Foundation Models for Organic Materials Discovery: AI-Driven Approaches from Data to Design

This article explores the transformative role of foundation models in accelerating the discovery of organic materials for applications ranging from organic electronics to drug development.

Foundation Models for Organic Materials Discovery: AI-Driven Approaches from Data to Design

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of foundation models in accelerating the discovery of organic materials for applications ranging from organic electronics to drug development. It provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and scientists, covering the fundamental principles of these AI models, their practical application in property prediction and molecular generation, strategies for overcoming data scarcity and model optimization challenges, and a comparative analysis of their validation against traditional methods. By synthesizing the latest research, this review aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to integrate these powerful tools into their materials discovery workflows, ultimately enabling faster and more efficient innovation.

What Are Foundation Models? Core Concepts and Data Foundations for Organic Materials

Defining Foundation Models and Large Language Models (LLMs) in Materials Science

The field of materials science is undergoing a transformative shift with the emergence of foundation models (FMs) and large language models (LLMs), which are enabling scalable, general-purpose, and multimodal AI systems for scientific discovery. Unlike traditional machine learning models that are narrow in scope and require extensive task-specific engineering, foundation models offer remarkable cross-domain generalization and exhibit emergent capabilities not explicitly programmed during training [1]. Their versatility is particularly well-suited to materials science, where research challenges span diverse data types and scales—from atomic structures to macroscopic properties [1]. These models are catalyzing a new era of data-driven discovery in organic materials research, potentially accelerating the development of novel materials for pharmaceutical applications, energy storage, and sustainable technologies.

Foundation models in materials science are typically defined as large, pretrained models trained on broad, diverse datasets capable of generalizing across multiple downstream tasks with minimal fine-tuning or prompt engineering [2]. The hallmarks of these models include emergent capabilities and the ability to transfer knowledge across domains—for example, from textual descriptions to molecular structures or from property prediction to generative design [1]. This paradigm shift is particularly significant for organic materials discovery, where the complex structure-property relationships have traditionally required extensive experimental validation and computational modeling.

Core Definitions and Technical Foundations

Foundation Models: Architectural Principles and Training Paradigms

Foundation models represent a fundamental shift in AI methodology, characterized by their training on "broad data using self-supervision at scale" and their adaptability "to a wide range of downstream tasks" [2]. The philosophical underpinning of this approach decouples representation learning—the most data-hungry component—from specific task execution, enabling the model to be pretrained once on massive datasets and subsequently fine-tuned for specialized applications with minimal additional training [2].

The transformer architecture, introduced in 2017, serves as the fundamental building block for most foundation models [2]. This architecture has evolved into two predominant variants in materials science applications:

- Encoder-only models: Focused on understanding and representing input data, generating meaningful representations for further processing or predictions. These models are particularly valuable for property prediction and materials classification tasks [2].

- Decoder-only models: Designed to generate new outputs by predicting one token at a time based on given input and previously generated tokens. These excel at generative tasks such as molecular design and synthesis planning [2].

The training process for materials foundation models typically involves three stages: (1) unsupervised pretraining on large amounts of unlabeled data to create a base model, (2) fine-tuning using (often significantly less) labeled data to perform specific tasks, and (3) optional alignment where model outputs are refined to match user preferences, such as generating chemically valid structures with improved synthesizability [2].

Large Language Models: Specialized Adaptations for Materials Science

Large Language Models (LLMs) represent a specialized subclass of foundation models specifically engineered for natural language understanding and generation. In materials science, these models are being adapted to process and generate domain-specific representations, including Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES), SELFIES (Self-Referencing Embedded Strings), and other chemical notations [3].

The remarkable performance of LLMs across diverse tasks they were not explicitly trained on has sparked interest in developing LLM-based agents capable of reasoning, self-reflection, and decision-making for materials discovery [4]. These autonomous agents are typically augmented with tools or action modules, empowering them to go beyond conventional text processing and directly interact with computational environments and experimental systems [4].

Specialized materials science LLMs (MatSci-LLMs) must meet two critical requirements: (1) domain knowledge and grounded reasoning—possessing a fundamental understanding of materials science principles to provide useful information and reason over complex concepts, and (2) augmenting materials scientists—performing useful tasks to accelerate research in a reliable and interpretable manner [5]. Unlike general-purpose LLMs, MatSci-LLMs must be grounded in the physical laws and constraints governing materials behavior, requiring specialized training approaches and architectural considerations.

Quantitative Comparison of Foundation Models and LLMs in Materials Science

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Foundation Models on Materials Discovery Tasks

| Model Name | Primary Architecture | Key Capabilities | Training Data Scale | Notable Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GNoME [1] | Graph Neural Networks | Materials stability prediction | 17 million DFT-labeled structures | Discovered 2.2 million new stable materials |

| MatterSim [1] | Machine-learned interatomic potential | Universal simulation across elements | 17 million DFT-labeled structures | Zero-shot simulation across temperatures/pressures |

| MatterGen [1] | Generative model | Conditional materials generation | Large-scale materials databases | Multi-objective materials generation |

| nach0 [1] | Multimodal FM | Unified natural and chemical language processing | Scientific literature + chemical data | Molecule generation, retrosynthesis, Q&A |

| ChemDFM [1] | Specialized LLM | Scientific literature comprehension | Domain-specific texts | Named entity recognition, synthesis extraction |

Table 2: LLM Agent Frameworks for Materials Design and Discovery

| Framework | LLM Engine | Key Mechanisms | Modification Operations | Target Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLMatDesign [4] | GPT-4o, Gemini-1.0-pro | Self-reflection, history tracking | Addition, removal, substitution, exchange | Band gap engineering, formation energy optimization |

| MatAgent [1] | LLM-based | Tool augmentation, hypothesis generation | Property prediction, experimental analysis | High-performance alloy and polymer discovery |

| HoneyComb [1] | LLM-based | Domain knowledge integration | Data extraction, analysis | General materials science tasks |

| ChatMOF [1] | Autonomous framework | Prediction and generation | Structure modification | Metal-organic frameworks design |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The LLMatDesign Framework: An Autonomous Materials Design Agent

The LLMatDesign framework exemplifies the application of LLMs as autonomous agents for materials discovery. This framework utilizes LLM agents to translate human instructions, apply modifications to materials, and evaluate outcomes using computational tools [4]. The core innovation lies in its ability to incorporate self-reflection on previous decisions, enabling rapid adaptation to new tasks and conditions in a zero-shot manner without requiring large training datasets derived from ab initio calculations [4].

The experimental workflow follows a structured decision loop:

Input Processing: The system accepts chemical composition and target property values as user inputs. If only composition is provided without an initial structure, LLMatDesign automatically queries the Materials Project database to retrieve the corresponding structure, selecting the candidate with the lowest formation energy per atom [4].

Modification Proposal: The LLM agent recommends one of four possible modifications—addition, removal, substitution, or exchange—to the material's composition and structure. These operations serve as proxies for physical processes in materials modification, such as doping or defect creation [4].

Hypothesis Generation: Alongside each modification, the LLM provides a hypothesis explaining the reasoning behind its suggested change, offering interpretability not available in traditional optimization algorithms [4].

Structure Relaxation and Validation: The framework modifies the material based on the suggestion, relaxes the structure using machine learning force fields (MLFFs), and predicts properties using machine learning property predictors (MLPPs) as surrogates for more computationally intensive density functional theory (DFT) calculations [4].

Self-Reflection and History Tracking: If the predicted property doesn't match the target value within a defined threshold, the system evaluates the modification effectiveness through self-reflection. This reflection, along with the modification history, informs subsequent decision cycles [4].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Materials Discovery

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Workflows |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project API [4] | Database Interface | Retrieving crystal structures | Provides initial structures for design campaigns |

| Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFF) [4] | Computational Tool | Structure relaxation | Optimizes atomic coordinates after modifications |

| Machine Learning Property Predictors (MLPP) [4] | Prediction Model | Property estimation | Fast screening of candidate materials |

| DFT Calculations [4] | First-Principles Method | High-fidelity validation | Final verification of promising candidates |

| Open MatSci ML Toolkit [1] | Software Infrastructure | Standardizing graph-based learning | Supporting reproducible materials ML workflows |

Evaluation Metrics and Benchmarking

Rigorous evaluation is essential for assessing the performance of foundation models and LLMs in materials science. For the LLMatDesign framework, researchers employed systematic experiments with starting materials randomly selected from the Materials Project, focusing on two key material properties:

- Band gap targeting: Designing new materials with a band gap of 1.4 eV, representing an ideal photovoltaic material. Success was measured by the average number of modifications required to reach the target within a 10% error tolerance, with a maximum budget of 50 modifications [4].

- Formation energy optimization: Designing new materials with the most negative formation energy possible, indicating higher stability. Performance was evaluated based on the average and minimum formation energies achieved within a fixed budget of 50 modifications [4].

Quantitative results demonstrated that GPT-4o with access to past modification history performed best in achieving the target band gap value, requiring an average of 10.8 modifications compared to 27.4 modifications for random baseline approaches [4]. The inclusion of modification history significantly enhanced performance, with both Gemini-1.0-pro and GPT-4o outperforming their historyless counterparts [4].

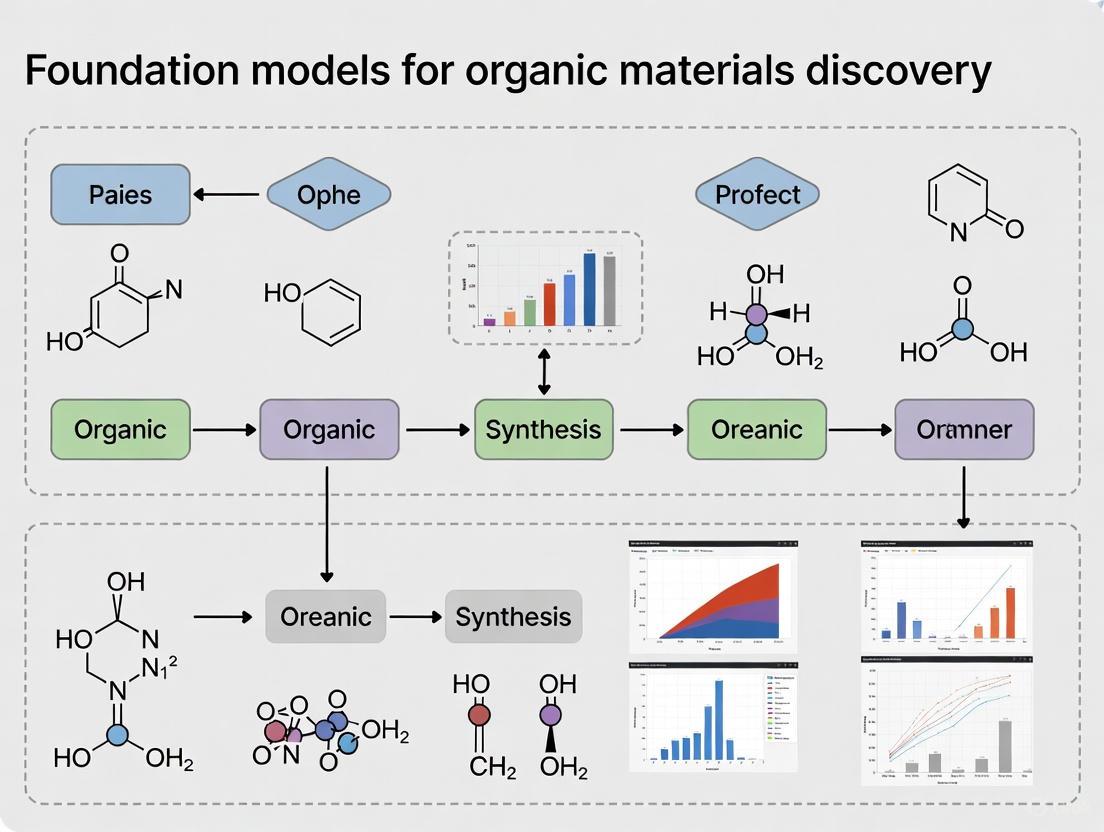

Workflow Visualization: Foundation Models in Materials Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of foundation models and LLM agents in materials discovery, highlighting the interaction between different components and data modalities:

The second diagram details the specific decision-making process of LLM agents within autonomous materials design frameworks:

Current Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite their promising capabilities, foundation models and LLMs in materials science face several significant limitations that must be addressed for broader adoption and impact.

Technical Challenges and Knowledge Gaps

Current LLMs demonstrate substantial gaps in materials science domain knowledge and reasoning capabilities. In comprehensive testing, modern LLMs including GPT-4 failed to adequately answer 650 undergraduate materials science questions even with chain-of-thought prompting, indicating fundamental deficiencies in understanding domain-specific concepts [5]. Specific failure cases include:

- Incorrect crystal symmetry reasoning: LLMs often misapply principles of crystal symmetry when determining piezoelectric and ferroelectric properties [5].

- Faulty mathematical reasoning: Errors in applying selection rules for Miller indices in X-ray diffraction patterns, despite understanding the underlying principles [5].

- Limited multimodal fusion: Challenges in effectively integrating structural, textual, and spectral data [1].

- Data imbalance and quality issues: Limited labeled data compared to natural language domains, with materials data being costly to generate and often imbalanced [1].

Future Research Trajectories

The evolution of foundation models for materials discovery is advancing along several key research directions:

- Scalable pretraining methodologies: Developing more efficient approaches for training on increasingly diverse and multimodal materials data [1].

- Continual learning frameworks: Enabling models to adapt to new experimental data and scientific discoveries without catastrophic forgetting [1].

- Enhanced reasoning capabilities: Improving logical and physical reasoning through specialized architectures and training techniques [5].

- Data governance and quality: Establishing standards for high-quality, curated datasets specifically designed for materials foundation model training [1] [5].

- Trustworthiness and interpretability: Developing methods to enhance model transparency and reliability for scientific applications [1].

As these technical challenges are addressed, foundation models and LLMs are poised to become indispensable tools in the materials scientist's toolkit, potentially transforming the pace and nature of organic materials discovery in pharmaceutical research and development.

The transformer architecture has emerged as a foundational framework for constructing chemical foundation models, enabling significant advances in molecular property prediction, de novo molecular design, and synthesis planning. By adapting core components like self-attention mechanisms to incorporate domain-specific inductive biases—including molecular graph structure, three-dimensional geometry, and reaction constraints—transformers overcome limitations of traditional string-based representations and task-specific models. This technical guide examines the architectural innovations, experimental methodologies, and application pipelines that position transformer-based models as the central engine for next-generation organic materials discovery, facilitating more interpretable, data-efficient, and trustworthy research tools.

In natural language processing, the transformer architecture, introduced by Vaswani et al., has become the standard due to its self-attention mechanism that captures long-range dependencies without recurrent layers [6]. The materials science and chemistry domains have adopted this architecture, leading to a paradigm shift from hand-crafted feature engineering and task-specific models toward general-purpose, pre-trained foundation models that can be adapted to diverse downstream tasks with minimal fine-tuning [2] [1].

Chemical foundation models built on transformers are typically trained on broad data—such as massive molecular databases like PubChem and ZINC—using self-supervision, and can then be fine-tuned for specific applications ranging from quantum property prediction to synthesizable molecular generation [2] [7]. This approach decouples data-hungry representation learning from target task adaptation, enhancing data efficiency—a critical advantage in domains where labeled experimental data is scarce and costly [6]. The versatility of the transformer is evidenced by its dual role as both a powerful feature extractor (encoder) and a generative engine (decoder), making it uniquely suited for the predictive and generative challenges inherent in organic materials discovery [2].

Core Architectural Adaptations for Molecular Data

The standard transformer architecture requires significant modifications to effectively process molecular information. These adaptations integrate critical chemical domain knowledge directly into the model's inductive bias.

Molecular Representation and Tokenization

Transformers process molecules through various representations, each with distinct trade-offs between structural fidelity and sequence-based processability.

- SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System): A linear string encoding of a molecule's structure. While widely used, its limitation is that a single atom change can completely alter the sequence order, making it difficult for the model to learn spatial or graph-based relationships directly [6].

- SELFIES (Self-Referencing Embedded Strings): A more robust string-based representation designed to always generate syntactically valid molecular structures, mitigating a key weakness of SMILES [7].

- Molecular Graphs: Represent atoms as nodes and bonds as edges. This representation explicitly encodes the fundamental structure of a molecule but requires graph-based neural network layers or specialized attention to process [7].

- 3D Representations: Capture the spatial coordinates of atoms, which are crucial for determining many physicochemical properties. These can be represented as 3D atom positions or 3D density grids [7].

- Specialized Encodings (e.g., MOFid): For complex materials like Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), hybrid representations like MOFid combine SMILES notations of building blocks with topological codes, enabling a single sequence to capture both chemistry and structure [8].

Specialized Self-Attention Mechanisms

The self-attention mechanism is the core of the transformer. Several novel variants have been developed to incorporate chemical structural information.

Molecule Attention Transformer (MAT) enhances standard self-attention by incorporating inter-atomic distances and molecular graph structure. Its attention mechanism is calculated as [9]:

Attention(X) = (λ_a * Softmax(QK^T/√d_k) + λ_d * g(D) + λ_g * A) V

Where:

Q,K,Vare the Query, Key, and Value matrices from the input embedding X.g(D)is a function (e.g., softmax or exponential) of the distance matrix D.Ais the graph adjacency matrix.λ_a,λ_d,λ_gare learnable weights balancing the contribution of standard attention, distance, and graph connectivity [9].

Relative Molecule Self-Attention Transformer (R-MAT) further advances this concept by fusing both distance and graph neighborhood information directly into the self-attention computation using relative positional encodings, which have proven effective in other domains like protein design [6]. This allows the model to more effectively reason about the 3D conformation of a molecule, a key factor in property prediction [6].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Transformer Architectures in Chemistry

| Model Name | Core Innovation | Molecular Representation | Key Incorporated Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecule Attention Transformer (MAT) [9] [6] | Augments attention with distance and graph | Molecular Graph | Interatomic distances, bond adjacency |

| Relative MAT (R-MAT) [6] | Relative self-attention for molecules | Molecular Graph + 3D Conformation | 3D distances, graph neighborhoods |

| MATERIALS FM4M (SMI-TED) [7] | Encoder-decoder for sequences | SMILES | Learned semantic tokens from large-scale SMILES data |

| MOFGPT [8] | GPT-based generator for MOFs | MOFid (SMILES + Topology) | Chemical building blocks, topological codes |

| TRACER [10] | Conditional transformer for reactions | SMILES (Reaction-based) | Reaction type constraints |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The development and validation of transformer-based chemical foundation models follow rigorous experimental pipelines. Key methodological components are detailed below.

Pre-training Strategies

Pre-training is a critical first step for building effective foundation models. The most common pre-training tasks are designed to be self-supervised, learning from unlabeled molecular data.

- Local Atom Context Masking: Inspired by BERT's masked language modeling, this approach randomly masks atoms or tokens in a molecular sequence (SMILES, SELFIES) or graph and tasks the model with predicting them based on their context. This forces the model to learn robust, context-aware representations of atoms and substructures [6].

- Global Graph-Based Prediction: This involves auxiliary tasks that require predicting global molecular properties from the representation, such as molecular weight or the presence of specific functional groups. This encourages the model to capture both local and global structural information [6].

Model Fine-tuning for Downstream Tasks

After pre-training, models are adapted to specific tasks (e.g., predicting toxicity or binding affinity) via fine-tuning. This involves training the pre-trained model on a smaller, labeled dataset for the target task, allowing it to leverage its general molecular knowledge while specializing. The fm4m-kit from IBM's FM4M project exemplifies this, providing a wrapper to easily extract representations from uni-modal models (e.g., SMI-TED, MHG-GED) and train a downstream predictor like XGBoost for regression or classification [7].

Reinforcement Learning for Molecular Optimization

For generative tasks, reinforcement learning (RL) is used to steer sequence generation toward molecules with desirable properties. The framework, as implemented in models like MOFGPT and TRACER, typically involves three components [8] [10]:

- Generator: A transformer-based decoder (e.g., a GPT model) that generates molecular sequences.

- Predictor: A property prediction model (e.g., a transformer-based regressor) that scores generated molecules against a target property.

- RL Algorithm: A policy gradient method (e.g., Proximal Policy Optimization) that uses the predictor's score as a reward to update the generator, increasing the probability of generating high-scoring molecules.

Table 2: Key Experimental Datasets and Benchmarks

| Dataset Name | Scale and Content | Primary Use Case | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubChem [2] [7] | ~109 molecules | Large-scale pre-training | Public Database |

| ZINC [2] [7] | ~109 commercially available compounds | Pre-training & generative benchmarking | Public Database |

| USPTO [10] | Thousands of chemical reactions | Reaction prediction & conditional generation | Patent Data |

| hMOF & QMOF [8] | Hundreds of thousands of MOF structures | MOF property prediction & generation | Curated Computational Databases |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key computational "reagents" and resources essential for building and experimenting with chemical foundation models.

Table 3: Key Resources for Developing Chemical Foundation Models

| Resource Name | Type | Function | Example/Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES/SELFIES | Molecular Representation | Converts molecular structure into a sequence of tokens for transformer processing. | [6] [7] |

| Molecular Graph | Molecular Representation | Represents atoms as nodes and bonds as edges for graph-based transformers. | [7] [9] |

| Reaction Templates | Conditional Token | Provides constraints for transformer models to ensure chemically plausible product generation. | [10] |

| MOFid | Specialized Representation | Encodes Metal-Organic Framework structure and topology into a single string for generative modeling. | [8] |

| fm4m-kit | Software Toolkit | A wrapper toolkit to access and evaluate IBM's multi-modal foundation models for materials. | [7] |

| Open MatSci ML Toolkit | Software Infrastructure | Standardizes graph-based materials learning workflows for model development and training. | [1] |

Applications in Organic Materials Discovery

Transformer-based foundation models are deployed across the materials discovery pipeline, demonstrating significant impact in key areas.

Property Prediction

Transformer encoders, fine-tuned on specific labeled data, achieve state-of-the-art performance in predicting molecular properties like toxicity, solubility, and electronic band gaps. For example, the R-MAT model leverages 3D structural information to achieve competitive accuracy without extensive hand-crafted features, proving particularly effective on small datasets common in drug discovery [6]. IBM's FM4M project showcases how uni-modal models (e.g., POS-EGNN for 3D structures) or fused multi-modal models can be used for highly accurate quantum property prediction [7].

De Novo Molecular Generation and Optimization

Decoder-only transformer architectures, similar to GPT, are used to generate novel molecular structures. When combined with RL, this enables inverse design—creating molecules tailored to specific property profiles.

- TRACER: This framework uses a conditional transformer to predict products from reactants under a specific reaction type constraint. It is then guided by a Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm to explore the chemical space and generate compounds with high predicted activity against targets like DRD2 and AKT1, while considering synthetic feasibility [10].

- MOFGPT: This model uses a GPT-2 architecture trained on MOFid sequences. It is then fine-tuned with RL to generate novel, valid Metal-Organic Frameworks with targeted properties, such as high CO2 adsorption capacity or specific electronic band gaps [8].

Synthesis-Aware Design

A major advancement is the integration of synthesis planning into molecular generation. The TRACER model explicitly addresses the critical question of "how to make" a generated compound, not just "what to make." By learning from reaction databases, its conditional transformer can propose realistic synthetic pathways, moving beyond topological synthesisability scores to data-driven reaction prediction [10]. This capability is vital for translating computational designs into bench-side synthesis.

The transformer architecture, through targeted innovations in self-attention and molecular representation, has firmly established itself as the core engine of chemical foundation models. Its ability to seamlessly unify property prediction, de novo generation, and synthesis planning within a single, adaptable framework is accelerating a fundamental shift in organic materials discovery. By encoding chemical principles directly into the model's inductive bias, these systems are evolving from black-box predictors into interpretable and trustworthy partners for researchers. As the field progresses, the integration of ever-larger and more diverse multimodal data, coupled with advanced training paradigms like federated learning and agentic AI, promises to further enhance the scope and impact of transformer-driven discovery, ultimately compressing the timeline from conceptual design to realized material.

The choice of data representation is a foundational challenge in applying artificial intelligence to organic materials discovery. Foundation models, trained on broad data and adapted to diverse downstream tasks, are revolutionizing the field, but their effectiveness is intrinsically linked to how molecular information is encoded [11]. In scientific domains, where minute structural details can profoundly influence material properties—a phenomenon known as an "activity cliff"—the selection of an appropriate molecular representation becomes particularly critical [11]. This technical guide examines the key data modalities—from ubiquitous string-based representations to emerging algebraic approaches—within the context of foundation models for organic materials research, providing researchers with a framework for selecting representations based on specific task requirements in drug development and materials science.

String-Based Molecular Representations

SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System)

SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) represents chemical structures using ASCII strings that describe atomic elements and bonds through a specific grammar [12]. This method provides a concise, human-readable format that has become one of the most widely adopted representations in cheminformatics databases such as PubChem and ZINC [12] [13].

Despite its widespread use, SMILES exhibits significant limitations for machine learning applications. The representation can generate semantically invalid strings when used in generative models, often resulting in invalid molecular outputs that hamper automated discovery approaches [12]. SMILES also demonstrates inconsistency in representing isomers, where a single string may correspond to multiple molecules, or different strings may represent the same molecule, creating ambiguity in comparative studies and database searches [12]. Additionally, SMILES struggles to represent certain chemical classes including organometallic compounds and complex biological molecules [12]. Perhaps most fundamentally, as a text-based representation, SMILES reduces three-dimensional molecules to lines of text, causing valuable structural information to be lost [13].

SELFIES (SELF-referencing Embedded Strings)

SELFIES (SELF-referencing Embedded Strings) was developed specifically to address key limitations of SMILES in cheminformatics and machine learning applications [12]. Unlike SMILES, every valid SELFIES string guarantees a semantically valid molecular representation, a crucial robustness property for computational chemistry applications in molecule design using models like Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [12].

Experimental evidence demonstrates SELFIES's superiority in generative tasks. Where SMILES often generates invalid strings when mutated, SELFIES consistently produces valid molecules with random string mutations [12]. The latent space of SELFIES-based VAEs is denser than that of SMILES by two orders of magnitude, enabling more comprehensive exploration of chemical space during optimization procedures [12]. This representation has shown particular advantages in producing diverse and complex molecules while maintaining chemical validity.

Tokenization Strategies for Chemical Languages

The effectiveness of string-based representations in transformer models depends significantly on tokenization strategies. Traditional Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) has limitations when applied to chemical languages like SMILES and SELFIES, often failing to capture contextual relationships necessary for accurate molecular representation [12].

Recent research introduces Atom Pair Encoding (APE), a novel tokenization approach specifically designed for chemical languages [12]. APE preserves the integrity and contextual relationships among chemical elements more effectively than BPE, significantly enhancing classification accuracy in downstream tasks [12]. Evaluations using biophysics and physiology datasets for HIV, toxicology, and blood-brain barrier penetration classification demonstrate that models utilizing APE tokenization outperform state-of-the-art approaches, providing a new benchmark for chemical language modeling [12].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of String-Based Molecular Representations

| Feature | SMILES | SELFIES |

|---|---|---|

| Validity Guarantee | No - can generate invalid structures | Yes - always produces valid molecules |

| Representational Capability | Limited for complex bonding systems | Robust for standard organic molecules |

| 3D Structural Information | None - purely 2D representation | None - purely 2D representation |

| Generative Model Performance | Prone to invalid outputs | Higher validity rates in mutation tasks |

| Latent Space Density | Less dense in VAEs | Two orders of magnitude denser in VAEs |

| Tokenization Compatibility | Works with BPE, better with APE | Works with BPE, better with APE |

Advanced Structural Representations

Molecular Graphs and Beyond

Molecular graphs represent atoms as vertices and bonds as edges, providing a more natural structural representation than strings [14]. This approach enables direct application of insights from chemical graph theory in machine learning models and better preserves spatial relationships between atomic constituents [14]. However, standard molecular graphs face limitations representing complex bonding phenomena including delocalized electrons, multi-center bonds, organometallics, and resonant structures [14].

Molecular hypergraphs extend graph representations with edges that can connect any number of vertices, potentially addressing delocalized bonding [14]. However, as Dietz notes, "A hyperedge containing more than two atoms gives us no information about the binary neighborhood relationships between them," essentially representing an electronic "soup" without specifying how electrons are delocalized [14]. Multigraphs offer another alternative but remain uncommon in practical implementations despite their theoretical advantages for representing complex bonding scenarios [14].

Algebraic Data Types: A Paradigm Shift

Algebraic Data Types (ADTs) represent an emerging paradigm that implements the Dietz representation for molecular constitution via multigraphs of electron valence information while incorporating 3D coordinate data to provide stereochemical information [14]. This approach significantly expands representational scope compared to traditional methods, easily enabling representation of complex molecular phenomena including organometallics, multi-center bonds, delocalized electrons, and resonant structures [14].

The ADT framework distinguishes between three representation types: storage representations (format for on-disk storage), transmission representations (how molecules are sent between researchers), and computational representations (how molecules are represented inside programming languages) [14]. This distinction is crucial in cheminformatics, as the data type constrains possible operations, reflects data structure and semantics, and affects computational efficiency [14]. Unlike string-based representations, ADTs provide type safety and seamless integration with Bayesian probabilistic programming, offering a robust platform for innovative cheminformatics research [14].

Table 2: Structural Representation Modalities for Foundation Models

| Representation Type | Strengths | Limitations | Foundation Model Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Graphs | Natural structural representation; Enables graph theory applications | Limited for complex bonding; No 3D information | Property prediction; Molecular generation |

| Molecular Hypergraphs | Can represent delocalized bonding | Does not specify electron distribution; Uncommon in practice | Specialized applications for complex bonding |

| 3D Geometric | Captures spatial conformation; Enables energy prediction | Computationally expensive; Limited datasets | Quantum property prediction; Conformational analysis |

| Algebraic Data Types | Comprehensive bonding representation; Type-safe; Quantum information | Early development stage; Limited tooling | Probabilistic programming; Reaction modeling |

Spectroscopic Data as a Multimodal Component

Experimental spectroscopic data provides crucial empirical evidence about molecular behavior and electronic structure, serving as a valuable multimodal component in foundation models. Key spectral types include Infrared (IR) and Raman spectra, which provide vibrational "fingerprints" of molecules; Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectra, particularly 1H and 13C, offering structural information through nuclear spin interactions; Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectra, revealing electronic excitation patterns; and Mass Spectrometry (MS) data, providing molecular mass and fragmentation information [15] [16] [17].

Several comprehensive databases provide curated spectral data, including the Spectral Database for Organic Compounds (SDBS) containing over 34,000 organic molecules [15], NIST Chemistry WebBook offering IR, mass, electronic/vibrational, and UV/Vis spectra [16], and Reaxys containing extensive spectral data for organic and inorganic compounds excerpted from journal literature [16]. These resources serve as critical training data sources for spectroscopic prediction models.

AI-Driven Spectral Prediction

Deep learning approaches now enable accurate prediction of molecular spectra from structural information, dramatically accelerating spectral identification. The DetaNet framework demonstrates particular promise, combining E(3)-equivariance group and self-attention mechanisms to predict multiple spectral types with quantum chemical accuracy [17]. This architecture achieves remarkable predictive performance, with over 99% accuracy for IR, Raman, and NMR spectra, and 92% accuracy for UV-Vis spectra [17].

The efficiency improvements are equally significant, with DetaNet improving prediction efficiency by three to five orders of magnitude compared to traditional quantum chemical methods employing density functional theory (DFT) [17]. For vibrational spectroscopy, DetaNet calculates Hessian matrices with 99.94% accuracy compared to DFT references, enabling precise prediction of IR and Raman intensities through derivatives of dipole moment and polarizability tensor with respect to normal coordinates [17].

Multimodal Fusion in Foundation Models

The Multimodal Imperative

Real-world material systems exhibit multiscale complexity with heterogeneous data types spanning composition, processing, microstructure, and properties [18]. This inherent multimodality creates significant challenges for AI modeling, particularly given that material datasets are frequently incomplete due to experimental constraints and the high cost of acquiring certain measurements [18]. Multimodal learning (MML) frameworks address these challenges by integrating and processing multiple data types, enhancing model understanding of complex material systems while mitigating data scarcity issues [18].

Approaches like MatMCL (Multimodal Contrastive Learning for Materials) demonstrate the power of structure-guided pre-training strategies that align processing and structural modalities via fused material representations [18]. By guiding models to capture structural features, these approaches enhance representation learning and mitigate the impact of missing modalities, ultimately boosting material property prediction performance [18].

Mixture of Experts Architectures

Mixture of Experts (MoE) architectures have emerged as a powerful framework for fusing complementary molecular representations in foundation models. IBM Research's multi-view MoE architecture combines embeddings from SMILES, SELFIES, and molecular graph-based models, outperforming unimodal approaches on standardized benchmarks [13]. This architecture employs a routing algorithm that selectively activates specialized "expert" networks based on the specific task, dynamically leveraging the strengths of each representation modality [13].

Research reveals that MoE architectures naturally learn to favor specific representations for different task types. SMILES and SELFIES-based models receive preferential activation for certain classification tasks, while the graph-based model adds predictive value for other problem types, particularly those requiring structural awareness [13]. This adaptive expert activation pattern demonstrates how MoE architectures can effectively tailor representation usage to specific chemical problems without manual intervention.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Molecular Representation and Spectroscopy

| Resource | Type | Key Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubChem | Database | Large-scale repository of chemical structures and properties | Public |

| ZINC | Database | Commercially-available chemical compounds for virtual screening | Public |

| SDBS | Spectral Database | Integrated spectral database system for organic compounds | Public with registration |

| NIST Chemistry WebBook | Spectral Database | Critically evaluated IR, mass, UV/Vis spectra, and thermochemical data | Public |

| Reaxys | Database | Extensive chemical substance, reaction, and spectral data | Subscription |

| QM9/QSMR | Dataset | Quantum chemical properties for 130,000 small organic molecules | Public |

| IBM FM4M Models | Foundation Models | Open-source foundation models for materials discovery | GitHub/Hugging Face |

| DetaNet | Deep Learning Model | Spectral prediction with quantum chemical accuracy | Research implementation |

Multimodal Framework Implementation

The MatMCL framework implementation provides a instructive case study for multimodal materials learning. The structure-guided pre-training employs three encoder types: a table encoder modeling nonlinear effects of processing parameters, a vision encoder learning microstructural features directly from raw SEM images, and a multimodal encoder integrating processing and structural information [18]. For each sample in a batch of N materials, the processing conditions ({{{\bf{x}}}{i}^{{\rm{t}}}}}{i=1}^{N}), microstructure ({{{\bf{x}}}{i}^{{\rm{v}}}}}{i=1}^{N}), and fused inputs ({{{\bf{x}}}{i}^{{\rm{t}}},{{\bf{x}}}{i}^{{\rm{v}}}}}{i=1}^{N}) are processed by their respective encoders, producing learned representations ({{{\bf{h}}}{i}^{{\rm{t}}}}}{i=1}^{N},{{{\bf{h}}}{i}^{{\rm{v}}}}}{i=1}^{N},{{{\bf{h}}}{i}^{{\rm{m}}}}}_{i=1}^{N}) [18].

A shared projector (g(\cdot )) maps these encoded representations into a joint space for multimodal contrastive learning, producing three representation sets ({{{\bf{z}}}{i}^{{\rm{t}}}}}{i=1}^{N},{{{\bf{z}}}{i}^{{\rm{v}}}}}{i=1}^{N},{{{\bf{z}}}{i}^{{\rm{m}}}}}{i=1}^{N}) [18]. The fused representations serve as anchors in contrastive learning, aligned with corresponding unimodal embeddings as positive pairs while embeddings from other samples serve as negatives. A contrastive loss jointly trains encoders and projector by maximizing agreement between positive pairs while minimizing it for negative pairs [18]. This approach enables robust property prediction even when structural information is missing during inference.

Workflow Visualization

Molecular Representation to Task Pipeline

The evolution of molecular representations from simple string-based encodings to sophisticated multimodal frameworks reflects the increasing demands of foundation models in organic materials discovery. No single representation currently dominates all applications; rather, researchers must select representations based on specific task requirements, data availability, and computational constraints. String-based representations like SELFIES offer computational efficiency for high-throughput screening, while graph-based approaches provide richer structural information at greater computational cost. Emerging approaches like Algebraic Data Types promise unprecedented representational scope but require further development of supporting tooling and integration with existing workflows.

The future of molecular representation lies not in identifying a single superior format, but in developing increasingly sophisticated fusion techniques that leverage the complementary strengths of multiple modalities. As foundation models continue to mature in materials science, representations that seamlessly integrate structural, spectroscopic, and synthesis information will unlock new capabilities in inverse design and autonomous discovery, ultimately accelerating the development of novel organic materials for pharmaceutical, energy, and sustainability applications.

The activity cliff (AC) phenomenon, where miniscule structural modifications to a molecule lead to dramatic changes in its biological activity, presents a fundamental challenge to the reliability of predictive models in drug discovery and materials science [19] [20]. These cliffs create sharp discontinuities in the structure-activity relationship (SAR) landscape, directly contradicting the traditional similarity principle that underpins many computational approaches [21]. This technical guide elucidates how activity cliffs compromise even sophisticated machine learning models and posits that their mitigation is not primarily a question of algorithmic complexity, but of data quality, richness, and representation. Within the emerging paradigm of foundation models for organic materials discovery, overcoming this hurdle is a critical prerequisite for building robust, generalizable, and predictive AI systems.

An activity cliff is formally defined as a pair of structurally similar compounds that exhibit a large difference in potency for the same biological target [19] [21]. The most common quantitative descriptor for identifying ACs is the Structure-Activity Landscape Index (SALI), which is calculated as:

SALI(i, j) = |Pi - Pj| / (1 - s_ij) [21]

where P_i and P_j are the property values (e.g., binding affinity) of molecules i and j, and s_ij is their structural similarity, typically measured by the Tanimoto coefficient using molecular fingerprints [21]. A high SALI value indicates a steep activity cliff. However, this formulation has inherent mathematical limitations, including being undefined when similarity equals 1, prompting the development of improved metrics like the Taylor Series-based SALI and the linear-complexity iCliff index for quantifying landscape roughness across entire datasets [21].

Table 1: Common Methodologies for Defining and Identifying Activity Cliffs

| Method | Core Principle | Key Metric(s) | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Similarity-Based (Tanimoto) | Computes similarity from molecular fingerprints or descriptors [20]. | Tanimoto Similarity, SALI [21]. | Flexible, can find multi-point similarities [20]. | Threshold-dependent; different fingerprints yield low consensus [20]. |

| Matched Molecular Pairs (MMPs) | Identifies pairs identical except at a single site (a specific substructure) [20] [22]. | Potency Difference (e.g., ΔpKi). | Intuitive, interpretable transformations; low false-positive rate [20]. | Can miss highly similar molecules with multiple small differences [20]. |

Why Activity Cliffs Undermine AI-Driven Discovery

Activity cliffs form a major roadblock for Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling and modern machine learning. The core issue is that these models are often trained on the principle of molecular similarity, learning that structurally close molecules should have similar properties. ACs are stark exceptions to this rule, and their statistical underrepresentation in training data leads to significant prediction errors [19] [22].

Experimental Evidence of Model Failure

Systematic studies have demonstrated that QSAR models exhibit low sensitivity towards activity cliffs. This failure mode is persistent across diverse model architectures:

- A landmark study evaluating nine distinct QSAR models combining different representations (ECFPs, descriptor vectors, Graph Isomorphism Networks) and algorithms (Random Forests, k-Nearest Neighbors, MLPs) found they frequently failed to predict ACs. Performance only substantially improved when the actual activity of one compound in the pair was provided, highlighting the model's inherent difficulty with the cliff itself [19].

- This performance drop is observed not only in classical descriptor-based models but also in highly nonlinear and adaptive deep learning models. Counterintuitively, some evidence suggests that classical methods can even outperform complex deep learning on "cliffy" compounds [19].

- The problem extends to molecular generation. Standard benchmarks and scoring functions for de novo drug design often lack realistic discontinuities, leading to algorithms that perform well in simulation but may fail in real-world applications where activity cliffs are prevalent [22].

The Path to Solutions: From Improved Indices to Cliff-Aware AI

Overcoming the activity cliff problem requires innovations on two fronts: better quantification of the phenomenon itself and novel AI frameworks that explicitly account for SAR discontinuities.

Advanced Methodologies for Activity Cliff Analysis

Mathematical Reformulation: The iCliff Framework To address the computational and mathematical limitations of SALI (unboundedness, undefined at s_ij=1, O(N²) complexity), the iCliff index was developed [21]. Its calculation leverages the iSIM (instant similarity) framework for linear-complexity computation of average molecular similarity in a set.

Core Protocol: Calculating the iCliff Index

- Calculate Mean Squared Property Difference: Compute the variance of the molecular properties (e.g., pKi) across the dataset. This is an O(N) operation, as shown in Equation 7 of the theory [21]:

(1/N²) * ΣΣ (P_i - P_j)² = 2 * [ (ΣP_i²)/N - (ΣP_i/N)² ] - Compute Average Similarity: Calculate the average pairwise Tanimoto similarity for the set using the iSIM formalism, which aggregates bit counts across all fingerprints, also in O(N) time [21].

- Combine Components: The final iCliff value is obtained by multiplying the mean squared property difference by a Taylor-series term derived from the average similarity. A higher iCliff value indicates a rougher, more cliff-laden activity landscape [21].

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating QSAR Model Performance on Activity Cliffs

- Data Curation: Select a dataset with known activity cliffs (e.g., from ChEMBL). Identify AC pairs using a defined threshold (e.g., Tanimoto similarity > 0.6 and potency difference > 100-fold or 2 log units) [20].

- Model Training: Train a suite of QSAR models (e.g., ECFP-RF, GIN-MLP) on a training set, ensuring some "cliffy" compounds are held out in the test set.

- Performance Assessment:

- General QSAR Performance: Evaluate standard metrics (R², RMSE) on a standard test set.

- AC Sensitivity: Calculate the sensitivity (true positive rate) of the model in correctly classifying pairs of similar compounds as activity cliffs or non-cliffs [19].

- Cliffy Compound Prediction: Compare the prediction error for compounds involved in activity cliffs versus "smooth" regions of the SAR landscape [19].

Activity Cliff-Aware AI Foundation Models

The next frontier is moving from passive identification to active integration of AC knowledge into AI systems, particularly foundation models.

The ACARL Framework: The Activity Cliff-Aware Reinforcement Learning (ACARL) framework is a pioneering approach for de novo molecular design that explicitly models activity cliffs [22].

- Activity Cliff Index (ACI): A quantitative metric integrated into the RL environment to identify molecules that participate in activity cliffs based on their structural neighbors and activity differences [22].

- Contrastive Loss: A tailored loss function within the reinforcement learning agent that amplifies the learning signal from activity cliff compounds. This forces the generative model to focus on these high-impact, high-discontinuity regions of the chemical space, optimizing for the generation of novel compounds with targeted, potent properties [22].

Multi-Modal Foundation Models: IBM's foundation models for materials (FM4M) represent a complementary strategy. They pre-train separate models on different molecular representations—SMILES/SELFIES (text-based), molecular graphs (structure-based), and spectroscopic data—and then fuse them using a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architecture [13]. This "multi-view" approach allows the model to leverage the strengths of each representation. For instance, the graph-based model may be more sensitive to subtle structural changes that cause cliffs, while the SMILES-based model captures broader patterns. This richness of representation is a key defense against the oversimplifications that lead to AC-related errors [13].

Diagram 1: The ACARL Framework for cliff-aware molecular generation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for AC Research

Table 2: Key Research Reagents & Computational Tools

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Primary Function in AC Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs) | Molecular Representation | Encodes molecular structure into a fixed-length bit vector; used to calculate Tanimoto similarity for AC identification [19]. | Resolution (e.g., ECFP4, ECFP6) significantly impacts which pairs are deemed similar [20]. |

| Tanimoto Coefficient | Similarity Metric | Quantifies the structural similarity between two molecular fingerprints; a core component of the SALI index [21] [20]. | No universal threshold for "similar"; optimal range is dataset- and representation-dependent [21]. |

| ChEMBL Database | Data Source | A vast, open-source repository of bioactive molecules with binding affinities (Ki, IC50) for training and validating models [19] [22]. | Data must be curated and standardized; activity values from different assays are not directly comparable [20]. |

| iCliff / SALI Index | Analytical Metric | Quantifies the intensity of an individual AC (SALI) or the overall roughness of a dataset's activity landscape (iCliff) [21]. | SALI is undefined for identical molecules; iCliff offers linear computational complexity [21]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GINs) | AI Model | A deep learning architecture that operates directly on molecular graph structures, competitive with ECFPs for AC classification [19]. | Can capture structural nuances potentially missed by fixed fingerprints [19]. |

| Docking Software (AutoDock, etc.) | Computational Oracle | Provides a structure-based scoring function (docking score) that can authentically reflect activity cliffs, useful for evaluating generative models [22]. | Scoring functions are approximations; results require careful interpretation and validation. |

Diagram 2: Data remediation pipeline for building robust foundation models.

The challenge of the activity cliff is a powerful illustration that in the age of AI-driven science, the quality and structure of data are as critical as the algorithms themselves. The evidence is clear: simply building larger or more complex models on existing, cliff-prone data is insufficient [19] [22]. The path forward requires a concerted effort to build the next generation of foundational datasets for materials science—datasets that are not only large but also richly annotated, multi-modal, and strategically enriched with characterized activity cliffs. By embracing cliff-aware modeling frameworks like ACARL and leveraging multi-modal fusion strategies, the research community can transform the activity cliff from a persistent obstacle into a source of deep SAR insight, ultimately accelerating the discovery of novel organic materials and therapeutics.

The advent of foundation models in artificial intelligence has revolutionized numerous scientific fields, including materials discovery and drug development. These models, characterized by training on broad data at scale and adaptation to diverse downstream tasks, require massive volumes of high-quality, structured information for effective pre-training. Public chemical and materials databases serve as foundational pillars in this ecosystem, providing the critical data infrastructure necessary for building robust, generalizable AI models. The strategic selection and utilization of these databases directly influences model performance, interpretability, and practical utility in real-world discovery pipelines. Among the numerous available resources, four databases stand out for their scale, quality, and relevance: PubChem, ZINC, ChEMBL, and the Clean Energy Project Database (CEPDB). Each offers unique characteristics—from drug-like small molecules in PubChem and ChEMBL to purchasable chemical space in ZINC and organic electronic materials in CEPDB—that make them indispensable for comprehensive model pre-training. This technical guide examines the core attributes of these databases, their synergistic value in training foundation models, and practical methodologies for their integration into materials discovery research, providing scientists with a framework for leveraging these public resources to accelerate innovation.

Database Core Characteristics and Technical Specifications

Comparative Analysis of Major Databases

Table 1: Core characteristics and specifications of major public databases for foundation model pre-training.

| Database | Primary Focus | Data Content & Scale | Key Features for AI Pre-training | Data Types & Modalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubChem | Small molecules & biological activities | • 97.6M+ unique chemical structures• 264.8M+ bioactivity test results• 1.3M+ biological assays• 10,000+ protein targets [23] [24] | • Drug/lead-like compound filters• Patent linkage information• Standardized chemical representations• Multiple programmatic access points | • Chemical structures• Bioactivity data• Assay results• 3D conformers• Annotation data |

| ChEMBL | Bioactive molecules with drug-like properties | • Manually curated bioactivity data• Chemical probe annotations• SARS-CoV-2 screening data• Action type annotations [25] | • High-quality manual curation• Experimental binding data• Target-focused organization• Natural product annotations | • Binding affinities• ADMET properties• Target information• Mechanism of action |

| ZINC | Purchasable compounds for virtual screening | • 230M+ ready-to-dock, 3D compounds• 750M+ purchasable compounds for analog searching• Multi-billion scale make-on-demand libraries [26] [27] | • Commercially accessible compounds• Pre-computed physical properties• Ready-to-dock 3D formats• Sublinear similarity search | • 3D molecular conformations• Partial atomic charges• cLogP values• Solvation energies |

| CEPDB | Organic photovoltaics & electronics | • 2.3M molecular graphs• 22M geometries• 150M DFT calculations• 400TB of data [28] | • High-throughput DFT data• Electronic property calculations• Experimental data integration• OPV-specific design parameters | • DFT calculations• Electronic properties• Optical characteristics• Crystal structures |

Domain Specialization and Data Characteristics

Each database exhibits distinct domain specialization that dictates its optimal use in foundation model training. PubChem serves as a comprehensive chemical data universe with particular strength in biologically relevant compounds, with approximately 75% of its 97.6 million compounds classified as "drug-like" according to Lipinski's Rule of Five, and 11% meeting stricter "lead-like" criteria [24]. This makes it particularly valuable for models targeting drug discovery applications. The database integrates content from over 600 data sources, creating a diverse chemical space that supports robust model generalization [23] [24].

ChEMBL distinguishes itself through expert manual curation, focusing on bioactive molecules with confirmed drug-like properties. This curation ensures high-quality data labels—a critical factor for supervised pre-training and fine-tuning phases where data quality significantly impacts model performance [25]. Recent releases have incorporated specialized annotations including Natural Product likeness scores, Chemical Probe flags, and action type classifications for approximately 270,000 bioactivity measurements, providing rich metadata for multi-task learning approaches [25].

ZINC specializes in "tangible chemical space"—molecules that are commercially available or readily synthesizable—making it uniquely valuable for models whose outputs require experimental validation. The ZINC-22 release provides pre-computed molecular properties including conformations, partial atomic charges, cLogP values, and solvation energies that are "crucial for molecule docking" and other structure-based applications [26]. The database's organization enables rapid lookup operations, addressing previous scalability limitations in virtual screening workflows.

CEPDB occupies a specialized niche in organic electronics, particularly molecular semiconductors for organic photovoltaics (OPV). Its value proposition lies in the massive volume of first-principles quantum chemistry calculations, including empirically calibrated and statistically post-processed DFT calculations that provide high-quality electronic property predictions [29] [28]. This dataset supports model training for predicting quantum mechanical properties without the computational expense of ab initio calculations during inference.

Table 2: Domain specialization and application-specific strengths of each database.

| Database | Chemical Space Coverage | Primary Application Domains | Data Quality & Curation | Update Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubChem | Broad: drug-like, lead-like, & diverse chemotypes | • Drug discovery• Chemical biology• Cheminformatics• Polypharmacology | • Automated standardization• Multi-source integration• Variable quality by source | Continuous (multiple data sources) |

| ChEMBL | Focused: bioactive, drug-like compounds | • Target validation• Lead optimization• Mechanism of action studies• Drug repurposing | • Manual expert curation• Uniform quality standards• Experimental data focus | Regular quarterly releases |

| ZINC | Purchasable: commercially accessible compounds | • Virtual screening• Ligand discovery• Analog searching• Structure-based design | • Vendor-supplied availability• Computational property prediction• Automated 3D generation | Regular updates with new vendors |

| CEPDB | Specialized: organic electronic materials | • Organic photovoltaics• Electronic materials design• Charge transport prediction• Materials informatics | • High-throughput DFT data• Empirical calibration• Experimental validation subsets | Periodic releases with new calculations |

Database Integration for Foundation Model Pre-training

Strategic Database Selection and Combined Utilization

Effective pre-training of foundation models for materials discovery requires strategic selection and combination of database resources based on the target application domain. For drug discovery applications, a combined approach leveraging PubChem's breadth and ChEMBL's curated bioactivity data provides both extensive chemical coverage and high-quality activity annotations. The 3.4 million compounds with bioactivity data in PubChem (3.5% of its total compounds), including high-throughput screening results with both active and inactive measurements, complements ChEMBL's literature-extracted bioactivity data focused primarily on active compounds [23] [24]. This combination addresses the common challenge of negative data scarcity in biochemical annotation.

For virtual screening and ligand discovery, ZINC's purchasable compounds with ready-to-dock 3D formats provide immediate practical utility. The database's growth to billions of molecules has not compromised diversity, with a log increase in Bemis-Murcko scaffolds for every two-log unit increase in database size, ensuring continued structural novelty [26]. Integration with property prediction models trained on CEPDB's quantum chemical data can further enhance screening by enriching ZINC compounds with predicted electronic properties.

For organic electronics and energy materials, CEPDB serves as the primary resource, with potential augmentation from PubChem's synthetic accessibility information. The CEPDB's data on electronic and optical properties—including HOMO-LUMO energies, band gaps, and absorption spectra—provides essential features for predicting materials performance in specific applications [29] [28]. The planned expansion of experimental data in CEPDB will further enhance its utility for supervised fine-tuning.

Data Extraction and Pre-processing Workflows

Robust data extraction and pre-processing pipelines are essential for transforming raw database content into training-ready datasets. The foundational step involves chemical structure standardization to ensure consistent molecular representation across sources. PubChem's structure standardization pipeline provides a validated approach, resolving tautomeric forms, neutralizing charges, and removing counterions to create canonical representations [24].

For multi-modal learning, effective data extraction must transcend simple text-based approaches. Modern foundation models benefit from integrating multiple data modalities, including:

- Textual data from scientific literature and patent documents

- Structured tables of experimental measurements

- Molecular representations (SMILES, SELFIES, graphs, 3D coordinates)

- Spectral data and other characterization results

Advanced extraction techniques include named entity recognition (NER) for material identification [2], computer vision approaches like Vision Transformers for molecular structure identification from images [2], and specialized algorithms such as Plot2Spectra for extracting data points from spectroscopy plots [2]. These approaches address the challenge that significant materials information resides in non-textual formats such as tables, images, and molecular structures embedded in documents.

Diagram 1: Data extraction and pre-processing workflow for foundation model training, showing multi-modal data integration from scientific databases.

Molecular Representation Strategies

The choice of molecular representation significantly impacts foundation model performance and generalization. The current landscape is dominated by 2D representations including SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) and SELFIES (Self-Referencing Embedded Strings), primarily due to the extensive availability of 2D data in sources like ZINC and ChEMBL which offer datasets approaching ~10^9 molecules [2]. However, this approach omits critical 3D conformational information that directly influences molecular properties and biological activity.

Graph-based representations that treat atoms as nodes and bonds as edges provide an alternative that naturally captures molecular topology. These representations align well with graph neural network architectures that have shown strong performance in property prediction tasks. For inorganic solids and crystalline materials, 3D structure representations using graph-based or primitive cell feature representations are more common, leveraging the spatial periodicity of these materials [2].

The limited availability of large-scale 3D molecular datasets remains a significant challenge, though databases like ZINC (providing ready-to-dock 3D formats for over 230 million compounds) [26] and CEPDB (containing 22 million geometries) [28] are helping to bridge this gap. Emerging approaches include using generative models to predict likely 3D conformations from 2D structures, creating hybrid representation learning frameworks that leverage both abundant 2D data and limited 3D data.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation Guidelines

Foundation Model Architecture Selection

Selecting appropriate model architectures forms the cornerstone of effective pre-training strategies. The transformer architecture, originally developed for natural language processing, has demonstrated remarkable success in molecular representation learning when adapted to chemical structures. Two primary architectural paradigms have emerged:

Encoder-only models follow the BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) architecture and excel at understanding and representing input data for property prediction tasks [2]. These models are typically pre-trained using masked language modeling objectives, where random tokens in the input sequence (e.g., atoms in a molecular graph or characters in a SMILES string) are masked and the model learns to predict them based on context. For molecular data, this approach enables learning rich, context-aware representations that capture chemical rules and structural patterns.

Decoder-only models focus on generative tasks, predicting sequences token-by-token based on given input and previously generated tokens [2]. These models, following the GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) architecture, are particularly suited for de novo molecular design and optimization. When conditioned on specific property constraints, decoder-only models can generate novel molecular structures with desired characteristics, enabling inverse design approaches.

Recent trends indicate growing interest in encoder-decoder architectures that combine the representational power of encoder models with the generative capabilities of decoder models. These architectures support complex tasks such as reaction prediction, molecular optimization, and cross-modal translation between different molecular representations.

Pre-training Methodology and Technical Implementation

Successful pre-training requires careful methodology encompassing data sampling, objective selection, and optimization strategy. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for foundation model pre-training on chemical databases:

Data Sampling and Curation:

- Multi-database integration: Combine structures from PubChem, ZINC, and ChEMBL to ensure diverse chemical coverage, while applying standardization to maintain consistency

- Property stratification: Sample compounds to ensure adequate representation of different property ranges (e.g., molecular weight, lipophilicity, bioactivity)

- Scaffold-based splitting: Partition data based on molecular scaffolds to assess model performance on structurally novel compounds during validation

Pre-training Objectives:

- Masked language modeling: Mask portions of input sequences (15-20%) and train the model to reconstruct the original tokens

- Multi-modal alignment: For databases with associated property data (CEPDB electronic properties, ChEMBL bioactivities), incorporate property prediction as an auxiliary task

- Contrastive learning: Maximize agreement between different representations of the same molecule (e.g., SMILES, graph, 3D conformer) while minimizing agreement between different molecules

Implementation Details:

- Model scale: Base models typically range from 12-24 transformer layers with hidden dimensions of 768-1024

- Optimization: Use AdamW optimizer with learning rate warmup followed by cosine decay

- Regularization: Apply attention dropout (0.1) and hidden dropout (0.3) to prevent overfitting

- Batch size: Utilize large batch sizes (1024-4096 sequences) for stable contrastive learning

Diagram 2: Foundation model pre-training and fine-tuning workflow, showing architecture selection and training objectives.

Table 3: Essential research reagents, tools, and resources for foundation model development in materials discovery.

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function & Application | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Databases | PubChem, ChEMBL, ZINC, CEPDB | • Source data for pre-training• Chemical space analysis• Property benchmarking | • Web interfaces• REST APIs• Bulk downloads |

| Representation Libraries | RDKit, DeepChem, OEChem | • Molecular standardization• Feature generation• Molecular representation | • Python packages• Open-source |

| Model Architectures | Transformer variants, GNN frameworks | • Base model implementation• Custom architecture development | • PyTorch/TensorFlow• Hugging Face |

| Pre-training Infrastructure | NVIDIA GPUs, Google TPUs, Cloud computing | • Distributed training• Large-scale experimentation | • Cloud providers (AWS, GCP)• HPC clusters |

| Benchmarking Suites | MoleculeNet, OGB (Open Graph Benchmark) | • Performance evaluation• Model comparison• Transfer learning assessment | • Open-source packages• Standardized datasets |

| Specialized Toolkits | PUG-REST (PubChem), ChEMBL web services, ZINC API | • Automated data retrieval• Real-time database querying• Pipeline integration | • RESTful APIs• Programmatic access |

The strategic integration of PubChem, ZINC, ChEMBL, and CEPDB provides a comprehensive foundation for pre-training models capable of accelerating discovery across drug development and materials science. Each database contributes unique strengths: PubChem offers unprecedented scale and diversity, ChEMBL provides high-quality curated bioactivity data, ZINC delivers commercially accessible compounds with ready-to-dock formats, and CEPDB enables specialized prediction of electronic and optical properties. As foundation models continue to evolve, several emerging trends will shape their development: increased emphasis on 3D structural information, growth of multi-modal learning approaches that integrate textual and structural data, and development of more sophisticated pre-training objectives that better capture chemical intuition. The ongoing expansion of these databases—with ChEMBL increasingly incorporating deposited screening data, ZINC growing toward trillion-molecule scales, and CEPDB adding experimental validation—will further enhance their utility for training next-generation AI systems. By leveraging these public resources through the methodologies outlined in this guide, researchers can develop powerful foundation models that transform the pace and efficiency of molecular and materials innovation.

From Prediction to Generation: Methodologies and Real-World Applications

The field of materials discovery is undergoing a paradigm shift with the advent of foundation models—large-scale machine learning models pre-trained on extensive datasets that can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks [2]. Of these, the encoder-only and decoder-only transformer architectures have emerged as particularly influential. Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) and Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) represent two fundamentally different approaches to language modeling that can be repurposed for scientific discovery [30] [31]. These models can process structured textual representations of materials, such as Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) strings or SELFIES, to predict properties, plan syntheses, and generate novel molecular structures [2]. This technical guide examines the architectural nuances, training methodologies, and practical applications of these models within organic materials discovery research.

Architectural Fundamentals: Core Components and Divergence

The Transformer Backbone

Both BERT and GPT architectures derive from the original transformer architecture introduced in the "Attention Is All You Need" paper, which relies on self-attention mechanisms rather than recurrence or convolution to process sequential data [32] [30]. The self-attention mechanism allows the model to weigh the importance of different words in a sequence when encoding a particular word, enabling it to capture contextual relationships regardless of distance [32] [33]. The key innovation was the ability to parallelize sequence processing more effectively than previous recurrent or convolutional approaches, dramatically accelerating training on large datasets [34].

The original transformer contained both an encoder and decoder component [30]. The encoder maps an input sequence to a sequence of continuous representations, while the decoder generates an output sequence one element at a time using previously generated elements as additional input [32]. This architectural bifurcation established the foundation for the specialized encoder-only and decoder-only models that would follow.

BERT: Encoder-Only Architecture

BERT implements a pure encoder architecture, discarding the transformer's decoder component [35] [30]. Its design centers on bidirectional context understanding, meaning it processes all tokens in a sequence simultaneously rather than sequentially [34]. BERT's architecture consists of four main components:

- Tokenizer: Converts text into tokens using WordPiece sub-word tokenization with a 30,000 token vocabulary [35]

- Embedding Layer: Combines token, position, and segment embeddings to represent each token [35]

- Encoder Stack: Multiple transformer encoder blocks with self-attention but no causal masking [35]

- Task Head: Converts final representations into predictions; often replaced for downstream tasks [35]

The embedding process incorporates three distinct information types: token type embeddings (standard word embeddings), position embeddings (absolute position using sinusoidal functions), and segment type embeddings (distinguishing between first and second text segments) [35]. These are summed together and normalized before passing through the encoder stack.