Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Natural Products: Integrating Biocatalysis and Organic Chemistry for Drug Discovery

This article comprehensively reviews the burgeoning field of chemoenzymatic synthesis and its transformative impact on natural product research and drug development.

Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Natural Products: Integrating Biocatalysis and Organic Chemistry for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article comprehensively reviews the burgeoning field of chemoenzymatic synthesis and its transformative impact on natural product research and drug development. By integrating the exceptional selectivity of enzymatic transformations with the versatility of synthetic chemistry, chemoenzymatic strategies enable efficient access to complex molecular architectures that are challenging to produce by traditional means. We explore the foundational principles underpinning this interdisciplinary approach, showcase its application across diverse natural product classes including terpenoids, polyketides, and peptides, and provide practical guidance for troubleshooting and optimizing biocatalytic processes. Furthermore, we present comparative analyses validating the advantages of chemoenzymatic methods over purely chemical or biosynthetic approaches in terms of step-economy, sustainability, and the ability to generate structural analogues for structure-activity relationship studies. This review is tailored for researchers, synthetic chemists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage these powerful strategies in their work.

The Rise of Chemoenzymatic Synthesis: Principles and Evolutionary Milestones

Chemoenzymatic synthesis is an emerging paradigm in synthetic chemistry that strategically integrates enzymatic transformations with traditional organic synthesis in a multi-step approach to construct complex molecules [1]. Under this hybrid framework, practitioners harness the unparalleled regio- and stereoselectivity of biocatalytic methods while simultaneously leveraging the broad reaction diversity of contemporary synthetic chemistry [1]. This synergy is particularly valuable for streamlining access to bioactive natural products, which often contain intricate chiral centers and complex architectures that are challenging to produce using purely chemical or purely biological means [1].

The rationale for adopting chemoenzymatic strategies stems from recognizing the complementary strengths and limitations of both disciplines. While enzymes offer exquisite selectivity under mild, environmentally benign conditions, they typically catalyze only a small subset of organic transformations [1]. Conversely, synthetic organic chemistry provides powerful bond-forming capabilities but often requires harsh conditions and complex protection/deprotection strategies to achieve similar selectivity profiles [2]. By combining these approaches, chemoenzymatic synthesis enables more efficient synthetic routes with improved synthesis economy, often resulting in reduced step counts, higher overall yields, and superior stereocontrol compared to traditional methods [1].

Core Principles and Strategic Advantages

The theoretical foundation of chemoenzymatic synthesis rests on the strategic placement of enzymatic and chemical steps within a synthetic sequence to maximize their synergistic potential. This involves careful retrosynthetic analysis to identify bond disconnections where enzymatic transformations offer distinct advantages, particularly for forging stereocenters or functionalizing unbiased positions in complex molecular frameworks [3].

Key Strategic Advantages:

Unparalleled Selectivity: Enzymes provide exquisite stereospecificity and regioselectivity that can be difficult to achieve with chemical catalysts, especially for transformations occurring at unactivated carbon centers or within densely functionalized molecules [1]. For instance, P450 monooxygenases can perform site-selective oxidizations of aliphatic C-H bonds, enabling subsequent skeletal editing through Baeyer-Villiger rearrangements [4].

Reaction Diversity: The chemical synthesis component provides access to a vast array of non-natural reactions that expand the structural space beyond what is accessible through biosynthesis alone [5]. This includes transformations like oxidative enolate coupling, reductive amination, and various cyclization methods that complement enzymatic capabilities [1].

Streamlined Synthesis: The hybrid approach often significantly shortens synthetic routes to complex natural products. In multiple documented cases, chemoenzymatic strategies have reduced synthetic steps by 30-50% compared to traditional synthetic approaches while maintaining or improving overall yields [1].

Sustainability Profile: Enzymatic transformations typically occur under milder conditions with reduced environmental impact, aligning with green chemistry principles [5]. This includes operating in aqueous solutions at ambient temperature and pressure, reducing energy consumption and hazardous waste generation.

Representative Case Studies in Natural Product Synthesis

Recent literature demonstrates the transformative impact of chemoenzymatic approaches in natural product synthesis. The following case studies highlight different strategic applications, with key metrics summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Metrics from Recent Chemoenzymatic Natural Product Syntheses

| Natural Product | Key Enzymatic Transformation | Traditional Steps | Chemoenzymatic Steps | Yield Improvement | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jorunnamycin A | Dual Pictet-Spengler cyclization (SfmC) | 15+ steps (prior art) | Significantly reduced [1] | 18% from tyrosine [1] | One-step formation of pentacyclic core |

| Podophyllotoxin | Oxidative cyclization (2-ODD-PH) | 6-8 steps | 58-95% yield in key step [1] | 95% yield in biotransformation [1] | Superior stereocontrol |

| Kainic Acid | Oxidative cyclization (DsKabC) | 6+ steps | 2 steps [1] | 57% yield on gram-scale [1] | Gram-scale feasibility |

| Sorbicillinoids | Oxidative dearomatization (Monooxygenase) | Required stoichiometric chiral reagents | Eliminated chiral reagents [1] | Dramatic improvement in synthesis economy [1] | No stoichiometric chiral reagents |

| Terpene Scaffolds | Head-to-tail cyclization (SHCs) | Multi-step scaffold preparation | Single enzymatic step [3] | >99% ee and de [3] | Decagram scale production |

Tetrahydroisoquinoline Alkaloids: Jorunnamycin A and Saframycin A

The tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) alkaloids, including jorunnamycin A and saframycin A, represent a family of tyrosine-derived natural products with potent antitumor activity [1]. A recent chemoenzymatic synthesis utilized a phosphopantetheinylated SfmC, a dual Pictet-Spenglerase, to construct the common pentacyclic core from a tyrosine analog and corresponding aldehydes in a single enzymatic step [1]. Remarkably, this transformation accomplished the formation of two C-C bonds, three C-N bonds, and reduction of a thioester simultaneously [1]. The secondary amine was subsequently methylated chemically using formaldehyde and 2-picoline borane, yielding jorunnamycin A and saframycin A in 18% and 13% overall yield from tyrosine, respectively [1]. This approach constitutes the shortest synthesis of these alkaloids reported to date, demonstrating how enzymatic transformations can dramatically simplify complex molecular assembly.

Aryltetralin Lignans: Podophyllotoxin

Podophyllotoxin, an aryltetralin lignan with potent tubulin depolymerizing activity, has inspired semi-synthetic derivatives used in cancer immunotherapy [1]. Recent chemoenzymatic approaches have leveraged an α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase (2-ODD-PH) that catalyzes a key oxidative cyclization in the biosynthetic pathway [1]. Two independent research groups developed complementary strategies: one employed a biocatalytic kinetic resolution of racemic hydroxyyatein with 2-ODD-PH, yielding the key intermediate in 39% yield with 95% enantiomeric excess on gram-scale [1]. The other utilized oxidative enolate coupling to synthesize enantiopure yatein, which was transformed to the natural product via biotransformation with 2-ODD-PH in 95% yield on gram-scale [1]. Both approaches provided significant improvements in overall yield and stereocontrol compared to previous synthetic strategies.

Neuropharmacological Agents: Kainic Acid

Kainic acid, a monocyclic compound isolated from marine algae, serves as an important neuropharmacological agent due to its agonism of kainate receptors [1]. Despite its seemingly simple structure, the presence of three contiguous stereocenters presents significant synthetic challenges [1]. A recent chemoenzymatic synthesis employed a homolog of the α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase DabC, called DsKabC, which catalyzes the oxidative cyclization of "prekainic acid" to kainic acid [1]. The synthesis commenced with a reductive amination between L-glutamic acid and 3-methylcrotonaldehyde to generate the substrate, which was then converted to kainic acid using purified DsKabC in 46% yield on 10 mg scale [1]. By using E. coli expressing DsKabC for direct conversion of crude "prekainic acid," the process was scaled to gram-scale with 57% yield [1]. This two-step sequence represents a dramatic improvement over previous synthetic approaches that required at least six steps.

Fungal Metabolites: Sorbicillinoids

The sorbicillinoids are a family of fungal natural products with promising antiviral activities and intriguing molecular architectures that arise from asymmetric oxidative dearomatization of highly substituted phenols [1]. Significant chemical advances have been made in achieving this transformation, but they typically require stoichiometric chiral hypervalent iodine reagents or chiral Cu(I) salts [1]. Independent research groups demonstrated that an FAD-dependent monooxygenase from sorbicillinol biosynthesis can catalyze highly regioselective oxidative dearomatization of various substituted phenols with exquisite enantioselectivity [1]. The resulting products serve as versatile intermediates for synthesizing diverse sorbicillinoids, including rezishanone C, sorbicatechol A, epoxysorbicillinol, and urea sorbicillinoid, through subsequent chemical transformations such as Diels-Alder cycloadditions and Weitz-Scheffer epoxidations [1]. This biocatalytic oxidation strategy eliminates the need for stoichiometric chiral reagents and dramatically improves synthesis economy.

Terpene Scaffolds via Engineered Cyclases

Terpene synthesis represents a state-of-the-art area where chemoenzymatic approaches have shown particular utility [3]. A recent breakthrough demonstrated the use of engineered squalene-hopene cyclases (SHCs) for the stereocontrolled head-to-tail cyclization of abundant unbiased linear terpenes [3]. By combining engineered SHCs with a practical reaction setup, researchers generated ten distinct chiral terpene scaffolds with exceptional enantiomeric excess (>99% ee) and diastereomeric excess (>99% de) at scales up to decagrams [3]. The enzymatic cyclization overcame limitations of traditional chemical cyclization methods, which often require alternative initiation motifs or strong nucleophiles as terminating groups [3]. The resulting chiral templates were subsequently transformed to valuable (mero)-terpenes using interdisciplinary synthetic methods, including a catalytic ring-contraction of enol-ethers facilitated by cooperative iodine/lipase catalysis [3].

Experimental Methodologies

This section provides detailed protocols for key chemoenzymatic transformations cited in this review, enabling researchers to implement these strategies in their own synthetic campaigns.

Experimental Workflow for Chemoenzymatic Synthesis

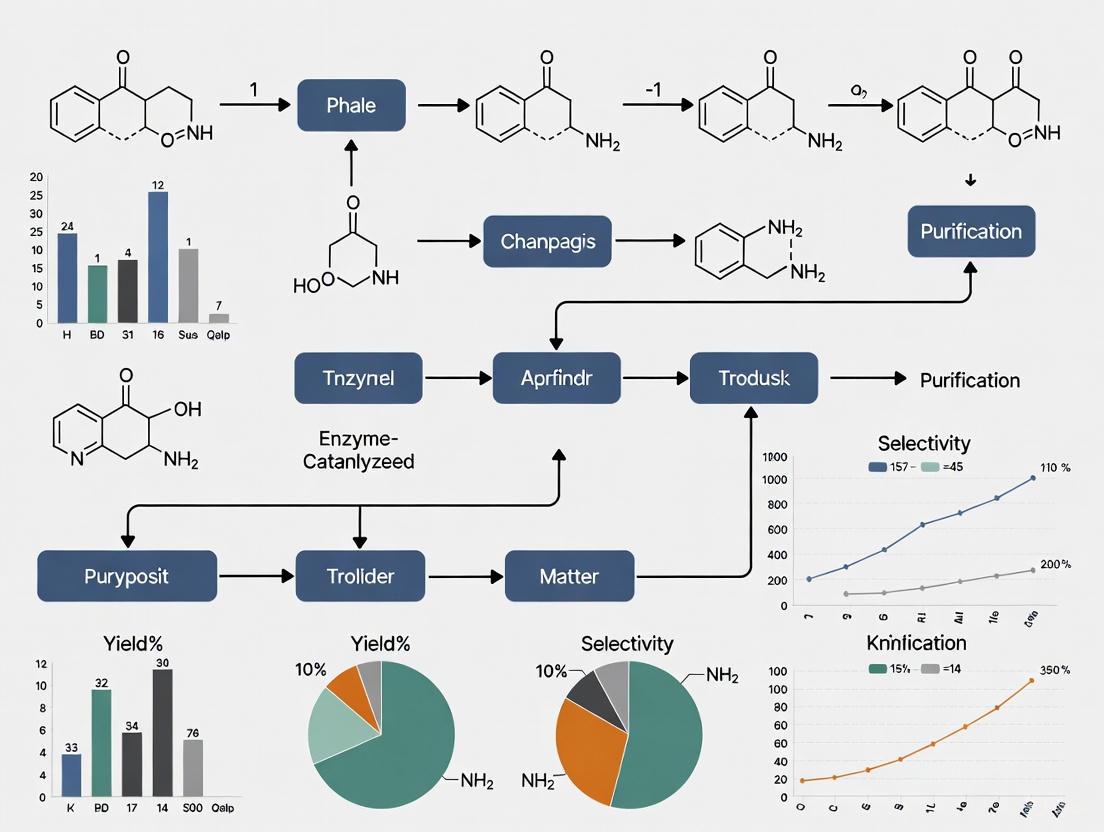

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for developing and executing a chemoenzymatic synthesis, integrating both chemical and enzymatic steps while minimizing transitions between reaction paradigms.

Biocatalytic Oxidative Dearomatization Protocol

This procedure details the enzymatic oxidative dearomatization of substituted phenols for sorbicillinoid synthesis, based on methodologies from Gulder and Narayan [1].

Reagents:

- FAD-dependent monooxygenase (cell-free extract or purified enzyme)

- Substrate phenol (e.g., compound 29 from [1])

- NADPH regenerating system (glucose-6-phosphate and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase)

- Coenzyme FAD (50 µM)

- Potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.4)

- Molecular oxygen (air-saturated buffer or gentle bubbling)

Procedure:

- Prepare the reaction mixture containing potassium phosphate buffer (10 mL), substrate phenol (0.5 mmol), FAD (50 µM), and glucose-6-phosphate (10 mM).

- Add glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (5 units) and the monooxygenase (10-50 mg protein depending on specific activity).

- Incubate the reaction at 30°C with gentle shaking (150 rpm) for 4-16 hours.

- Monitor reaction progress by TLC or HPLC until complete consumption of starting material.

- Extract the product with ethyl acetate (3 × 15 mL), combine organic layers, and dry over anhydrous sodium sulfate.

- Concentrate under reduced pressure and purify by flash chromatography (silica gel, hexanes/ethyl acetate gradient) to obtain the dearomatized product (e.g., compound 30).

Key Considerations:

- Maintain adequate aeration for optimal monooxygenase activity

- Enzyme specificity varies - screen multiple homologs for optimal results

- Scale can be increased proportionally with maintained aeration

Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Podophyllotoxin via 2-ODD-PH

This protocol describes the synthesis of podophyllotoxin using the α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase 2-ODD-PH, adapted from Fuchs and Renata [1].

Reagents:

- E. coli BL21(DE3) expressing 2-ODD-PH

- Substrate (enantiopure yatein or racemic hydroxyyatein)

- α-Ketoglutaric acid (10 mM final concentration)

- Ascorbic acid (2 mM final concentration)

- Ferrous ammonium sulfate (1 mM final concentration)

- HEPES buffer (50 mM, pH 7.5)

- Cerium(III) chloride (for benzylic oxidation)

- Sodium borohydride (for subsequent reduction)

Procedure:

- Grow E. coli expressing 2-ODD-PH in LB medium with appropriate antibiotics at 37°C to OD600 = 0.6-0.8.

- Induce expression with 0.1 mM IPTG and incubate at 18°C for 16-20 hours.

- Harvest cells by centrifugation (4,000 × g, 20 min) and resuspend in HEPES buffer.

- Prepare biotransformation mixture containing cell suspension (OD600 = 20), substrate (1 mM), α-ketoglutaric acid (10 mM), ascorbic acid (2 mM), and ferrous ammonium sulfate (1 mM).

- Incubate at 30°C with shaking (200 rpm) for 6-12 hours.

- Extract with ethyl acetate (3 × equal volume), dry organic layer over Na2SO4, and concentrate.

- For kinetic resolution approaches, recover both converted and unconverted enantiomers separately.

- For complete synthesis to podophyllotoxin: oxidize the enzymatic product with CrO3 in acetic acid, then reduce with NaBH4 in methanol to afford podophyllotoxin.

Key Considerations:

- Strict control of oxygenation improves reproducibility

- Substrate concentration should be optimized to prevent inhibition

- For gram-scale reactions, use fed-batch substrate addition

Squalene-Hopene Cyclase Catalyzed Terpene Cyclization

This protocol describes the cyclization of unbiased linear terpenes using engineered SHCs, based on the methodology described in [3].

Reagents:

- Engineered SHC variant (whole cells or cell-free extract)

- Linear terpene substrate (e.g., E,E-farnesol, geranyl geraniol)

- Triton X-100 (0.1% w/v)

- Cyclodextrin (optional, for substrate solubilization)

- Potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0)

- Magnesium chloride (5 mM)

Procedure:

- Prepare SHC-containing cells by growing the production strain in appropriate medium to late log phase.

- Harvest cells by centrifugation and resuspend in potassium phosphate buffer with magnesium chloride to OD600 = 30-50.

- Add Triton X-100 (0.1% w/v) to permeabilize cells.

- Add terpene substrate (1-10 mM) directly or pre-complexed with cyclodextrin for improved solubility.

- Incubate at 30°C with shaking (150 rpm) for 4-24 hours.

- Extract reaction mixture with pentane or hexanes (3 × equal volume).

- Combine organic layers, dry over Na2SO4, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Purify cyclized products by flash chromatography or distillation.

Key Considerations:

- Membrane-bound SHCs require detergent for optimal activity with hydrophobic substrates

- Engineered SHC variants show different selectivity profiles - screen for desired product

- Cyclodextrin complexation can improve conversion for poorly soluble substrates

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of chemoenzymatic synthesis requires access to specialized enzymatic and chemical reagents. Table 2 summarizes key research reagent solutions essential for the field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chemoenzymatic Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-C Bond Forming Enzymes | SfmC (Pictet-Spenglerase), Squalene-Hopene Cyclases, DabC homologs | Cyclization and carbon-carbon bond formation in complex scaffold synthesis | Often require co-expression with partner enzymes or phosphopantetheinyl transferases |

| C-X Bond Forming Enzymes | FAD-dependent Monooxygenases, α-Ketoglutarate-Dependent Dioxygenases, P450 Monooxygenases | Selective oxidation, hydroxylation, and heteroatom incorporation | Cofactor regeneration systems essential for practical implementation |

| Cofactor Regeneration Systems | NADPH, NADH, ATP | Drive thermodynamically unfavorable enzymatic reactions | In situ regeneration improves atom economy and cost-effectiveness |

| Enzyme Engineering Tools | Directed evolution kits, Site-saturation mutagenesis | Optimize enzyme activity, stability, and substrate scope | High-throughput screening essential for identifying improved variants |

| Specialized Substrates | Unbiased terpenes, Phenolic precursors, Amino acid derivatives | Serve as building blocks for enzymatic transformations | May require pre-complexation with cyclodextrins for solubility |

| Chiral Ligands & Catalysts | Hypervalent iodine reagents, Chiral Cu(I) complexes (for comparison) | Provide stereocontrol in chemical steps complementary to enzymatic steps | Enzymatic approaches often eliminate need for stoichiometric chiral reagents |

Computational Tools and Future Directions

The field of chemoenzymatic synthesis is increasingly benefiting from computational tools that facilitate route planning and optimization. Recently, Anand et al. developed minChemBio, a computational synthesis planning tool designed to identify synthetic routes that minimize transitions between biological and chemical reaction paradigms [6]. This approach addresses a significant challenge in chemoenzymatic synthesis: the costly and time-intensive purification steps often required when switching between chemical and biological reactions [6].

The minChemBio algorithm processes extensive reaction databases (1,808,938 chemical reactions from USPTO and 57,541 biological reactions from MetaNetX) to identify efficient pathways that minimize total transitions between reaction types [6]. The tool incorporates dGpredictor to assess thermodynamic favorability, ensuring proposed routes are energetically feasible [6]. In a demonstration, minChemBio identified a more efficient route to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid from glucose compared to previous approaches that required more expensive starting materials [6].

Future advancements in chemoenzymatic synthesis will likely focus on several key areas:

- Expanding Enzyme Toolkits: Continued discovery and engineering of enzymes for non-natural transformations will broaden the scope of accessible molecular architectures [4].

- Skeletal Editing Strategies: Approaches that enable precise modifications at the level of single atoms or bonds, such as the P450-controlled site-selective ring expansion recently reported, will provide powerful tools for fine-tuning molecular properties [4].

- Therapeutic Oligonucleotide Synthesis: Chemoenzymatic ligation methods are revolutionizing siRNA and sgRNA production, offering advantages in scalability, sustainability, and product quality compared to solid-phase synthesis [7].

- Integration with Synthetic Biology: Combining pathway engineering with targeted chemical modifications will enable production of increasingly complex natural product analogs [5].

Chemoenzymatic synthesis represents a powerful hybrid approach that strategically integrates the selective prowess of enzymatic catalysis with the synthetic flexibility of organic chemistry. As demonstrated by the case studies and methodologies presented herein, this paradigm offers significant advantages for accessing complex natural products and their analogs, including reduced step counts, improved stereocontrol, and enhanced sustainability profiles. The continued development of engineered enzymes, computational planning tools, and innovative synthetic strategies will further establish chemoenzymatic approaches as indispensable tools in natural product research and drug development. As the field advances, the seamless integration of biological and chemical transformations will undoubtedly unlock new possibilities for synthesizing complex molecular architectures with unprecedented efficiency and precision.

The field of organic synthesis has undergone a profound transformation over recent decades, increasingly moving from purely chemical methods toward integrated strategies that harness the power of biological catalysts. Chemoenzymatic synthesis, which strategically combines chemical transformations with enzymatic reactions, has emerged as a powerful paradigm for constructing complex molecules, particularly natural products with therapeutic potential. This approach has evolved from early applications in simple kinetic resolutions to sophisticated retrosynthetic planning that seamlessly integrates biocatalytic steps into synthetic blueprints. The historical development of this field reflects a growing recognition that enzymes offer unparalleled stereoselectivity, regioselectivity, and catalytic efficiency under environmentally benign conditions, often enabling synthetic routes that would be impractical or impossible through traditional chemical methods alone.

The driving force behind this paradigm shift stems from the escalating challenges in natural product synthesis and drug development. Natural products frequently possess complex molecular architectures with multiple stereocenters and sensitive functional groups, presenting significant synthetic hurdles. Furthermore, the pharmaceutical industry faces increasing pressure to develop more sustainable manufacturing processes. Chemoenzymatic strategies address both challenges simultaneously by providing synthetic shortcuts that reduce step counts while offering inherent atom economy and reduced environmental impact. This review examines key technological advances that have shaped modern chemoenzymatic approaches, from foundational kinetic resolution methods to contemporary computational planning tools, with a focus on their application in natural product synthesis for drug discovery.

Fundamental Techniques: Kinetic Resolutions and Beyond

The Principle of Kinetic Resolution

Kinetic resolution (KR) represents one of the earliest and most widely adopted applications of biocatalysis in organic synthesis. This technique exploits the inherent chiral discrimination of enzymes to differentiate between enantiomers in a racemic mixture, allowing one enantiomer to react preferentially while leaving the other essentially untouched. The theoretical foundation of kinetic resolution rests on the difference in reaction rates for the two enantiomers with an enantioselective catalyst, typically expressed through the selectivity factor (s), which represents the ratio of the rate constants for the two enantiomers.

Traditional kinetic resolution faced significant limitations, particularly the inherent 50% maximum yield of any single enantiomer from a racemic starting material. However, modern advances have largely overcome this constraint through dynamic kinetic resolutions (DKR) and related processes where the non-preferred enantiomer is continuously racemized under the reaction conditions, enabling theoretical yields of up to 100%. The strategic importance of kinetic resolution lies in its ability to provide enantioenriched intermediates that serve as building blocks for complex natural product synthesis, particularly for pharmaceuticals where chirality often dictates biological activity.

Advanced Kinetic Resolution in Sulfinyl Chemistry

Recent developments have expanded the scope of kinetic resolution to previously challenging chemical frameworks. A groundbreaking 2025 study demonstrated the first organocatalytic kinetic resolution of sulfinamides through N/O exchange, enabling access to enantioenriched sulfinyl scaffolds [8]. This transformation addresses a significant synthetic challenge, as enantiopure stereogenic-at-sulfur compounds have gained importance in pharmaceuticals due to their unique biological properties, yet their synthesis remained difficult.

The methodology employs squaramide catalysts to achieve high enantioselectivity through a proposed dual activation transition state, wherein both the sulfinamide and alcohol substrates engage with the catalyst via hydrogen-bonding interactions [8]. This system exhibits remarkable substrate generality, accommodating various alcohol types including alkyl, allylic, propargylic, and benzylic alcohols, with selectivity factors (s) reaching up to 143 in optimal cases. The practical utility of this method was demonstrated through the kinetic resolution sulfinylation of bioactive molecules, all affording corresponding products in excellent enantiomeric excess (typically >90% ee) [8].

Table 1: Key Developments in Chemoenzymatic Kinetic Resolution

| Development | Key Innovation | Selectivity/Scalability | Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organocatalytic KR of sulfinamides [8] | N/O exchange via hydrogen-bonding catalysis | Selectivity factor up to 143 | Broad alcohol scope, bioactive molecules |

| IRED-mediated KR for chiral amines [9] | Imine reductase catalysis | >99% ee, gram-scale | Cinacalcet analog synthesis |

| KRED optimization for ipatasertib synthesis [9] | Machine learning-aided enzyme engineering | 99.7% de (R,R-trans), 100 g/L substrate | API intermediate synthesis |

Contemporary Chemoenzymatic Strategies in Natural Product Synthesis

Skeletal Editing of Natural Product Scaffolds

A revolutionary approach that has emerged recently is the chemoenzymatic skeletal editing of natural product scaffolds, which enables precise modifications at the level of single atoms or bonds. A 2025 report detailed a methodology combining P450-controlled site-selective oxidation with subsequent Baeyer-Villiger rearrangement or ketone homologation to achieve ring expansion at aliphatic C─H sites [4]. This strategy represents a significant advancement in the ability to fine-tune molecular structures of complex natural products, potentially altering their biological activity for drug discovery applications.

The power of this approach lies in its synergistic combination of enzymatic and chemical steps. Engineered P450 catalysts provide the regioselectivity necessary to differentiate between similar C─H bonds in complex molecules, while subsequent chemical rearrlements introduce skeletal alterations. This methodology was applied to generate a panel of ring-expanded analogs of various complex natural products, with the skeletal modifications found to drastically alter anticancer activity in some compounds [4]. Such strategies provide medicinal chemists with powerful tools to rapidly access structurally diverse derivatives from natural product starting materials, accelerating structure-activity relationship studies.

Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Complex Terpenoids and Polyketides

The application of chemoenzymatic strategies to terpenoid and polyketide natural products has yielded particularly impressive results, as these classes often feature complex carbon skeletons with multiple stereocenters. Recent innovations include one-pot multienzyme (OPME) systems that mimic biosynthetic pathways while achieving synthetically useful yields and scales. For instance, the synthesis of nepetalactolone employed a ten-enzyme cascade that established three contiguous stereocenters from geraniol precursor with 93% yield [10]. This system exemplifies several advantages of chemoenzymatic approaches, including the ability to perform both oxidative and reductive transformations in the same pot using shared cofactor regeneration systems.

Similarly impressive, the Renata group has demonstrated gram-scale enzymatic hydroxylations of steroid cores with remarkable regioselectivity, oxidizing a single methylene group despite the presence of 6-7 other oxidizable sites [10]. These transformations achieve both high yields (67-83%) and excellent enantioselectivity, addressing a key challenge in chemical synthesis where such selective oxidations typically require complex protecting group strategies or suffer from poor selectivity.

Table 2: Representative Chemoenzymatic Syntheses of Natural Products

| Natural Product | Key Chemoenzymatic Step | Scale/Efficiency | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chrodrimanin C [10] | Enzymatic hydroxylation of 6,6,5 steroid core | Gram-scale, 67-83% yield | Single methylene oxidation despite 6-7 similar sites |

| Nepetalactolone [10] | 10-enzyme OPME cascade | 93% yield, ~1 g/L potential production | Sets 3 contiguous stereocenters, combined oxidative/reductive steps |

| Germacrene D [10] | Multi-enzyme triterpene synthesis | Milligram scale | Modular approach to natural and unnatural terpenoids |

| Scytalone [10] | Anthrole reductase-mediated ketone reduction | Small scale | Stereoselective reduction in naphthol system |

Novel Cyclization Strategies for Complex Peptide Architectures

Perhaps one of the most structurally challenging classes of natural products are the lariat lipopeptides, which feature complex macrocyclic architectures that have historically hampered efficient synthesis and diversification. A groundbreaking 2025 study reported a chemoenzymatic approach that repurposes non-ribosomal peptide cyclases for the synthesis of lariat-shaped macrocycles [11]. This methodology utilizes versatile penicillin-binding protein-type thioesterases (SurE and WolJ) and type-I thioesterases (TycC-TE) to cyclize unprotected, branched peptides bearing multiple nucleophiles in a site-selective manner [11].

The key innovation lies in engineering the substrate shape rather than the enzymes themselves. By incorporating an internal dipeptide unit as a "pseudo-N terminus" and strategically manipulating the stereochemical configuration of potential nucleophiles, the researchers successfully redirected the cyclization specificity of SurE from head-to-tail to head-to-side chain macrocyclization [11]. This approach demonstrates exceptional regiocontrol, with the pseudo-N-terminal residue serving exclusively as the nucleophile despite the presence of other potential nucleophiles in the branched substrate. The methodology was further extended through a tandem cyclization-acylation strategy that enabled one-pot, modular synthesis of lariat-shaped lipopeptides equipped with various acyl groups, with biological screening revealing derivatives with promising antimycobacterial activity (50% growth inhibition at 8-16 µg mL⁻¹) [11].

Retrosynthetic Planning and Computational Tools

The minChemBio Platform for Synthetic Planning

The increasing complexity of chemoenzymatic strategies has created a need for sophisticated computational tools that can facilitate retrosynthetic planning. Recently, researchers developed minChemBio, a computational synthesis planning tool specifically designed to optimize chemoenzymatic routes by minimizing transitions between chemical and biological reaction steps [6]. This addresses a critical practical challenge in chemoenzymatic synthesis, as separation and purification between different reaction types often account for significant time and cost investments.

The minChemBio platform was constructed by curating a massive dataset of 1,808,938 chemical reactions from the USPTO database and 57,541 biological reactions from the MetaNetX database [6]. After rigorous data processing to remove duplicates and incorrectly annotated reactions, the tool implements an algorithm that minimizes biological-to-chemical, chemical-to-biological, and chemical-to-chemical reaction transitions while maintaining synthetic feasibility. The platform incorporates dGpredictor, a tool to assess the thermodynamic favorability of proposed reactions, adding an important dimension to the planning process beyond mere step count minimization [6].

Practical Application and Limitations

The utility of minChemBio was demonstrated through the planning of a chemoenzymatic route to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid, a bioplastic precursor, from cheap and abundant glucose [6]. Notably, the tool identified routes using starting materials that were more economical than the product, addressing a common limitation of previous computational planning systems that often suggested syntheses requiring more expensive precursors than the target molecule itself. This practical consideration highlights the growing sophistication of retrosynthetic planning tools to incorporate economic factors alongside purely chemical considerations.

Despite these advances, current computational planning tools still face limitations. minChemBio does not currently label major and minor products in reactions, and its performance remains affected by misannotations and data upkeep issues in the underlying databases [6]. Nevertheless, such tools represent a significant step forward in enabling synthetic chemists to more efficiently leverage the growing toolbox of chemoenzymatic transformations for complex natural product synthesis.

Diagram 1: Organocatalytic Kinetic Resolution of Sulfinamides via N/O Exchange. This diagram illustrates the enantioselective pathway where squaramide catalysts enable kinetic resolution through dual activation transition states, yielding both enantioenriched sulfinate esters and recovered sulfinamides with high selectivity [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of chemoenzymatic strategies requires careful selection of specialized reagents and materials that enable the integration of enzymatic and chemical transformations. The following table summarizes key research reagent solutions essential for the experimental approaches discussed in this review.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chemoenzymatic Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engineered Glycosynthases | Chemoenzymatic glycoengineering of mAbs | Mutated ENGases (e.g., Asn/Asp to Ala) that prevent product hydrolysis | Endo-A E173Q/H, Endo-M mutants [12] |

| Squaramide Organocatalysts | Kinetic resolution via hydrogen-bonding catalysis | Dual activation of sulfinamides and alcohols through H-bonding | Catalyst E, F for sulfinamide KR [8] |

| P450 Monooxygenases | Site-selective C─H oxidation for skeletal editing | Engineered for divergent regioselectivity | P450-controlled ring expansion [4] |

| Non-ribosomal Peptide Cyclases | Macrocyclization of unprotected peptides | Broad substrate tolerance, stereospecificity | SurE, WolJ, TycC-TE [11] |

| One-Pot Multienzyme (OPME) Systems | Cascade biotransformations | Combined oxidative/reductive steps with cofactor regeneration | Nepetalactolone synthesis [10] |

| Ethylene Glycol (EG) Functionalized Substrates | Simplified enzymatic substrates for cyclization | Diol surrogate for pantetheine leaving group | SurE substrate for lariat peptide synthesis [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol: Organocatalytic Kinetic Resolution of Sulfinamides

This protocol describes the kinetic resolution of racemic N-Boc-sulfinamides through N/O exchange with alcohols, adapted from the 2025 Nature Communications report [8].

Materials:

- Racemic N-Boc-sulfinamide substrate (e.g., rac-1d, 0.1 mmol)

- Squaramide catalyst E or F (10 mol%)

- Anhydrous alcohol (1.0 mmol as nucleophile and solvent)

- Anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM)

- Molecular sieves (4 Å)

Procedure:

- Activate molecular sieves by flame-drying under vacuum.

- In an argon-filled glove box, combine sulfinamide substrate (0.1 mmol), squaramide catalyst (0.01 mmol), and 4 Å molecular sieves (50 mg) in a reaction vial.

- Add anhydrous alcohol (1.0 mmol) as both nucleophile and solvent.

- Seal the vial and stir the reaction at room temperature (23°C) for 48 hours.

- Monitor reaction progress by TLC or LC-MS until approximately 45-50% conversion is achieved.

- Concentrate the reaction mixture under reduced pressure.

- Purify by flash column chromatography (hexanes/ethyl acetate) to separate the sulfinate ester product and recovered sulfinamide.

- Determine enantiomeric excess by chiral HPLC or SFC analysis.

Notes:

- The optimal conversion for maximum enantiopurity is substrate-dependent but typically ranges from 40-50%.

- Catalyst E typically affords (S)-sulfinate esters and (R)-sulfinamides, while catalyst F provides the opposite enantiomers.

- The method demonstrates broad scope with linear, allylic, propargylic, and benzylic alcohols.

Protocol: SurE-Catalyzed Lariat Peptide Cyclization

This protocol describes the enzymatic macrocyclization of branched, EG-functionalized peptide substrates to form lariat-shaped lipopeptides, adapted from the 2025 Nature Chemistry report [11].

Materials:

- Branched peptide substrate with C-terminal EG ester (e.g., compound 4, 0.05 mmol)

- SurE macrocyclase (5 mol%)

- HEPES buffer (100 mM, pH 7.5)

- DMSO (for substrate solubilization)

Procedure:

- Express and purify SurE macrocyclase according to published procedures [11].

- Prepare the branched peptide substrate using standard Fmoc-SPPS with EG-functionalized resin and orthogonal Dde protection for lysine side chain modification.

- Prepare a stock solution of the peptide substrate in DMSO (10 mM concentration).

- In a reaction vial, combine HEPES buffer (100 mM, pH 7.5, 1 mL) with SurE enzyme (final concentration 5 mol% relative to substrate).

- Add the peptide substrate from DMSO stock (final concentration 0.5 mM, maintaining DMSO concentration ≤5% v/v).

- Incubate the reaction at 30°C with gentle shaking for 3 hours.

- Monitor reaction completion by LC-MS.

- Quench the reaction by adding an equal volume of acetonitrile.

- Purify the cyclic lariat peptide by preparative HPLC.

- Confirm cyclic structure by MS/MS analysis.

Notes:

- The pseudo-N-terminal nucleophile must be l-configured for efficient cyclization.

- SurE exhibits excellent regioselectivity when the native N-terminus is d-configured, exclusively forming the lariat cyclic product.

- The reaction typically proceeds quantitatively under optimized conditions.

Diagram 2: Computational Retrosynthetic Planning with minChemBio. This workflow illustrates how the minChemBio platform utilizes curated reaction databases and transition minimization algorithms to design efficient chemoenzymatic routes from simple starting materials to valuable target molecules [6].

The historical trajectory of chemoenzymatic synthesis reveals a field that has matured from specialized applications in kinetic resolution to a comprehensive synthetic paradigm capable of addressing some of the most complex challenges in natural product synthesis. The integration of enzymatic and chemical transformations has progressively blurred the traditional boundaries between biosynthesis and organic synthesis, giving rise to hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both disciplines. As the field advances, several emerging trends suggest future directions, including the increased use of artificial intelligence for enzyme engineering and pathway design, the development of more sophisticated one-pot multi-step cascades, and the application of chemoenzymatic strategies to novel therapeutic modalities beyond traditional small molecules.

The ongoing refinement of computational planning tools like minChemBio represents a crucial step toward mainstream adoption of chemoenzymatic approaches in both academic and industrial settings. As these tools incorporate more sophisticated considerations of enzyme compatibility, reaction conditions, and scalability, they will increasingly enable synthetic chemists to design efficient chemoenzymatic routes for complex natural products and pharmaceutical targets. Furthermore, the continued discovery and engineering of enzymes with novel catalytic activities promises to expand the synthetic toolbox available for retrosynthetic planning. Collectively, these advances solidify chemoenzymatic synthesis as an indispensable strategy in modern organic synthesis, particularly for the construction of structurally complex natural products with therapeutic potential.

The field of organic synthesis is increasingly moving beyond the question "Can we make it?" to focus on "How well can we make it?"—emphasizing efficiency, economy, and modularity [13]. Within this evolving landscape, chemoenzymatic synthesis has emerged as a powerful strategy that integrates the precision of biological catalysts with the flexibility of synthetic methodology. This approach leverages enzymes as potent, selective catalysts alongside traditional synthetic transformations to streamline the synthesis of complex natural products and pharmaceutical targets [13] [14]. The complementary nature of these disciplines enables synthetic chemists to overcome challenges that remain formidable when using either methodology alone.

Natural products have long served as inspiration for synthetic chemists, providing valuable blueprints for pharmaceutical development [13]. Similarly, the enzymes that constitute biosynthetic pathways to these molecules offer equally intriguing opportunities for synthetic applications [13]. Recent advances in genomics, bioinformatics, and molecular biology have provided chemists with unprecedented tools for biosynthetic analysis and enzyme engineering, creating new opportunities for enzyme applications in total synthesis [13]. As Nature's catalysts, enzymes demonstrate exceptional regio-, chemo-, and enantioselectivity across diverse substrates and reactions—many of which are difficult or impossible to replicate conventionally [13]. The integration of enzymatic and synthetic chemistry represents a frontier in synthetic methodology that combines sustainability with precision [14].

Fundamental Principles of Enzyme Catalysis

Enzymatic Selectivity and Transition State Stabilization

Enzymes achieve extraordinary rate accelerations through strong stabilizing interactions between the protein and reaction transition states [15]. The defining property of enzymatic catalysts is their specificity for binding the transition state with significantly higher affinity than the substrate [15]. This fundamental principle enables enzymes to provide immense rate accelerations while maintaining precise control over reaction outcome. For example, orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase (OMPDC) demonstrates a remarkable 31 kcal/mol stabilization of the transition state compared to only 8 kcal/mol stabilization of the ground-state complex [15].

The architectural features that enable this specificity provide key insights for harnessing enzymatic power in synthesis. Many enzymes exist in flexible, entropically rich ground states that convert to stiff, catalytically active Michaelis complexes upon substrate binding [15]. This conformational transition reduces the substrate-binding energy expressed at the Michaelis complex while enabling full expression of large transition-state binding energies [15]. The utilization of substrate-binding energy to drive these conformational changes represents a sophisticated evolutionary adaptation that enables both specificity and catalytic power.

Structural Dynamics in Enzyme Function

The coexistence of protein flexibility and stiffness represents complementary properties essential for extraordinary catalytic efficiency [15]. While catalytic events occur at stiff protein active sites, enzymes frequently evolve with flexible structures in their unliganded forms that undergo large ligand-driven conformational changes to active, stiff forms [15]. This paradigm reconciles the historic "lock-and-key" and "induced-fit" models of enzyme catalysis [15].

Experimental evidence indicates that phosphodianion-binding energy of phosphate monoester substrates drives conversion of their protein catalysts from flexible ground states to stiff, catalytically active Michaelis complexes [15]. This mechanism extends to multiple enzyme systems, including triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) and glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH) [15]. The existence of flexible ground states provides a mechanism for utilizing ligand-binding energy to mold catalysts into active forms, reducing expressed substrate-binding energy while enabling full expression of large transition-state binding energies [15].

Table 1: Key Enzymes in Chemoenzymatic Synthesis and Their Functions

| Enzyme | Reaction Catalyzed | Selectivity Features | Applications in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transaminases | Chiral amine synthesis | Enantioselective | Sitagliptin intermediate [14] |

| Lipases | Kinetic resolution | Enantioselective | Tetrazomine synthesis [13] |

| Purine Nucleoside Phosphorylases | Glycosidic bond formation | Regio- and stereoselective | Islatravir synthesis [14] |

| Triosephosphate Isomerase (TIM) | Proton transfer | Dianion activation | Fundamental studies [15] |

| OMP Decarboxylase | Decarboxylation | Transition state stabilization | Fundamental studies [15] |

Strategic Frameworks for Chemoenzymatic Synthesis

Classification of Chemoenzymatic Approaches

The integration of biocatalysis with chemical synthesis follows several conceptual frameworks, which can be categorized into four primary approaches based on the role of enzymes in the synthetic design [13]:

- Providing enantioenriched starting materials or intermediates: Enzymes play a supporting role, typically performing kinetic resolutions or desymmetrizations to generate chiral compounds without influencing the broader synthetic design.

- Enabling evaluation of biosynthetic hypotheses: Chemically or chemoenzymatically synthesized intermediates probe subsequent biosynthetic transformations, facilitating characterization of putative or poorly-understood enzymes.

- Motivating retrosynthetic disconnections with known enzymatic reactions: Enzymatic reactions serve as inspiration for synthetic designs, influencing the broader retrosynthetic strategy through deliberate incorporation of enzymatic transformations.

- Motivating retrosynthetic disconnections by filling methodological gaps: Retrosynthetic disconnections are proposed prior to identifying suitable enzymes, leveraging enzyme discovery and engineering to perform roles inaccessible to chemical methodology.

These approaches represent a spectrum of integration depth, from using enzymes as practical tools to resolution to fully embedding biocatalytic logic into retrosynthetic planning.

Approach 1: Providing Enantioenriched Intermediates

In this approach, enzymes perform supporting roles in multi-step syntheses, typically through kinetic resolution to generate chiral compounds. The synthetic logic remains largely unchanged, with the enzyme providing access to enantiopure materials from racemic precursors. A representative example comes from the synthesis of tetrazomine, which features an unusual 3-hydroxypipecolic acid motif [13]. The Williams group implemented a chemoenzymatic synthesis of chiral pipecolic acid derivative starting from picolinic acid [13]. Exhaustive hydrogenation furnished racemic cis-3-hydroxypipecolic acid, which was protected and esterified before treatment with lipase PS and vinyl acetate in diisopropyl ether achieved kinetic resolution to provide nearly quantitative yield (46%) of the enantiopure material [13]. Despite its seemingly trivial role, the biocatalytic resolution proved instrumental in assigning the correct configuration of the natural product [13].

This approach leverages the inherent chiral environment of enzyme active sites, which typically favor one enantiomer over the other, leading to preferential consumption of the "matched" isomer [13]. While kinetic resolution theoretically limits yields to 50%, this drawback is mitigated by the availability and lower cost of racemic materials compared to chiral alternatives [13]. Furthermore, enzymes can also catalyze desymmetrization of meso compounds, bypassing the 50% yield limitation [13].

Approach 3: Enzymatic Reactions Driving Retrosynthetic Design

In contrast to the supporting role described in Approach 1, enzymatic reactions can serve as central inspiration for synthetic designs. As the biocatalytic toolbox expands, more syntheses incorporate enzymatic disconnections as simplifying transforms that influence the broader synthetic strategy [13]. This represents a deeper integration of biocatalysis into synthetic planning, resulting in retrosynthetic analyses orthogonal to those relying solely on chemical transformations.

Industrial applications demonstrate the power of this approach. In the synthesis of islatravir, purine nucleoside phosphorylase and phosphopentomutase were evolved to catalyze the regio- and stereoselective installation of an unnatural purine moiety on chemically or enzymatically synthesized unprotected, unnatural deoxyribose analogs [14]. This enzymatic transformation enabled a more efficient overall process than possible with purely synthetic methodology [14]. Similarly, the evolution and implementation of a transaminase to selectively catalyze formation of the chiral amine in sitagliptin from chemically derived pro-sitagliptin represents a landmark achievement in this approach [14].

Computational Framework for Hybrid Synthesis Planning

Integrated Retrosynthetic Search Algorithm

The identification of synthetic routes combining enzymatic and synthetic steps has traditionally been a manual, intuition-driven process [14]. Recent advances in computer-aided synthesis planning (CASP) have enabled the development of algorithms that balance exploration of enzymatic and synthetic transformations to identify hybrid synthesis plans [14]. This approach extends the space of retrosynthetic moves by thousands of uniquely enzymatic one-step transformations, discovering routes to molecules for which purely synthetic or enzymatic searches find none [14].

The hybrid search algorithm employs two neural network models for retrosynthesis—one covering 7,984 enzymatic transformations and another covering 163,723 synthetic transformations [14]. This integrated approach prioritizes possible retrosynthetic steps in a way that balances exploration of both enzymatic and synthetic steps, identifying shorter pathways where enzymatic steps replace multiple synthetic steps [14]. Application to pharmaceutical targets such as (-)-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC, dronabinol) and R,R-formoterol (arformoterol) demonstrates how this strategy facilitates replacement of metal catalysis, high step counts, or costly enantiomeric resolution with more efficient hybrid proposals [14].

Table 2: Comparison of Enzymatic and Synthetic Reaction Databases for CASP

| Database Feature | Enzymatic Database (BKMS) | Synthetic Database (Reaxys) |

|---|---|---|

| Total Reactions | ~37,000 | >10,000,000 |

| Unique Templates | 7,984 | 163,723 |

| Data Sources | BRENDA, KEGG, Metacyc, SABIO-RK | Reaxys |

| Template Precedent | ~80% of templates have only one precedent | Templates typically have multiple precedents |

| Transformation Coverage | Highly specific, biologically relevant | Broad, diverse chemical space |

Unique Value of Enzymatic Transformations

Analysis of enzymatic and synthetic reaction databases reveals that enzymatic transformations expand accessible chemical space beyond synthetic methodology alone [14]. Although the synthetic organic chemistry toolkit encompasses far more transformations than known enzymatic chemistry, enzymes catalyze numerous unique reactions not captured by synthetic reaction templates [14]. The hybrid search algorithm identifies 4,169 unique enzymatic templates beyond those captured by synthetic chemistry, demonstrating the value of integrating both approaches [14].

The template-based approach maintains a link between retrosynthetic suggestions and precedent reactions from the database, making model suggestions interpretable and actionable as starting points for enzyme selection and optimization [14]. This connection to experimental precedent is crucial for practical implementation of proposed synthetic routes.

Diagram 1: Hybrid retrosynthetic search algorithm integrating enzymatic and synthetic transformation models. The algorithm balances exploration of both enzymatic (green) and synthetic (blue) steps to identify viable hybrid synthesis routes.

Experimental Implementation and Optimization

Chemoenzymatic Reaction Optimization

Successful implementation of chemoenzymatic synthesis requires optimization of reaction conditions to maximize efficiency and cost-effectiveness. A representative example comes from the chemoenzymatic synthesis of milk thistle flavonolignan glucuronides, where systematic optimization enhanced yield while reducing resource requirements [16]. This process evaluated multiple parameters including enzyme source, enzyme concentration, and cofactor concentration relative to substrate [16].

Optimized conditions used at least one-fourth the amount of microsomal protein and UDP-glucuronic acid (UDPGA) cofactor compared to typical conditions employing human-derived subcellular fractions, providing substantial cost savings [16]. The optimization protocol examined enzyme source (bovine liver microsomes versus S9 fraction), enzyme concentration (1, 0.5, and 0.25 mg/ml for bovine liver microsomes), and UDPGA concentration relative to flavonolignan concentration (10-fold and 2-fold molar excess) [16]. This systematic approach enabled large-scale synthesis (40 mg starting material) that generated multiple glucuronide metabolites in quantities sufficient for characterization and biological testing [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chemoenzymatic Synthesis

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Bovine Liver Microsomes (BLMs) | Cost-effective enzyme source for glucuronidation | Milk thistle flavonolignan glucuronidation [16] |

| UDP-Glucuronic Acid (UDPGA) | Cofactor for glucuronosyltransferases | Flavonolignan glucuronidation [16] |

| Lipase PS | Enantioselective kinetic resolution | Tetrazomine pipecolic acid resolution [13] |

| Alamethicin | Pore-forming peptide for membrane disruption | Activation of microsomal enzymes [16] |

| Transaminases | Chiral amine synthesis | Sitagliptin intermediate production [14] |

| Purine Nucleoside Phosphorylases | Glycosidic bond formation | Islatravir synthesis [14] |

Case Studies in Advanced Chemoenzymatic Synthesis

Pharmaceutical Target Synthesis

The synthesis of complex pharmaceutical targets exemplifies the power of chemoenzymatic approaches. The application of hybrid synthesis planning to (-)-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC, dronabinol) and R,R-formoterol (arformoterol) demonstrates how enzymatic steps can replace metal catalysis, reduce step counts, or eliminate costly enantiomeric resolution [14]. In these cases, the integrated computational approach identified hybrid routes that would have remained undiscovered using only synthetic or enzymatic reactions in isolation [14].

Another compelling example comes from the synthesis of islatravir, where enzymatic transformations provided superior regioselectivity compared to synthetic methods [14]. The implementation of evolved purine nucleoside phosphorylase and phosphopentomutase enzymes catalyzed regio- and stereoselective installation of an unnatural purine moiety on unprotected, unnatural deoxyribose analogs [14]. This biocatalytic strategy enabled a more efficient process overall than possible with purely synthetic methodology [14].

Natural Product Synthesis

The synthesis of tetrazomine illustrates the strategic application of enzymatic resolution to access challenging stereocenters [13]. The target molecule features an unusual 3-hydroxypipecolic acid motif with initially unassigned stereochemistry [13]. The chemoenzymatic approach provided enantiopure material for structure confirmation while delivering key intermediates for the total synthesis. The Williams group employed lipase PS-mediated kinetic resolution of racemic cis-3-hydroxypipecolic acid derivative, achieving nearly quantitative yield (46%) of enantiopure material that was advanced to the final natural product [13].

Diagram 2: Chemoenzymatic synthesis of tetrazomine pipecolic acid fragment. The enzymatic resolution with Lipase PS provides the key enantiopure intermediate from racemic starting material.

The continued advancement of chemoenzymatic synthesis depends on addressing several challenges and opportunities. Current synthetic enzyme design remains limited by incomplete knowledge of enzymatic machinery, suggesting that advances in natural enzyme characterization will unlock new design strategies [17]. Computational techniques that access relevant time and length scales for enzyme activity represent a key research area within the catalysis community [17]. Particularly promising is the development of ensemble-based approaches to synthetic enzyme design that move beyond the outdated "single structure" picture to account for structural dynamics and dynamic allostery [17].

The integration of enzymatic and synthetic chemistry represents more than a methodological convenience—it embodies a strategic approach to synthesis that leverages the unique strengths of both disciplines. Enzymes provide unparalleled selectivity and sustainable reaction conditions, while synthetic methodology offers breadth of transformation and operational simplicity. The future of chemoenzymatic synthesis will be shaped by advances in several areas: (1) continued expansion of the enzymatic reaction toolkit through discovery and engineering; (2) development of more sophisticated computational tools for hybrid pathway design; and (3) improved understanding of enzyme dynamics and allostery to inform design strategies [17] [14]. As these advances mature, the seamless integration of enzymatic and synthetic steps will increasingly become standard practice in complex molecule synthesis.

The combination of state-of-the-art chemical and biocatalytic methodology positions practitioners of chemoenzymatic synthesis to implement advances in both fields toward concise synthesis of complex natural products and pharmaceutical targets [13]. By leveraging the unique potential of biocatalytic transformations to streamline synthetic sequences, this hybrid approach represents a powerful strategy for addressing the evolving challenges of synthetic efficiency, economy, and modularity [13]. As the field progresses, the continued integration of enzymatic selectivity with synthetic flexibility will undoubtedly yield new innovations in complex molecule synthesis.

Four Conceptual Frameworks for Enzyme Integration in Multi-step Synthesis

The field of organic synthesis is increasingly focused on efficiency, economy, and modularity, moving beyond the fundamental question of whether a molecule can be made to how well it can be made [13]. Within this context, chemoenzymatic synthesis—the integration of enzymatic and chemical synthetic steps—has emerged as a powerful strategy for the concise synthesis of complex natural products. Enzymes, as Nature's catalysts, offer unparalleled regio-, chemo-, and enantioselectivity across a wide range of transformations, many of which are challenging to replicate with traditional synthetic chemistry alone [13]. Recent breakthroughs in genomics, bioinformatics, and molecular biology, particularly directed evolution, have provided synthetic chemists with an unprecedented ability to utilize and tailor enzymes for synthetic campaigns [13] [5].

This whitepaper outlines four primary conceptual frameworks for integrating biocatalysis into multi-step synthesis, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a structured guide for strategic planning. These frameworks are not mutually exclusive but represent distinct philosophical approaches to leveraging the unique capabilities of enzymes within a synthetic sequence.

The Four Conceptual Frameworks

The integration of enzymes into synthetic design can be categorized into four main approaches, distinguished by the role of the enzyme and its influence on the overarching retrosynthetic logic.

Approach 1: To Provide Enantioenriched Starting Materials or Intermediates

In this approach, enzymes play a supporting role, typically performing kinetic resolutions or desymmetrizations to generate chiral, enantioenriched compounds from racemic or achiral precursors [13]. The critical distinction of this approach is that the enzymatic step does not influence the broader synthetic design; the overall logic of the route remains unchanged, with the enzyme serving as a highly selective tool to set stereochemistry.

Mechanism: Enzymes are ideal for kinetic resolution due to the chiral environment of their active sites, which favors binding and transformation of one enantiomer over the other. Lipases and acylases have been widely used for this purpose [13]. While kinetic resolution has a maximum theoretical yield of 50%, desymmetrization of meso compounds can overcome this limitation.

Experimental Protocol: Kinetic Resolution of a Pipecolic Acid Derivative

- Objective: Obtain enantiopure Fmoc-protected 3-hydroxypipecolic acid ester, a key intermediate in the synthesis of tetrazomine [13].

- Materials: Racemic Fmoc-3-hydroxypipecolic acid ester, Lipase PS (from Burkholderia cepacia), vinyl acetate, diisopropyl ether.

- Procedure:

- Dissolve the racemic substrate (e.g., compound 17 from the synthesis) in dry diisopropyl ether.

- Add lipase PS and vinyl acetate.

- Stir the reaction mixture at room temperature for 3.5 days.

- Monitor reaction progress by TLC or chiral HPLC.

- Upon completion, filter the mixture to remove the enzyme.

- Concentrate the filtrate under reduced pressure.

- Purify the product (e.g., enantiopure acetate 18) using flash chromatography.

- Key Parameters: The choice of solvent and acyl donor (e.g., vinyl acetate) is crucial for high enzyme activity and conversion. The reaction time must be optimized to achieve high enantiomeric excess (e.g., 98:2 er reported) [13].

Approach 2: To Enable the Evaluation of Biosynthetic Hypotheses

This approach employs chemical or chemoenzymatic synthesis to access biosynthetic intermediates, which are then used to probe the function of putative biosynthetic enzymes in vitro. This provides a direct, chemical-biology-based alternative to genetic knockout experiments for elucidating biosynthetic pathways [13].

Mechanism: Putative biosynthetic intermediates are synthesized and incubated with purified enzymes or enzyme cocktails. The products are then analyzed to confirm the enzymatic activity and characterize the transformation, thereby validating or refuting a biosynthetic hypothesis.

Experimental Protocol: In Vitro Reconstitution of a Biosynthetic Pathway

- Objective: Characterize the function of a putative cytochrome P450 enzyme in a biosynthetic pathway.

- Materials: Chemically synthesized putative substrate, purified P450 enzyme, NADPH cytochrome P450 reductase, NADPH cofactor, reaction buffer.

- Procedure:

- Prepare a reaction buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5).

- Add the synthesized substrate to the buffer, ensuring good solubility (may require a co-solvent like DMSO, kept at low concentration).

- Add the purified P450 enzyme and its cognate reductase.

- Initiate the reaction by adding NADPH.

- Incubate at a defined temperature (e.g., 30°C) with shaking.

- Quench the reaction at various time points by adding an organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile).

- Analyze the quenched samples using LC-MS to detect product formation.

- Isolate and characterize the product(s) using NMR spectroscopy to determine structure.

- Key Parameters: The stoichiometry between the P450 and its reductase is critical for optimal activity [18]. Control reactions without the enzyme or without NADPH are essential.

Approach 3: To Motivate Retrosynthetic Disconnections with Known Enzymatic Reactions

Here, known enzymatic reactions serve as direct inspiration for synthetic design. The deliberate incorporation of a specific enzymatic transformation acts as a simplifying "T-goal" in retrosynthetic analysis, fundamentally shaping the route in a way that is orthogonal to purely chemical logic [13].

Mechanism: This strategy leverages the unique selectivity of enzymes to make strategic bond disconnections that would be non-trivial with synthetic chemistry. Examples include using terpene cyclases to construct complex carbocyclic cores in one step [18] or P450 enzymes for site-selective C–H oxidation [4].

Experimental Protocol: Chemoenzymatic Skeletal Editing via Ring Expansion

- Objective: Perform site-selective ring expansion of a natural product scaffold via a chemoenzymatic cascade [4].

- Materials: Natural product substrate, engineered P450 enzyme (whole cells or purified enzyme), NADPH regeneration system, m-CPBA or diazomethane for subsequent chemical steps.

- Procedure:

- P450-Mediated Oxidation: Incubate the substrate with an engineered P450 catalyst to achieve site-selective oxidation of an aliphatic C–H bond to a ketone.

- Workup: Extract the ketone intermediate.

- Skeletal Editing:

- Path A (Baeyer-Villiger): Treat the ketone with m-CPBA to insert an oxygen atom, forming a ring-expanded lactone.

- Path B (Homologation): React the ketone with diazomethane to form a homologated, ring-expanded product.

- Purification: Isolate the final skeletally edited analog using preparative HPLC.

- Key Parameters: The selectivity of the ring expansion is dictated by the initial, enzyme-controlled site of oxidation. Engineering the P450 is often necessary to achieve divergent regioselectivity on complex scaffolds [4].

Approach 4: To Motivate Retrosynthetic Disconnections by Filling Gaps in Current Methodology

This forward-looking approach involves proposing a retrosynthetic disconnection for which no suitable catalyst currently exists. Advances in genetic technology and directed evolution are then harnessed to discover or engineer an enzyme to perform this "gap-filling" role, which may be traditionally occupied by or entirely inaccessible to chemical methodology [13].

Mechanism: The initial disconnection is chosen based on synthetic logic, potentially without a specific biocatalyst in mind. Researchers then screen metagenomic libraries or employ directed evolution campaigns to create "new-to-nature" biocatalysts that can achieve the desired transformation with high selectivity.

Experimental Protocol: Directed Evolution of a "New-to-Nature" Biocatalyst

- Objective: Engineer an enzyme to catalyze a non-natural reaction essential to a proposed synthetic route.

- Materials: Gene library of the parent enzyme, expression host (e.g., E. coli), chemical substrate for the desired reaction, high-throughput screening assay.

- Procedure:

- Gene Library Construction: Introduce random mutations into the gene of the parent enzyme using error-prone PCR or other gene diversification methods.

- Expression and Screening: Express the mutant library in a microbial host. Culture clones in microtiter plates and lyse cells to release enzymes.

- Activity Screening: Add the target substrate to each well and use a high-throughput assay (e.g., colorimetric, fluorescence, or mass spectrometry-based) to identify active clones.

- Hit Validation: Sequence positive hits and characterize the improved enzymes.

- Iterative Evolution: Use the best hit from one round as the template for the next round of evolution, potentially focusing on different regions of the enzyme, until the desired activity and selectivity are achieved.

- Key Parameters: The design of a rapid and reliable screening assay is the most critical factor for success. The substrate scope and stability of the evolved enzyme must be characterized before integration into a multi-step synthesis.

Quantitative Comparison of the Frameworks

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and challenges associated with each framework.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of the Four Frameworks for Enzyme Integration

| Framework | Influence on Synthetic Design | Key Enzyme Function | Technical Complexity | Relative Step Count Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Provide Enantioenriched Intermediates | Minimal (Supporting role) | Kinetic resolution, desymmetrization | Low | Neutral |

| 2. Evaluate Biosynthetic Hypotheses | Retrospective (Hypothesis-driven) | Pathway validation, intermediate transformation | Medium | Variable |

| 3. Motivate Disconnections with Known Enzymes | High (Directs T-goal) | Core bond formation, selective functionalization | Medium to High | Reductive |

| 4. Motivate Disconnections by Filling Gaps | Transformative (Creates new methodology) | "New-to-nature" catalysis | Very High | Potentially Highly Reductive |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of these frameworks relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chemoenzymatic Synthesis

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Lipases & Esterases (e.g., Lipase PS) | Kinetic resolution of racemic alcohols/acids via enantioselective hydrolysis or acylation. | Synthesis of enantiopure pipecolic acid derivatives [13]. |

| Engineered P450 Monooxygenases | Site- and stereoselective oxidation of unactivated C-H bonds. | Skeletal editing via late-stage ring expansion [4]. |

| Terpene Cyclases (e.g., Pentalenene Synthase) | One-step enzymatic cyclization of linear precursors to complex polycyclic cores. | Construction of the guaia-6,10(14)-diene scaffold in englerin A synthesis [18]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Nanocarriers for enzyme co-immobilization, enhancing stability and enabling cascade reactions. | Compartmentalization of multi-enzyme systems to minimize diffusion limitations [19]. |

| Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Nanoflowers (HNFs) | Self-assembled immobilization matrices that boost enzymatic activity and stability. | Co-immobilization of cellulases for cellulose-to-glucose conversion [20]. |

| Directed Evolution Kits | Platforms for gene mutagenesis and high-throughput screening to engineer enzyme function. | Creating bespoke biocatalysts for gaps in synthetic methodology (Approach 4) [13] [5]. |

Strategic Workflow and Computational Planning

The decision-making process for integrating enzymes into synthesis can be guided by computational tools and a structured workflow. Emerging computational synthesis planning tools, such as those described by [14] and minChemBio [6], are now designed to balance the exploration of enzymatic and synthetic reaction spaces, suggesting hybrid routes that minimize costly transitions between chemical and biological steps.

The following diagram illustrates a strategic workflow for selecting and implementing the appropriate framework, from target analysis to experimental execution.

Framework Selection Workflow

The strategic integration of enzymes into multi-step synthesis, as delineated by the four frameworks presented, provides a powerful and evolving toolbox for the concise and efficient construction of complex molecules. The choice of framework depends on the synthetic challenge: from the tactical resolution of enantiomers (Framework 1) to the hypothesis-driven interrogation of biosynthesis (Framework 2), and further to the strategic use of enzymes to define retrosynthetic logic (Framework 3) or to create entirely new catalytic solutions (Framework 4). As advances in enzyme engineering, immobilization technologies, and computational planning continue to lower the barriers to implementation, these chemoenzymatic strategies are poised to become central methodologies in natural product research and pharmaceutical development, enabling the synthesis of novel analogs with tailored biological activities [4] [18].

The integration of enzymatic transformations into synthetic organic chemistry has fundamentally expanded the toolbox available for the construction of complex molecules. Chemoenzymatic strategies, which combine the precision of biocatalysis with the flexibility of synthetic chemistry, have emerged as particularly powerful approaches for the synthesis and diversification of natural products and pharmaceutical agents [9]. These strategies leverage the exceptional chemo-, regio-, and stereoselectivity of enzymes to perform transformations that are challenging to achieve using traditional chemical methods, often under mild, environmentally benign conditions [9]. Within this framework, oxidoreductases, transferases, and lyases represent three fundamental enzyme classes that enable key bond-forming and functional group interconversion steps. This review provides an in-depth examination of recent advances in applying these enzyme classes to natural product synthesis, with particular emphasis on experimental protocols, reagent solutions, and emerging technological synergies such as machine learning-guided enzyme discovery that are shaping the future of chemoenzymatic synthesis.

Oxidoreductases in Synthesis

Functional Scope and Mechanistic Principles

Oxidoreductases (EC 1) catalyze electron transfer reactions, playing indispensable roles in functional group interconversions and selective C-H activation. According to the Enzyme Commission classification system, this diverse class encompasses oxidases, dehydrogenases, reductases, oxygenases, and peroxidases [21]. Their significance in synthetic chemistry stems from their ability to perform highly selective oxidation and reduction reactions under mild conditions, often with cofactor recycling systems enabling practical synthetic applications.

The industrial relevance of oxidoreductases continues to grow, with them constituting the second largest revenue generator in the global enzymes market after hydrolases [21]. Their value is particularly evident in asymmetric synthesis, where they facilitate the production of chiral building blocks with exceptional enantioselectivity. For instance, ketoreductases (KREDs) have been successfully employed in the synthesis of ipatasertib, a potent protein kinase B inhibitor, where an engineered variant demonstrated a 64-fold increase in apparent kcat and high diastereoselectivity (99.7% de) [9].

Table 1: Major Oxidoreductase Categories and Their Synthetic Applications

| Category | EC Subclass | Characteristic Reaction | Synthetic Application | Example Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidases | EC 1.1-1.3 | Direct transfer of hydrogen to oxygen, producing water or H₂O₂ | Polymer synthesis, biosensors | Laccases, Monoamine oxidases |

| Dehydrogenases | EC 1.4 | Hydride transfer to acceptor substrates | Asymmetric synthesis of chiral alcohols and amines | Alcohol dehydrogenase, Glutamate dehydrogenase |

| Oxygenases | EC 1.13-1.14 | Incorporation of oxygen into substrates | Late-stage functionalization, ring expansion | Cytochrome P450s, α-Ketoglutarate-dependent enzymes |

| Reductases | EC 1.4-1.8 | Reduction of substrates using reduced cofactors | Ketone reduction, reductive amination | Imine reductases, Enoate reductases |

Experimental Protocol: P450-Mediated Skeletal Editing via Ring Expansion

A recent innovative application of oxidoreductases in natural product diversification involves P450-controlled site-selective ring expansion through a chemoenzymatic skeletal editing strategy [4]. This methodology enables precise modification of molecular frameworks at the level of single atoms or bonds, offering powerful opportunities for fine-tuning the biological activity of natural product scaffolds.

Required Materials:

- Engineered P450 enzyme catalyst (divergent regioselectivity variants)

- Natural product substrate (aliphatic C-H containing scaffold)

- Cofactor regeneration system (NADPH/GDH/glucose or equivalent)

- Appropriate reaction buffer (typically phosphate or Tris, pH 7-8)

- Oxygen source (atmospheric O₂ or controlled oxygenation)

- Post-oxidation rearrangement reagents (e.g., for Baeyer-Villiger conditions)

Procedure:

- Enzyme Preparation: Express and purify engineered P450 variants exhibiting divergent regioselectivity toward the target natural product scaffold.

- Biocatalytic Oxidation: Incubate the natural product substrate (0.1-1.0 mM) with the selected P450 catalyst (1-5 mol%) in appropriate buffer containing NADPH-regenerating system at 25-30°C for 4-16 hours with mild agitation.