Benchmarking Machine Learning Models for Reaction Prediction: From Data Challenges to Real-World Applications in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current landscape, methodologies, and challenges in benchmarking machine learning models for chemical reaction prediction.

Benchmarking Machine Learning Models for Reaction Prediction: From Data Challenges to Real-World Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current landscape, methodologies, and challenges in benchmarking machine learning models for chemical reaction prediction. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of reaction prediction, examines diverse modeling approaches from global frameworks to data-efficient local models, and addresses critical troubleshooting areas like data scarcity and model interpretability. Furthermore, it offers a comparative review of validation frameworks and benchmarking tools essential for assessing model performance, generalizability, and practical utility in accelerating synthetic route design and optimization in biomedical research.

The Foundation of Reaction Prediction: Core Concepts, Data Landscapes, and Inherent Challenges

Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning (CASP) has emerged as a transformative technology in organic chemistry, drug discovery, and materials science. The core challenge it addresses is the retrosynthetic analysis of a target molecule—the process of recursively deconstructing it into simpler, commercially available starting materials by applying hypothetical chemical reactions [1]. This process is formalized as a search problem within a retrosynthetic tree, where the root node is the target molecule, OR nodes represent molecules, and AND nodes represent reactions that connect products to their reactants [2]. The combinatorial explosion of possible pathways makes exhaustive search computationally intractable, creating a problem space where Machine Learning (ML) has become indispensable for guiding the exploration toward synthetically feasible and efficient routes [3].

The integration of ML aims to overcome the limitations of early rule-based expert systems, which required extensive manual curation and exhibited brittle performance on novel molecular scaffolds [2]. Modern ML approaches automatically learn chemical transformations from large reaction databases, enabling the prediction of both single-step reactions and multi-step synthetic pathways with remarkable accuracy [2] [1]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of contemporary ML-driven CASP tools, evaluating their performance, algorithmic foundations, and applicability across different domains of synthetic chemistry.

Comparative Analysis of ML-Driven CASP Tools

Performance Benchmarking of CASP Systems

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics and algorithmic approaches of several prominent ML-driven CASP tools.

| Tool Name | Core Algorithm | Key Innovation | Reported Performance Advantage | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOT* [2] | LLM-integrated AND-OR Tree Search | Integrates LLM-generated pathways with systematic tree search. | Achieves competitive solve rates using 3-5× fewer iterations than other LLM-based approaches [2]. | Leverages pre-trained LLMs; relatively lower dependency on specialized reaction data. |

| AiZynthFinder [1] [3] | Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) | Template-based expansion policy with filter policy to remove unfeasible reactions. | A standard benchmark tool; performance highly dependent on the template set and filter accuracy [3]. | Relies on a curated database of reaction templates extracted from reaction databases. |

| RetroBioCat [4] | Best-First Search & Network Exploration | Expertly encoded reaction rules for biocatalysis and chemo-enzymatic cascades. | Effectively identifies promising biocatalytic pathways, validated against literature cascades [4]. | Utilizes a specialized, manually curated set of 99 biocatalytic reaction rules. |

| ReSynZ [5] | Monte Carlo Tree Search with Reinforcement Learning (AlphaGo Zero-inspired) | Self-improving model that trains on complete synthesis paths. | Demonstrates excellent predictive performance even with small reaction datasets (tens of thousands of reactions) [5]. | Designed for efficiency with smaller datasets (tens of thousands of reactions). |

Benchmarking Synthetic Accessibility Scores

Synthetic Accessibility (SA) scores are crucial ML-based heuristics used to pre-screen molecules or guide the search within CASP tools. The following table compares four key SA scores, assessed for their ability to predict the outcomes of retrosynthesis planning in tools like AiZynthFinder [3].

| SA Score | ML Approach | Basis of Prediction | Output Range | Primary Application in CASP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAscore [3] | Fragment Frequency & Complexity Penalty | Frequency of ECFP4 fragments in PubChem and structural complexity. | 1 (easy) to 10 (hard) | Pre-retrosynthesis filtering of virtual screening candidates. |

| SCScore [3] | Neural Network | Trained on 12 million Reaxys reactions to estimate number of synthesis steps. | 1 (simple) to 5 (complex) | Precursor prioritization within search algorithms (e.g., in ASKCOS). |

| RAscore [3] | Neural Network / Gradient Boosting | Trained on ChEMBL molecules labeled by AiZynthFinder's synthesizability. | N/A | Fast pre-screening for synthesizability specifically for AiZynthFinder. |

| SYBA [3] | Bernoulli Naïve Bayes Classifier | Trained on datasets of easy-to-synthesize (ZINC15) and hard-to-synthesize (generated) molecules. | N/A | Classifying molecules as easy or hard to synthesize during early-stage planning. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Benchmarking CASP Tools

A standardized assessment protocol, as utilized in critical evaluations of synthetic accessibility scores, provides a framework for comparing CASP tools objectively [3].

- Tool Configuration: Each CASP tool (e.g., AiZynthFinder, AOT*) is configured with its default parameters, including maximum search depth, the number of pathways to generate, and any specific policy settings.

- Test Set Curation: A diverse set of target molecules is selected from published benchmarks or literature examples of varying complexity. This set should include molecules from different structural classes and synthetic challenges.

- Search Tree Analysis: For each target molecule, the retrosynthetic search is executed. The resulting search tree is analyzed for key complexity parameters, including:

- The total number of nodes in the tree.

- The tree depth and width.

- The number of solved pathways (routes reaching buyable starting materials).

- Performance Metrics Calculation: The primary metrics for comparison are calculated:

- Solve Rate: The percentage of target molecules for which at least one viable synthetic route is found.

- Search Efficiency: The number of iterations or nodes expanded to find the first solution, or the time-to-solution.

- Route Quality: Assessment of the found routes based on the number of steps, availability of starting materials, and literature precedent for reactions used.

- SA Score Integration: To evaluate the utility of Synthetic Accessibility scores, the target molecules are first scored by tools like SCScore or RAscore. The correlation between these pre-synthesis scores and the eventual success or failure of the CASP tool is then calculated to determine the score's predictive power [3].

Protocol for Evaluating AOT*'s AND-OR Tree Search

The AOT* framework introduces a specific methodology that integrates Large Language Models (LLMs) with traditional tree search [2].

- Tree Formulation: The retrosynthetic problem is formulated as an AND-OR tree (\mathcal{T}=(\mathcal{V},\mathcal{E})), where OR nodes ((v \in \mathcal{V}{OR})) are molecules and AND nodes ((a \in \mathcal{V}{AND})) are reactions.

- LLM Pathway Generation: A generative function (g), powered by an LLM, takes a target molecule and a set of retrieved similar synthesis routes as context. It outputs one or more complete multi-step reaction pathways (p = \langle r1,...,rn \rangle).

- Atomic Pathway Mapping: Each generated pathway is atomically mapped onto the AND-OR tree structure. This step decomposes the coherent pathway into its constituent reactions (AND nodes) and intermediate molecules (OR nodes), which are integrated into the global tree.

- Reward-Guided Search: A mathematically sound reward assignment strategy is designed to evaluate nodes. The search then proceeds systematically, leveraging the tree structure to reuse intermediate molecules and pathways, avoiding redundant explorations.

- Validation: The framework is tested on standard synthesis benchmarks. Performance is measured by the solve rate and the number of iterations (LLM calls) required to find a solution, demonstrating a significant reduction in computational cost compared to non-integrated approaches [2].

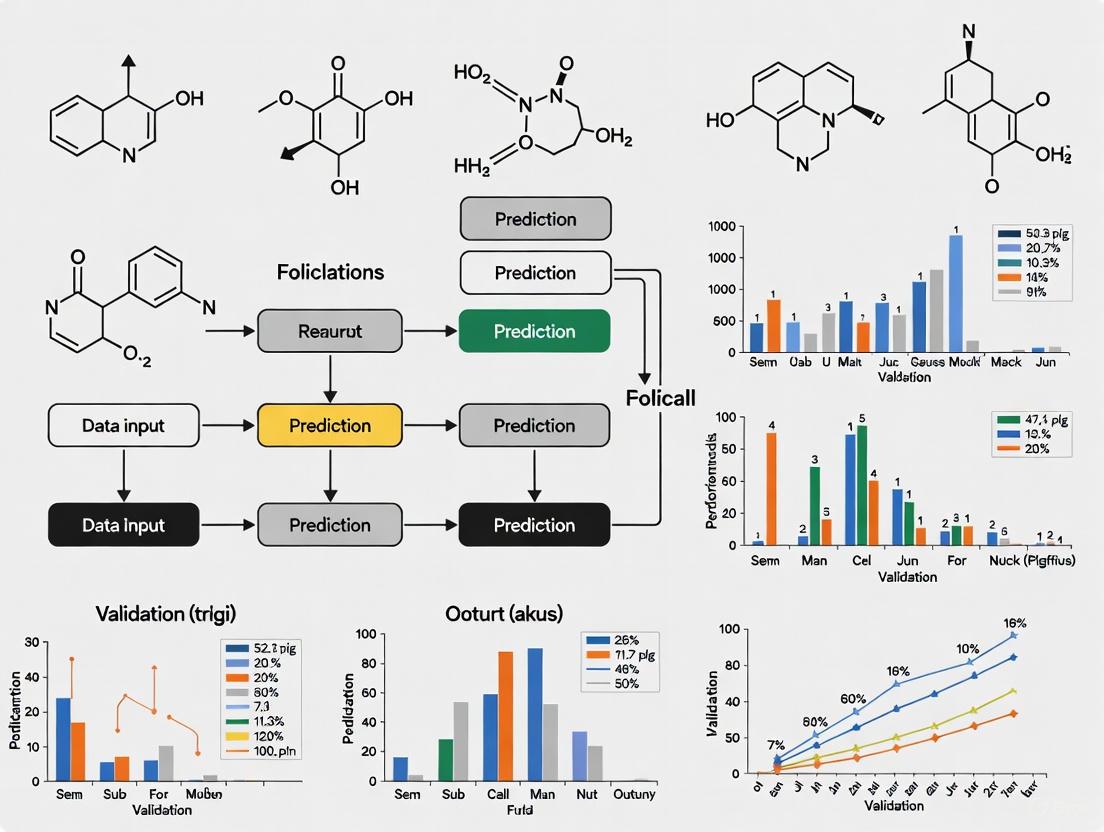

Diagram 1: AOT's LLM-Integrated AND-OR Tree Search Workflow.*

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Platforms

Successful implementation and benchmarking of ML-driven CASP require a suite of software tools and computational resources.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in CASP Research |

|---|---|---|

| AiZynthFinder [1] [3] | Open-Source CASP Platform | A flexible, modular tool for benchmarking retrosynthesis algorithms and expansion policies, widely used as a testbed. |

| RetroBioCat [4] | Web Application & Python Package | Specialized tool for designing biocatalytic and chemo-enzymatic cascades, accessible for non-experts. |

| RDKit [3] | Cheminformatics Library | Provides essential functions for handling molecules (e.g., fingerprint generation, SMILES parsing) and calculates SAscore. |

| SCScore & RAscore [3] | Specialized SA Score Models | Pre-trained models to quickly assess molecular complexity and retrosynthetic accessibility prior to full planning. |

| Reaction Databases (e.g., Reaxys) [3] | Data Source | Source of known reactions for training template-based or sequence-to-sequence ML models. |

The problem space of CASP is defined by the need to navigate exponentially large synthetic trees efficiently. ML has become the cornerstone of modern solutions, with different tools leveraging a diverse array of algorithms—from template-based MCTS and reinforcement learning to the integration of large language models. Benchmarking studies reveal that while core algorithms are crucial, auxiliary ML models like synthetic accessibility scores are vital for enhancing search efficiency. The ongoing self-improving capabilities of frameworks like ReSynZ and the hybrid symbolic-neural approach of AOT* point toward a future where CASP tools will not only replicate but potentially surpass human expertise in planning complex synthetic routes, significantly accelerating discovery across chemistry and pharmacology.

Chemical reaction databases are foundational to modern chemical research, serving as critical resources for fields ranging from drug discovery to materials science. For researchers applying machine learning (ML) to reaction prediction, the choice of database profoundly influences model performance, generalizability, and practical utility. These databases vary significantly in scope, data quality, and accessibility, presenting a complex ecosystem of public and proprietary resources. This guide provides an objective comparison of major chemical reaction databases, framed within the context of benchmarking machine learning models for reaction prediction. We summarize quantitative attributes, detail experimental methodologies for assessing data quality and ML performance, and visualize key workflows to aid researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the most appropriate data resources for their projects.

Database Landscape and Comparative Analysis

The landscape of chemical reaction databases includes large-scale public resources, manually curated specialized collections, and expansive commercial offerings. The table below provides a structured comparison of key databases based on their scope, size, and primary features relevant to ML research.

Table 1: Overview of Major Chemical Reaction Databases

| Database Name | Type/Access | Size (Reactions) | Key Features & Focus | Notable for ML |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAS Reactions [6] | Proprietary | > 150 million | Comprehensive coverage of journals and patents; curated by experts. | Breadth and authority of data; quality-controlled. |

| USPTO [7] [8] | Public | > 3 million (specific extract) | Reactions mined from US patents (1976-2016). | Largest public collection; widely used in ML research. |

| KEGG REACTION [9] | Public (Partially) | Not explicitly stated | Enzymatic reactions; integrated with metabolic pathways and genomics. | Manually curated; includes reaction class classification. |

| Chemical Reaction Database (CRD) [8] | Public | ~1.37 million | Enhanced USPTO data and academic literature; includes reagents/solvents. | Normalized data with calculated ratios for reaction components. |

| Reaxys [7] | Proprietary | > 55 million | Manually curated reactions from journals and patents. | High-quality data; cornerstone for deep-learning retrosynthesis. |

| Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) [10] | Public | > 100 million molecular snapshots | DFT-calculated 3D molecular properties and reaction pathways. | Designed for training Machine Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs). |

A critical challenge across most large-scale databases, particularly public ones mined from patents, is data quality. Imperfect text-mining and historical curation practices often result in unbalanced reactions, where co-reactants or co-products are omitted. One analysis found that less than 12% of single-step reactions in a Reaxys subset were balanced [7]. This imbalance poses a significant problem for training accurate ML models, as it violates fundamental laws of chemistry and can lead to physically implausible predictions.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking and Data Quality

To ensure reliable ML model performance, benchmarking against standardized datasets and addressing inherent data issues are essential. The following sections detail key experimental protocols for data rebalancing and yield prediction.

Protocol 1: Rebalancing Reactions with SynRBL

The SynRBL framework provides a novel, open-source solution for correcting unbalanced reactions, a common issue in automated data extraction [7].

- Objective: To automatically identify and add missing co-reactants and co-products to unbalanced chemical reactions, ensuring stoichiometric consistency.

- Methodology: The framework employs a dual-strategy approach:

- Rule-Based Method for Non-Carbon Compounds: Uses atomic symbols and counts to predict missing small molecules without carbon atoms (e.g., H₂O, HCl). This method achieved an accuracy exceeding 99% [7].

- MCS-Based Method for Carbon Compounds: For carbon imbalances, a Maximum Common Subgraph (MCS) technique aligns reactant and product structures to pinpoint non-aligned segments, which are then inferred as missing carbon-containing compounds. Accuracy for this method ranged from 81.19% to 99.33%, depending on reaction properties [7].

- Validation: The framework's overall efficacy was measured by its success rate (89.83% to 99.75%) and accuracy (90.85% to 99.05%) [7]. An applicability domain and a machine learning scoring function were also developed to quantify prediction confidence.

Diagram: SynRBL Framework Workflow for Reaction Rebalancing

Protocol 2: Yield Prediction with RS-Coreset

The RS-Coreset method addresses reaction optimization with limited data, a common constraint in laboratory settings [11].

- Objective: To predict reaction yields across a large reaction space using only a small subset of experimentally evaluated data points (as little as 2.5% to 5%).

- Methodology: This active learning approach iteratively constructs a representative subset (coreset) of the reaction space.

- Initialization: A small set of reaction combinations is selected randomly or based on prior knowledge, and their yields are experimentally evaluated.

- Iteration: The model cycles through three steps:

- Yield Evaluation: The chemist performs experiments on the selected combinations and records yields.

- Representation Learning: The model updates the reaction space representation using the new yield data.

- Data Selection: A max-coverage algorithm selects the next set of most informative reaction combinations to evaluate.

- Validation: On the public Buchwald-Hartwig coupling dataset (3,955 combinations), the model using only 5% of the data achieved promising results, with over 60% of predictions having absolute errors of less than 10% [11].

Diagram: RS-Coreset Iterative Workflow for Yield Prediction

Protocol 3: Transition State Prediction with React-OT

Predicting transition states is crucial for understanding reaction pathways and energy barriers.

- Objective: To rapidly and accurately predict the transition state structure of a chemical reaction.

- Methodology: The React-OT machine learning model reduces computational cost compared to quantum chemistry methods [12].

- Initial Guess: The model starts from an estimate of the transition state generated by linear interpolation, positioning each atom halfway between its reactant and product state.

- Refinement: The model refines this initial guess in about five steps, taking approximately 0.4 seconds per prediction.

- Performance: This approach is about 25% more accurate than a previous ML model and does not require a secondary confidence model, making it practical for high-throughput screening [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Beyond data and algorithms, practical computational research relies on a suite of software tools and resources. The table below details key resources mentioned in the cited research.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Reaction ML Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit [8] | Open-Source Cheminformatics | Provides computational chemistry functionality (e.g., reaction typing, descriptor calculation). | Used in the Chemical Reaction Database (CRD) to calculate reaction types. |

| RXNMapper [7] | Machine Learning Model | Performs atom-atom mapping for chemical reactions. | Cited as a tool that operates on unbalanced reaction data without direct correction. |

| Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) [10] | Public Dataset | >100 million DFT-calculated 3D molecular snapshots for training MLIPs. | Enables fast, accurate simulation of large systems and complex reactions. |

| USPTO Dataset [7] | Public Dataset | A large collection of reactions extracted from US patents. | Instrumental in developing reaction prediction, classification, and yield prediction models. |

| SynRBL Framework [7] | Open-Source Algorithm | Corrects unbalanced reactions in databases. | Used as a preprocessing step to improve data quality for downstream ML tasks. |

The choice of chemical reaction database is a fundamental decision that directly impacts the success of machine learning projects in reaction prediction. Proprietary databases like CAS Reactions and Reaxys offer unparalleled scale and curation, while public resources like USPTO and KEGG provide accessible, though often noisier, alternatives for method development. Emerging resources like OMol25 represent a shift towards pre-computed quantum mechanical data for training next-generation models. As the field advances, addressing data quality issues with tools like SynRBL and adopting data-efficient learning strategies like RS-Coreset will be crucial for developing robust, accurate, and generalizable ML models that can accelerate research and development in chemistry and drug discovery.

In the field of reaction prediction research, deep learning models are becoming indispensable tools for accelerating scientific discovery, particularly in areas like drug development. However, their adoption faces three central hurdles: data scarcity for many specialized chemical reactions, variable data quality from heterogeneous sources, and the inherent 'black box' problem, where the models' decision-making processes are opaque [13]. Benchmarking plays a crucial role in objectively assessing how different model architectures address these challenges under standardized conditions. This guide compares the performance of contemporary deep-learning models, providing researchers with a clear framework for evaluation based on recent benchmarks and methodologies.

Benchmarking Experimental Protocols

To ensure fair and meaningful comparisons, benchmarking initiatives in machine learning for reaction prediction follow rigorous experimental protocols. The core steps are visualized below, illustrating the workflow from data preparation to performance evaluation.

Diagram 1: Benchmarking Workflow for Reaction Prediction Models

The methodology can be broken down into several critical phases:

Data Collection and Curation: Benchmarks are constructed from large, publicly available chemical reaction databases. For instance, the ReactZyme benchmark was built from the SwissProt and Rhea databases, containing meticulously annotated enzyme-reaction pairs [14]. Similarly, the RXNGraphormer framework was pre-trained on a dataset of 13 million reactions [15]. This stage directly addresses data quality through rigorous annotation and cleaning.

Data Partitioning: A key strategy to test for data scarcity in specific domains is to use time-split partitioning or to hold out entire reaction classes. The ReactZyme benchmark, for example, is designed to evaluate a model's ability to predict enzymes for novel reactions and reactions for novel proteins, simulating real-world scenarios where models must generalize beyond their training data [14].

Model Training and Tuning: Models are trained according to their reported methodologies. This often involves a two-stage process of self-supervised pre-training on a large, general corpus of molecules (e.g., 97 million PubChem molecules for T5Chem [16]), followed by task-specific fine-tuning on the benchmark dataset. Hyperparameters are optimized via cross-validation.

Performance Evaluation: Trained models are evaluated on the held-out test set using task-specific metrics. The results are aggregated to produce the final benchmark scores, allowing for a direct comparison of different architectural approaches to the same problem.

Model Performance Comparison

The following tables summarize the performance of various state-of-the-art models on core reaction prediction tasks, highlighting their approaches to mitigating data scarcity and black-box interpretability.

Table 1: Comparative Performance on Key Reaction Prediction Tasks

| Model | Architecture | Key Tasks | Reported Performance | Approach to Data Scarcity | Interpretability Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ReactZyme [14] | Machine Learning (Retrieval Model) | Enzyme-Reaction Prediction | State-of-the-art on the ReactZyme benchmark (NeurIPS 2024) | Leverages the largest enzyme-reaction dataset to date; frames prediction as a retrieval problem for novel reactions. | Not explicitly stated in the context. |

| RXNGraphormer [15] | Graph Neural Network + Transformer | Reactivity/Selectivity Prediction, Synthesis Planning | State-of-the-art on 8 benchmark datasets. | Pre-training on 13 million reactions; unified architecture for multiple tasks enables cross-task knowledge transfer. | Generates chemically meaningful embeddings that cluster by reaction type without supervision. |

| T5Chem [16] | Text-to-Text Transformer (T5) | Reaction Yield Prediction, Retrosynthesis, Reaction Classification | State-of-the-art on 4 different task-specific datasets. | Self-supervised pre-training on 97M PubChem molecules; multi-task learning on a unified dataset (USPTO500MT). | Uses SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to provide functional group-level explanations for predictions. |

Table 2: Overview of Model Strategies Against Central Hurdles

| Central Hurdle | Model Strategies | Examples from Benchmarks |

|---|---|---|

| Data Scarcity | - Large-scale pre-training- Multi-task learning- Reformulating the problem (e.g., as retrieval) | - RXNGraphormer (13M reactions) [15]- T5Chem (97M molecules) [16]- ReactZyme (Retrieval approach) [14] |

| Data Quality | - Using curated, high-quality sources- Rigorous data preprocessing and validation | - ReactZyme (SwissProt & Rhea) [14]- T5Chem (uses RDKit for SMILES validation) [16] |

| 'Black Box' Problem | - Model-derived explanations (e.g., SHAP)- Intrinsic interpretability via embeddings | - T5Chem (SHAP for functional groups) [16]- RXNGraphormer (clustered embeddings) [15] |

Explaining the 'Black Box': XAI Techniques

Explainable AI (XAI) techniques are essential for building trust and providing mechanistic insights into model predictions. The following diagram outlines a standard workflow for applying XAI in a chemical context.

Diagram 2: Workflow for Explaining Model Predictions

As shown in Diagram 2, a specific input (e.g., a reaction SMILES string) is fed into the trained model to get a prediction. An XAI method is then employed to attribute the prediction to features of the input. For example:

- SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations): This is a prominent method used to interpret complex models. It works by calculating the marginal contribution of each input feature (e.g., the presence of a specific functional group in a molecule) to the final prediction [13] [16]. In practice, frameworks like T5Chem have successfully adapted SHAP to provide explanations at the functional group level, helping chemists understand which parts of a molecule are most critical for a predicted outcome, such as reaction yield [16].

Successful benchmarking and model development rely on a suite of software tools and data resources. The table below details key "research reagent solutions" essential for this field.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for Reaction Prediction Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Central Hurdles |

|---|---|---|---|

| USPTO Datasets [15] [16] | Data | Provides hundreds of thousands of known chemical reactions for training and testing. | Mitigates Data Scarcity; quality can be variable, impacting Data Quality. |

| Rhea & SwissProt [14] | Data | Curated databases of enzymatic reactions and proteins. | Provides high-Quality data for specialized (enzyme) reaction prediction. |

| RDKit [16] | Software | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit. | Used for molecule manipulation, SMILES validation (improving Data Quality), and descriptor calculation. |

| SHAP [13] [16] | Software | A game-theoretic approach to explain model outputs. | Directly addresses the 'Black Box' Problem by providing post-hoc explanations. |

| Hugging Face Transformers [16] | Software | Library providing thousands of pre-trained models (e.g., T5, BERT). | Accelerates model development, reducing the resource cost of tackling Data Scarcity via transfer learning. |

| Benchmarking Suites (e.g., ReactZyme) [14] | Framework | Standardized tests for specific prediction tasks (e.g., enzyme-reaction pairs). | Provides a level playing field to objectively assess how well models overcome all three central hurdles. |

Key Insights and Future Directions

The current benchmarking landscape reveals that no single model architecture universally dominates. Instead, the choice of model often depends on the specific task and which of the central hurdles is most critical. Transformer-based models like T5Chem excel in flexibility and benefit from transfer learning, providing a strong defense against data scarcity [16]. Hybrid models like RXNGraphormer leverage the strengths of both graph networks and transformers, showing state-of-the-art performance across a wide range of tasks and generating intrinsically interpretable features [15]. The field is increasingly moving toward unified models trained on multiple tasks, as evidence suggests this multi-task approach leads to more robust and generalizable models [15] [16].

Looking ahead, several trends are emerging. The creation of larger, more specialized, and higher-quality datasets will continue to be a priority. Furthermore, the integration of XAI techniques like SHAP directly into the model development and validation workflow will become standard practice, transforming the "black box" into a tool for generating novel, testable chemical hypotheses [13] [16]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the ongoing development of these benchmarks ensures that the selection of a reaction prediction model can be a data-driven decision, balancing performance with interpretability and reliability.

Methodologies in Action: From Global Models to Data-Efficient Learning Strategies

In the field of machine learning for reaction prediction, researchers and drug development professionals face a fundamental trade-off: whether to employ global models trained on extensive, diverse datasets or local models refined for specific chemical domains. This choice balances two competing objectives: broad applicability against targeted optimization. Global models leverage large-scale data to generalize across wide chemical spaces, while local models sacrifice some applicability domain size to achieve higher accuracy within narrower, well-defined contexts [17]. The decision between these approaches has significant implications for predictive performance, resource allocation, and ultimately, the success of drug discovery programs.

This guide objectively compares these modeling paradigms within the context of benchmarking machine learning models for reaction prediction research. We present standardized evaluation methodologies, quantitative performance comparisons, and practical implementation frameworks to inform model selection strategies. By examining experimental data across multiple studies, we provide evidence-based insights into how global and local models perform under different conditions, enabling researchers to make informed decisions based on their specific project requirements, available data resources, and accuracy targets.

Conceptual Framework: Defining Global and Local Modeling Approaches

Core Characteristics and Trade-offs

The fundamental distinction between global and local models lies in their applicability domains and training data scope. Global models are trained on extensive, diverse datasets encompassing broad chemical spaces, enabling them to make predictions for a wide variety of structures and reaction types. In contrast, local models specialize in specific chemical subspaces—such as particular scaffold types or reaction classes—by leveraging more focused, homogeneous training data [17].

This difference in scope creates a characteristic trade-off between applicability domain size and predictive accuracy, as illustrated in Figure 1. While global models can handle more diverse inputs, this broader capability often comes at the expense of reduced accuracy for any specific chemical subspace. Local models, by focusing on narrower domains, typically achieve higher accuracy within their specialized areas but may fail completely when presented with structures outside their training distribution [17].

Figure 1. Model Characteristics Comparison - This diagram visualizes the fundamental trade-offs between global and local models across five key dimensions.

Model Performance in Different Contexts

Experimental comparisons demonstrate how the performance differential between global and local models varies depending on the test set composition. When evaluated on randomly selected external test sets representing broad chemical space, global models typically outperform local models due to their wider training distribution. However, this relationship reverses when testing on specialized scaffold analogues, where local models demonstrate superior accuracy despite being trained on significantly less data [17].

The performance advantage of local models becomes particularly pronounced in scenarios involving:

- Specific scaffold families with distinct chemical properties

- Specialized reaction types with well-defined mechanisms

- Analog series in medicinal chemistry optimization

- Transfer learning scenarios where local models can be fine-tuned on specific domains [17]

Experimental Benchmarking: Methodologies for Model Evaluation

Cross-Dataset Generalization Framework

Robust evaluation of model performance requires standardized benchmarking frameworks that test generalization capabilities beyond single-dataset validation. The IMPROVE benchmark provides a comprehensive methodology for assessing cross-dataset generalization in drug response prediction models [18] [19]. This framework incorporates five publicly available drug screening datasets (CCLE, CTRPv2, gCSI, GDSCv1, GDSCv2), six standardized DRP models, and scalable workflows for systematic evaluation [18].

The benchmark introduces specialized metrics that quantify both absolute performance (predictive accuracy across datasets) and relative performance (performance drop compared to within-dataset results), enabling a more comprehensive assessment of model transferability [18]. This approach reveals substantial performance drops when models are tested on unseen datasets, highlighting the importance of rigorous generalization assessments beyond conventional cross-validation.

Workflow for Model Comparison Studies

Experimental comparisons between global and local models require careful study design to ensure fair evaluation. The workflow illustrated in Figure 2 demonstrates a standardized approach for such comparisons [17]:

Figure 2. Model Comparison Workflow - Standardized experimental design for comparing global and local model performance.

This methodology ensures that:

- Both models are evaluated on identical test sets representing different chemical spaces

- The scaffold cluster has limited similarity to the global set (maximum Tanimoto similarity: 0.784)

- Local models are trained on significantly less data (16x fewer training examples)

- Performance is assessed on both broad chemical space and specialized analogues [17]

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Cross-Dataset Generalization Results

Table 1. Cross-Dataset Generalization Performance of Drug Response Prediction Models [18]

| Source Dataset | Target Dataset | Best Performing Model | Generalization Gap | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTRPv2 | CCLE | GraphDRP | -12.3% | Performance drop consistent across models |

| CTRPv2 | gCSI | RESP | -15.7% | CTRPv2 identified as most effective source dataset |

| GDSCv1 | CTRPv2 | CARE | -18.2% | Substantial variance in model transferability |

| CCLE | GDSCv2 | GraphDRP | -22.4% | No single model consistently outperforms others |

| gCSI | CCLE | RESP | -14.9% | Dataset characteristics significantly impact transfer |

The benchmarking results reveal several critical patterns. First, all models experience substantial performance drops when applied to unseen datasets, with generalization gaps ranging from 12-22% depending on the dataset pair [18]. Second, CTRPv2 emerges as the most effective source dataset for training, yielding higher generalization scores across multiple target datasets [18]. Third, no single model consistently outperforms all others across every dataset pair, suggesting that model performance is context-dependent [18].

Local vs. Global Model Performance

Table 2. Performance Comparison of Local and Global Models on Different Test Sets [17]

| Test Set Composition | Global Model Performance | Local Model Performance | Performance Delta | Training Data Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random External Test Set | 0.84 AUC | 0.76 AUC | +0.08 Global | 16:1 |

| Scaffold Analogues | 0.79 AUC | 0.87 AUC | +0.08 Local | 16:1 |

| Updated Scaffold Analogues | 0.82 AUC | 0.91 AUC | +0.09 Local | 16:1 |

The comparative analysis demonstrates the context-dependent nature of model performance. Global models outperform on randomly selected external test sets, achieving 0.84 AUC compared to 0.76 AUC for local models [17]. However, this relationship reverses when evaluating on scaffold analogues, where local models achieve 0.87 AUC despite being trained on 16x less data [17]. After retraining with additional scaffold analogues, both models show improved performance, but local models maintain their advantage (0.91 AUC vs. 0.82 AUC) [17].

Implementation Protocols: From Benchmarking to Application

Standardized Evaluation Workflow

Implementing rigorous model evaluation requires standardized protocols. The following workflow provides a systematic approach for comparing global and local models:

Data Preparation and Splitting

Model Training and Configuration

- Train global models on diverse, large-scale datasets

- Train local models on focused, homogeneous datasets

- Utilize consistent feature representations (e.g., ECFP fingerprints, molecular descriptors) [18]

Cross-Dataset Evaluation

- Test models on both within-dataset and cross-dataset splits

- Evaluate on both broad chemical space and specialized analogues

- Employ multiple metrics (AUC, RMSE, R²) for comprehensive assessment [18]

Performance Analysis and Interpretation

- Calculate generalization gaps (within-dataset vs. cross-dataset performance)

- Identify performance patterns across different chemical domains

- Assess model calibration and uncertainty estimation

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3. Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Reaction Prediction Studies

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Model Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCLE Dataset | Biological Data | Drug response screening in cancer cell lines | Training and benchmarking data for DRP models [18] |

| CTRPv2 Dataset | Biological Data | Large-scale cancer drug sensitivity profiling | Preferred source dataset for global models [18] |

| GDSCv1/v2 Datasets | Biological Data | Drug sensitivity in cancer cell lines | Cross-dataset generalization testing [18] |

| gCSI Dataset | Biological Data | Dose-response screening data | Independent validation of model performance [18] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics | Molecular fingerprint generation | Creates standardized drug representations [18] |

| SMILES Representation | Chemical Notation | Text-based molecular structure encoding | Input for transformer-based models [20] |

| IMPROVE Framework | Software Tool | Standardized benchmarking pipeline | Ensures consistent model evaluation [18] |

| BERT Architecture | Deep Learning Model | Chemical reaction representation learning | Foundation for global yield prediction models [20] |

The experimental evidence demonstrates that the choice between global and local models depends fundamentally on the specific application context and data environment. Global models are preferable when predicting for diverse chemical spaces, when data is abundant and representative, and when the primary goal is broad applicability across multiple domains [18] [17]. Local models excel in scenarios involving specific scaffold families, specialized reaction types, or when higher accuracy is required for a well-defined chemical subspace [17].

For most practical applications in drug discovery, a hybrid approach delivers optimal results. This strategy employs global models for initial screening and compound prioritization, while leveraging local models for lead optimization and specific scaffold families. Additionally, transfer learning techniques that pre-train on global data then fine-tune on domain-specific data offer a promising middle ground, balancing broad applicability with targeted optimization.

The benchmarking results further suggest that cross-dataset evaluation should become a standard practice in model assessment, as within-dataset performance often provides an overly optimistic view of real-world applicability [18]. By strategically selecting and combining global and local approaches based on specific project needs, researchers can maximize predictive performance while effectively managing the inherent trade-offs between broad applicability and targeted optimization.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Architectural Overview of RXNGraphormer

- Performance Benchmarking

- Experimental Protocols in Model Evaluation

- Essential Research Toolkit

The pursuit of universal chemical predictors represents a central challenge at the intersection of artificial intelligence and chemistry. For years, a significant methodological divergence has existed between models designed for numerical regression tasks, such as reaction yield prediction, and those built for sequence generation tasks, like synthesis planning [15] [21]. This division has hindered the development of versatile and robust AI tools for chemical research. The emergence of unified, pre-trained frameworks marks a paradigm shift, aiming to bridge this gap through architectures capable of handling multiple task types from a single foundational model. This guide objectively explores one such framework, RXNGraphormer, benchmarking its performance against established alternatives and detailing the experimental protocols essential for its evaluation within the broader context of benchmarking machine learning models for reaction prediction research.

RXNGraphormer is designed as a unified deep learning framework that synergizes graph neural networks (GNNs) and Transformer models to address both reaction performance prediction and synthesis planning within a single architecture [15] [21] [22]. Its core innovation lies in its hybrid design, which processes chemical information at multiple levels.

The following diagram illustrates the unified architecture and workflow of RXNGraphormer for cross-task prediction:

The architecture operates on a two-stage transfer learning paradigm. Initially, the model is pre-trained on a massive corpus of 13 million chemical reactions as a classifier to learn fundamental bond transformation patterns [15] [22]. This pre-trained model is then fine-tuned for specific downstream tasks using smaller, task-specific datasets. For regression tasks like yield prediction, a dedicated regression head is used, while synthesis planning tasks employ a sequence generation head [22]. This approach allows the model to leverage general chemical knowledge acquired during pre-training and apply it efficiently to specialized tasks, even with limited data.

Performance Benchmarking

A critical step in evaluating any model is a rigorous comparison of its performance against established benchmarks and alternatives. The table below summarizes RXNGraphormer's performance across various reaction prediction tasks as reported in the literature.

Table 1: Benchmark Performance of RXNGraphormer on Reaction Prediction Tasks

| Task Category | Specific Task / Dataset | Reported Performance | Key Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactivity Prediction | Buchwald-Hartwig C-N Coupling [15] [22] | State-of-the-art (Specific metrics not provided in search results) | Outperformed previous models |

| Reactivity Prediction | Suzuki-Miyaura C-C Coupling [15] [22] | State-of-the-art (Specific metrics not provided in search results) | Outperformed previous models |

| Selectivity Prediction | Asymmetric Thiol Addition [15] [22] | State-of-the-art (Specific metrics not provided in search results) | Outperformed previous models |

| Synthesis Planning | USPTO-50k (Retrosynthesis) [15] [22] | State-of-the-art accuracy | Achieved top performance on standard benchmark |

| Synthesis Planning | USPTO-480k (Forward-Synthesis) [15] [22] | State-of-the-art accuracy | Achieved top performance on standard benchmark |

When compared to other model types, it is essential to consider their performance under realistic, out-of-distribution (OOD) conditions, which is a more accurate measure of real-world utility than standard random splits.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Reaction Prediction Model Architectures

| Model Architecture | Representative Example | Key Strengths | Key Limitations / Biases |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES-based Transformer | Molecular Transformer [23] | High accuracy on in-distribution benchmark data (e.g., ~90% on USPTO) [23] | Performance drops on OOD splits (e.g., ~55% accuracy on author splits); prone to "Clever Hans" exploits using dataset biases [23] [24] |

| Graph-based Models | Various GNN Models [24] | Directly encodes molecular structure | Also susceptible to performance degradation on OOD data, similar to sequence models [24] |

| Unified Graph+Transformer | RXNGraphormer [15] | State-of-the-art on multiple ID benchmarks; generates chemically meaningful embeddings that cluster by reaction type without supervision [15] | Specific OOD performance not detailed in available sources; requires significant computational resources for pre-training |

The performance of models like the Molecular Transformer can be overly optimistic when evaluated on standard random splits of datasets like USPTO. Studies show that when a more realistic split is used—such as separating reactions by author or patent document—top-1 accuracy can drop significantly, from 65% to 55% [24]. This highlights the importance of rigorous benchmarking protocols that challenge models to generalize beyond their training distribution.

Experimental Protocols in Model Evaluation

To ensure fair and meaningful comparisons between different reaction prediction models, researchers should adhere to standardized experimental protocols. The following workflow outlines key stages for a robust evaluation, incorporating insights from critical analyses of model performance.

Data Sourcing and Curation: Models are typically trained on large-scale reaction datasets extracted from patent literature, such as USPTO or the proprietary Pistachio dataset [23] [24]. For unified models like RXNGraphormer, a massive and diverse pre-training dataset (e.g., 13 million reactions) is crucial for learning general chemical patterns [15].

Data Splitting Strategies: The choice of how to split data into training, validation, and test sets profoundly impacts performance assessment.

- Random Splits: The conventional approach, but now known to be overoptimistic as it can leak structurally similar reactions from the same document into both training and test sets [24].

- Stratified Splits: More rigorous evaluations use splits that control for dataset structure. Document splits ensure all reactions from a single patent document are in the same set, while author splits group all reactions by the same inventor. These mimic real-world scenarios where a model encounters entirely new chemical projects and are considered more realistic [24].

- Time Splits: This prospective evaluation trains models on reactions published up to a certain year and tests them on reactions from later years, directly simulating real-world deployment and testing the model's ability to generalize to new chemistry [24].

Model Training and Fine-tuning: For pre-trained models like RXNGraphormer, the standard protocol involves a two-stage process. First, the model undergoes pre-training on a large, general reaction corpus, often framed as a reaction classification task. Subsequently, the model is fine-tuned on a smaller, task-specific dataset (e.g., for yield prediction or retrosynthesis) [15] [22].

Evaluation Metrics: The standard metric for product prediction and synthesis planning is Top-k accuracy, which measures whether the ground-truth product or reactant appears in the model's top-k predictions [24]. For regression tasks like yield prediction, metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) or Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) are used. For unified models, performance is assessed across all supported task types to verify cross-task competence [15].

Interpretation and Bias Detection: Beyond raw accuracy, tools like Integrated Gradients can attribute predictions to specific parts of the input molecules, helping to validate if the model is learning chemically rational features [23]. Analyzing the model's latent space to see if reactions cluster meaningfully (e.g., by reaction type) provides additional validation, as seen with RXNGraphormer's embeddings [15]. It is also critical to test for "Clever Hans" predictors, where a model exploits spurious correlations in the training data rather than learning underlying chemistry [23].

Essential Research Toolkit

For researchers seeking to implement or benchmark unified frameworks for reaction prediction, the following tools and resources are essential.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Relevance to Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|

| USPTO Dataset | A standard benchmark dataset containing organic reactions extracted from U.S. patents. | Serves as the primary source for training and evaluating models on synthesis planning tasks [23] [22]. |

| Pistachio Dataset | A large, commercially curated dataset of chemical reactions from patents. | Used for rigorous benchmarking, especially for creating challenging out-of-distribution splits [24]. |

| RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit. | Used for parsing SMILES strings, generating molecular fingerprints, and handling molecular graph operations during data preprocessing [22]. |

| Pre-trained RXNGraphormer Models | Foundation models pre-trained on 13 million reactions, available for download. | Provides a starting point for transfer learning, allowing researchers to fine-tune on specific tasks without the cost of large-scale pre-training [15] [22]. |

| Integrated Gradients | An interpretability algorithm for explaining model predictions. | Used to attribute a model's output to its inputs, validating that predictions are based on chemically relevant substructures [23]. |

| Debiased Benchmark Splits | Data splits designed to prevent overfitting to document-specific patterns. | Crucial for obtaining a realistic estimate of model performance on novel chemistry. Includes document, author, and time-based splits [23] [24]. |

The application of machine learning (ML) in chemical reaction prediction and optimization represents a paradigm shift in research methodology. However, a significant challenge persists: the scarcity of high-quality, large-scale experimental data in most laboratories, which stands in stark contrast to the data-hungry nature of conventional ML models. This benchmarking guide objectively compares two principal strategies—transfer learning (TL) and active learning (AL)—designed to overcome data limitations. These strategies mirror the chemist's innate approach of applying prior knowledge and designing informative next experiments. This guide provides a comparative analysis of their performance, experimental protocols, and implementation requirements, serving as a reference for researchers and development professionals in selecting appropriate methods for their specific constraints and goals.

Core Strategy Definitions and Workflows

Transfer Learning

Transfer Learning (TL) is a machine learning technique where a model developed for a source task is repurposed as the starting point for a model on a target task. The core assumption is that knowledge gained from solving one problem (typically with large datasets) can be transferred to a related, but distinct, problem (often with limited data) [25] [26]. In chemical terms, this is analogous to a chemist applying knowledge from a well-understood C-N coupling reaction to a new, unexplored C-N coupling system.

Active Learning

Active Learning (AL) is a cyclical process where a learning algorithm interactively queries a user (or an experiment) to label new data points with the desired outputs. Instead of learning from a static, randomly selected dataset, the model actively selects the most "informative" or "uncertain" data points to be experimentally evaluated next, thereby maximizing the value of each experiment and reducing the total number of experiments required [27] [28].

Combined Workflow: Active Transfer Learning

For challenging prediction tasks, combining TL and AL into an Active Transfer Learning strategy can be highly effective. This hybrid approach uses a model pre-trained on a source domain to guide the initial exploration in the target domain, after which an active learning loop takes over to refine the model with targeted experiments [29]. The logical relationship and workflow of this powerful combination are detailed in the diagram below.

Diagram 1: Active transfer learning workflow combines initial knowledge transfer with iterative experimentation.

Performance Benchmarking and Quantitative Comparison

Predictive Accuracy and Data Efficiency

The table below summarizes the performance of TL and AL strategies across various chemical reaction prediction tasks, as reported in the literature.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarking of TL and AL Strategies

| Strategy | Application Context | Reported Performance | Data Efficiency | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer Learning | Photocatalytic [2+2] cycloaddition [30] | R² = 0.27 (Conventional ML) → Improved with TL | Effective with only ~10 training data points | R² Score |

| Transfer Learning | Pd-catalyzed C–N cross-coupling [29] | ROC-AUC > 0.9 for mechanistically similar nucleophiles | Leveraged ~100 source data points | ROC-AUC |

| Active Learning | General reaction outcome prediction [28] | Reached target accuracy faster than passive learning | Reduced experiments by 50-70% | Area Under Curve (AUC) / Time |

| Active Learning (RS-Coreset) | Buchwald-Hartwig coupling [11] | >60% predictions had <10% error | Used only 5% of full reaction space (~200 points) | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) |

| Active Transfer Learning | Challenging Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling [29] | Outperformed random selection and pure TL | Improved model with iterative queries | ROC-AUC |

Computational and Experimental Resource Requirements

Beyond predictive accuracy, the resource footprint is a critical benchmarking parameter for practical adoption.

Table 2: Comparison of Resource and Implementation Requirements

| Requirement | Transfer Learning | Active Learning | Active Transfer Learning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior Data Need | High (Large source domain dataset) | Low (Can start from scratch or small set) | High (Source domain dataset required) |

| Initial Experimental Cost | Low (Leverages prior data) | Moderate (Requires initial batch of experiments) | Low (Leverages prior data) |

| Computational Overhead | Moderate (Model pre-training) | Low to Moderate (Iterative model updating) | High (Pre-training + iterative updating) |

| Expertise for Implementation | Moderate (Domain alignment critical) | Moderate (Query strategy design key) | High (Both TL and AL components) |

| Handling Domain Shifts | Poor (Fails with unrelated domains) | Good (Adapts to the target domain) | Excellent (Adapts after initial transfer) |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol: Domain Adaptation for Photocatalysis

This protocol is based on the study "Transfer learning across different photocatalytic organic reactions" [30].

- Source Domain Data Curation: Collect quantitative reaction yield data for 100 organic photosensitizers (OPSs) in nickel/photocatalytic C–O, C–S, and C–N cross-coupling reactions.

- Descriptor Generation: For each OPS, compute a set of molecular descriptors. This includes:

- DFT Descriptors: Perform DFT calculations (B3LYP-D3/6-31G(d) level) to obtain HOMO/LUMO energies (EHOMO, ELUMO). Use TD-DFT (M06-2X/6-31+G(d) level) to calculate vertical excitation energies for the lowest singlet (E(S1)) and triplet (E(T1)) states, oscillator strength (f(S1)), and the difference in dipole moments between ground and excited states (ΔDM).

- SMILES-based Descriptors: Generate alternative descriptor sets (e.g., RDKit, MACCSKeys, Mordred, Morgan Fingerprint) from molecular SMILES strings. Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce dimensionality.

- Target Domain Data: Collect a smaller dataset of reaction yields for the same OPSs in the target reaction: a photocatalytic [2+2] cycloaddition of 4-vinylbiphenyl.

- Model Training and Transfer:

- Train a baseline Random Forest (RF) model using only the small target dataset. Evaluate performance via R² on a held-out test set.

- Implement the TrAdaBoost.R2 algorithm, an instance-based domain adaptation method. Use the source domain data (cross-coupling reactions) as the transfer source and the target domain data ([2+2] cycloaddition) for model adaptation.

- Compare the R² scores of the baseline model versus the transfer-learned model to quantify improvement.

Protocol: Active Learning for Reaction Yield Prediction

This protocol is based on the "RS-Coreset" framework for active representation learning [11].

- Reaction Space Definition: Define the combinatorial space of all possible reaction conditions. For example, a space of 5760 combinations = 15 electrophiles × 12 nucleophiles × 8 ligands × 4 solvents.

- Initial Random Sampling: Select an initial small batch (e.g., 1-2% of the total space) of reaction combinations uniformly at random. Perform high-throughput experimentation (HTE) to obtain reaction yields for these combinations.

- Iterative Active Learning Loop: Repeat for a fixed number of iterations or until a performance threshold is met:

- Representation Learning: Train a graph neural network (GNN) or other representation model on all collected yield data to learn a feature representation for the entire reaction space.

- Coreset Selection (Query): Using the learned representation, run a maximum coverage algorithm (e.g., a greedy k-centers algorithm) to select the next batch of reaction combinations that are most diverse and representative of the entire space. This is the RS-Coreset.

- Yield Evaluation: Conduct experiments to obtain yields for the newly selected RS-Coreset combinations.

- Model Update: Update the predictive model with the newly acquired data.

- Final Prediction: Use the final model to predict yields for all remaining unmeasured combinations in the reaction space. Validate predictions with a subset of hold-out experiments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

This section details key computational and experimental "reagents" essential for implementing the strategies discussed in this guide.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Data-Efficient ML

| Reagent / Solution | Type | Primary Function | Exemplary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| TrAdaBoost.R2 | Algorithm | Instance-based transfer learning that re-weights source instances during boosting. | Improving photocatalytic activity prediction with limited target data [30]. |

| RS-Coreset | Algorithm | Active learning method that selects diverse, representative data points from a reaction space. | Predicting yields for thousands of reaction combinations with <5% experimental load [11]. |

| DeepReac+ | Software Framework | GNN-based model with integrated active learning for reaction outcome prediction. | Universal quantitative modeling of yields and selectivities with minimal data [28]. |

| Chemprop | Software Framework | Message-passing neural network for molecular property prediction; supports TL and delta learning. | Predicting high-level activation energies using lower-level computational data [31]. |

| Molecular Transformer | Architecture & Model | Transformer model fine-tuned for chemical reaction tasks, including polymerization. | Predicting polymerization reactions and retro-synthesis via transfer learning [32]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) | Platform | Automated platform for conducting hundreds to thousands of parallel reactions. | Generating dense, consistent datasets for training and validating AL/TL models [29] [11]. |

This benchmarking guide demonstrates that both transfer learning and active learning are powerful, validated strategies for overcoming the data bottleneck in chemical reaction ML. Transfer learning excels when substantial, high-quality data from a mechanistically related source domain exists, providing a significant head start. Active learning is superior for efficiently exploring a new, complex reaction space from the ground up, maximizing information gain per experiment. The emerging paradigm of Active Transfer Learning combines the strengths of both, offering a robust framework for tackling the most challenging reaction development problems.

The choice of strategy depends on the specific research context: the availability of prior data, the complexity of the target space, and the experimental budget. As these methodologies mature and become more integrated into automated discovery workflows, they will undoubtedly play a central role in accelerating the design and optimization of new reactions and molecules.

Accurately predicting reaction outcomes is a cornerstone of advancing synthetic chemistry, drug development, and materials science. For researchers and drug development professionals, the ability to forecast yield and selectivity reliably using machine learning (ML) can dramatically reduce the costs and time associated with exploratory experimentation. This guide provides an objective comparison of contemporary ML models by examining key case studies, detailing their experimental protocols, and benchmarking their performance against one another and traditional methods. The evaluation is framed within the broader thesis of establishing robust benchmarks for reaction prediction research, with a focus on practical applicability and performance under data constraints common in real-world research settings.

Performance Benchmarking of Predictive Models

The table below summarizes the core performance metrics of several recently developed machine learning models for reaction prediction, providing a baseline for objective comparison.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Reaction Prediction Models

| Model Name | Core Methodology | Key Tasks | Reported Performance | Data Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ReactionT5 [33] | Transformer-based model with two-stage pre-training (compound + reaction) on the Open Reaction Database. | Product Prediction, Retrosynthesis, Yield Prediction | - 97.5% Accuracy (Product Prediction)- 71.0% Accuracy (Retrosynthesis)- R² = 0.947 (Yield Prediction) | High performance when fine-tuned with limited data. |

| RS-Coreset [11] | Active representation learning using a coreset to approximate the full reaction space. | Yield Prediction | - >60% of predictions had absolute errors <10% on Buchwald-Hartwig dataset using only 5% of data for training. | Extremely high; state-of-the-art results with only 2.5% to 5% of data. |

| CARL [34] | Chemical Atom-Level Reaction Learning with Graph Neural Networks to model atom-level interactions. | Yield Prediction | Achieved state-of-the-art (SOTA) performance on multiple benchmark datasets. | Not explicitly quantified, but does not rely on large handcrafted feature sets. |

| Substrate Scope Contrastive Learning [35] | Contrastive pre-training on substrate scope tables to learn reactivity-aligned atomic representations. | Yield Prediction, Regioselectivity Prediction | Achieved comparable or better results than descriptor-based methods in yield prediction; successfully identified experimentally confirmed reactive sites. | Effective in low-data environments by repurposing existing published data. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

ReactionT5: A Foundation Model Approach

ReactionT5 is designed as a general-purpose, text-to-text transformer model for chemical reactions [33]. Its experimental protocol is structured in multiple distinct phases:

- Data Preparation and Tokenization: The model uses the Open Reaction Database (ORD) for pre-training. All compounds (reactants, reagents, catalysts, solvents, products) are encoded in the SMILES format. Special role tokens (e.g.,

REACTANT:,REAGENT:) are prepended to their respective SMILES sequences to delineate their function within the reaction. A SentencePiece unigram tokenizer, trained specifically on the compound library, is used to segment the input text into tokens. - Two-Stage Pre-Training:

- Compound Pre-training: The base T5 model is first pre-trained on a large library of single-molecule SMILES strings using a span-masked language modeling (span-MLM) objective. In this stage, contiguous spans of tokens within the SMILES string are masked, and the model is trained to predict them, learning fundamental molecular structure.

- Reaction Pre-training: The model from the first stage is then further pre-trained on the full ORD. The entire reaction is converted into a single text string incorporating the role-labeled SMILES sequences. The model is trained on the objectives of product prediction, retrosynthesis, and yield prediction simultaneously, allowing it to learn the complex relationships between compounds in a reaction context.

- Task-Specific Fine-Tuning: For downstream tasks like yield prediction, the pre-trained ReactionT5 model is fine-tuned on smaller, specific datasets. The input is the reaction conditions (reactants, reagents, etc.), and the output is the numerical yield value.

- Evaluation: Model performance is rigorously benchmarked on held-out test sets for product prediction (accuracy), retrosynthesis (top-1 accuracy), and yield prediction (coefficient of determination, R²).

The following workflow diagram illustrates the end-to-end process of the ReactionT5 model.

RS-Coreset: Data-Efficient Active Learning

The RS-Coreset methodology addresses the critical challenge of data scarcity by actively selecting the most informative experiments to run [11]. Its protocol is interactive and iterative:

- Reaction Space Definition: The full space of possible reaction combinations is defined, encompassing variables like catalysts, ligands, solvents, and additives.

- Initial Random Sampling: A small initial batch of reaction combinations is selected uniformly at random (or based on prior knowledge) and their yields are experimentally determined.

- Iterative Active Learning Loop: The core of the method involves repeated cycles of three steps:

- Representation Learning: A model updates the representation of the entire reaction space using the yield information from all experiments conducted so far.

- Data Selection (Coreset Construction): Using a maximum coverage algorithm, the model selects the next set of reaction combinations that are most "instructive"—typically those that are most diverse or most uncertain according to the current model.

- Yield Evaluation: The chemist performs experiments on the newly selected combinations and records the yields, which are added to the training data.

- Termination and Prediction: After a predetermined number of iterations or when model performance stabilizes, the loop terminates. The final model, trained on the smartly selected RS-Coreset, is used to predict yields for all remaining unexperimented combinations in the reaction space.

The diagram below visualizes this iterative, closed-loop process.

CARL: Atom-Level Interaction Modeling

The Chemical Atom-Level Reaction Learning (CARL) framework employs graph neural networks (GNNs) to explicitly model the fine-grained interactions that govern reaction outcomes [34].

- Graph Construction: The reactants and auxiliary molecules (catalysts, ligands, solvents, additives) are represented as molecular graphs, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges.

- Atom-Level Interaction Learning: The GNN processes these graphs to learn atom-level representations. A key differentiator of CARL is its explicit modeling of the interactions between atoms in the reactants and atoms in the auxiliary molecules. This allows the model to capture the mechanistic influence of conditions on the reaction, such as how a catalyst activates a specific bond.

- Yield Prediction: The learned interaction-rich representations are aggregated and passed through a feed-forward network to predict the final reaction yield.

- Interpretability: The framework can highlight key substructures in both reactants and auxiliary molecules that critically influence the reaction outcome, providing valuable chemical insights.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful application of these models often relies on specific chemical systems and computational tools. The table below details key reagents and materials referenced in the featured case studies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Case Studies

| Reagent / Material | Chemical Role | Function in Experiments | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palladium Catalysts [36] [11] | Catalyst | Facilitates key cross-coupling reactions (e.g., C-N, C-C bond formation) by enabling oxidative addition and reductive elimination steps. | Widely used in Buchwald-Hartwig and Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reactions for yield prediction. |

| Aryl Halides [35] | Substrate | A class of organic compounds serving as fundamental building blocks in many catalytic cycles; their structure variation tests model generalizability. | Used as the core substrate in the Substrate Scope Contrastive Learning study. |

| Ligands (e.g., Phosphines) [36] [11] | Catalyst Modulator | Binds to the metal catalyst (e.g., Pd) to tune its reactivity, stability, and selectivity, significantly impacting yield. | A critical variable in the reaction spaces explored by RS-Coreset and others. |

| Open Reaction Database (ORD) [33] | Data Resource | A large, open-access repository of chemical reaction data used for pre-training generalist ML models. | Served as the pre-training dataset for the ReactionT5 foundation model. |

| Buchwald-Hartwig / Suzuki Datasets [11] | Benchmark Data | Curated, high-throughput experimentation (HTE) datasets used for training and benchmarking yield prediction models. | Used to validate the performance of RS-Coreset and other models. |

The landscape of machine learning for reaction yield and selectivity prediction is diverse, offering solutions tailored to different research constraints. Foundation models like ReactionT5 demonstrate powerful, general-purpose capabilities, especially when fine-tuned, but require significant pre-training resources. In contrast, active learning approaches like RS-Coreset offer unparalleled data efficiency, making them ideal for exploring new reaction spaces with minimal experimental burden. Meanwhile, models like CARL and Substrate Scope Contrastive Learning provide deep chemical insights by focusing on atom-level interactions or leveraging human curation bias in existing data. The choice of model depends critically on the specific research context—including the volume of available data, the need for interpretability, and the computational resources at hand. These case studies collectively underscore that the most successful applications are those where the machine learning methodology is thoughtfully aligned with the fundamental chemistry of the problem.

Troubleshooting and Optimization: Enhancing Model Performance and Data Efficiency

Data scarcity remains a fundamental obstacle in applying machine learning (ML) to chemical reaction prediction and molecular property estimation, particularly within pharmaceutical research and development. Unlike data-rich domains where deep learning excels, experimental chemistry often produces limited, expensive-to-acquire data points, creating a significant mismatch with the data-hungry nature of conventional ML models. This challenge is especially pronounced in early-stage reaction development and molecular property prediction, where chemists traditionally operate by leveraging minimal data from a handful of relevant transformations or labeled molecular structures [26] [37].

The core of this problem lies in the vast, unexplored chemical space. With an estimated 10^60 drug-like molecules and innumerable possible reaction condition combinations, comprehensive data collection is fundamentally impossible [26]. This limitation is acutely felt in practical applications such as predicting sustainable aviation fuel properties or ADMET profiles in drug discovery, where labeled experimental data may be exceptionally scarce [37]. Consequently, reformulating ML problems to operate effectively in low-data regimes has become a critical research frontier, driving the development of specialized algorithms that can learn from limited examples while providing reliable, actionable predictions for chemists and drug development professionals.

Performance Comparison of Low-Data Regime Methodologies

Various ML strategies have been developed to address data scarcity, each with distinct operational principles and performance characteristics. The following table summarizes the quantitative performance of these key methodologies across different chemical prediction tasks.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Methods in Low-Data Regimes

| Methodology | Primary Mechanism | Application Context | Reported Performance | Data Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer Learning (Horizontal) [38] | Transfers knowledge from a source reaction to a different target reaction | Predicting reaction barriers for pericyclic reactions | MAE < 1 kcal mol⁻¹ (vs. >5 kcal mol⁻¹ pre-TL) [38] | Effective with as few as 33 new data points [38] |

| Transfer Learning (Diagonal) [38] | Transfers knowledge across both reaction type and theory level | Predicting reaction barriers at higher theory levels | MAE < 1 kcal mol⁻¹ [38] | Effective with as few as 39 new data points [38] |

| Deep Kernel Learning (DKL) [39] | Combins neural network feature learning with Gaussian process uncertainty | Buchwald-Hartwig cross-coupling yield prediction | Comparable performance to GNNs, with superior uncertainty quantification [39] | Effective in low-data scenarios due to reliable uncertainty estimates [39] |

| Adaptive Checkpointing with Specialization (ACS) [37] | Mitigates negative transfer in multi-task learning | Molecular property prediction (e.g., sustainable aviation fuels) | Consistently surpasses recent supervised methods in low-data benchmarks [37] | Accurate models with as few as 29 labeled samples [37] |

| Fine-Tuning (Transformer Models) [26] | Pre-training on large generic datasets, then fine-tuning on small, specific datasets | Stereospecific product prediction in carbohydrate chemistry | Top-1 accuracy of 70% (improvement of 27-40% over non-fine-tuned models) [26] | Effective with ~20,000 target reactions (vs. ~1,000,000 source reactions) [26] |

These methodologies demonstrate that strategic problem reformulation can drastically reduce data requirements. Transfer learning, in particular, achieves chemical accuracy (MAE < 1 kcal mol⁻¹) with orders of magnitude fewer data points than would be required to train a model from scratch [38]. Similarly, the ACS framework enables learning in the "ultra-low data regime" with fewer than 30 labeled examples, dramatically broadening the potential for AI-driven discovery in data-scarce domains [37].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Low-Data Methodologies

Transfer Learning for Reaction Barrier Prediction

Objective: To adapt a pre-trained Diels-Alder reaction barrier prediction model to make accurate predictions for other pericyclic reactions (horizontal TL) and at higher levels of theory (diagonal TL) using minimal new data [38].

Dataset Curation:

- Source Data: Density Functional Theory (DFT) free energy reaction barriers for Diels-Alder reactions, using semi-empirical quantum mechanical (SQM) inputs [40].

- Target Data: [3+2] cycloaddition reaction barriers (for hTL) and higher-level theory calculations (for dTL).

- Data Splits: Models evaluated in extremely low-data regimes, using as few as 33 data points for hTL and 39 for dTL for training [38].

Model Architecture & Training:

- Base Model: Neural networks pre-trained on Diels-Alder reaction barriers.

- Transfer Protocol:

- Horizontal TL: Re-train final layers of source model on small target dataset from different reaction class.

- Diagonal TL: Re-train final layers on small target dataset combining different reaction class and higher theory level.

- Evaluation Metric: Mean Absolute Error (MAE) against DFT-computed benchmarks, with chemical accuracy threshold of 1 kcal mol⁻¹ [38].

Deep Kernel Learning for Reaction Yield Prediction

Objective: To predict reaction yields with accurate uncertainty estimates using a hybrid architecture that combines neural networks with Gaussian processes in a low-data setting [39].

Dataset:

- Reaction System: Buchwald-Hartwig cross-coupling reactions from high-throughput experimentation [39].

- Size: 3,955 reactions with experimental yields [39].

- Representations: Multiple input representations tested including molecular descriptors, Morgan fingerprints, and Differential Reaction Fingerprints (DRFP) [39].

Model Implementation:

- Architecture:

- Feature Learning: Neural network (feed-forward or GNN) processes input representations to create embeddings.

- Prediction & Uncertainty: Gaussian process with base kernel uses embeddings to yield predictions with variance estimates.

- Training: All parameters optimized jointly by maximizing the log marginal likelihood of the GP [39].