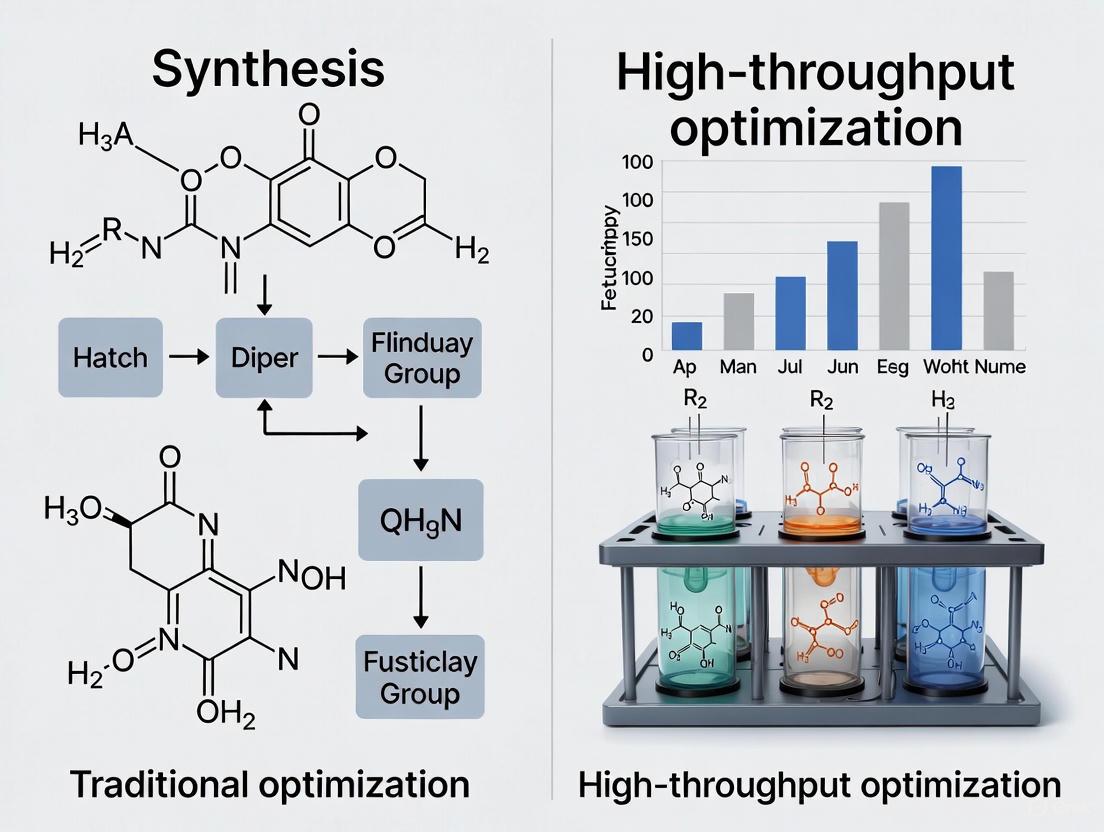

From Serendipity to Systems: A Comparative Analysis of Traditional and High-Throughput Optimization Methods in Modern Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between traditional drug discovery methods and modern high-throughput optimization techniques, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

From Serendipity to Systems: A Comparative Analysis of Traditional and High-Throughput Optimization Methods in Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between traditional drug discovery methods and modern high-throughput optimization techniques, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of both approaches, detailing the methodological shifts brought by automation, robotics, and artificial intelligence. The content addresses common challenges in high-throughput screening (HTS), including data analysis and false positives, while offering optimization strategies. Through a rigorous validation and comparative analysis, it evaluates the performance, cost-effectiveness, and success rates of each paradigm, concluding with a synthesis of key takeaways and future implications for biomedical research and clinical development.

The Evolution of Drug Discovery: From Accidental Finds to Automated Systems

Traditional drug design represents the foundational approach to pharmaceutical discovery that relied heavily on empirical methods rather than targeted molecular design. Before the advent of modern computational and high-throughput methods, drug discovery was primarily guided by two core principles: random screening of compound libraries and the recognition of serendipitous discoveries during research [1] [2]. This approach dominated pharmaceutical research for much of the 20th century and was responsible for identifying many therapeutic agents that remain in clinical use today.

Random screening involves the systematic experimental testing of large collections of natural or synthetic compounds for desirable biological activity, without necessarily having prior knowledge of their mechanism of action [2]. Serendipity, derived from the Persian fairy tale "The Three Princes of Serendip," refers to the faculty of making fortunate discoveries accidentally while searching for something else [3]. In scientific terms, serendipity implies "the finding of one thing while looking for something else" [3], though as Louis Pasteur famously observed, "chance favors the prepared mind" [3], emphasizing that recognizing the value of accidental discoveries requires considerable scientific expertise.

This review examines the principles, methodologies, and legacy of these traditional approaches within the contemporary context of drug discovery, which is increasingly dominated by high-throughput optimization methods and artificial intelligence-driven platforms [4] [5].

Core Principles and Historical Significance

The Conceptual Framework of Traditional Drug Discovery

Traditional drug discovery operated on a fundamentally different paradigm than modern structured approaches. The process typically began with identifying a therapeutic need, followed by the collection and screening of available compounds through phenotypic assays rather than target-based approaches [1] [2]. The journey from initial screening to marketed drug was lengthy and resource-intensive, often requiring 12-15 years from initial testing to regulatory approval [2].

The traditional drug discovery pipeline can be visualized through the following workflow:

This process was characterized by high attrition rates, with approximately 10,000 synthesized and tested compounds yielding only one approved drug [1]. The main reasons for failure included lack of efficacy when moving from animal models to humans and unfavorable pharmacokinetic properties [1].

The Role of Serendipity in Landmark Discoveries

Serendipity has played a crucial role in many landmark drug discoveries that transformed medical practice. Historical analysis reveals that serendipitous discoveries generally fall into three distinct categories:

Table: Categories of Serendipitous Drug Discoveries

| Category | Definition | Prototypical Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Finding One Thing While Looking for Another | Discovery of unexpected therapeutic effect while researching different indications | Penicillin (antibacterial), Aniline Purple (dye), LSD (psychoactive), Meprobamate (tranquilizer), Chlorpromazine (antipsychotic), Imipramine (antidepressant) [3] |

| False Rationale Leading to Correct Results | Incorrect hypothesis about mechanism nevertheless yields therapeutically beneficial outcomes | Potassium Bromide (sedative), Chloral Hydrate (hypnotic), Lithium (mood stabilizer) [3] |

| Discovery of Unexpected Indications | Drugs developed for one condition found effective for different therapeutic applications | Iproniazid (antidepressant), Sildenafil (erectile dysfunction) [3] |

The story of penicillin discovery by Alexander Fleming exemplifies the first category, where contamination of bacterial plates led to the observation of antibacterial activity [1]. Similarly, chlorpromazine was initially investigated for anesthetic properties before its transformative antipsychotic effects were recognized [3]. These discoveries highlight how observant researchers capitalized on unexpected findings to revolutionize therapeutic areas.

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Random Screening Workflows and Techniques

Traditional random screening methodologies formed the backbone of pharmaceutical discovery for decades. The process involved sequential phases with distinct experimental goals:

The experimental protocols for traditional random screening involved several critical stages:

Compound Library Assembly: Early libraries consisted of thousands to hundreds of thousands of compounds sourced from natural product extracts, synthetic chemical collections, or existing compounds developed for other purposes [2]. These libraries were orders of magnitude smaller than modern screening collections, which can encompass millions of compounds [1].

Primary Screening: Initial assays typically used cell-based or biochemical in vitro systems to identify "hits" - compounds producing a desired biological response [2]. These assays measured phenotypic changes, enzyme inhibition, or receptor binding without the sophisticated target validation common today.

Hit Validation: Promising hits underwent confirmation testing to exclude false positives and establish preliminary dose-response relationships [2]. This included counterscreening against related targets to assess selectivity.

Lead Declaration: Compounds with confirmed activity and acceptable initial properties were designated "leads" and prioritized for further optimization [2].

Chemical Optimization: Medicinal chemists performed systematic structural modifications to improve potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties through iterative synthesis and testing cycles [1].

Preclinical Profiling: Optimized leads underwent extensive safety and pharmacokinetic evaluation in animal models before candidate selection for clinical development [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Traditional drug discovery relied on a core set of experimental tools and reagents that formed the essential toolkit for researchers:

Table: Essential Research Reagents in Traditional Drug Discovery

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Protocols |

|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | Collections of natural extracts, synthetic molecules, or known compounds for screening; typically stored in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solutions [2] |

| Biochemical Assay Kits | Enzyme substrates, cofactors, and buffers for in vitro activity screening against purified molecular targets [2] |

| Cell Culture Systems | Immortalized cell lines for phenotypic screening and preliminary toxicity assessment [2] |

| Radioactive Ligands | Radiolabeled compounds (e.g., ³H- or ¹²⁵I-labeled) for receptor binding studies in target characterization and competition assays [2] |

| Animal Models | In vivo systems (typically rodents) for efficacy and safety pharmacology assessment before human trials [1] |

| Chromatography Systems | High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) for compound purity analysis and metabolite identification [1] |

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. Modern Approaches

Performance Metrics and Outcomes

When comparing traditional drug discovery approaches with contemporary high-throughput methods, significant differences emerge across multiple performance dimensions:

Table: Performance Comparison of Drug Discovery Approaches

| Parameter | Traditional Methods | Modern High-Throughput & AI Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Screening Throughput | Low to moderate (hundreds to thousands of compounds) [2] | Very high (millions of compounds virtually or experimentally) [1] [6] |

| Timeline (Hit to Lead) | Months to years [2] | Weeks to months (e.g., 21 days for AI-designed DDR1 kinase inhibitors) [5] |

| Attrition Rate | High (~90% failure in clinical development) [1] | Improved through better early prediction (e.g., reduced pharmacokinetic failures from 39% to ~1%) [1] |

| Primary Screening Cost | High (physical screening of large compound libraries) [1] | Lower for virtual screening, higher for experimental HTS but with better hit rates [6] |

| Chemical Space Exploration | Limited to available compounds [2] | Vast expansion through generative AI (e.g., 52 trillion molecules to 12 specific antivirals) [4] |

| Hit Rate | Low (0.001-0.01%) [1] | Significantly improved (e.g., 100% hit rate in GALILEO antiviral discovery) [4] |

| Serendipity Factor | High (multiple landmark discoveries) [3] | Lower, though emerging AI approaches aim to recapture systematic serendipity [7] |

The data reveals that modern approaches substantially outperform traditional methods in efficiency and throughput. However, traditional methods demonstrated a remarkable capacity for serendipitous discovery, yielding multiple therapeutic breakthroughs that might have been missed by more targeted approaches.

Strengths and Limitations in Contemporary Context

Both traditional and modern drug discovery paradigms present distinctive advantages and limitations:

Strengths of Traditional Approaches:

- Unbiased Discovery: Open-ended screening allowed identification of novel mechanisms without predefined hypotheses [2]

- Proven Success: Delivered multiple first-in-class therapeutics across diverse disease areas [3]

- Phenotypic Relevance: Cell-based and in vivo screening ensured biological relevance in complex systems [2]

Limitations of Traditional Approaches:

- Low Efficiency: Resource-intensive with high failure rates [1]

- Limited Scalability: Physical constraints on library size and screening capacity [2]

- Mechanistic Uncertainty: Often proceeded without clear understanding of molecular targets [1]

Modern High-Throughput and AI Advantages:

- Unprecedented Scale: Ability to screen billions of compounds virtually [4] [6]

- Rational Design: Target-based approaches enable precise chemical optimization [1] [6]

- Reduced Timelines: AI-accelerated discovery (e.g., 12-18 months vs. 4-6 years) [5] [8]

Case Studies: Exemplars of Traditional Discovery

The Serendipity Spectrum in Practice

Historical case studies illustrate the varied manifestations of serendipity in pharmaceutical research:

Lithium in Mood Disorders: The discovery of lithium's therapeutic effects represents serendipity through incorrect rationale. In the 19th century, William Hammond and Carl Lange independently used lithium to treat mood disorders based on the false "uric acid diathesis" theory that mental illness resulted from accumulated urea [3]. Despite the erroneous rationale, their empirical observations were correct, and lithium was rediscovered in the 1940s by John Cade, eventually becoming a mainstay treatment for bipolar disorder [3].

Sildenafil (Viagra): This example illustrates discovery of unexpected indications. Initially developed as an antihypertensive agent, sildenafil was found to produce unexpected side effects that led to its repurposing for erectile dysfunction, eventually becoming one of the best-selling drugs ever and establishing an entirely new pharmacological class [1].

Penicillin: The classic example of finding one thing while looking for another, Alexander Fleming's 1928 observation of antibacterial activity from Penicillium mold contamination fundamentally transformed medicine and initiated the antibiotic era [1] [3].

Random Screening Success Stories

Prontosil: The first sulphonamide antibiotic was discovered through systematic random screening of colorants for antibacterial activity [1]. This discovery validated the screening approach and launched the antimicrobial revolution.

Paclitaxel: This novel anti-tumor agent was identified through high-throughput screening of natural products, demonstrating how random screening could yield structurally unique therapeutics with novel mechanisms of action [1].

The Modern Legacy: Integration with Contemporary Approaches

Systematic Serendipity in the AI Era

While traditional random screening has been largely superseded by targeted approaches, the principle of serendipity is experiencing a renaissance through artificial intelligence. Modern research aims to recapture systematic serendipity through computational methods [7]. The SerenQA framework represents one such approach, using knowledge graphs and large language models to identify "surprising" connections for drug repurposing by quantifying serendipity through relevance, novelty, and surprise metrics [7].

Emerging hybrid models combine AI-driven prediction with experimental validation, creating a new paradigm that leverages the scale of computational approaches while maintaining the discovery potential of traditional methods [4] [5]. For instance, quantum-enhanced drug discovery pipelines have successfully identified novel molecules for challenging oncology targets like KRAS-G12D by screening 100 million molecules and synthesizing only the most promising candidates [4].

Traditional drug design based on random screening and serendipity established foundational principles that continue to inform modern discovery approaches. While contemporary high-throughput and AI methods have dramatically improved the efficiency and success rates of drug discovery, the legacy of traditional approaches remains relevant. The prepared mind that recognizes unexpected discoveries, the value of phenotypic screening in complex systems, and the importance of exploring diverse chemical space represent enduring principles that continue to guide pharmaceutical innovation.

The future of drug discovery appears to lie in hybrid approaches that leverage the scale and predictive power of computational methods while creating systematic opportunities for serendipitous discovery, ultimately combining the best of both paradigms to address unmet medical needs more effectively.

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) represents a fundamental transformation in how scientific experimentation is conducted, particularly in drug discovery and development. This approach has emerged as an indispensable solution to the challenges of exploring vast experimental spaces in complex biological and chemical systems. By integrating three core principles—automation, miniaturization, and parallel processing—HTS enables the rapid assessment of thousands to millions of compounds against biological targets, dramatically accelerating the pace of scientific discovery [9] [10].

The transition from traditional manual methods to HTS signifies more than just a technical improvement; it constitutes a complete paradigm shift in research methodology. Where traditional optimization has historically relied on manual experimentation guided by human intuition and one-variable-at-a-time approaches, HTS introduces a systematic, data-driven framework that synchronously optimizes multiple reaction variables [11]. This shift has been particularly critical in pharmaceutical research, where the need to efficiently process enormous compound libraries against increasingly complex targets has made HTS an operational imperative [9] [10].

Core Principles and Operational Framework

The Triad of HTS Efficiency

The transformative power of HTS stems from the synergistic integration of three fundamental principles:

Automation: Robotic systems perform precise, repetitive laboratory procedures without human intervention, enabling continuous 24/7 operation and eliminating inter-operator variability. Automated liquid handlers can dispense nanoliter aliquots with exceptional accuracy across multi-well plates, while integrated robotic arms move plates between functional modules like incubators and readers [10].

Miniaturization: Assays are conducted in dramatically reduced volumes using standardized microplate formats (96-, 384-, and 1536-well plates). This conservation of expensive reagents and proprietary compounds significantly reduces operational costs while maintaining experimental integrity [9] [10].

Parallel Processing: Unlike traditional sequential experimentation, HTS tests thousands of compounds simultaneously against biological targets, collapsing hit identification timelines from months to days and enabling comprehensive exploration of chemical space [10].

Quantitative Comparison: Traditional vs. HTS Methods

Table 1: Direct comparison between traditional optimization and high-throughput screening approaches

| Parameter | Traditional Methods | High-Throughput Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Throughput | Few to dozens of samples per day | 10,000–100,000+ compounds per day [9] |

| Reagent Consumption | High (milliliter range) | Minimal (nanoliter to microliter range) [10] |

| Process Variability | Significant inter-operator and inter-batch variation | Highly standardized with minimal variability [10] |

| Data Generation | Limited, often sequential data acquisition | Massive parallel data generation requiring specialized informatics [9] [10] |

| Experimental Design | One-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) approach [11] | Multivariate synchronous optimization [11] |

| Resource Requirements | Lower initial investment | High infrastructure costs and specialized expertise needed [9] |

Workflow Integration and Automation Architecture

Table 2: Key functional modules in an integrated HTS robotics platform

| Module Type | Primary Function | Critical Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Handler | Precise fluid dispensing and aspiration | Sub-microliter accuracy; low dead volume [10] |

| Plate Incubator | Temperature and atmospheric control | Uniform heating across microplates [10] |

| Microplate Reader | Signal detection (fluorescence, luminescence) | High sensitivity and rapid data acquisition [10] |

| Plate Washer | Automated washing cycles | Minimal residual volume and cross-contamination control [10] |

| Robotic Arm | Microplate movement between modules | High precision and reliability for continuous operation [10] |

The following workflow diagram illustrates how these modules integrate to form a complete HTS system:

HTS Automated Workflow Integration - This diagram illustrates the seamless integration of robotic modules in a complete HTS system, from compound library preparation through data analysis.

Experimental Validation and Performance Metrics

Assay Quality Validation Protocols

The transition to HTS requires rigorous validation to ensure data quality and reproducibility. Key experimental protocols include:

Z-Factor Calculation: The Z-factor is a critical statistical parameter used to assess assay quality and robustness. It is calculated using the formula: Z-factor = 1 - (3σ₊ + 3σ₋) / |μ₊ - μ₋|, where σ₊ and σ₋ are the standard deviations of positive and negative controls, and μ₊ and μ₋ are their respective means. A Z-factor ≥ 0.5 indicates an excellent assay suitable for HTS implementation [10].

Signal-to-Background Ratio: This metric evaluates assay window size by comparing the signal intensity between positive controls and background measurements. Optimal thresholds vary by assay type but typically exceed 3:1 for robust screening [10].

Coefficient of Variation (CV): Precision across replicates is monitored using CV, calculated as (standard deviation/mean) × 100%. CV values below 10-15% indicate acceptable reproducibility for HTS applications [10].

Comparative Performance Data

Table 3: Experimental performance comparison across screening methodologies

| Performance Metric | Traditional Methods | Standard HTS | Ultra-HTS (uHTS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Throughput | 10-100 compounds [9] | 10,000–100,000 compounds [9] | >300,000 compounds [9] |

| Assay Volume | 1 mL – 100 μL | 100 μL – 10 μL | 2 μL – 1 μL [9] |

| Hit Rate Accuracy | Moderate (subject to human error) | High (automated standardization) [10] | Very High (advanced detection) [9] |

| False Positive Rate | Variable | Managed via informatics triage [9] | Controlled via advanced sensors [9] |

| Data Generation Rate | Manual recording | Automated capture (thousands of points/plate) [10] | Continuous monitoring (millions of points/day) [9] |

Case Study: uHTS Implementation

Swingle et al. demonstrated the power of uHTS in a campaign testing over 315,000 small molecule compounds daily against protein phosphatase targets (PP1C and PP5C) using a miniaturized 1536-well plate format. This approach required volumes of just 1-2 μL and leveraged advanced fluid handling technologies to overcome previous limitations in ultra-high-throughput applications [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential HTS Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key reagents and materials for high-throughput screening implementations

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Based Assay Kits | Deliver physiologically relevant data through direct assessment of compound effects in biological systems [12] | Enable functional analysis for safety and efficacy profiling; often use live-cell imaging and fluorescence [12] |

| Specialized Reagents & Kits | Assay preparation and execution with ensured reproducibility [12] | Formulations optimized for specific platforms; increasing adoption of ready-to-use kits reduces setup time [12] |

| Microplates (96-1536 well) | Miniaturized reaction vessels for parallel processing [10] | Standardized formats enable automation compatibility; 1536-well plates essential for uHTS [9] [10] |

| Enzymatic Assay Components | Target-based screening against specific biological targets [9] | Include peptide substrates with suitable leaving groups for quantification; HDAC inhibitors are a common application [9] |

| Detection Reagents | Signal generation for readout systems | Fluorescence-based methods most common due to sensitivity and adaptability to HTS formats [9] |

Advanced Applications and Implementation Considerations

Data Management and Computational Integration

The massive data output from HTS necessitates robust informatics infrastructure. A typical HTS run generates thousands of raw data points per plate, including intensity values, spectral information, and kinetic curves [10]. Comprehensive Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) perform essential tasks including compound tracking, plate registration, and application of correction algorithms [10].

Advanced computational approaches have been developed to address the challenge of false positives in HTS data, including:

- Machine Learning Models: Trained on historical HTS data to identify patterns associated with false positives [9]

- Pan-Assay Interferent Substructure Filters: Expert rule-based approaches to flag compounds with problematic chemical motifs [9]

- Statistical QC Methods: Automated outlier detection to address both random and systematic HTS variability [9]

Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Despite its advantages, HTS implementation faces significant technical barriers:

High Infrastructure Costs: Establishing HTS facilities requires substantial investment in automation, specialized equipment, and maintenance [9]. This can be particularly challenging for smaller research institutes.

Integration Complexity: Connecting legacy instrumentation with modern robotics often requires custom middleware development due to proprietary communication protocols [10].

Specialized Personnel Requirements: The operational role shifts from manual execution to system validation, maintenance, and complex data analysis, requiring advanced training [10].

The following diagram illustrates the data management and analysis pipeline required for effective HTS operations:

HTS Data Analysis Pipeline - This visualization shows the sequential stages of HTS data processing, from raw data acquisition through confirmed hit identification, including key quality control steps.

The integration of automation, miniaturization, and parallel processing in HTS represents a fundamental advancement in research methodology that transcends mere technical improvement. The experimental data and comparative analysis presented demonstrate that HTS consistently outperforms traditional methods across critical parameters: throughput (100-10,000x improvement), reagent conservation (10-100x reduction), and standardization (significantly reduced variability) [9] [10].

For research organizations evaluating implementation, the decision involves balancing substantial upfront investment and technical complexity against dramatically accelerated discovery timelines and enhanced data quality [9] [12]. The continuing evolution of HTS technologies—particularly the integration of artificial intelligence for data analysis and the emergence of ultra-high-throughput screening capable of processing millions of compounds daily—ensures that this methodology will remain indispensable for drug discovery and development pipelines [9] [12].

As the field progresses, the convergence of HTS with advanced computational approaches like machine learning and active optimization creates new opportunities for knowledge discovery [11] [13]. This synergy between high-throughput experimental generation and intelligent data analysis represents the next frontier in research optimization, potentially transforming not only how we screen compounds but how we formulate scientific hypotheses themselves.

The 1990s marked a revolutionary decade for drug discovery, defined by the pharmaceutical industry's widespread adoption of High-Throughput Screening (HTS). This period saw a fundamental shift from slow, manual, hypothesis-driven methods to automated, systematic processes capable of empirically testing hundreds of thousands of compounds. Driven by pressures to accelerate development and reduce costs, this transformation was fueled by breakthroughs in automation, assay technology, and miniaturization, increasing screening capabilities by two to three orders of magnitude and establishing HTS as a central pillar of modern pharmaceutical research [14] [15].

The Driving Forces for Industrial Adoption

The adoption of HTS was not a mere technological upgrade but a strategic response to critical challenges within the drug discovery ecosystem.

- Mounting Economic and Temporal Pressures: The pharmaceutical industry faced increasing pressure to reduce the immense time and financial burden associated with bringing a new drug to market. HTS emerged as a strategic solution to this challenge, promising to streamline the early discovery phase and improve the efficiency of Research and Development pipelines [14].

- The Shift from Subset to Full-File Screening: A core tenet behind this empirical approach was the belief that screening an entire corporate compound file was more effective than testing subsets selected by human intuition. This comprehensive method aimed to uncover novel, unexpected structure-activity relationships that might otherwise be missed [15].

- The Inadequacy of Traditional Methods: Traditional methods were inherently slow, labor-intensive, and struggled to keep pace with the growing demands of modern drug development. Before HTS, screening was a manual process where a single researcher might test only a few hundred compounds per week, with projects often taking years to screen a small fraction of the available compound library [14] [15].

Core Technological Breakthroughs and Their Impact

The paradigm shift to HTS was enabled by concurrent advancements across several technological domains, which together created a new, integrated screening infrastructure.

Automation and Robotics

The introduction of robotic systems and automated workstations was a defining feature of 1990s HTS. These systems automated repetitive tasks such as pipetting, sample preparation, and liquid handling. They were deployed either on integrated robotic platforms or as standalone workstations operated by human technicians, significantly increasing throughput while reducing human error and variability [14] [15].

Assay Technology Revolution

The development of "HTS-friendly" assay technologies was pivotal. New techniques like Scintillation Proximity Assay (SPA), Homogeneous Time-Resolved Fluorescence (HTRF), and Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy (FCS) obviated the need for complex, multi-step protocols involving separation steps like filtration or centrifugation. These homogeneous (or "mix-and-read") assays greatly accelerated throughput and improved data quality, making large-scale screening campaigns practically feasible [15].

Miniaturization and Microplate Formats

The adoption and evolution of the microplate were crucial for achieving high throughput. The industry transitioned from the 96-well format to 384-well plates, which represented a pragmatic balance between ease of use and increased throughput. This period also saw early investigation into 1536-well plates and other ultra-miniaturization strategies, which reduced reagent consumption and operational costs [14] [15].

The Data Management Foundation

The widespread deployment of affordable, powerful computing was the silent enabler of the HTS revolution. It allowed for the seamless electronic integration of HTS components, enabling the management of data capture, compound information, and quality control processes that were previously handled through manual, paper-based entry [15].

The table below summarizes the transformative impact of these technological breakthroughs.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Screening Capabilities: Pre-HTS vs. 1990s HTS

| Screening Feature | Pre-HTS (c. 1990) | 1990s HTS/uHTS | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput Rate | A few hundred compounds/week [15] | 10,000 - 100,000 compounds/day [15] | 2-3 orders of magnitude increase [15] |

| Typical Project Scale | 5,000 - 20,000 compounds over years [15] | 100,000 - 500,000+ compounds per campaign [15] | Shift from subset to full-file screening [15] |

| Automation Level | Manual processes; individual compound testing [14] | Integrated robotic systems & automated workstations [14] [15] | Reduced human error; enabled massive scale [14] |

| Primary Assay Formats | Laborious, multi-step protocols with separation steps [15] | Homogeneous "mix-and-read" assays (e.g., SPA, HTRF) [15] | Faster, higher-quality data; simpler automation [15] |

| Data Management | Manual collation and entry of data [15] | Electronic, integrated data capture and QA/QC [15] | Seamless data handling for millions of results [15] |

Experimental Protocol: A Typical 1990s uHTS Campaign

The workflow of a state-of-the-art ultra-High-Throughput Screening (uHTS) campaign at the end of the 1990s involved a highly coordinated, multi-stage process. The following diagram outlines the core operational workflow and the technological integrations that made it possible.

Detailed Methodological Steps

- Assay Development and Adaptation: A biochemical or cell-based assay protocol was first developed and then rigorously adapted for automation. This involved defining key parameters, sensitivities, and tolerances to ensure robustness and reproducibility on the HTS hardware [15].

- Compound Library Reformating: The corporate compound collection (typically 100,000 to over 500,000 compounds) was managed in centralized repositories. For each screen, compounds were reformatted from master stock plates into assay-ready microplates [15].

- Automated Assay Execution: Using integrated robotic systems or workstations, the process involved:

- Liquid Handling: Precise, non-contact or contact dispensing of nanoliter to microliter volumes of compounds, buffers, and biochemical reagents (enzymes, substrates) into 96- or 384-well microplates [14] [15].

- Incubation: Plates were incubated under controlled conditions (temperature, CO₂) for a specified period to allow for biochemical reactions or cellular responses.

- Signal Detection: Plate readers equipped with appropriate detectors (e.g., for fluorescence, luminescence, or radioactivity) captured the assay signal from each well [15].

- Data Processing and Hit Identification: The raw data from plate readers was automatically captured by a centralized data management system. Statistical methods were applied to distinguish biologically active compounds (hits) from assay variability, typically by comparing compound activity to plate-based positive and negative controls [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The successful execution of a 1990s HTS campaign relied on a suite of essential materials and reagents.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 1990s HTS

| Item | Function in HTS |

|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | Diverse collections of 100,000 to 1+ million small molecules, representing the corporate intellectual property file, which were screened for biological activity [15]. |

| "HTS-Friendly" Assay Kits (SPA, HTRF) | Homogeneous assay technologies that eliminated separation steps, enabling rapid "mix-and-read" protocols essential for automation and high throughput [15]. |

| Recombinant Proteins/Enzymes | Purified, often recombinant, biological targets (e.g., kinases, proteases, receptors) used in biochemical assays to measure compound-induced modulation of activity [14] [15]. |

| Cell Lines for Cell-Based Assays | Engineered mammalian or microbial cells, produced in large-scale cell culture, expressing a target protein or used in phenotypic screens to study compound effects in a cellular context [15]. |

| 384-Well Microplates | The standard reaction vessel for HTS, allowing for a high density of tests with minimal reagent and compound consumption compared to the earlier 96-well format [14] [15]. |

| Assay Buffers and Biochemicals | Specialized solutions and reagents (substrates, cofactors, ions) required to maintain optimal pH, ionic strength, and biochemical conditions for the specific target being screened. |

The industrial adoption and technological breakthroughs of HTS in the 1990s fundamentally reshaped the drug discovery landscape. By moving from a small-scale, manual, chemistry-support service to a large-scale, automated, and data-intensive discipline, HTS enabled the empirical screening of entire compound libraries. The convergence of automation, novel assay technologies, miniaturization, and integrated data management created a new paradigm for identifying bioactive molecules, solidifying HTS as an indispensable engine for pharmaceutical innovation at the turn of the millennium [14] [15].

In the life sciences, particularly in drug discovery, a fundamental shift is redefining the approach to scientific inquiry. For decades, hypothesis-driven research dominated, following a linear path where scientists began with a specific biological hypothesis and designed discrete experiments to test it [17]. This traditional model operates on a "one target, one drug" philosophy, which struggles to address the overwhelming complexity of human biological systems [17].

In contrast, systematic, data-rich exploration represents a paradigm shift toward holistic investigation. This approach leverages high-throughput technologies to generate massive datasets from which patterns and hypotheses can be extracted [18] [17]. It marks a pivotal move from a reductionist view to a systems-level understanding of biology, using computational tools to find meaningful patterns within complexity that overwhelms human cognition [17]. The following table summarizes the core distinctions between these two paradigms.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Research Paradigms

| Characteristic | Hypothesis-Driven Research | Systematic, Data-Rich Exploration |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Specific biological hypothesis [19] | Large-scale data generation without pre-set hypotheses [19] [20] |

| Experimental Design | Targeted, discrete experiments | Unbiased, high-throughput screening of vast libraries [18] [12] |

| Primary Approach | Tests a single predetermined model | Discovers patterns and generates hypotheses from data [19] [20] |

| Underlying Philosophy | Reductionist: "One target, one drug" [17] | Holistic: Systems-level understanding of biology [17] |

| Data Handling | Collects only data relevant to the initial hypothesis [21] | Archives primary data for future re-analysis and re-use [21] |

| Typical Output | Validation or rejection of a specific hypothesis | Identification of multiple, often unexpected, correlations and candidates [19] |

Quantitative Comparison: Performance and Outcomes

The adoption of data-rich, high-throughput methods is driven by tangible improvements in research efficiency and output. The following data, compiled from industry reports and scientific literature, quantifies this performance gap.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Research Methodologies in Drug Discovery

| Metric | Traditional Hypothesis-Driven Methods | High-Throughput/Data-Rich Methods | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Identification & Validation Timeline | 2-3 years [17] | <1 year [17] | Industry Analysis [17] |

| Hit-to-Lead Timeline | 2-3 years [17] | <1 year [17] | Industry Analysis [17] |

| Screening Throughput | Low (tens to hundreds of samples) | High (up to 100,000+ data points daily) [18] | Scientific Literature [18] |

| Reported Success Rate (Phase II Trials) | ~29% [17] | >50% (projected with AI/stratification) [17] | Industry Analysis [17] |

| Market Growth (CAGR 2025-2035) | N/A (Established standard) | 10.0% - 10.6% [12] [22] | Market Research [12] [22] |

| Reported Hit Identification Improvement | Baseline | Up to 5-fold improvement [22] | Market Research [22] |

The economic impetus for this shift is clear. The high-throughput screening market, valued at USD 32.0 billion in 2025, is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.0% to reach USD 82.9 billion by 2035 [12]. Another report forecasts a CAGR of 10.6% from 2025 to 2029 [22]. This robust growth is fueled by the need to improve the dismal success rates in drug development, where only about 7.9% of drugs entering Phase I trials reach the market [17].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Traditional Hypothesis-Driven Workflow

The classical approach is sequential and guided by a prior reasoning. A typical protocol for identifying a novel enzyme inhibitor is outlined below.

Protocol: Hypothesis-Driven Inhibitor Discovery

- Hypothesis Formulation: Based on a literature review, the researcher hypothesizes that inhibiting "Enzyme X" will produce a therapeutic effect in "Disease Y."

- Experimental Design: A single, known compound "Z" is selected for testing based on its structural similarity to the enzyme's natural substrate.

- Assay Execution:

- A low-throughput, bespoke assay is developed (e.g., a colorimetric reaction).

- The assay is run in duplicate or triplicate with carefully controlled conditions.

- Results are collected manually or with simple instrumentation.

- Data Analysis: Data is analyzed to determine if a statistically significant difference exists between the treated and control groups, specifically regarding Enzyme X's activity.

- Conclusion: The hypothesis is either supported or rejected, leading to a new, narrow hypothesis for the next cycle.

Systematic, Data-Rich Exploration Workflow

High-throughput methods invert this process, letting the data guide the discovery. A standard protocol for a high-throughput screen (HTS) is detailed below.

Protocol: High-Throughput Screening for Hit Identification

- Assay Development and Miniaturization:

- A biological assay is designed to report on the desired activity (e.g., cell viability, protein-protein interaction).

- The assay is miniaturized into 384-well or 1536-well microplates to reduce reagent costs and increase throughput [22].

- Automated Screening:

- Robotic liquid handlers dispense nanoliter volumes of compounds and reagents into the microplates [22].

- A large, diverse compound library (containing thousands to millions of compounds) is screened against the target.

- Positive controls and negative controls are included on every plate to ensure quality (e.g., using Z-factor calculations) [22] [23].

- Automated Data Acquisition:

- Data Processing and Hit Identification:

- Raw data is processed and normalized. Dose-response curves are generated for active compounds to determine IC50 values [22].

- Statistical algorithms and machine learning models are applied to identify "hits" – compounds that show desired activity above a statistically defined threshold [22] [17].

- Data mining techniques like cluster analysis are used to group active compounds by structural or functional similarity [20].

- Hypothesis Generation:

- The patterns observed in the active compounds (e.g., common chemical scaffolds) form the basis for new hypotheses about structure-activity relationships, which guide the next round of compound design or selection [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The implementation of systematic, data-rich exploration relies on a specialized set of tools and reagents that enable automation, miniaturization, and large-scale data generation.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for High-Throughput Workflows

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Workflow | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Based Assays | Deliver physiologically relevant data and predictive accuracy in early drug discovery [12]. | Direct assessment of compound effects on live cells; used in 39.4% of HTS technologies [12]. |

| Microplates (384/1536-well) | Enable assay miniaturization, reducing reagent volumes and costs while dramatically increasing throughput [22]. | The standard platform for robotic screening of large compound libraries. |

| Robotic Liquid Handling Systems | Automate the precise dispensing of liquids across thousands of samples, ensuring speed and reproducibility [22]. | Integrated into HTS platforms to execute assays at an unprecedented scale [22]. |

| Label-Free Detection Kits | Allow measurement of biological interactions without fluorescent or radioactive labels, providing a more direct readout [22]. | Used in target identification and validation studies to minimize assay interference. |

| Specialized Reagents & Kits | Provide reliable, ready-to-use consumables that ensure reproducibility and accuracy in screening workflows [12]. | The largest product segment (36.50%), including assay kits for specific targets like kinases or GPCRs [12]. |

| Informatics Software | Provides the software control of physical devices and manages the organization and storage of generated electronic data [18]. | Controls HTS instruments, stores data, and facilitates data mining and machine learning analysis. |

The transition from hypothesis-driven to systematic, data-rich exploration is not merely a change in techniques but a fundamental evolution in the philosophy of scientific discovery. While the traditional model will always have its place for testing well-defined questions, the complexity of modern biology and the unsustainable costs of traditional drug development necessitate a more comprehensive approach. The quantitative data shows that high-throughput methods offer dramatic improvements in speed, efficiency, and the potential for serendipitous discovery [19]. The future of research, particularly in drug discovery, lies in the synergistic integration of both paradigms: using data-rich exploration to generate robust hypotheses and employing targeted, hypothesis-driven methods to validate them, thereby creating a more powerful and efficient engine for innovation.

Inside the High-Throughput Toolbox: Assays, Automation, and AI Integration

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, enabling the rapid testing of thousands to millions of chemical compounds to identify those with biological activity. The choice of screening platform—biochemical, cell-based, or phenotypic—profoundly influences the type of hits identified, the biological relevance of the data, and the subsequent drug development pathway. This guide provides an objective comparison of these three primary HTS assay types, framing them within the broader thesis of evolving drug discovery paradigms, from traditional reductionist methods to more holistic, high-throughput optimization strategies.

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is an automated experimental platform that allows researchers to quickly conduct millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological tests. The primary goal of HTS is to rapidly identify active compounds (hits) that modulate a particular biological pathway or target [24]. By combining miniaturized assay formats (such as 384- or 1536-well plates), robotics, sensitive detectors, and data processing software, HTS accelerates the early stages of drug discovery, transforming a process once compared to "finding a needle in a haystack" into a systematic, data-rich endeavor [24].

The global HTS market, valued at approximately $18.8 billion for 2025-2029, reflects its critical role, with a projected compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.6% [22]. This growth is propelled by rising R&D investments in pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases, and continuous technological advancements in automation and data analytics [22] [25]. The market is further segmented by technology, with cell-based assays expected to maintain a dominant position due to their physiological relevance and versatility in studying complex biological systems [25].

Comparative Analysis of HTS Assay Platforms

The three main HTS platforms differ fundamentally in their design, biological complexity, and the nature of the information they yield. The table below provides a structured, high-level comparison of biochemical, cell-based, and phenotypic screening platforms.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of HTS Screening Platforms

| Feature | Biochemical Assays | Cell-Based Assays | Phenotypic Assays |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening Principle | Target-based; measures compound interaction with a purified protein or nucleic acid [24] [26]. | Mechanism-informed; measures compound effect in a live cellular context, often on a predefined target or pathway [27]. | Phenotype-based; measures compound-induced changes in observable cellular or organismal characteristics without a predefined molecular target [28] [26]. |

| Biological Context | Simplified, non-cellular system using isolated components [24] [27]. | Intact living cells, preserving aspects of the intracellular environment like membrane context and protein folding [27]. | Complex, physiologically relevant systems including 2D/3D cell cultures, organoids, or whole organisms [28] [26]. |

| Primary Advantage | High mechanistic clarity, control, and suitability for ultra-HTS [24]. | Balances physiological relevance with the ability to probe specific mechanisms [27]. | Unbiased discovery of novel mechanisms and first-in-class drugs; captures system-level biology [28] [26]. |

| Key Limitation | May not reflect compound behavior in a physiological cellular environment [27]. | May not fully capture the complexity of tissue-level or organismal physiology [26]. | Requires subsequent, often complex, target deconvolution to identify the mechanism of action (MoA) [28] [26]. |

| Typical Hit Rate | Varies; computational AI screens report ~6-8% [29]. | Varies; foundational for many target validation and screening cascades. | Historically a key source of first-in-class medicines [28]. |

| Best Suited For | Enzyme kinetics, receptor-ligand binding, and initial ultra-HTS of large compound libraries [24]. | Studying ion channels, GPCRs, and intracellular targets in a more native context; pathway analysis [27]. | Diseases with complex or unknown etiology; discovering novel therapeutic mechanisms [28] [26]. |

Biochemical Screening Assays

Principles and Workflow

Biochemical assays investigate the activity of a purified target, such as an enzyme, receptor, or nucleic acid, in an isolated, controlled environment. The core principle is to directly measure the effect of a compound on the target's biochemical function, for instance, by monitoring enzyme-generated products or ligand displacement [24]. This approach is a hallmark of target-based drug discovery (TDD).

The workflow begins with the purification of the target protein. Compounds are then introduced into the reaction system. Detection of activity often relies on robust, miniaturized-friendly chemistries such as fluorescence polarization (FP), time-resolved FRET (TR-FRET), luminescence, or absorbance [24]. The Transcreener ADP² Assay is an example of a universal biochemical assay that can be applied to various enzyme classes like kinases, ATPases, and GTPases by detecting a common product (ADP) [24].

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for a biochemical HTS assay, from target identification to hit validation.

Experimental Protocols and Data

A key metric for validating any HTS assay, including biochemical formats, is the Z'-factor, a statistical parameter that assesses the robustness and quality of the assay. A Z'-factor between 0.5 and 1.0 is considered excellent [24]. For enzyme inhibition assays, the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) is a critical quantitative measure of a compound's potency, indicating the concentration required to inhibit the target's activity by 50% [24].

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics in Biochemical HTS [24]

| Metric | Description | Ideal Value/Range |

|---|---|---|

| Z'-factor | Measure of assay robustness and signal dynamic range. Incorporates both the signal window and the data variation. | 0.5 - 1.0 (Excellent) |

| Signal-to-Noise (S/N) | Ratio of the specific assay signal to the background noise level. | > 10 (High) |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | Measure of well-to-well and plate-to-plate reproducibility. | < 10% |

| IC50 | Concentration of an inhibitor where the response is reduced by half. | Compound-dependent; lower indicates higher potency. |

Cell-Based Screening Assays

Principles and Workflow

Cell-based assays utilize live cells as biosensors to evaluate the effects of compounds in a more biologically relevant context than biochemical assays. These systems preserve critical aspects of the cellular environment, such as membrane integrity, protein-protein interactions, post-translational modifications, and cellular metabolism [27]. This makes them indispensable for studying complex target classes like G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), ion channels, and intracellular protein-protein interactions, whose activity depends on a native membrane and cellular context [27].

The workflow involves selecting and preparing an appropriate cell model, which can range from standard immortalized lines to more physiologically relevant primary cells or stem cell-derived cultures. After compound treatment, the biological readout is measured. This can be a specific molecular event, such as calcium flux for ion channels, or a more complex, multiparametric output from high-content imaging [27].

Figure 2: A generalized workflow for a cell-based HTS assay, showing multiple pathways for measuring cellular responses.

Experimental Protocols and Data

Cell-based assays encompass a wide range of technologies, each with specific applications and readouts. Reporter gene assays, for example, measure transcriptional activation using luciferase or GFP, while calcium flux assays provide real-time functional data for ion channels and GPCRs [27]. High-content screening (HCS) utilizes automated microscopy and image analysis to capture complex phenotypic changes, such as in cell morphology or protein localization [27].

Table 3: Common Cell-Based Assay Types and Their Applications [27]

| Assay Type | Detection Method | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reporter Gene Assay | Luminescence, Fluorescence (GFP) | Transcriptional activation, pathway modulation. | Quantitative, pathway-specific, HTS-compatible. | May not reflect post-translational regulation; artificial promoter context. |

| Calcium Flux / Electrophysiology | Fluorescent dyes, Microelectrodes | Functional screening of ion channels, GPCRs. | Real-time functional data; gold standard for ion channels. | Requires specialized equipment; can be sensitive to variability. |

| Viability / Cytotoxicity | Resazurin reduction, ATP detection (Luminescence) | Toxicity screening, anticancer drug discovery. | Simple, scalable, and cost-effective. | Provides limited mechanistic insight. |

| High-Content Screening (HCS) | Automated microscopy & image analysis | Multiparametric analysis (e.g., morphology, translocation). | Captures complex phenotypes; rich data output. | Data-intensive; requires significant analysis expertise. |

Phenotypic Screening Assays

Principles and Workflow

Phenotypic screening identifies bioactive compounds based on their ability to induce a desired change in the observable characteristics (phenotype) of a cell, tissue, or whole organism, without requiring prior knowledge of a specific molecular target [28] [26]. This approach is inherently unbiased and has been responsible for the discovery of numerous first-in-class therapeutics, as it embraces the complexity of biological systems and can reveal unexpected mechanisms of action (MoA) [28].

Modern phenotypic screening has resurged due to advances in high-content imaging, AI-powered data analysis, and the development of more predictive biological models such as 3D organoids, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and organ-on-a-chip technologies [26]. These innovations allow for the capture of complex, multiparametric readouts that provide a systems-level view of compound effects.

The workflow begins with selecting a biologically relevant model system that recapitulates key aspects of the disease phenotype. After compound treatment, high-content data is collected, often through automated imaging. Sophisticated data analysis, increasingly aided by machine learning, is then used to identify compounds that induce the desired phenotypic profile [30]. A significant subsequent step is target deconvolution, the process of identifying the molecular target(s) responsible for the observed phenotypic effect [28] [26].

Figure 3: A generalized workflow for phenotypic screening, highlighting the critical and often challenging step of target deconvolution.

Experimental Protocols and Data

The "Cell Painting" assay has become a powerful, standardized methodology in phenotypic screening. It uses a set of fluorescent dyes to label multiple cellular components (e.g., nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, cytoskeleton), generating a rich morphological profile for each compound [30]. Deep learning models can be trained on these Cell Painting images, combined with single-concentration bioactivity data, to predict compound activity across diverse biological assays. One large-scale study reported an average predictive performance (ROC-AUC) of 0.74 across 140 different assays, demonstrating that phenotypic profiles contain widespread information related to bioactivity [30].

The "Phenotypic Screening Rule of 3" has been proposed as a framework to enhance the translatability of phenotypic assays, emphasizing the importance of using: 1) disease-relevant models, 2) disease-relevant stimuli, and 3) disease-relevant readouts [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The execution of robust HTS campaigns relies on a suite of specialized reagents, instruments, and materials. The following table details key solutions used across different HTS platforms.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTS Assays

| Item / Solution | Function in HTS | Common Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Microplates | Miniaturized reaction vessel for assays. | 96-, 384-, and 1536-well plates are standard. Material (e.g., polystyrene, glass) is chosen based on the assay and detection method. |

| Universal Detection Kits | Detect common reaction products for flexible assay design. | Kits like the Transcreener ADP² Assay can be used for any enzyme that generates ADP (kinases, ATPases), enabling a "one-assay-fits-many" approach [24]. |

| Cell Painting Dye Set | Standardized fluorescent labeling for phenotypic profiling. | A cocktail of 6 dyes labeling nuclei, nucleoli, ER, mitochondria, cytoskeleton, Golgi, etc., to generate a multiparametric morphological profile [30]. |

| Viability/Cytotoxicity Assay Kits | Measure cell health, proliferation, or death. | Reagents like resazurin (which measures metabolic activity) or ATP-detection kits (e.g., luminescence-based CellTiter-Glo). |

| High-Content Imaging Systems | Automated microscopes for capturing complex phenotypic data. | Systems from vendors like PerkinElmer, Thermo Fisher, and Yokogawa that automate image acquisition and analysis for cell-based and phenotypic assays. |

| AI/ML Bioactivity Prediction Models | Computationally prioritize compounds from vast chemical libraries. | Platforms like AtomNet use convolutional neural networks for structure-based screening, while others use Cell Painting data for phenotypic-based prediction [30] [29]. |

Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

The field of HTS is continuously evolving, driven by technological innovations and the need for greater predictive power in drug discovery.

- Integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML): AI is transforming HTS by enabling the virtual screening of ultra-large chemical libraries containing billions of molecules, a scale impossible for physical screening [29]. Empirical studies demonstrate that AI can achieve high hit rates (e.g., 6.7% in one 318-target study) and identify novel scaffolds, positioning it as a viable alternative or complement to primary HTS [29]. Furthermore, ML models are being used to predict bioactivity directly from phenotypic profiles, such as Cell Painting images, helping to design smaller, more focused screening campaigns [30].

- Advanced Biological Models: There is a strong shift towards using more physiologically relevant models in HTS, especially in cell-based and phenotypic screening. This includes the adoption of 3D cell cultures (spheroids, organoids), iPSC-derived cells, and organ-on-a-chip systems to better mimic human tissue and disease biology [26] [31].

- Automation, Miniaturization, and Data Analytics: The ongoing integration of advanced robotics, microfluidics (Lab-on-a-Chip), and label-free detection technologies continues to increase throughput, reduce reagent costs, and generate richer datasets [22] [25]. The analysis of these complex datasets is increasingly dependent on sophisticated bioinformatics and data mining tools.

In conclusion, the choice between biochemical, cell-based, and phenotypic screening is not a matter of selecting the universally "best" platform, but rather the most appropriate tool for a specific biological question within the drug discovery pipeline. Biochemical assays offer precision and high throughput for defined targets, cell-based assays provide essential physiological context for target classes like GPCRs, and phenotypic screening enables unbiased discovery for complex diseases. The future of HTS lies in the strategic integration of these platforms, augmented by powerful AI and predictive biological models, to systematically bridge the gap between traditional reductionist methods and the complex reality of human disease.

The landscape of drug discovery and life sciences research has undergone a profound transformation, shifting from traditional, manual methods to integrated, high-throughput automation. This evolution is driven by the relentless pressure to accelerate therapeutic development while containing soaring costs, which can exceed $2 billion for a single marketed drug [32]. Traditional methods, reliant on manual pipetting and single-experiment approaches, are increasingly incompatible with the scale and precision required for modern genomics, proteomics, and large-scale compound screening [33].

This guide provides an objective comparison of the core technologies that form the modern laboratory automation engine: Robotic Liquid Handlers, Microplate Technologies, and Detection Systems. By examining product performance data and experimental protocols, we aim to furnish researchers and drug development professionals with the evidence needed to make informed decisions in configuring high-throughput workflows that offer superior efficiency, reproducibility, and data quality compared to traditional optimization methods.

The automated liquid handling and microplate systems markets are experiencing robust growth, fueled by increased R&D activities and the widespread adoption of automation [34] [35] [36]. The following tables summarize key market data and growth metrics.

Table 1: Global Market Size and Growth Projections for Automation Technologies

| Technology Segment | Market Size (2024/2025) | Projected Market Size | CAGR | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automated Liquid Handlers [34] | USD 249.3 million growth (2024-2029) | 5.8% (2024-2029) | Drug discovery demand, high-throughput screening, assay miniaturization | |

| Robotic Liquid Handling Systems [37] | USD 7.96 billion (2025) | USD 13.39 billion (2033) | 6.2% (2025-2033) | Laboratory automation demand, error reduction, need for data accuracy |

| Microplate Systems [35] | USD 1.98 billion (2025) | USD 3.72 billion (2035) | 6.5% (2025-2035) | High-throughput screening, automation in life sciences, drug discovery, clinical diagnostics |

| Microplate Systems [36] | USD 1.42 billion (2025) | USD 2.13 billion (2029) | 10.7% (2025-2029) | Increasing chronic diseases, personalized medicine, healthcare infrastructure development |

Table 2: Regional Market Analysis and Key Trends

| Region | Market Characteristics & Share | Growth Catalysts |

|---|---|---|

| North America | Largest market; >35% of global ALH market growth [34]; leadership in pharmaceutical R&D [38]. | Robust pharmaceutical ecosystem, significant R&D funding, high adoption of AI and lab automation [34]. |

| Europe | Significant market with strong growth potential [37]. | Emphasis on automation trends and regulatory frameworks [37]. |

| Asia-Pacific | Expected highest growth rate [37]; rapidly expanding life science industries [38]. | Growing investments in healthcare infrastructure, burgeoning biotechnology sector [35] [38]. |

Comparative Analysis of Robotic Liquid Handling Systems

Robotic liquid handlers are the cornerstone of the automation engine, designed to replace error-prone manual pipetting. They offer unmatched precision, reproducibility, and throughput in sample and reagent preparation.

Technology Performance Comparison

Table 3: Key Performance Indicators: Traditional vs. High-Throughput Liquid Handling

| Performance Characteristic | Traditional Manual Pipetting | Automated Liquid Handling |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Low (limited by human speed and endurance) | High (can process thousands of samples per run) [32] |

| Precision & Accuracy | Subject to human error and variability; reduced with fatigue [33] | High (software-controlled; precision at nanoliter scales) [32] [39] |

| Reproducibility | Low (varies between operators and days) | High (fully automated, consistent protocols) [32] [33] |

| Operational Cost | Lower upfront cost, higher long-term labor costs | Higher upfront investment, lower long-term cost per sample [32] |

| Reagent Consumption | Higher volumes (typically microliters) | Greatly reduced volumes (nanoliters to picoliters), enabling miniaturization [32] [39] |

| Error Rate | Higher risk of cross-contamination and procedural errors [33] | Minimal with non-contact technologies; integrated barcode tracking [32] [39] |

Leading Vendor and Product Analysis

The market includes established players and specialized innovators, each offering systems with distinct advantages.

Table 4: Comparison of Select Automated Liquid Handling Systems

| Vendor | Product/Platform | Key Technology | Volume Range | Notable Features & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agilent Technologies [39] | Bravo Automated Liquid Handling Platform | Swappable pipette heads (disposable tips) | 300 nL - 250 µL | Compact design; fits in laminar flow hood; customizable for 96-, 384-, 1536-well plates |

| Labcyte (a Revvity company) [39] | Echo Liquid Handlers | Acoustic Droplet Ejection (ADE) | 2.5 nL and above | Non-contact; no tip costs; minimal cross-contamination; for HTS and assay miniaturization |

| Tecan [39] | D300e Digital Dispenser | Thermal Inkjet Technology | 11 pL - 10 µL | Very low dead volume (2µL); ideal for assay development and dose-response experiments |

| PerkinElmer [39] | JANUS G3 Series | Varispan arm; Automatic interchangeable MDT | Wide dynamic range | Modular workstations; customizable for throughput, capacity, and volume range |

| Hamilton Company [40] | STAR System | Air displacement pipetting | Wide dynamic range | Excellent for clinical settings requiring strict regulatory compliance [40] |

| Eppendorf [40] | Various Systems | Compact, easy-to-use systems; suitable for academic labs |

Comparative Analysis of Microplate Technologies

Microplates are the universal substrate for high-throughput experiments, and their associated handlers, washers, and readers are critical for streamlined workflows.

Microplate System Segmentation and Applications

Table 5: Microplate System Types, Applications, and Key Players

| System Type | Common Applications | Key Features & Trends | Representative Companies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microplate Readers (Multi-mode & Single-mode) [36] | Drug discovery, clinical diagnostics, genomics & proteomics research | Versatility; multimode readers combine absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence; AI-driven data analysis [35] | Thermo Fisher, Molecular Devices, BMG Labtech |

| Microplate Washers [36] | ELISA, cell-based assay washing | Automated washing improves reproducibility; integrated with LIMS [35] | Bio-Rad, Thermo Fisher, PerkinElmer |

| Microplate Handlers [36] | Any high-throughput workflow involving plate movement | Robotic arms and stackers for full walk-away automation; integration with liquid handlers and readers | Tecan, Hamilton, Hudson Robotics |

Detection Systems and Data Analysis

Modern detection systems, particularly microplate readers, are the final critical component that transforms a physical assay into quantifiable data. The trend is firmly toward multi-mode readers, which combine multiple detection methods (e.g., absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence) in a single instrument, enhancing laboratory versatility and efficiency [36]. This eliminates the need for multiple dedicated instruments and conserves bench space.

A key differentiator between traditional and high-throughput methods is data acquisition and analysis. High-Throughput Screening (HTS) generates a massive amount of data that is challenging to process manually. Automated systems allow for rapid data collection and use dedicated software to generate almost immediate insights, minimizing the tedious, time-consuming, and error-prone manual analysis [32]. The integration of AI and machine learning is further revolutionizing this space, enabling more efficient data interrogation and the identification of promising compounds with higher success rates [35] [38].

Experimental Protocols and Workflow Integration

To illustrate the practical advantages of high-throughput systems, let's examine a standard drug discovery protocol.

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Protocol for Drug Discovery

Objective: To screen a large library of chemical compounds for activity against a specific disease target. Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Compound Library: A curated collection of thousands to millions of small molecules or biologics [32].

- Target Protein: The purified protein (e.g., enzyme, receptor) implicated in the disease.

- Assay Reagents: Specific substrates, fluorescent or luminescent probes needed to detect target activity.

- Cell Line: Engineered cells for cell-based assays, if applicable.

- Microplates: 384-well or 1536-well plates to maximize throughput and minimize reagent use [39].

Methodology:

- Protocol Design: The assay conditions (concentrations, incubation times) are defined and programmed into the liquid handler's software.

- Compound Transfer: Using an automated liquid handler (e.g., Agilent Bravo, Labcyte Echo), nanoliter volumes of compounds from the library are dispensed into the assay microplates [39].

- Reagent Dispensing: The liquid handler adds a consistent volume of the target protein and assay reagents to all wells.

- Incubation and Washing: Microplate handlers move plates to incubators for a defined period. Microplate washers may be used for specific assay types like ELISAs.

- Signal Detection: Plates are transferred to a multi-mode microplate reader to measure the assay signal (e.g., fluorescence intensity).

- Data Analysis: Software analyzes the raw data, normalizes it against controls, and identifies "hits" - compounds that show desired activity [32].

High-Throughput Screening Workflow

The following diagram visualizes the fully automated, iterative workflow described in the HTS protocol, highlighting the seamless integration of robotic liquid handlers, microplate technologies, and detection systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 6: Key Reagents and Consumables for Automated High-Throughput Workflows

| Item | Function in Experiment | Considerations for High-Throughput |

|---|---|---|

| Assay Kits | Provide optimized buffers, reagents, and protocols for specific biological assays (e.g., kinase activity, cell viability). | Ensure compatibility with automated dispensers and miniaturized volumes in 384- or 1536-well formats. |

| Fluorescent/Luminescent Probes | Generate a measurable signal proportional to the biological activity or quantity of the target. | Select probes with high sensitivity and stability suitable for the detection system (reader). |

| High-Quality Buffers & Solvents | Maintain pH and ionic strength; dissolve compounds and reagents. | Purity is critical to prevent clogging of fine dispense tips and avoid chemical interference. |

| Low-Binding Microplates | Serve as the reaction vessel for assays. | Choice of plate material (e.g., polystyrene, polypropylene) and surface treatment is vital to minimize analyte loss. |

| Disposable Tips & Labware | Used by liquid handlers for reagent transfer; prevent cross-contamination. | A major consumable cost; balance quality (precision) with expense. Non-contact dispensers eliminate tip costs [39]. |

The evidence from market data, performance comparisons, and experimental protocols clearly demonstrates the superior efficacy of integrated high-throughput systems over traditional manual methods. The synergy between robotic liquid handlers, advanced microplate systems, and sensitive detection technologies creates an automation engine that fundamentally enhances research productivity.

This engine enables researchers to:

- Accelerate discovery timelines by orders of magnitude.

- Enhance data quality and reproducibility by eliminating human variability.

- Reduce operational costs in the long term through miniaturization and efficiency.

- Expand the scope of scientific inquiry by making large-scale experimentation feasible.

The future of this field points towards even greater integration, intelligence, and accessibility. The continued adoption of AI and machine learning for experimental design and data analysis, alongside the development of more modular and cost-effective systems, will further democratize high-throughput capabilities. For researchers and drug developers, embracing and understanding this integrated automation engine is no longer optional but essential for remaining at the forefront of scientific innovation.

The evolution from 96-well to 1536-well microplate formats represents a critical response to the increasing demands for efficiency and scalability in life science research and drug discovery. Miniaturization of assay formats has emerged as a fundamental strategy for enhancing throughput while significantly reducing reagent consumption and operational costs. This transition from traditional to high-throughput optimization methods enables researchers to conduct increasingly complex experiments on an unprecedented scale, accelerating the pace of scientific discovery.

The microplate, first conceived in the 1950s by Hungarian microbiologist Dr. Gyula Takátsy, has undergone substantial transformation from its original 72-well design [41] [42]. The standardization of the 96-well plate in the late 20th century established a foundation for automated laboratory systems, but continuous pressure to increase throughput while reducing costs has driven the adoption of higher-density formats [41] [43]. The 384-well plate initially served as an intermediate step, but the 1536-well format has emerged as the current standard for ultra-high-throughput screening (uHTS) in pharmaceutical research and development [44]. This progression reflects a broader trend in life sciences toward miniaturization, mirroring developments in other technological fields where smaller, denser, and more efficient systems have replaced their bulkier predecessors [45] [46].

Comparative Analysis of Microplate Formats

The selection of an appropriate microplate format requires careful consideration of multiple interrelated factors, including well count, volume capacity, instrumentation requirements, and application-specific needs. The progression from 96-well to 1536-well formats represents not merely a quantitative increase in well density, but a qualitative shift in experimental approach and infrastructure requirements.

Technical Specifications and Physical Dimensions

The standardization of microplate dimensions by the Society for Biomolecular Screening (now SLAS) and ANSI has been crucial for ensuring compatibility with automated laboratory systems [41] [43]. Despite this standardization, significant variations exist in well capacities and geometric configurations across different formats, directly influencing their application suitability.

Table 1: Physical Specifications and Characteristics of Common Microplate Formats

| Format | Well Number | Standard Well Volume (µL) | Recommended Working Volume (µL) | Well Bottom Shape | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 96-Well | 96 | 300-350 | 100-300 | F, U, C, V | Cell culture, ELISA, general assays |

| 384-Well | 384 | 100-120 | 30-100 | F, U, C | HTS, compound screening, biochemical assays |

| 1536-Well | 1536 | 10-15 | 5-25 | F (rounded) | uHTS, specialized screening campaigns |

The dimensional progression between formats follows a consistent pattern. A 96-well plate features a standard footprint of 127.76 mm × 85.48 mm, with wells arranged in an 8 × 12 matrix [42] [43]. The 384-well format increases density by reducing well spacing, arranging wells in a 16 × 24 matrix within the same footprint [41]. The 1536-well format further maximizes well count with a 32 × 48 arrangement, drastically reducing per-well volume capacity to approximately 10-15µL [44]. This reduction in volume presents both opportunities for reagent savings and challenges in liquid handling precision.

Material Composition and Optical Properties

Microplate material selection critically influences experimental outcomes, particularly in detection-intensive applications. Manufacturers typically utilize various polymers, each offering distinct advantages for specific applications.

Table 2: Microplate Materials and Their Application Suitability

| Material | Light Transmission Range | Autofluorescence | Temperature Resistance | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene (PS) | >320 nm | Moderate | Low | Cell culture, ELISA, general absorbance assays |

| Cycloolefin (COC/COP) | 200-400 nm (UV) | Low | Moderate | UV absorbance, DNA/RNA quantification, fluorescence |

| Polypropylene (PP) | Variable | Low | High | PCR, compound storage, high-temperature applications |

| Polycarbonate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | General purpose, filtration plates |