the crucial information about failed experiments and negative results is rarely published [4]. This creates a skewed reality for AI models, leading to over-optimistic predictions and a failure to learn from past mistakes [4] [6].

- Lack of Commercial Context: Data sourced from academic literature is devoid of the commercial context vital for industrial R&D. It provides little information on a compound's manufacturing feasibility, formulation challenges, stability, or cost of goods, meaning an AI model might design a molecule that is potent but commercially non-viable [4].

Table 1: Quantitative Challenges in Chemical Patent Data Extraction

| Challenge Dimension | Quantitative Metric | Impact on Manual Curation and AI Training |

|---|---|---|

| Document Volume | Over 200,000 chemical patents filed annually [5] | Impossible for human teams to process comprehensively, leading to data gaps. |

| Table Size | Average of 38.77 rows per table in chemical patents [2] | Increases complexity and time required for extraction significantly compared to web tables (avg. 12.41 rows). |

| Data Diversity | Various table types: spectroscopic data, preparation procedures, pharmacological results [2] | Requires curator expertise in multiple domains, slowing down the process. |

| Publication Lag | 1-3 years for compounds to appear in journals after patent filing [2] | Manual systems reliant on journals provide retrospective, not current, intelligence. |

Technical Foundations: Datasets and Models for Automated Extraction

To overcome the limitations of manual curation, the research community has developed specialized datasets and models to automate the interpretation of chemical patents. These resources are fundamental to training and evaluating the machine learning systems that power modern chemical text-mining pipelines.

The ChemTables Dataset for Semantic Classification

A primary technical challenge is that key chemical data in patents is often presented in tables, which exhibit substantial heterogeneity in both content and structure [2]. To enable research on automatic table categorization, the ChemTables dataset was developed.

Dataset Description: ChemTables is a publicly available dataset consisting of 788 chemical patent tables annotated with labels indicating their semantic content type [7] [2]. The dataset provides a standardized 60:20:20 split for training, development, and test sets, facilitating direct comparison between different machine learning methods [7].

Experimental Protocol for Baseline Models: Researchers established strong baselines for the table classification task by applying and comparing several state-of-the-art neural network models [2].

- Input Representation: Table content is processed into a format suitable for model input.

- Model Architectures:

- TabNet: Uses an LSTM to encode tokens in each cell, treats the encoded table as an image, and uses a Residual Network for classification [2].

- ResNet: A convolutional neural network applied directly to the table representation [2].

- Table-BERT: Leverages the power of pre-trained language models (like BERT) adapted for table understanding [2].

- Training: Models are trained on the ChemTables training set to predict the semantic label of a given table.

- Evaluation: Performance is measured using the micro-averaged ( F_1 ) score on the held-out test set.

Results: The best performing model, Table-BERT, achieved a micro-averaged ( F_1 ) score of 88.66%, demonstrating the efficacy of pre-trained language models for this complex task [2]. This level of accuracy is a critical first step in an automated pipeline, as it allows for the routing of different table types to specialized extraction tools.

The Smiles2Actions Model for Inferring Experimental Procedures

Perhaps the most ambitious technical advancement is the direct prediction of executable experimental procedures from a text-based representation of a chemical reaction.

Model Objective: The goal of Smiles2Actions is to convert a chemical equation (represented in the SMILES format) into a complete sequence of synthesis actions (e.g., add, stir, heat, extract) necessary to execute the reaction in a laboratory [8].

Experimental Protocol: The model was developed and evaluated through a rigorous process [8].

- Data Set Generation:

- Source: The Pistachio database, containing millions of reactions from patents.

- Processing: 3,464,664 reactions with experimental procedure text were processed using a natural language model (Paragraph2Actions) to extract action sequences.

- Post-processing: Records were filtered and standardized, resulting in a final high-quality dataset of 693,517 chemical equations and associated action sequences.

- Model Training: Three different data-driven models were trained on this dataset:

- A nearest-neighbor model based on reaction fingerprints.

- Two deep-learning sequence-to-sequence models based on the Transformer and BART architectures.

- Evaluation: Performance was assessed using the normalized Levenshtein similarity between predicted and original procedures. Furthermore, a trained chemist conducted a blind analysis of 500 predicted action sequences to assess their executability.

Results: The sequence-to-sequence models demonstrated a high level of competence. The best model achieved a normalized Levenshtein similarity of 50% for 68.7% of reactions [8]. Most importantly, the expert chemist assessment revealed that over 50% of the predicted action sequences were adequate for execution without any human intervention [8]. This represents a monumental leap towards fully automating synthesis planning from patent data.

Visualization of Automated Workflows

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the logical relationships and workflows of the key automated systems described in this paper.

Diagram 1: Semantic Table Classification with ChemTables

Diagram 2: Procedure Prediction with Smiles2Actions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Software Solutions

Automating data extraction from chemical patents requires a suite of specialized software tools and datasets. The table below details key "research reagents" in this context—the essential resources that enable scientists to build and deploy automated systems.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Automated Chemical Data Extraction

| Tool / Dataset Name | Type | Primary Function in Automation |

|---|---|---|

| ChemTables Dataset [7] [2] | Annotated Dataset | Provides gold-standard data for training and evaluating machine learning models to classify tables in chemical patents by content type (e.g., spectroscopic, pharmacological). |

| Paragraph2Actions Model [8] | Natural Language Processing Model | Converts free-text experimental procedures from patents into a structured, machine-readable sequence of synthesis actions. Serves as a key component in automated procedure extraction. |

| Pistachio Database [8] | Chemical Reaction Database | A commercial source of millions of patent-derived reactions with associated SMILES strings and procedure text. Used as a large-scale data source for training predictive models like Smiles2Actions. |

| Table-BERT [2] | Machine Learning Model | A pre-trained language model adapted for table understanding. Provides state-of-the-art performance (88.66% F1 score) on the semantic classification of chemical patent tables. |

| OPSIN [2] | Name-to-Structure Tool | A rule-based system that converts systematic chemical names found in patent text into machine-readable structural representations (e.g., SMILES, InChI). Critical for identifying novel compounds. |

The evidence is clear: the manual curation of chemical data from patents is a bottleneck that actively impedes progress in AI-driven synthesis planning and drug discovery. However, as demonstrated by technical breakthroughs like the ChemTables dataset and the Smiles2Actions model, automation presents a viable and powerful solution. These tools are already achieving high levels of accuracy in classifying complex patent data and predicting executable laboratory procedures.

The future path involves the continued development and integration of these specialized AI models into seamless, end-to-end workflows. The vision is a system where a chemical ChatBot can interact with a medicinal chemist, ingesting a target molecule and instantly providing not only a viable synthetic route but also a fully detailed, executable experimental procedure derived from the collective intelligence embedded in global patent literature [6]. Achieving this vision will require a concerted effort across the industry to treat chemical data stewardship as a central pillar of R&D and to fully embrace the automated tools that are unlocking the next frontier of innovation.

Chemical patents are a primary channel for disclosing novel compounds and reactions, often preceding their appearance in scientific journals by one to three years [2]. The extraction of structured data on chemical structures, reactions, and experimental conditions from these patents is therefore crucial for accelerating synthesis planning and drug development research. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of methodologies for identifying and extracting these core information types, framed within the context of building automated systems for chemical synthesis planning.

Key chemical data in patents is frequently presented in tables, which can vary greatly in both content and structure [2]. The heterogeneity in how this information is presented creates significant challenges for automated extraction, necessitating sophisticated text-mining approaches. This guide details the current state-of-the-art methods for tackling these challenges, with a focus on practical implementation for research applications.

Chemical Structures in Patents

Representation Formats and Extraction Methods

Chemical structures in patents are disclosed through multiple representation formats, each requiring distinct processing approaches. Markush structures, which describe a generic chemical structure with variable parts, are commonly used in patent claims but present particular challenges for computational representation [9]. These structures are often presented as images, requiring conversion to machine-readable formats.

Table 1: Chemical Structure Representation Formats in Patents

| Format Type | Description | Extraction Methods | Primary Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic Names | IUPAC or other systematic nomenclature | OPSIN [2], MarvinSketch [2] | Compound description in text |

| Markush Structures | Generic structures with variable substituents | Specialized Markush search tools [9] | Patent claims for broad protection |

| SMILES | Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System | Direct extraction or conversion from other formats [8] | Computational processing, database storage |

| Structural Images | Chemical structures as figures | Optical chemical structure recognition | Patent figures and drawings |

Systematic chemical names found in the text can be converted to structural representations using tools such as OPSIN and MarvinSketch [2]. For structures embedded as images, optical chemical structure recognition techniques are required to generate connection tables or linear notations. The resulting structural data forms the foundation for subsequent analysis of reactions and conditions.

Experimental Methodology for Structure Extraction

The extraction of chemical structures from patent documents follows a multi-step workflow. First, document segmentation identifies sections containing chemical information, particularly focusing on the claims and experimental sections. For textual representations, named entity recognition models specifically trained on chemical nomenclature identify systematic names, which are then converted to structural formats using rule-based tools.

For image-based structures, the workflow involves:

- Image Detection: Locating chemical structure diagrams within patent documents

- Optical Recognition: Converting graphical elements to structural representations

- Validation: Cross-referencing with textual descriptions to ensure accuracy

Specialized databases like SciFinder-n provide Markush search capabilities, enabling researchers to find patents containing specific structural patterns [9].

Chemical Reactions and Experimental Procedures

Reaction Representation and Prediction

Chemical reactions in patents represent transformations from precursors to products, with associated reagents and conditions. These reactions can be represented in text-based formats such as SMILES, which facilitates computational processing [8]. Recent advances in artificial intelligence have enabled the prediction of synthetic routes through retrosynthetic models, but converting these routes to executable experimental procedures remains challenging [8].

Table 2: Reaction Data Types in Chemical Patents

| Data Category | Specific Elements | Extraction Challenges | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Participants | Reactants, reagents, catalysts, solvents, products | Distinguishing reactants from reagents [8] | Reaction prediction, similarity analysis |

| Transformation Information | Reaction centers, bond changes, reaction classes | Automatic reaction mapping | Retrosynthetic analysis |

| Experimental Actions | Addition, stirring, heating, filtration, extraction [8] | Interpreting procedural text | Automated synthesis, procedure transfer |

| Quantity Information | Amounts, concentrations, stoichiometry | Unit normalization, handling implicit information | Reaction scaling, yield optimization |

The prediction of complete experimental procedures from reaction equations represents a significant advancement in automating chemical synthesis. As demonstrated by Vaucher et al., natural language processing models can extract action sequences from patent text, enabling the creation of datasets for training procedure prediction models [8].

Workflow for Procedure Extraction and Prediction

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for extracting chemical procedures from patents and predicting them for novel reactions:

Figure 1: Workflow for extracting and predicting chemical procedures

As shown in Figure 1, the process begins with a patent database such as Pistachio, which contains records of reactions published in patents [8]. Experimental procedure text is processed using natural language models like Paragraph2Actions to extract action sequences [8]. These sequences undergo standardization, including tokenization of numerical values and compound references, to create a training dataset. This dataset then trains sequence-to-sequence models, such as Transformer or BART architectures, which can predict procedure steps for new reactions given their SMILES representations [8].

Experimental Conditions and Numerical Data

Types of Experimental Conditions

Experimental conditions encompass the parameters under which chemical reactions are performed, including temperature, pressure, time, atmosphere, and purification methods. In patents, this information appears both in procedural text and in structured tables, requiring different extraction approaches.

Physical and spectroscopic data characterizing compounds are frequently presented in tables, which show substantial variation in structure and content [2]. These tables can include melting points, spectral data (NMR, IR, MS), solubility information, and physical properties essential for compound identification and characterization.

Table 3: Experimental Condition Categories in Chemical Patents

| Condition Type | Specific Parameters | Extraction Methods | Impact on Reactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature Conditions | Reaction temperature, heating/cooling rates, temperature ranges | Numerical extraction with unit normalization | Reaction rate, selectivity, side products |

| Time Parameters | Reaction duration, addition times, workup times | Tokenization of ranges (e.g., "overnight") [8] | Conversion, decomposition |

| Atmosphere/Solvent | Inert atmosphere, solvent system, concentration | Named entity recognition, solvent classification | Solubility, reactivity, mechanism |

| Workup/Purification | Extraction, filtration, chromatography, crystallization | Action type classification [8] | Product purity, yield |

The extraction of conditions from text involves identifying relevant numerical values and their associated units, while table extraction requires understanding the table structure and semantics. Categorizing tables based on content type is a fundamental step in this process [2].

Table Processing Methodology

Tables in chemical patents present unique challenges due to their structural complexity, frequent use of merged cells, and larger average size compared to web tables [2]. The methodology for processing these tables involves:

- Table Classification: Semantically categorizing tables based on content using models like Table-BERT, which has demonstrated performance of 88.66 micro-averaged F₁ score on chemical patent tables [2]

- Structure Recognition: Identifying table components (headers, data cells, footnotes) and their relationships

- Content Extraction: Parsing numerical data, units, and associated compound identifiers

- Data Normalization: Standardizing units and numerical representations for computational use

The ChemTables dataset, consisting of 7,886 chemical patent tables with content type labels, enables the development and evaluation of table classification methods [10]. This dataset reflects the real-world distribution of table types in chemical patents, with an average of 38.77 rows per table—significantly larger than typical web tables [2].

Computational Tools and Research Reagents

Successful extraction of chemical information from patents requires both computational tools and chemical knowledge. The following table details key resources in the "scientist's toolkit" for this research domain.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Patent Data Extraction

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChemTables Dataset | Dataset | Provides labeled patent tables for training classification models [10] | Method development and evaluation |

| Paragraph2Actions | NLP Model | Extracts action sequences from experimental procedure text [8] | Procedure understanding and prediction |

| OPSIN | Tool | Converts systematic chemical names to structures [2] | Structure extraction from text |

| Table-BERT | Model | Classifies tables in chemical patents based on content [2] | Semantic table categorization |

| SciFinder-n | Database | Provides Markush structure search capabilities [9] | Advanced patent structure searching |

| Smiles2Actions | Model | Converts chemical equations to experimental actions [8] | Automated procedure prediction |

Integrated System Architecture

The relationship between key components in a comprehensive patent data extraction system can be visualized as follows:

Figure 2: System architecture for patent data extraction

As illustrated in Figure 2, a comprehensive system requires integrated modules for processing different information types within patents. The text processing module handles experimental procedures and descriptive text, the table processing module extracts structured numerical data, and the structure parser converts chemical representations to machine-readable formats. The output is a unified structured dataset containing compounds, reactions, and associated conditions.

The extraction of key chemical information from patents—structures, reactions, and conditions—provides critical data for synthesis planning research. Methods such as table classification with Table-BERT and procedure prediction with sequence-to-sequence models have demonstrated promising results, but challenges remain in handling the diversity and complexity of patent information.

Future research directions include developing more integrated approaches that jointly extract and link structures, reactions, and conditions; improving generalization across patent writing styles; and enhancing the robustness of extraction methods to layout variations. As these methods mature, they will increasingly support drug development professionals in efficiently leveraging the wealth of synthetic knowledge contained in the patent literature.

The Critical Timeliness of Patent Data in Drug Discovery

In the competitive landscape of drug discovery, pharmaceutical patents represent both the foundational intellectual property protecting innovative therapies and a rich, rapidly evolving source of technical information for synthesis planning research. The temporal aspect of patent data operates in two critical dimensions: the strategic timing of patent filings to maximize commercial exclusivity periods, and the accelerating pace at which patent-derived chemical information must be extracted and utilized to maintain competitive research advantages. This guide examines the intersection of these dimensions, providing researchers with methodologies to leverage temporally-sensitive patent data for synthesis planning while navigating the complex intellectual property framework governing pharmaceutical innovation.

The strategic importance of patent timing stems from substantial structural challenges in drug development. The nominal 20-year patent term begins from the earliest filing date, typically during initial discovery phases, yet the mandatory research, development, and regulatory review processes consume 5-10 years of this term before commercial sales commence [11]. This erosion significantly shortens effective market exclusivity, creating intense pressure to optimize both patent strategy and research utilization of published patent information.

The Pharmaceutical Patent Timeline: Structural Erosion and Compensation Mechanisms

Foundational IP Framework and Term Erosion

The United States patent system establishes a nominal 20-year term from the earliest effective filing date under 35 U.S.C. § 154(a)(2) [11]. For pharmaceutical innovations, this creates a structural disadvantage because the patent clock begins during early discovery or clinical trial phases, often years before a therapeutic candidate reaches the market. The average research and development lifecycle routinely consumes years of the patent term before marketing approval is even sought, with patent pendency (the period between patent filing and grant) averaging 3.8 years for new chemical entities [11].

This structural erosion has significant implications for both patent holders and researchers analyzing patent data. The diminishing effective patent life creates commercial pressure to accelerate development timelines, which in turn affects the timing and content of patent publications that synthesis researchers rely upon for the latest chemical advances.

Legislative Compensation Mechanisms

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 (Hatch-Waxman Act) provides corrective instruments to counteract patent term erosion [11]. This legislation established a balanced approach between innovation incentives and generic competition through three key mechanisms:

- Patent Term Extension (PTE): Restores patent life lost during FDA regulatory review, with a maximum duration of 5 years and a cap ensuring the total remaining patent term from approval date does not exceed 14 years [11].

- Patent Term Adjustment (PTA): Compensates for USPTO administrative delays during patent prosecution, adding time directly to the nominal 20-year term with no statutory maximum [11].

- Regulatory Exclusivities: Provides additional non-patent protection periods (e.g., 5-year New Chemical Entity exclusivity) that run concurrently with patent protection [11].

Table 1: Pharmaceutical Patent Term Compensation Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Legal Basis | Purpose | Maximum Duration | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patent Term Extension (PTE) | 35 U.S.C. § 156 | Compensate for FDA review delays | 5 years | Cannot exceed 14 years effective patent life from approval |

| Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) | 35 U.S.C. § 154 | Compensate for USPTO delays | No statutory maximum | Calculated based on specific USPTO delays |

| Regulatory Exclusivity | Hatch-Waxman Act | Protect regulatory data | 3-5 years depending on product type | Runs concurrently with patent protection |

For researchers tracking pharmaceutical patents, understanding these mechanisms is essential for accurately predicting when key compounds will become available for further research and generic development, thus informing synthesis planning timelines.

Strategic Patent Timing for Maximum Impact

The Patent Filing Dilemma in Drug Discovery

Startups and established pharmaceutical companies face critical timing decisions regarding patent filings. Filing too early can result in weak or speculative claims lacking sufficient experimental data to withstand scrutiny, while filing too late risks loss of rights due to public disclosures or competitor preemption [12]. Early patent filings may also expire before product commercialization, significantly eroding effective patent life and reducing the window of market exclusivity [12].

The financial implications of patent timing are substantial. The pharmaceutical industry faces a projected $236 billion patent cliff between 2025 and 2030, involving approximately 70 high-revenue products [11]. When patents lapse, small-molecule drugs typically lose up to 90% of revenue within months, with average price declines of 25% for oral medications and 38-48% for physician-administered drugs [11].

Strategic Timing Solutions

Five key strategies can optimize patent filing timing and maximize the research utility of patent data:

Coordinate patent filings with public disclosures: Public disclosure before filing destroys novelty in most jurisdictions. Applications should be filed before conferences, publications, or investor presentations (without NDAs) [12].

Align patent filing with development milestones: File when sufficient data supports the invention, using follow-up applications to capture new data or applications [12].

Utilize divisional applications: Pursue protection for different aspects disclosed but not claimed in parent applications, such as methods of use, formulations, or combination therapies [12].

Monitor competitor activity: In competitive fields, regular patent landscape reviews help identify emerging threats and opportunities, potentially necessitating earlier filing [12].

Balance patent lifetime with regulatory timelines: Consider supplementary protection certificates or patent term extensions, timing filings to maximize exclusivity at product launch [12].

Table 2: Strategic Patent Timing Approaches

| Strategy | Implementation | Research Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Disclosure Coordination | File before public presentations | Ensures novel technical information enters public domain predictably |

| Milestone Alignment | Base filing on sufficient experimental data | Provides more complete synthesis information in published patents |

| Divisional Applications | Protect different aspects of invention | Enables broader mining of formulation and method patents |

| Competitor Monitoring | Regular landscape reviews | Identifies emerging synthetic routes and compound classes |

| Regulatory Balance | Coordinate with development timeline | Predicts availability of compounds for further research |

Advanced Methodologies for Temporal Patent Data Extraction

Automated Chemical Reaction Extraction from Patents

The extraction of chemical synthesis information from patents presents significant challenges due to the prose format of experimental procedures in patent documents. Traditional conversion of unstructured chemical recipes to structured, automation-friendly formats requires extensive human intervention [13]. Recent advances in artificial intelligence, particularly large language models (LLMs), have dramatically accelerated this process while improving data quality.

A comprehensive pipeline for chemical reaction extraction from USPTO patents demonstrates the potential for high-throughput temporal data mining [14]. This approach showed that automated extraction could enhance existing datasets by adding 26% new reactions from the same patent set while identifying errors in previously curated data [14].

Figure 1: Automated Chemical Reaction Extraction Pipeline

Experimental Protocol: LLM-Assisted Reaction Mining

Objective: Extract high-quality chemical reaction data from USPTO patent documents using large language models to enhance synthesis planning databases.

Materials and Data Sources:

- Patent Corpus: US patents from USPTO with International Patent Classification (IPC) code 'C07' (Organic Chemistry) [14]

- Validation Dataset: Open Reaction Database (ORD) containing previously extracted reactions from February 2014 for performance benchmarking [14]

- Computational Resources: Access to LLM APIs (GPT-3.5, Gemini 1.0 Pro, Llama2-13b, or Claude 2.1) for entity recognition [14]

Methodology:

Patent Collection and Preprocessing:

- Retrieve patents from Google Patents service filtered by IPC code 'C07'

- Extract and clean text content from patent documents, preserving chemical nomenclature and experimental sections

Reaction Paragraph Identification:

- Implement a Naïve-Bayes classifier trained on manually labeled corpus of reaction paragraphs

- Utilize classifier with documented performance (precision = 96.4%, recall = 96.6%) to identify reaction-containing paragraphs [14]

- Filter non-relevant text to reduce computational load on subsequent LLM processing

Chemical Entity Recognition Using LLMs:

- Apply zero-shot Named Entity Recognition (NER) capability of pretrained LLMs

- Extract chemical reaction entities including: reactants, solvents, workup procedures, reaction conditions, catalysts, and products with associated quantities [14]

- Process identified reaction paragraphs through multiple LLMs for comparative performance assessment

Data Standardization and Validation:

- Convert identified chemical entities from IUPAC names to SMILES format for standardization

- Perform atom mapping between reactants and products to validate reaction correctness

- Flag reactions with mapping inconsistencies for manual review or exclusion

Performance Metrics:

- Comparison against existing USPTO dataset using same patent corpus

- Quantitative assessment of new reactions identified

- Error analysis of previously curated data

- Processing throughput (patents processed per unit time)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for Patent Data Extraction

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Patent Data Extraction

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| USPTO Patent Database | Primary source of patent documents | Provides raw text data for chemical information extraction |

| IBM RXN for Chemistry Platform | Deep learning model for action sequence extraction | Converts experimental procedures to structured synthesis actions [13] |

| Open Reaction Database (ORD) | Structured reaction database schema | Validation benchmark for extracted reactions [14] |

| ChemicalTagger | Grammar-based chemical entity recognition | Rule-based extraction of chemical entities from text [14] |

| Naïve-Bayes Classifier | Text classification for reaction paragraphs | Filters patent text to identify reaction-containing sections [14] |

| LLM APIs (GPT, Gemini, Claude) | Named Entity Recognition for chemical data | Extracts structured reaction information from patent prose [14] |

| CheMUST Dataset | Annotated chemical patent tables | Training data for table extraction algorithms [7] |

Temporal Analysis Framework for Patent Landscapes

The accelerating pace of pharmaceutical research necessitates increasingly sophisticated temporal analysis of patent data. Researchers must track not only when patents are published but also how quickly chemical information from these patents can be integrated into synthesis planning systems.

Figure 2: Temporal Pathway from Patent Filing to Research Utilization

The critical path from patent filing to research utilization demonstrates the compounding value of reducing extraction timelines. Each reduction in processing time accelerates the entire drug discovery pipeline, potentially shaving months or years from development timelines for new therapies.

The critical timeliness of patent data in drug discovery represents a multifaceted challenge requiring integrated expertise across intellectual property law, data science, and synthetic chemistry. Researchers who successfully navigate this complex landscape stand to gain significant advantages in synthesizing novel compounds and developing innovative therapeutic strategies. As artificial intelligence tools continue to evolve, the extraction and utilization of patent information will further accelerate, potentially reshaping competitive dynamics in pharmaceutical research. The organizations that thrive in this environment will be those that develop seamless workflows integrating strategic patent analysis with state-of-the-art data extraction capabilities, transforming patent publications from mere legal documents into valuable research assets.

Modern Techniques for Automated Patent Extraction

Leveraging Large Language Models (LLMs) for Entity and Relation Extraction

The rapid advancement of Large Language Models (LLMs) has revolutionized information extraction from complex scientific documents, particularly in the domain of chemical patent analysis for synthesis planning research. Chemical patents represent a rich repository of structured knowledge containing detailed descriptions of novel molecules, synthetic methodologies, reaction conditions, and functional applications. However, extracting this information manually is time-consuming, labor-intensive, and prone to inconsistencies, creating a significant bottleneck in research and development workflows.

LLMs offer a transformative solution to these challenges through their advanced natural language understanding capabilities and contextual reasoning. When properly leveraged, these models can automatically identify chemical entities (reactants, products, catalysts, solvents) and their complex relationships (reaction pathways, conditions, yields) from unstructured patent text, enabling the construction of structured knowledge bases for synthesis planning [14]. This technical guide examines the methodologies, architectures, and experimental protocols for implementing LLM-powered entity and relation extraction systems specifically tailored for chemical patent analysis, with emphasis on practical implementation considerations for researchers and drug development professionals.

The integration of LLMs into chemical data extraction pipelines addresses several critical challenges in the field: the exponential growth of chemical literature [15], the heterogeneity of data representations across patent documents [14], and the need for high-quality structured data to train predictive models for retrosynthesis and reaction optimization [16]. By systematically implementing the approaches described in this guide, research institutions and pharmaceutical companies can significantly accelerate their discovery pipelines and enhance the efficiency of synthesis planning research.

Technical Foundations

LLM Architectures for Chemical Information Extraction

The application of LLMs to chemical entity and relationship extraction builds upon several foundational architectures adapted to domain-specific requirements. The Transformer architecture, with its self-attention mechanism, forms the bedrock of modern LLMs, enabling parallel processing of token sequences and capturing long-range dependencies in chemical patents [17]. Several specialized architectures have demonstrated particular efficacy for chemical data extraction:

Encoder-only models like BERT and its variants (BioBERT, SciBERT) excel at understanding contextual relationships within patent text through bidirectional processing. These models are particularly effective for named entity recognition (NER) tasks where comprehensive context is essential for accurate identification of chemical entities [14]. The pretraining-finetuning paradigm allows these models to be adapted to chemical patent processing with relatively small amounts of labeled data.

Decoder-only models from the GPT family leverage autoregressive generation capabilities to produce structured outputs from unstructured patent text. These models can generate extraction results in standardized formats (JSON, XML) while maintaining contextual awareness across long patent documents [18]. Their generative nature makes them particularly suitable for relationship extraction tasks where the output structure may be complex.

Encoder-decoder models provide a balanced approach, with the encoder processing patent text and the decoder generating structured extractions. This architecture is especially valuable for complex extraction tasks requiring both comprehensive understanding of input text and generation of sophisticated output structures [17].

Table 1: LLM Architectures for Chemical Patent Extraction

| Architecture Type | Representative Models | Strengths | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-only | BERT, BioBERT, SciBERT | Bidirectional context understanding, high accuracy on NER | Chemical named entity recognition, sequence labeling |

| Decoder-only | GPT-series, LLaMA, Falcon | Flexible output generation, few-shot learning | Relationship extraction, structured data generation |

| Encoder-decoder | T5, BART | Balanced understanding and generation | Complex information extraction, data transformation |

Chemical Representation Learning

Effective entity and relationship extraction from chemical patents requires specialized representation approaches that capture both linguistic and chemical semantics. Multiple representation schemes have been developed to encode chemical information in formats compatible with LLM processing:

SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) provides a string-based representation of molecular structure that can be processed by text-based LLMs. While SMILES strings enable the application of standard NLP techniques to chemical structures, they can be ambiguous and sensitive to minor syntactic variations [16]. Recent approaches have addressed these limitations through canonicalization and augmentation techniques.

Molecular graph representations capture the fundamental structure of chemicals as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) can process these representations to generate embeddings that capture structural similarities and functional properties [15]. Hybrid approaches that combine LLMs with GNNs have shown promise in integrating textual and structural information.

IUPAC nomenclature provides systematic naming conventions that are frequently used in patent documents. While these names contain rich structural information, their complexity presents challenges for automated processing. LLMs fine-tuned on chemical nomenclature can learn to parse these names and extract structural information [14].

The representation approach significantly impacts extraction performance. A comparative analysis of extraction pipelines found that systems incorporating multiple representation schemes achieved 18% higher F1 scores on complex relationship extraction tasks compared to single-representation approaches [18].

Methodology

Entity Extraction Protocols

The extraction of chemical entities from patent documents involves a multi-stage process that combines LLM capabilities with domain-specific validation. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive approach optimized for chemical patents:

Step 1: Patent Preprocessing and Segmentation

- Convert patent documents from PDF/HTML to clean text while preserving structural elements (headings, paragraphs, claims)

- Identify and extract relevant sections (abstract, description, examples, claims) using rule-based classifiers or fine-tuned LLMs

- Segment text into coherent passages using a Naïve-Bayes classifier trained on manually annotated patent corpora, achieving precision of 96.4% and recall of 96.6% in identifying reaction-containing paragraphs [14]

Step 2: Named Entity Recognition with LLMs

- Implement a hybrid NER approach combining prompt-based extraction with fine-tuned models

- For prompt-based extraction, use structured prompts specifying entity types (reactants, products, catalysts, solvents, conditions) and output format

- For fine-tuned models, utilize BioBERT or specialized chemical LLMs trained on annotated patent corpora like CheF [18]

- Apply constraint decoding to ensure output validity, incorporating chemical validation rules

Step 3: Entity Normalization and Validation

- Resolve lexical variations and synonyms through dictionary-based matching against chemical databases (PubChem, ChEBI)

- Validate chemical structures by converting extracted representations (names, SMILES) to canonical forms using toolkits like RDKit

- Implement structure-based validation to identify implausible entities or extraction errors

Table 2: Entity Types and Extraction Methods

| Entity Type | Extraction Method | Validation Approach | Common Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactants/Products | LLM + SMILES conversion | Structure validation, reaction balance checking | Partial structures, mixtures |

| Catalysts | Pattern-enhanced LLM | Catalyst database matching | Concentration thresholds |

| Solvents | Dictionary-guided LLM | Functional role verification | Co-solvents, mixtures |

| Conditions | Rule-constrained LLM | Physicochemical plausibility | Unit conversions, ranges |

| Yields | Numeric extraction LLM | Cross-validation with examples | Calculation methods |

Experimental results from the CheF dataset creation demonstrate that this protocol can extract chemical entities with 92% precision and 88% recall, significantly outperforming rule-based approaches which achieved 74% precision and 65% recall on the same patent set [18].

Relation Extraction Framework

Relationship extraction from chemical patents focuses on identifying meaningful connections between entities, particularly reaction pathways, conditions, and functional applications. The following framework provides a systematic approach:

Architecture Design The relation extraction pipeline employs a multi-stage architecture combining LLMs with structured knowledge:

Figure 1: Relation Extraction Workflow from Chemical Patents

Implementation Protocol

Step 1: Entity Pair Generation

- Generate candidate entity pairs using proximity-based heuristics (entities mentioned in same sentence or paragraph)

- Apply syntactic filters based on dependency parsing to identify semantically connected entities

- Use fine-tuned LLMs to identify potentially related entities based on contextual understanding

Step 2: Relation Classification

- Implement a multi-label classification approach to identify relationship types (reacts-with, catalyzes, dissolves-in, produces)

- Utilize prompt-based classification with few-shot examples for high flexibility

- Apply fine-tuned transformer models (BERT, SciBERT) for higher accuracy on specific relation types

- Incorporate chemical knowledge constraints to filter implausible relations

Step 3: Knowledge Graph Construction

- Transform extracted entities and relations into structured graph format

- Implement identity resolution to merge equivalent entities across extractions

- Enrich graph with additional attributes (conditions, yields, references)

- Apply consistency checks to identify and resolve conflicting information

Experimental validation on USPTO patents demonstrates that this framework achieves 85% F1 score on relation extraction tasks, with particularly strong performance on reaction participant identification (92% F1) and more moderate performance on complex condition relationships (76% F1) [14].

Experimental Evaluation

Performance Metrics and Benchmarks

Rigorous evaluation of LLM-based extraction systems requires comprehensive metrics spanning both technical performance and chemical validity. The following metrics provide a balanced assessment:

Technical Extraction Metrics

- Precision, Recall, and F1-score for entity and relation extraction

- Exact match accuracy for structured prediction tasks

- Slot error rate for template filling applications

Chemical Validity Metrics

- Chemical structure validity rate (percentage of extracted SMILES that represent valid structures)

- Reaction balance accuracy (atom mapping consistency between reactants and products)

- Condition plausibility (experimental conditions within physically possible ranges)

Application-oriented Metrics

- Synthesis planning utility (percentage of extractions sufficient for route planning)

- Database integration compatibility (structured data conforming to target schema)

- Human verification efficiency (reduction in manual curation time)

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Extraction Approaches

| Extraction Approach | Entity F1 | Relation F1 | Structure Validity | Reaction Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rule-based | 0.74 | 0.68 | 0.92 | 0.81 |

| Traditional ML | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.79 |

| LLM (Zero-shot) | 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.76 |

| LLM (Fine-tuned) | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.89 |

| LLM + Validation | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.98 | 0.95 |

Data derived from comparative studies on USPTO patents shows that fine-tuned LLMs significantly outperform other approaches, particularly when augmented with chemical validation [14] [18]. The incorporation of structural validation checks increases chemical validity metrics despite minor reductions in traditional extraction metrics.

Error Analysis and Limitations

Systematic error analysis reveals consistent patterns in LLM-based extraction failures:

Entity Extraction Errors

- Partial extraction: LLMs occasionally extract incomplete structures, particularly for complex molecules with multiple functional groups. This accounts for approximately 42% of entity errors in validation studies.

- Representation ambiguity: Different representation of the same chemical (e.g., salt forms, stereochemistry) leads to duplicate entities with minor variations (28% of errors).

- Context misinterpretation: LLMs sometimes confuse reactants, products, and intermediates when descriptions are ambiguous (19% of errors).

Relation Extraction Errors

- Condition attribution: Incorrect association of conditions (temperature, catalysts) with specific reaction steps (37% of relation errors).

- Complex pathway simplification: Oversimplification of multi-step reactions into single-step transformations (29% of errors).

- Negation misunderstanding: Failure to recognize described reactions that failed or are not recommended (18% of errors).

Domain-specific fine-tuning and the incorporation of chemical knowledge constraints have been shown to reduce these error categories by 35-60% in controlled evaluations [14].

Integration with Synthesis Planning

Knowledge Graph Construction

The transformation of extracted entities and relationships into structured knowledge graphs enables powerful applications in synthesis planning. The construction process involves:

Figure 2: Knowledge Graph Construction Pipeline

The resulting knowledge graph serves as a foundational resource for multiple synthesis planning applications:

- Reaction prediction: Identifying likely reaction outcomes based on extracted precedents

- Route optimization: Selecting optimal synthetic pathways based on accumulated patent knowledge

- Condition recommendation: Suggesting reaction conditions with highest reported yields

- Analogue design: Identifying structural modifications that preserve activity while improving synthesizability

Integration with systems like RSGPT demonstrates that knowledge graphs enriched with patent extractions can improve retrosynthesis prediction accuracy by 14% compared to models trained solely on structured reaction databases [16].

Case Study: RSGPT Integration

The RSGPT (RetroSynthesis Generative Pre-trained Transformer) framework provides a compelling case study in leveraging LLM-extracted data for synthesis planning. The integration follows a multi-stage process:

Data Preparation

- Extract reaction data from USPTO patents using LLM-based pipelines

- Convert extracted information to standardized reaction representations (SMILES, reaction SMILES)

- Apply atom mapping to establish reactant-product correspondence

- Filter and validate reactions based on chemical plausibility

Model Training

- Pre-train transformer architecture on large-scale synthetic reaction data (10+ billion datapoints) generated through RDChiral template application [16]

- Fine-tune on patent-extracted reactions using multi-task learning objectives

- Optimize with Reinforcement Learning with AI Feedback (RLAIF) to prioritize chemically plausible predictions

Performance Outcomes The integrated system demonstrates significant improvements in retrosynthesis planning:

- Top-1 accuracy of 63.4% on USPTO-50k benchmark, outperforming template-based (44.2%) and other template-free (53.7%) approaches [16]

- Enhanced performance on complex molecules with out-of-template structural features

- Improved condition recommendation accuracy through incorporation of extracted patent conditions

This case study illustrates the transformative potential of combining LLM-based extraction with specialized chemical AI systems for synthesis planning applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful implementation of LLM-based extraction systems for chemical patents requires a carefully curated toolkit of resources, datasets, and validation approaches. The following table summarizes essential components:

Table 4: Essential Resources for Chemical Patent Extraction

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Datasets | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | PubChem, ChEBI, SureChEMBL | Entity resolution, structure validation | 100M+ compounds, programmatic access |

| Reaction Databases | USPTO, ORD, Reaxys | Training data, evaluation benchmarks | Curated reactions, conditions, yields |

| NLP Libraries | spaCy, Hugging Face, NLTK | Text processing, model integration | Pretrained models, chemical extensions |

| Cheminformatics | RDKit, CDK, RDChiral | Structure manipulation, validation | SMILES processing, reaction handling |

| LLM Platforms | OpenAI GPT, Claude, Llama | Entity and relation extraction | API access, custom fine-tuning |

| Evaluation Frameworks | CheF dataset, USPTO benchmarks | Performance validation | Expert-annotated test sets |

Implementation considerations for research teams:

- Data Quality: The CheF dataset, comprising 631K molecule-function pairs extracted from patents using LLMs, provides a high-quality benchmark for training and evaluation [18]

- Validation Rigor: Incorporate multiple validation layers including structural checks (RDKit), reaction balancing (atom mapping), and cross-reference with established databases

- Pipeline Integration: Design extraction pipelines with modular architecture to accommodate evolving tooling and methodologies

Teams implementing the complete toolkit have reported 3-5x acceleration in data extraction workflows compared to manual curation, while maintaining or improving data quality for synthesis planning applications [14] [18].

The discovery and synthesis of new chemical compounds are fundamental to pharmaceutical and materials science research. Chemical patent documents serve as the primary and most timely source of information for new chemical discoveries, often containing the initial disclosure of novel compounds years before their publication in academic journals [19]. However, the rapidly expanding volume of chemical patents and their complex, unstructured text present significant challenges for manual information retrieval. Specialized Natural Language Processing (NLP) pipelines for Named Entity Recognition (NER) and Event Extraction have therefore become indispensable tools for automated knowledge extraction from chemical patents, enabling researchers to efficiently access and structure critical information for synthesis planning [19] [20].

These NLP technologies address a fundamental bottleneck in chemical research. The pharmaceutical industry faces an "unsolvable equation" of spiraling development costs and plummeting success rates, with the average drug taking 10-15 years and over $2.5 billion to develop, while success rates for candidates entering Phase I trials have fallen to just 6.7% [20]. Artificial intelligence, particularly NLP for chemical text mining, offers a promising solution to this productivity crisis by potentially generating $350-$410 billion in annual value for the pharmaceutical sector through accelerated discovery timelines and improved success rates [20]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the specialized NLP pipelines that make this possible, with particular focus on their application to chemical patent documents for synthesis planning research.

Domain-Specific Challenges in Chemical Patent Processing

Linguistic and Structural Complexities of Patent Documents

Chemical patents present unique challenges that distinguish them from standard scientific literature. As legal documents, patents are written with the dual purpose of disclosing inventions while simultaneously protecting intellectual property through broad claims, resulting in text that is often more exhaustive and structurally complex than typical research articles [19]. Key challenges include exceptionally long sentences that list multiple chemical compounds, complex syntactic structures in patent claims, domain-specific terminology, and a lexicon containing novel chemical terms that are difficult to interpret without specialized knowledge [19]. Quantitative analyses have shown that the average sentence length in patent corpora significantly exceeds that of general language use, creating substantial difficulties for syntactic parsing and information extraction [19].

Most publicly available chemical databases suffer from significant limitations for AI-driven drug discovery applications. Public repositories such as ChEMBL and PubChem, while invaluable for academic research, contain inherent structural limitations including publication bias toward positive results, incompleteness, lack of standardization, and absence of commercial context regarding synthesizability, formulation challenges, or cost of goods [20]. These databases are inherently retrospective, archiving what has already been discovered and published, often with substantial time lags between initial experimentation and public availability [20]. This creates a critical "garbage in, garbage out" problem where sophisticated AI models are trained on flawed or incomplete data, generating misleading results that waste significant resources in downstream experimental validation [20].

Table 1: Key Challenges in Chemical Patent Text Processing

| Challenge Category | Specific Issues | Impact on NLP Processing |

|---|---|---|

| Text Structure | Long sentence listings, complex claim syntax | Difficulties in syntactic parsing and entity relation mapping |

| Terminology | Domain-specific terms, novel chemical names | Limited generalizability of standard NLP models |

| Data Quality | Image quality issues, inconsistent formatting | Errors in optical chemical structure recognition (OCSR) |

| Information Distribution | Sparse signal localization across documents | "Needle-in-haystack" problem for relevant data |

| Multimodal Alignment | Disconnection between text and structure images | Challenges in correlating chemical entities with visual representations |

Core Annotation Schemes and Benchmark Datasets

The ChEMU Annotation Framework

The ChEMU (Cheminformatics Elsevier Melbourne University) evaluation lab, established as part of CLEF-2020, provides a comprehensive annotation framework specifically designed for chemical reaction extraction from patents [19]. This framework defines two complementary extraction tasks that form the foundation of modern chemical NLP pipelines:

Task 1: Named Entity Recognition involves identifying chemical compounds and their specific roles within chemical reactions, along with relevant experimental conditions. The annotation schema defines 10 distinct entity types that capture critical synthesis information [19]:

- REACTION_PRODUCT: A substance formed during a chemical reaction

- STARTING_MATERIAL: A substance consumed in the reaction that provides atoms to products

- REAGENT_CATALYST: Compounds added to cause or facilitate the reaction (including catalysts, bases, acids)

- SOLVENT: Chemical entities that dissolve solutes to form solutions

- OTHER_COMPOUND: Chemical compounds not falling into the above categories

- EXAMPLE_LABEL: Labels associated with reaction specifications

- TEMPERATURE: Reaction temperature conditions

- TIME: Reaction time parameters

- YIELD_PERCENT: Yield percentages

- YIELD_OTHER: Yields in units other than percentages

Task 2: Event Extraction focuses on identifying the individual steps within chemical reactions and their relationships with chemical entities. This involves detecting event trigger words (e.g., "added," "stirred") and determining their chemical entity arguments using semantic role labels adapted from the Proposition Bank: Arg1 for chemical compounds causally affected by events, and ArgM for adjunct roles linking triggers to temperature, time, or yield entities [19].

Several annotated corpora have been developed to support the training and evaluation of chemical NLP systems:

ChEMU Corpus: Comprises 1,500 chemical reaction snippets sampled from 170 English patent documents from the European Patent Office and United States Patent and Trademark Office, split into 70% training, 10% development, and 20% test sets with annotations in BRAT standoff format [19] [21].

DocSAR-200: A recently introduced benchmark of 200 scientific documents (98 patents, 102 research articles) specifically designed for evaluating Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) extraction methods, featuring 2,617 tables with sparse activity measurements and molecules of varying complexity [22].

Multimodal Chemical Information Datasets: Specialized collections such as the dataset comprising 210K structural images and 7,818 annotated text snippets from patents filed between 2010-2020, supporting the development of multimodal extraction systems [23].

Table 2: Quantitative Overview of Chemical Text Mining Benchmarks

| Dataset | Document Count | Document Types | Annotation Types | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMU | 1,500 snippets | Chemical patents | 10 entity types + event relations | Reaction-centric annotations from EPO/USPTO patents |

| DocSAR-200 | 200 documents | Patents & research articles | Molecular structures + activity data | Multi-lingual content, sparse activity signals |

| Multimodal Chemical Dataset | 7,818 text snippets + 210K images | Chemical patents | Chemical entities + structure images | Paired text and image data from 2010-2020 |

Technical Architectures for Chemical NER and Event Extraction

Hybrid NLP Pipeline Architecture

Modern approaches to chemical information extraction employ sophisticated hybrid architectures that combine multiple NLP strategies tailored to the peculiarities of patent text. The winning system in the CLEF 2020 ChEMU challenge demonstrated a comprehensive workflow incorporating several key innovations [24]:

This architecture addresses three fundamental challenges in chemical patent processing: (1) poor tokenization output for chemical and numeric concepts through domain-adapted tokenization; (2) lack of patent-specific language models through self-supervised pre-training on 20,000 additional patent snippets; and (3) uncovered domain knowledge through pattern-based rules and chemical dictionary matching [24]. The system achieved state-of-the-art performance with F1 scores of 0.957 for entity recognition and 0.9536 for event extraction in the ChEMU evaluation [24].

Advanced Multimodal Framework: Doc2SAR

For comprehensive Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) extraction, recent research has introduced the Doc2SAR framework, which addresses the limitations of both rule-based methods and general-purpose multimodal large language models through a synergistic, modular approach [22]:

Doc2SAR achieves an overall Table Recall of 80.78% on the DocSAR-200 benchmark, representing a 51.48% improvement over end-to-end GPT-4o, while processing over 100 PDFs per hour on a single RTX 4090 GPU [22]. The framework's effectiveness stems from its specialized component design:

Optical Chemical Structure Recognition (OCSR): A specialized module combining a Swin Transformer image encoder with a BART-style autoregressive decoder for SMILES generation, fine-tuned on 515 manually curated molecular image-SMILES pairs [22].

Molecular Coreference Recognition: A fine-tuned Multimodal Large Language Model (MLLM) that establishes correspondence between molecular structure images and their textual identifiers by analyzing layout context within a spatial window of 1.5× original dimensions [22].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Domain-Adapted Tokenization Methodology

Conventional tokenizers like WordPiece, designed for general text, perform poorly on chemical patent text due to unique patterns in chemical nomenclature and numeric expressions. The following protocol details the optimized tokenization process:

Chemical Compound Preservation: Implement rules to prevent splitting of chemical names (e.g., "4-(2-hydroxyethyl)morpholine") and SMILES strings (e.g., "C1=CC=CC=C1") into multiple tokens.