Green Chemistry in Organic Synthesis: Principles, Methods, and Metrics for Sustainable Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the application of Green Chemistry principles in organic synthesis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Green Chemistry in Organic Synthesis: Principles, Methods, and Metrics for Sustainable Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the application of Green Chemistry principles in organic synthesis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational shift towards sustainable methodologies, showcases cutting-edge applications like metal-free catalysis and bio-based solvents, and offers practical troubleshooting for optimizing synthetic routes. The content also details robust validation frameworks and comparative metrics, including AGREE and GAPI tools, to quantitatively assess the environmental footprint of chemical processes. By integrating these strategies, the article aims to equip practitioners with the knowledge to design efficient, safer, and more sustainable synthetic pathways, ultimately advancing green practices in pharmaceutical and fine chemical industries.

The Pillars of Green Chemistry: Core Principles for Modern Organic Synthesis

Green Chemistry, defined as the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances, represents a fundamental shift in how chemists approach molecular design and synthesis [1] [2]. Originating from the environmental activism of the 1960s and formally established in the 1990s through the foundational work of Paul Anastas and John Warner, Green Chemistry has evolved from a conceptual framework to an essential guiding principle across research and industrial landscapes [3]. The field emerged from a growing recognition that traditional chemical processes often generated substantial waste and relied on hazardous materials, necessitating a proactive, prevention-oriented approach [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting Green Chemistry principles is no longer optional but imperative for developing sustainable synthetic methodologies that minimize environmental impact while maintaining scientific and economic viability [4].

This whitepaper examines the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry through the specific lens of organic synthesis, providing a technical framework for integrating these principles into research and development workflows. The transition toward greener synthetic protocols aligns with broader initiatives such as the European Green Deal and global Sustainable Development Goals, reflecting the chemical community's commitment to environmental stewardship [2]. By emphasizing waste prevention, atom economy, and safer chemical design, Green Chemistry offers a systematic approach to addressing the environmental challenges associated with traditional synthetic organic chemistry while fostering innovation in reaction design and process optimization [3] [5].

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry: A Detailed Analysis

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry provide a comprehensive framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce their environmental footprint and potential health impacts [3] [5]. These principles guide researchers in developing synthetic methodologies that are efficient, sustainable, and inherently safer. The table below summarizes these principles and their core directives for synthetic chemists.

Table 1: The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry and Their Synthetic Implications

| Principle | Core Concept | Relevance to Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Prevention | Prevent waste rather than treat or clean up after formation [6] [2] | Design processes that minimize by-product generation [2] |

| 2. Atom Economy | Maximize incorporation of all starting materials into final product [3] [6] | Select reactions where most reactant atoms appear in desired product [3] |

| 3. Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses | Design synthetic methods using/ generating substances with little toxicity [6] [5] | Replace hazardous reagents with safer alternatives; develop milder reaction conditions [1] |

| 4. Designing Safer Chemicals | Design chemical products to achieve desired function with minimal toxicity [6] [5] | Incorporate molecular features that maintain efficacy while reducing toxicity [3] |

| 5. Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries | Minimize use of auxiliary substances where possible [6] [5] | Prefer water or biodegradable solvents over volatile organic compounds [7] [3] |

| 6. Design for Energy Efficiency | Conduct reactions at ambient temperature and pressure [6] [5] | Develop catalytic and other low-energy pathways [1] |

| 7. Use of Renewable Feedstocks | Prefer raw materials from renewable sources [6] [5] | Utilize biomass-derived building blocks instead of depleting feedstocks [7] |

| 8. Reduce Derivatives | Minimize unnecessary derivatization [6] [5] | Streamline synthesis to avoid protecting groups; use selective reactions [4] |

| 9. Catalysis | Prefer catalytic reagents over stoichiometric ones [6] [5] | Implement enzymatic, metal, or organocatalysts to enhance efficiency [4] |

| 10. Design for Degradation | Design chemical products to break down into innocuous substances [6] [5] | Incorporate hydrolyzable or biodegradable functional groups [6] |

| 11. Real-time Analysis | Develop real-time, in-process monitoring for hazard control [6] [5] | Implement analytical technologies for reaction monitoring [6] |

| 12. Inherently Safer Chemistry | Choose substances that minimize accident potential [6] [5] | Select reagents with higher boiling points, lower toxicity [6] |

Foundational Principles in Synthetic Context

Within the 12 principles, several hold particular significance for streamlining synthetic workflows in research and development. The principle of atom economy (Principle 2) emphasizes synthetic efficiency by measuring what percentage of reactant atoms are incorporated into the final desired product [3]. For example, the Diels-Alder reaction, a [4+2] cycloaddition, is considered highly atom-economical as it theoretically incorporates all atoms from the starting materials into the product without generating stoichiometric byproducts [3]. Similarly, catalysis (Principle 9) plays a transformative role in green synthesis by enabling more efficient transformations, reducing energy requirements, and often permitting the use of milder reaction conditions [4]. The pharmaceutical industry has pioneered the adoption of catalysis, with companies like AstraZeneca implementing nickel-based catalysts to replace precious metals like palladium in key reactions, resulting in reductions of more than 75% in CO₂ emissions, freshwater use, and waste generation [4].

The strategic selection of safer solvents and auxiliaries (Principle 5) represents another critical area for implementation in research laboratories. Traditional organic solvents such as chloroform and dichloromethane pose significant health and environmental concerns [8]. Green Chemistry promotes substitution with safer alternatives, including water, supercritical CO₂, ionic liquids, and bio-based solvents [7] [3]. Recent advances in mechanochemistry, which utilizes mechanical energy through grinding or ball milling to drive chemical reactions without solvents, demonstrate the potential for eliminating solvents entirely from certain synthetic pathways [7]. This approach not only removes the environmental burden of solvent use but can also enable novel transformations involving low-solubility reactants or compounds unstable in solution [7].

Quantitative Metrics for Green Chemistry Implementation

The implementation of Green Chemistry principles requires robust metrics to evaluate and compare the environmental performance of synthetic processes. These quantitative tools enable researchers to make data-driven decisions when developing new methodologies or optimizing existing routes.

Table 2: Key Green Chemistry Metrics for Process Evaluation

| Metric | Calculation | Application | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-Factor | Total mass of waste (kg) / Mass of product (kg) [2] | Measures waste generation efficiency of a process [2] | Lower is better (0 = no waste) |

| Atom Economy | (MW of desired product / Σ MW of reactants) × 100% [3] | Theoretical efficiency of incorporating atoms into product [3] | Higher is better (100% = all atoms utilized) |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | Total mass of materials (kg) / Mass of product (kg) [4] | Comprehensive measure of resource efficiency including solvents, reagents [4] | Lower is better (theoretical minimum = 1) |

| Carbon Efficiency | (Carbon in product / Carbon in reactants) × 100% | Measures retention of carbon in desired product | Higher is better (100% = all carbon in product) |

The E-factor, introduced in 1991, has become a standard metric for quantifying the waste generated during chemical manufacturing [2]. It is defined as the ratio of kilograms of waste produced per kilogram of product, with waste encompassing everything not incorporated into the final desired molecule, including solvents, reagents, and process aids [2]. Different sectors of the chemical industry exhibit characteristic E-factors, with pharmaceutical manufacturing typically having higher values due to complex multi-step syntheses and extensive purification requirements [2].

Process Mass Intensity (PMI) has gained prominence in pharmaceutical development as a more comprehensive metric that accounts for all mass inputs to a process, including water, solvents, reagents, and catalysts [4]. PMI is simply the sum of the quantity of input materials required to produce a single kilogram of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) [4]. AstraZeneca has developed novel methods to predict the PMI of all possible synthetic routes without experimentation, enabling chemists to select more sustainable pathways early in development [4]. This approach aligns with the green chemistry principle of waste prevention by designing efficiency into processes from the outset rather than optimizing after development.

Green Chemistry Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Solvent-Free Synthesis Using Mechanochemistry

Principle Demonstrated: Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries (Principle 5), Energy Efficiency (Principle 6) [7]

Objective: To perform chemical transformations without solvent use through mechanical energy input.

Detailed Protocol:

- Reaction Setup: Place solid reactants (typically 1-5 mmol total) in a milling jar with one or more grinding balls. The jar material (e.g., stainless steel, zirconia) should be selected based on chemical compatibility and required energy input.

- Milling Process: Secure the jar in a ball mill apparatus. Process at optimal frequency (typically 20-30 Hz) for a predetermined time (5-60 minutes). Monitoring reaction progression may require periodic stopping and sampling.

- Reaction Monitoring: Use techniques such as in-situ Raman spectroscopy or ex-situ Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to track reaction completion.

- Work-up: Following milling, the crude product may require minimal purification. Simple washing with a green solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate, ethanol) or recrystallization may suffice.

- Analysis: Characterize the final product using standard analytical techniques (NMR, MS, HPLC).

Research Application: This methodology has been successfully applied to synthesize pharmaceutical intermediates, metal-organic frameworks, and organic materials [7]. For example, researchers used mechanochemistry to synthesize solvent-free imidazole-dicarboxylic acid salts, which reduced solvent usage, provided high yields, and used less energy compared to solution-based synthesis [7].

Photocatalysis for Sustainable Reaction Activation

Principle Demonstrated: Energy Efficiency (Principle 6), Catalysis (Principle 9) [4]

Objective: To utilize visible light-activated catalysts for driving chemical transformations under mild conditions.

Detailed Protocol:

- Reaction Setup: In a dried glass vial or reaction tube, combine the substrate (0.1-0.5 mmol) and photocatalyst (typically 1-5 mol%). Common photocatalysts include ruthenium or iridium polypyridyl complexes, organic dyes, or semiconductor materials.

- Solvent Selection: Add an appropriate green solvent (e.g., acetonitrile, ethanol, or water, 2-5 mL) and ensure homogeneous mixing.

- Degassing: Sparge the reaction mixture with an inert gas (N₂ or Ar) for 5-10 minutes to remove oxygen, which can quench excited photocatalyst states.

- Irradiation: Place the reaction vessel in a photoreactor equipped with appropriate LED lamps (commonly blue or green light, 450-525 nm) with continuous stirring. Maintain temperature control (typically 20-25°C) using cooling fans or jacketed vessels.

- Reaction Monitoring: Track reaction progress using TLC, GC-MS, or HPLC at regular intervals.

- Work-up and Purification: After completion, concentrate the reaction mixture and purify using column chromatography or recrystallization.

- Catalyst Recovery: When possible, recover and reuse the photocatalyst through extraction or immobilization techniques.

Research Application: Photocatalysis enables access to reactive intermediates under mild conditions, facilitating transformations such as C-H functionalization, Minisci reactions, and desaturative synthesis of phenols from cyclohexanones [4]. AstraZeneca has implemented a photocatalyzed reaction that removed several stages from the manufacturing process for a late-stage cancer medicine, leading to more efficient manufacture with less waste [4].

Late-Stage Functionalization for Streamlined Synthesis

Principle Demonstrated: Reduce Derivatives (Principle 8), Atom Economy (Principle 2) [4]

Objective: To directly functionalize complex molecules at advanced stages of synthesis, avoiding lengthy de novo synthetic routes.

Detailed Protocol:

- Substrate Preparation: Dissolve the advanced intermediate or drug-like molecule (0.05-0.2 mmol) in a suitable green solvent (e.g., acetone, DMSO, or acetonitrile, 1-3 mL).

- Reagent Selection: Add the functionalizing reagent (1.0-2.0 equiv) and any required catalyst (typically 5-10 mol%). Common transformations include C-H borylation, C-H oxidation, or cross-coupling reactions.

- Reaction Conditions: Stir the reaction mixture at optimal temperature (often 25-80°C) under air or inert atmosphere as required. Monitor reaction progress carefully to prevent over-functionalization.

- Analytical Monitoring: Use UPLC-MS or HPLC to track conversion and detect regioisomers. High-throughput experimentation platforms can screen multiple conditions in parallel when reaction selectivity is challenging.

- Purification: Isolate the functionalized product using preparative HPLC or flash chromatography.

- Characterization: Confirm structure and regiochemistry using comprehensive NMR analysis (¹H, ¹³C, 2D techniques) and high-resolution mass spectrometry.

Research Application: Late-stage functionalization allows medicinal chemists to generate diverse analogs from common intermediates, significantly reducing synthetic steps and resource consumption [4]. This approach has been used to create over 50 different drug-like molecules at AstraZeneca and has enabled the efficient synthesis of complex PROTACs (PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras) in just a single step [4].

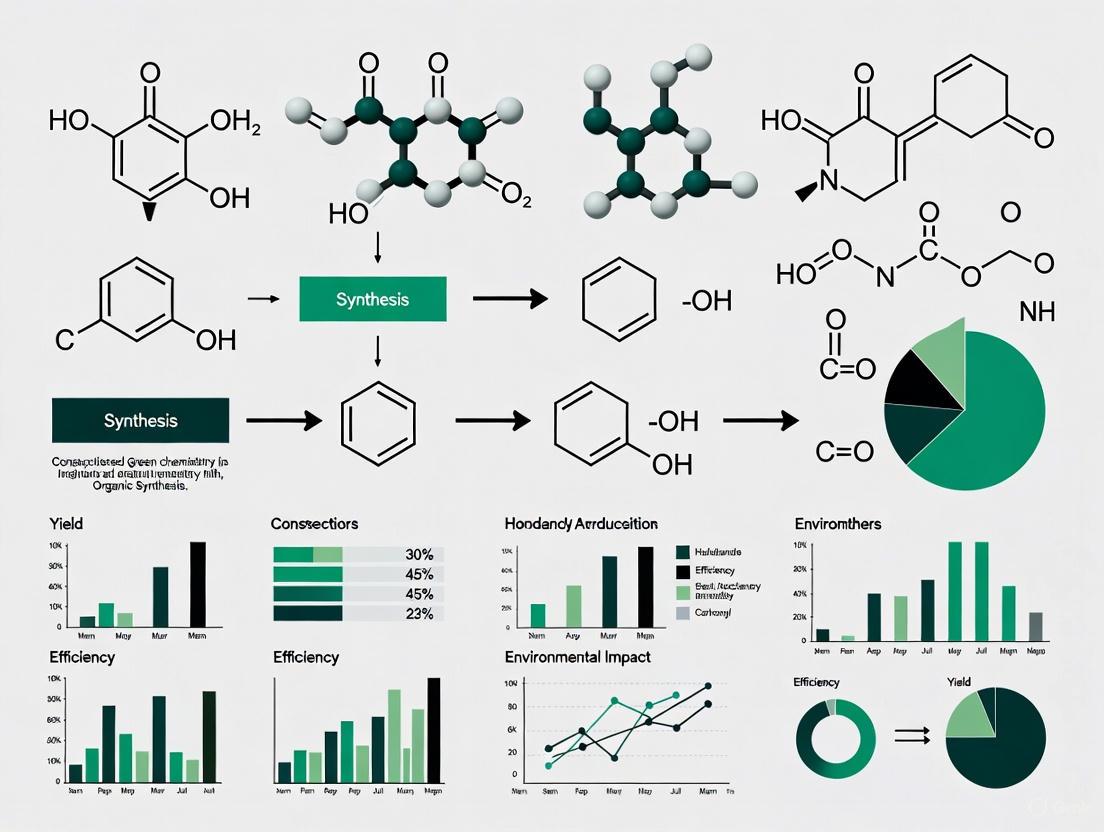

Visualization of Green Chemistry Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate key experimental setups and strategic approaches in green chemistry synthesis, providing visual guidance for implementation in research laboratories.

Diagram 1: Green Chemistry Experimental Approaches and Principles Mapping. This workflow illustrates how different green chemistry methodologies align with and fulfill specific principles of green chemistry.

Research Reagent Solutions for Green Synthesis

The implementation of green chemistry principles requires specific reagents and catalysts designed to enhance sustainability while maintaining synthetic efficiency. The following table details key research reagents that enable greener synthetic transformations.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Green Chemistry Synthesis

| Reagent/Catalyst | Function | Green Advantage | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickel Catalysts | Replacement for precious metals in cross-coupling [4] | More abundant, lower cost, reduced environmental impact [4] | Borylation and Suzuki reactions [4] |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Biodegradable solvent systems [7] | Low toxicity, renewable feedstocks, customizable properties [7] | Extraction of metals from e-waste [7] |

| Visible Light Photocatalysts | Light-absorbing catalysts (e.g., Ru(bpy)₃²⁺, organic dyes) [4] | Energy efficiency, mild conditions, replaces harsh reagents [4] | C-H functionalization, radical reactions [4] |

| Biocatalysts (Enzymes) | Protein catalysts for specific transformations [4] | High selectivity, aqueous conditions, biodegradable [4] | Asymmetric synthesis, protecting group-free routes [4] |

| Iron Nitride (FeN) | Permanent magnet material [7] | Replaces rare-earth elements, earth-abundant components [7] | Sustainable electronics, motors [7] |

| Silver Nanoparticles (Green Synthesis) | Catalytic and antimicrobial agent [3] | Plant-derived synthesis replaces toxic chemical reductants [3] | Biomedical applications, catalysis [3] |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of Green Chemistry continues to evolve through technological innovations that enhance synthetic efficiency and sustainability. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are revolutionizing reaction optimization and design, enabling researchers to predict reaction outcomes, identify greener synthetic pathways, and optimize conditions with minimal experimental effort [7] [4] [8]. Machine learning models can forecast where a particular chemical reaction will occur within complex molecules, outperforming previous methods and streamlining drug development while simultaneously contributing to environmental sustainability [4]. The integration of AI with high-throughput experimentation allows researchers to explore thousands of reaction conditions using minimal material, dramatically improving the efficiency of reaction discovery and optimization [4].

Advanced solvent systems represent another frontier in green synthesis. Deep eutectic solvents (DES), composed of mixtures of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, offer customizable, biodegradable alternatives to conventional organic solvents [7]. These systems align with circular economy goals by enabling resource recovery from e-waste, spent batteries, and biomass while minimizing emissions and chemical waste [7]. Similarly, water-based reactions continue to gain prominence, with research demonstrating that many transformations can be achieved in or on water, leveraging its unique properties to facilitate or accelerate chemical processes even with water-insoluble reactants [7]. This represents a paradigm shift from traditional assumptions that water was incompatible with many catalytic processes.

The future of Green Chemistry will increasingly focus on systems thinking and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) approaches that evaluate environmental impacts across the entire chemical lifecycle [9]. Recent proposals for twelve fundamental principles for LCA of chemicals aim to support practitioners in adopting this methodology to guide and enhance research [9]. This holistic perspective ensures that green chemistry innovations deliver meaningful environmental benefits beyond the laboratory scale, supporting the transition toward a truly sustainable chemical enterprise [9].

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry provide a comprehensive framework for developing synthetic methodologies that align with environmental sustainability goals without compromising scientific rigor or efficiency. For researchers and drug development professionals, integrating these principles into daily practice requires both a philosophical shift toward prevention-based design and the adoption of specific technical approaches including mechanochemistry, photocatalysis, late-stage functionalization, and aqueous reaction media. The quantitative metrics and experimental protocols outlined in this whitepaper offer practical tools for implementation, while emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and novel solvent systems promise to further enhance the green credentials of chemical synthesis.

As the field advances, the integration of Green Chemistry principles with broader sustainability frameworks like Life Cycle Assessment will ensure that molecular design and synthetic strategy decisions consider impacts across the chemical lifecycle. This systematic approach, combined with ongoing innovation in catalysts, reagents, and reaction platforms, will enable the chemical research community to address pressing global challenges while continuing to deliver the molecular innovations that underpin modern society. The widespread adoption of these principles represents not merely a technical adjustment but a fundamental evolution in how chemistry is practiced, offering a pathway to reconcile chemical innovation with environmental responsibility.

Defining Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) and Its Role in Sustainable Development

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) represents a transformative approach to analytical science that integrates the principles of green chemistry into analytical methodologies, aiming to reduce the environmental and human health impacts traditionally associated with chemical analysis [10]. As a specialized subfield, GAC focuses on the optimization of analytical processes to ensure they are safe, nontoxic, environmentally friendly, and efficient in their use of materials, energy, and waste generation [11]. This paradigm shift aligns analytical chemistry with sustainability science, addressing concerns about the field's historical reliance on energy-intensive processes, non-renewable resources, and waste generation [12].

The emergence of GAC responds to the recognition that traditional analytical methods have often relied on toxic reagents and solvents, generating significant waste and posing potential risks to both analysts and the environment [11]. In an era of increasing environmental awareness, GAC provides a framework for mitigating the adverse effects of analytical activities on human safety, human health, and the environment while maintaining high standards of accuracy and precision [13]. This approach is particularly relevant given that analytical chemistry's success in determining the composition and quantity of matter plays a crucial role in addressing environmental challenges, despite its own environmental footprint [12].

Principles and Framework of GAC

The Foundation of GAC Principles

The foundation of GAC lies in the 12 principles of green chemistry, which provide a comprehensive framework for designing and implementing environmentally benign analytical techniques [10]. These principles emphasize waste prevention, the use of renewable feedstocks, energy efficiency, atom economy, and the avoidance of hazardous substances, all central to reimagining the role of analytical chemistry in today's environmental and industrial landscape [10]. When specifically applied to analytical chemistry, these principles have been adapted to form the 12 principles of GAC, which prioritize various aspects of analytical methods including direct analytical techniques, minimal sample processing, and safety for operators and the environment [13].

The 12 principles of GAC provide crucial guidelines for implementing greener practices in corresponding analytical procedures and can be represented by the mnemonic "SIGNIFICANCE" [13]. These principles collectively guide the development of methodologies that are both effective and environmentally friendly, serving as a roadmap for integrating GAC into diverse applications [10]. For instance, the principle of atom economy advocates for the optimization of chemical reactions to ensure maximum incorporation of starting materials into final products, thereby reducing waste, while the emphasis on safer solvents and auxiliaries has driven the exploration of alternative extraction and separation techniques [10].

Relationship Between GAC and Sustainable Development

While the terms "sustainability" and "greenness" are often used interchangeably, they represent distinct concepts. Sustainable development balances three interconnected pillars: economic, social, and environmental, whereas the philosophy of GAC deals primarily with the environmental dimension [14]. Sustainability is not just about efficiently using resources and reducing waste; it also encompasses ensuring economic stability and fostering social well-being [12].

For analytical chemistry to be described as sustainable, it should consider the three pillars for sustainable development—environmental, economic, and social aspects [14]. This distinction is crucial because GAC primarily focuses on environmental impacts, while sustainable analytical chemistry embraces a broader perspective that includes economic viability and social responsibility. The correct application of GAC provides many benefits that extend beyond environmental protection to include improved safety for analysts and potential economic advantages through reduced resource consumption [14].

The relationship between GAC and sustainable development can be visualized through the following conceptual framework:

Figure 1: Relationship between GAC and Sustainable Development

Core Methodologies and Green Metrics

Green Methodologies in Analytical Chemistry

GAC embraces a range of innovative methodologies that transform analytical workflows to reduce environmental impact. Key approaches include the incorporation of green solvents, such as water, ionic liquids, bio-based alternatives, and supercritical carbon dioxide, which replace volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and reduce toxicity [10]. Additionally, GAC utilizes energy-efficient techniques like microwave-assisted and ultrasound-assisted methodologies to enhance reaction rates and reduce the energy demands of analytical processes [10]. These innovations not only lower operational costs but also contribute to the broader goals of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and mitigating climate change [10].

Miniaturization and automation represent another significant strategy in GAC. Miniaturized systems minimize sample size as well as solvent and reagent consumption, while automated systems save time, lower the consumption of reagents and solvents, and consequently reduce waste generation [12]. Automation also minimizes human intervention, significantly lowering the risks of handling errors, operator exposure to hazardous chemicals, and accidents in the laboratory [12]. Furthermore, integrating multiple preparation steps into a single, continuous workflow simplifies operations while cutting down on resource use and waste production [12].

Greenness Assessment Tools

A critical development in GAC is the creation of standardized metrics to evaluate the environmental performance of analytical methods. Numerous greenness assessment tools have been developed to quantify and compare the sustainability of analytical procedures, enabling researchers to make informed decisions about method selection and development [13]. The following table summarizes the key GAC metrics currently in use:

Table 1: Green Analytical Chemistry Assessment Metrics

| Metric Name | Year Introduced | Assessment Basis | Output Format | Key Parameters Evaluated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) | 2002 | Four criteria-based | Pictogram with four quadrants | PBT chemicals, hazardous waste, pH, waste amount [13] |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | 2012 | Penalty point system | Numerical score (100=ideal) | Reagents, energy, hazards, waste [13] |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) | 2018 | Multi-criteria criteria | Color-coded pictogram | Entire method lifecycle [11] [13] |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) | 2020 | 12 principles of GAC | Circular pictogram with score | Comprehensive GAC principles [11] [13] |

| AGREEprep | 2021 | Sample preparation focus | Numerical score (0-1) | Sample preparation-specific parameters [13] [12] |

| BAGI (Blue Applicability Grade Index) | 2022 | Applicability and practicality | Numerical score with color | Method performance, practicality [13] |

These tools vary in their approach and focus, with some providing simple pass/fail evaluations while others offer more nuanced scoring systems. For instance, the AGREE metric provides a holistic evaluation of method greenness based on 12 distinct criteria, helping identify areas for improvement in developing more environmentally friendly analytical procedures [11]. Similarly, the GAPI tool uses a color-coded system to assess the greenness of an analytical method throughout its entire life cycle, from reagents and solvents used to waste management [11].

The application of these assessment tools to standard analytical methods has revealed significant opportunities for improvement. A recent evaluation of 174 standard methods and their 332 sub-method variations from CEN, ISO, and Pharmacopoeias using the AGREEprep metric demonstrated poor greenness performance, with 67% of methods scoring below 0.2 on a 0-1 scale [12]. These findings highlight the urgent need to update standard methods by including contemporary and mature analytical approaches that align with GAC principles.

GAC in Pharmaceutical Research and Organic Synthesis

Integration with Green Synthesis Principles

The pharmaceutical industry has emerged as a key adopter of green chemistry principles, including GAC, driven by both environmental concerns and economic benefits [15]. The industry prioritizes developing sustainable chemistry for drug fabrication and optimizing the environmental sustainability of numerous drugs [15]. Since 2011, the adoption of green chemistry methods has led to a 27% reduction in chemical waste according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), with key strategies including process modifications, elimination of toxic reagents, integration of recyclability, and minimization of synthetic steps [15].

GAC aligns with the broader framework of green synthesis in pharmaceutical development. Green synthesis, also known as sustainable methods or environmentally friendly synthesis, aims to reduce the environmental effect of chemical reactions and processes by minimizing the use of dangerous chemicals, decreasing energy consumption, reducing waste generation, and limiting resource depletion while maximizing efficiency and sustainability [15]. These objectives directly parallel those of GAC, creating natural synergies between analytical and synthetic approaches in pharmaceutical research.

Sustainable Analytical Techniques in Drug Development

The application of GAC principles in pharmaceutical research has led to the development and adoption of various sustainable analytical techniques. These include:

Miniaturized separation techniques that reduce solvent consumption and waste generation while maintaining analytical performance [10].

Alternative extraction methods using green solvents such as water, supercritical fluids, or ionic liquids instead of traditional organic solvents [16] [10].

Energy-efficient detection systems that lower power consumption without compromising sensitivity or accuracy [10].

Direct analysis techniques that eliminate or minimize sample preparation steps, reducing overall resource consumption [13].

These approaches demonstrate that environmental benefits often align with improved efficiency and cost-effectiveness, particularly through reduced reagent consumption and waste disposal requirements. The pharmaceutical industry's experience shows that green chemistry, including GAC, can be both environmentally responsible and economically advantageous [15].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Framework for Implementing GAC

Implementing GAC in research and industrial settings requires a systematic approach that balances analytical performance with environmental considerations. The following workflow provides a structured framework for transitioning from traditional analytical methods to greener alternatives:

Figure 2: GAC Implementation Workflow

The Researcher's Toolkit for GAC

Successful implementation of GAC requires familiarity with a suite of green alternatives to traditional analytical reagents and materials. The following table outlines key research reagent solutions used in green analytical chemistry:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Reagent/Material Category | Traditional Examples | Green Alternatives | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvents | Chloroform, hexane, methanol | Water, supercritical CO₂, ionic liquids, bio-based solvents (e.g., ethyl lactate) | Extraction, separation, mobile phases [16] [10] |

| Sorbents | Synthetic polymers | Bio-based sorbents, molecularly imprinted polymers | Sample preparation, extraction [10] |

| Catalysts | Heavy metal catalysts | Biocatalysts, metal-free catalysts, heterogeneous catalysts | Reaction facilitation, derivatization [16] [15] |

| Energy Sources | Conventional heating | Microwave, ultrasound, photo-induced processes | Sample preparation, reaction acceleration [10] |

| Analytical Scales | Full-scale apparatus | Miniaturized systems, microextraction devices | All analytical steps [10] [12] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Green Sample Preparation

The following protocol illustrates the application of GAC principles to sample preparation, a particularly resource-intensive stage of analysis:

Objective: Implement a green sample preparation method for the analysis of organic compounds in aqueous samples.

Principles Applied:

- Directly address the 3rd GAC principle: "Use minimal sample size and generate minimal waste" [13]

- Incorporate the green sample preparation (GSP) principles of miniaturization and integration [12]

Procedure:

Sample Collection and Preservation:

- Collect water samples in 40 mL amber glass vials with PTFE-lined caps

- Minimize preservative use; if necessary, use minimal amounts of biodegradable preservatives

- Store at 4°C until analysis (max 7 days)

Miniaturized Extraction:

- Utilize solid-phase microextraction (SPME) or liquid-phase microextraction (LPME) instead of traditional liquid-liquid extraction

- For SPME: immerse fiber in 10 mL sample for 30-60 minutes with agitation

- For LPME: use 1-10 μL of organic acceptor phase suspended in the sample

- Apply energy-assisted extraction (vortex, ultrasound, or microwave) to reduce extraction time

Analysis:

- Use minimal sample injection volumes (1 μL or less for liquid chromatography)

- Employ microbore or capillary columns to reduce mobile phase consumption

- Optimize for short run times without compromising separation efficiency

Waste Management:

- Collect all waste separately for proper disposal or recycling

- Implement solvent recycling systems where feasible

- Neutralize acidic/basic waste before disposal

Greenness Assessment:

- Calculate Analytical Method Volume Intensity (AMVI) [11]

- Evaluate method using AGREEprep metric, targeting score >0.7 [12]

- Compare solvent consumption and energy use with traditional methods

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Current Barriers to GAC Implementation

Despite significant advancements, several substantial challenges hinder the widespread adoption of GAC. Analytical chemistry largely operates under a weak sustainability model that assumes natural resources can be consumed and waste generated as long as technological progress and economic growth compensate for the environmental damage [12]. Transitioning to a strong sustainability model would require acknowledging ecological limits and planetary boundaries, emphasizing practices aimed at restoring and regenerating natural capital [12].

Additional barriers include:

- Coordination failures within the field, with limited cooperation between key players like industry and academia [12]

- Resistance to change in established practices, particularly in regulated industries where method validation is rigorous and time-consuming [10]

- Lack of clear direction toward greener practices, with continued strong focus on analytical performance over sustainability factors [12]

- The rebound effect, where environmental benefits of greener methods are offset by increased usage due to lower costs or greater accessibility [12]

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The future of GAC looks promising, with several emerging technologies offering new ways to optimize workflows, minimize waste, and streamline analytical processes [10]. Key future directions include:

Integration of artificial intelligence and digital tools to optimize method development and reduce experimental waste [10]

Advanced green materials including novel bio-based solvents and recyclable sorbents [10]

Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC) frameworks that focus on minimizing waste and keeping materials in use for as long as possible [12]

Strong sustainability approaches that prioritize nature conservation and ecological restoration in analytical practice [12]

Improved standardization with regulatory agencies increasingly incorporating green metrics into method validation and approval processes [12]

The successful future development of GAC will require collaborative efforts across industry, academia, and regulatory bodies to bridge innovation gaps and accelerate the adoption of sustainable practices [12]. As the global community intensifies its efforts to address environmental challenges, GAC will continue to expand its role in offering practical solutions to balance analytical needs with ecological preservation [10].

The Environmental and Economic Drivers for Adopting Green Practices in the Pharmaceutical Industry

The pharmaceutical industry stands at a pivotal juncture, facing increasing pressure to transform its traditional manufacturing processes into more sustainable and environmentally responsible operations. The adoption of green chemistry principles represents a fundamental shift in how pharmaceutical companies approach drug design, synthesis, and production, moving beyond mere regulatory compliance to embrace sustainability as a core business strategy. This transformation is driven by a powerful combination of environmental imperatives and economic considerations that are reshaping the industry landscape. Within the context of organic synthesis research, green chemistry provides a framework for developing synthetic methodologies that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances, thereby minimizing the environmental footprint of pharmaceutical manufacturing while maintaining scientific rigor and efficiency [17]. The industry's significant environmental impact—responsible for 17% of global carbon emissions with half deriving from active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs)—underscores the urgent need for this paradigm shift [18]. This technical guide examines the key drivers, practical methodologies, and implementation frameworks for adopting green chemistry principles in pharmaceutical research and development, providing drug development professionals with actionable strategies for advancing sustainable medicinal chemistry.

Environmental Drivers

Regulatory Frameworks and Policies

Stringent environmental regulations and international agreements are compelling pharmaceutical companies to fundamentally redesign their chemical processes and manufacturing operations. These regulatory drivers are increasingly shaping research priorities and process development in organic synthesis.

European Green Deal: This comprehensive policy initiative aims to achieve carbon neutrality across the European Union by 2050, pushing pharmaceutical companies to decarbonize their operations through green chemistry innovations. The deal affects packaging requirements and mandates greater transparency regarding ecosystem impacts, with Extended Producer Responsibilities requiring pharmaceutical producers to cover 80% of the costs to remove micropollutants from wastewater [18].

REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals): This regulatory framework protects human health and the environment from hazardous substances by ensuring safer chemical utilization throughout the pharmaceutical supply chain [18].

Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD): Effective from 2024, this EU directive requires detailed reporting on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) efforts, including carbon footprint, natural resource consumption, and social policies. This makes corporate responsibility not only measurable but legally enforceable [19].

European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS): These standards, introduced alongside CSRD, provide a structured framework for companies to disclose sustainability efforts addressing climate change, pollution, and biodiversity impacts [19].

Regulation on Setting Ecodesign Requirements (ESPR): This regulation pushes manufacturers toward producing more durable and environmentally friendly products, requiring pharmaceutical companies to consider sustainability from the initial design stage rather than as an afterthought [19].

Environmental Impact Reduction

The implementation of green chemistry principles directly addresses the pharmaceutical industry's substantial environmental footprint through measurable reductions in waste generation, energy consumption, and resource utilization.

Table 1: Environmental Impact Metrics in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

| Environmental Parameter | Traditional Process Impact | Green Chemistry Solutions | Potential Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| API-related Waste | 10 billion kg waste generated annually from 65-100 million kg APIs [18] | Continuous flow synthesis, solvent substitution | Up to 80% waste reduction |

| Carbon Emissions | 17% of global carbon emissions, 50% from APIs [18] | Renewable energy, energy-efficient processes | 55-100% reduction targets |

| Solvent Usage | High volumes of hazardous solvents | Green solvents (water, bio-based, ionic liquids) | 60-95% reduction |

| Energy Consumption | Energy-intensive batch processes | Microwave-assisted synthesis, process intensification | 50-70% energy savings |

| Water Consumption | Significant water footprint in manufacturing | Water recycling, closed-loop systems | Zero water waste targets |

The industry's transition toward green chemistry is evidenced by the fact that 75% of pharmaceutical brands have reshaped their business models to account for Climate Scenario Analyses, helping them assess risks and create more resilient sustainability strategies [18]. This fundamental reengineering of business operations demonstrates the profound impact of environmental drivers on corporate strategy.

Economic Drivers

Market Growth and Financial Incentives

The business case for adopting green chemistry in the pharmaceutical industry has strengthened considerably, driven by market forces, investor preferences, and tangible economic benefits that extend beyond mere regulatory compliance.

The green chemistry pharma market is experiencing robust growth, projected to increase at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10%, with the market size expected to reach USD 35 Billion by 2033, up from USD 16.5 Billion in 2024 [20]. This growth significantly outpaces many traditional pharmaceutical sectors, reflecting strong market demand for sustainable alternatives. Several key economic factors are accelerating this transition:

Investor Pressure and ESG Criteria: Pharmaceutical companies face increasing pressure from investors to integrate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria into their core business strategies. This alignment with investor values not only improves access to capital but also enhances long-term shareholder value [21] [19].

Consumer Demand for Sustainability: Growing consumer awareness and preference for environmentally responsible products are influencing pharmaceutical purchasing decisions, creating competitive advantages for companies that embrace green chemistry principles [20].

Regulatory Incentives: The European Green Deal and related frameworks promote green pharmaceuticals through tax credits, grants, and streamlined approvals for sustainability adoption, providing direct financial benefits for compliant companies [18].

Operational Efficiency: Green chemistry principles enable more efficient manufacturing processes, reducing raw material consumption, energy usage, and waste disposal costs. For instance, microwave-assisted synthesis enables chemical reactions within minutes through electromagnetic radiation, helping pharmaceutical producers save both time and energy [18].

Corporate Sustainability Initiatives

Leading pharmaceutical companies are implementing comprehensive sustainability programs that demonstrate the economic viability of green chemistry while delivering substantial environmental benefits.

Table 2: Economic and Environmental Targets of Leading Pharmaceutical Companies

| Company | Sustainability Initiatives | Economic Benefits | Environmental Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novo Nordisk | Circular for Zero initiative, renewable energy adoption | Investment of $158M to modernize insulin production with sustainable projects [22] | Zero environmental impact by 2045; Aligned with SBTi [22] |

| Eisai Co Ltd | Carbon neutrality in Japanese operations, green building designs | Carbon productivity of $159,088 reflecting efficient economic output [22] | 55% reduction in Scope 1 & 2 emissions by 2030; Net-zero by 2050 [22] |

| Johnson & Johnson | Renewable energy transition | 100% renewable energy across all manufacturing sites by 2025 [21] | |

| AstraZeneca | Ambition Zero Carbon program, low-carbon inhaler propellants | 90% reduction in inhaler portfolio carbon footprint by 2030 [22] | |

| Sanofi | Zero water waste initiatives, advanced water recycling systems | Strengthened health systems in low-income countries [21] [22] | |

| Amgen | Sustainable manufacturing optimization | 70% carbon emissions reduction by 2030 [21] | |

| Novartis | Net-zero carbon commitment across global operations | Supply chain sustainability emphasis [21] |

The economic advantages of these initiatives extend beyond direct cost savings to include enhanced brand reputation, competitive differentiation, and resilience against future regulatory changes. As noted by industry leaders, ESG has become central to corporate strategy, critical for delivering long-term value to stakeholders [21].

Green Chemistry Principles in Organic Synthesis

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The practical implementation of green chemistry principles in organic synthesis requires innovative approaches that redefine traditional synthetic methodologies. Below are detailed experimental protocols demonstrating the application of green chemistry in pharmaceutical research.

Metal-Free Oxidative Coupling for 2-Aminobenzoxazoles

Traditional Approach: The conventional method employs Cu(OAc)₂ and K₂CO₃ to catalyze the reaction between o-aminophenol and benzonitrile, yielding approximately 75%. The reagents in this method pose significant hazards to skin, eyes, and respiratory systems [17].

Green Protocol:

- Reaction Setup: Combine benzoxazole (1.0 mmol), amine (1.2 mmol), and tetrabutylammonium iodide (TBAI, 20 mol%) in a suitable reaction vessel.

- Oxidant Addition: Add aqueous tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP, 2.0 mmol) as a green oxidant.

- Reaction Conditions: Heat the mixture to 80°C with continuous stirring for 4-6 hours.

- Reaction Monitoring: Monitor reaction progress by TLC or LC-MS until completion.

- Work-up Procedure: Dilute the reaction mixture with ethyl acetate (15 mL) and wash with brine solution (2 × 10 mL).

- Purification: Separate the organic layer, dry over anhydrous Na₂SO₄, and concentrate under reduced pressure. Purify the crude product by column chromatography on silica gel [17].

Key Advantages: This metal-free approach eliminates transition metal toxicity and cost concerns while maintaining high efficiency. The method employs more environmentally benign reagents and demonstrates the feasibility of metal-free C-H activation for C-N bond formation.

Green Synthesis of Isoeugenol Methyl Ether (IEME) from Eugenol

Traditional Approach: Conventional O-methylation uses highly toxic dimethyl sulfate or methyl halides with strong bases like KOH or NaOH at elevated temperatures, yielding approximately 83% with significant environmental hazards [17].

Green Protocol:

- Reactor Setup: Charge a round-bottom flask with eugenol (1.0 mmol), dimethyl carbonate (DMC, 4.0 mmol) as a green methylating agent, and polyethylene glycol (PEG, 0.1 mmol) as a phase-transfer catalyst.

- DMC Addition: Maintain a controlled DMC drip rate of 0.09 mL/min to ensure efficient reaction.

- Reaction Conditions: Heat the reaction mixture to 160°C with continuous stirring for 3 hours.

- Reaction Monitoring: Analyze reaction progress by GC-MS or TLC at regular intervals.

- Product Isolation: After completion, cool the reaction mixture to room temperature and extract with diethyl ether (3 × 15 mL).

- Purification: Combine the organic extracts, wash with water, dry over anhydrous MgSO₄, and concentrate under reduced pressure to obtain the pure product [17].

Key Advantages: This method achieves a higher yield of 94% while replacing hazardous methylating agents with dimethyl carbonate, which serves as a non-toxic solvent and environmentally benign reagent. The process demonstrates simultaneous O-methylation and allylbenzene isomerization in a single pot, reducing steps and waste generation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Green Reagent Solutions

The implementation of green chemistry in pharmaceutical research requires a specialized set of reagents and solvents that reduce environmental impact while maintaining synthetic efficiency.

Table 3: Essential Green Research Reagents for Organic Synthesis

| Reagent/Solvent | Function in Synthesis | Traditional Alternative | Environmental & Efficiency Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl Carbonate (DMC) | Green methylating agent | Dimethyl sulfate, methyl halides | Biodegradable, non-toxic, versatile reagent [17] |

| Ionic Liquids (e.g., [BPy]I) | Reaction medium and catalyst | Volatile organic solvents | Negligible vapor pressure, recyclable, high thermal stability [17] |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Phase-transfer catalyst and solvent | Organic solvents, quaternary ammonium salts | Non-toxic, biodegradable, recyclable [17] |

| Water | Green solvent | Organic solvents (THF, DCM, DMF) | Non-toxic, non-flammable, inexpensive [17] |

| Bio-based Solvents (eucalyptol, ethyl lactate) | Sustainable reaction media | Petroleum-derived solvents | Renewable feedstocks, reduced carbon footprint [17] |

| tert-Butyl Hydroperoxide (TBHP) | Green oxidant | Metal-based oxidants | Reduced metal contamination, water as byproduct [17] |

| Pineapple Juice, Onion Peel | Natural catalysts | Mineral acids, metal catalysts | Renewable, biodegradable, non-hazardous [17] |

| Microwave Irradiation | Energy transfer method | Conventional heating | Rapid heating, reduced reaction times, energy savings [18] [17] |

Implementation Framework

Technological Enablers and Workflow Integration

The successful implementation of green chemistry principles in pharmaceutical research and development requires both technological innovations and systematic workflow integration. Advanced technologies play a crucial role in enabling greener synthetic methodologies and process optimization.

Continuous Flow Synthesis: This technology utilizes specialized equipment to improve management and optimization of reactions in pharmaceutical production. Unlike traditional batch processes, continuous flow systems offer enhanced heat and mass transfer, improved safety profiles, and better control over reaction parameters, leading to reduced waste generation and higher efficiency [18].

Microwave-Assisted Synthesis: This approach enables chemical reactions within minutes through electromagnetic radiation, ionic conduction, and dipole polarization, helping pharmaceutical producers save significant time and energy compared to conventional heating methods [18] [17].

AI and Machine Learning Solutions: The deployment of computational tools in green chemistry helps synthesize large datasets, reduce human error, and predict reaction conditions, further accelerating innovation and utilizing sustainable manufacturing practices. These tools guide the design of sustainable chemical processes through predictive modeling of reagent toxicity, reaction efficiency, and environmental impact [18] [23].

Analytical Techniques: Green chromatography, spectroscopy, and bioassays minimize and eliminate chemical toxicity in laboratories, providing analytical support for sustainable process development [18].

The integration of these technologies into pharmaceutical research workflows can be visualized through the following conceptual framework:

Strategic Implementation Roadmap

A phased approach to implementing green chemistry principles ensures systematic integration into pharmaceutical research and development organizations:

Phase 1: Assessment and Baseline Establishment

- Conduct a comprehensive audit of current synthetic methodologies and environmental impact metrics

- Establish baseline measurements for Process Mass Intensity (PMI), E-factor, and carbon footprint

- Identify high-impact opportunities for green chemistry implementation

- Develop organizational capability through targeted training programs

Phase 2: Technology Integration and Process Redesign

- Incorporate green chemistry principles into early-stage drug design and development

- Implement computational tools for toxicity prediction and solvent selection

- Establish dedicated resources for green chemistry research and development

- Develop standardized green chemistry evaluation criteria for project advancement

Phase 3: Continuous Improvement and Culture Embedding

- Foster cross-functional collaboration between chemistry, engineering, and environmental health and safety teams

- Establish key performance indicators (KPIs) for green chemistry implementation

- Create recognition systems for successful green chemistry innovations

- Develop supplier engagement programs to extend green principles across the value chain

The implementation of this framework enables pharmaceutical companies to systematically reduce their environmental impact while realizing significant economic benefits. As noted in industry assessments, sustainability is no longer just an industry buzzword but a fundamental business strategy that pharmaceutical companies must embrace to remain competitive [19].

The adoption of green practices in the pharmaceutical industry represents a strategic imperative driven by powerful environmental and economic factors. Regulatory pressures, resource constraints, and stakeholder expectations are compelling companies to fundamentally rethink their approach to drug design, synthesis, and manufacturing. The principles of green chemistry provide a robust framework for developing synthetic methodologies that reduce environmental impact while maintaining scientific excellence and economic viability. The experimental protocols and implementation strategies outlined in this technical guide demonstrate that sustainability and innovation are not mutually exclusive but rather complementary objectives that can drive long-term competitive advantage. As the industry continues to evolve, the integration of green chemistry principles into organic synthesis research will be essential for creating a more sustainable, efficient, and socially responsible pharmaceutical sector. The companies that successfully embrace this transformation will not only mitigate environmental risks but also position themselves as leaders in the next era of pharmaceutical innovation.

Traditional organic synthesis has long relied on hazardous reagents and solvents, a practice deeply embedded in the history of chemical research and industrial production. These substances, while effective for their intended chemical transformations, carry significant liabilities. They pose risks to researcher safety through potential explosions, fires, and acute or chronic health effects [24] [25]. Environmental impacts extend from fugitive emissions contributing to air pollution to hazardous waste streams that require energy-intensive treatment and disposal [24] [26]. From a practical perspective, they necessitate extensive engineering controls, specialized personal protective equipment, and complex waste management protocols, increasing the cost and complexity of research and development [25] [26].

This paper frames these limitations within the broader thesis of Green Chemistry, a proactive approach that designs chemical products and processes to reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances [24]. Green chemistry is not merely a disposal problem; it is a fundamental philosophy of pollution prevention at the molecular level [24]. For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting this framework is not just an environmental imperative but a strategy for achieving more efficient, economical, and sustainable synthetic pathways. By examining the hazards of traditional substances, the principles that guide their replacement, and the practical alternatives available, this whitepaper provides a technical roadmap for advancing organic synthesis beyond its traditional constraints.

The Green Chemistry Framework: Principles for Modern Synthesis

The foundational framework for moving beyond hazardous materials is articulated in the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry, developed by Paul Anastas and John Warner [27]. These principles provide a systematic guide for designing safer, more efficient chemical processes. Several principles are directly relevant to overcoming the limitations of hazardous reagents and solvents:

- Prevention: It is better to prevent waste than to treat or clean up waste after it is formed [27]. This cornerstone principle emphasizes that avoiding the use of hazardous substances eliminates the associated waste streams entirely.

- Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses: Synthetic methods should be designed to use and generate substances that possess little or no toxicity to human health and the environment [27]. This directly challenges the tradition of using highly reactive and toxic reagents.

- Designing Safer Chemicals: Chemical products should be designed to preserve efficacy of function while reducing toxicity [27]. This involves understanding structure-activity relationships to minimize hazard while maintaining performance.

- Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries: The use of auxiliary substances (e.g., solvents, separation agents) should be made unnecessary wherever possible and, when used, innocuous [25] [27].

- Design for Energy Efficiency: Energy requirements should be recognized for their environmental and economic impacts and should be minimized. Synthetic methods should be conducted at ambient temperature and pressure [24].

- Use of Renewable Feedstocks: A raw material or feedstock should be renewable rather than depleting whenever technically and economically practicable [24] [28].

- Use of Catalysts, not Stoichiometric Reagents: Catalytic reagents (as selective as possible) are superior to stoichiometric reagents [24]. Catalysts minimize waste by carrying out a single reaction many times.

- Real-time Analysis for Pollution Prevention: Analytical methodologies need to be further developed to allow for real-time, in-process monitoring and control prior to the formation of hazardous substances [24].

These principles shift the focus from remediation—dealing with hazards after they are created—to inherent safety through intelligent design [24]. This philosophical and practical shift is critical for the future of sustainable drug development and organic research.

Quantitative Analysis of Hazardous Solvents and Safer Alternatives

The choice of solvent is a critical parameter in reaction design, impacting yield, selectivity, workup, and the overall environmental and safety profile of a process. Quantitative metrics such as Flash Point (a measure of flammability) and Threshold Limit Value (TLV) (a measure of occupational exposure limits) provide a basis for comparing solvents objectively [25].

Table 1: Common Hazardous Solvents, Their Issues, and Safer Replacements

| Solvent | Flash Point (°C) | TLV (ppm) | Key Hazards & Issues | Recommended Replacements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diethyl Ether | -40 | 400 | Extremely low flash point, peroxide former [25] | tert-Butyl methyl ether, 2-MeTHF [25] |

| n-Hexane | -23 | 50 | Reproductive toxicant, more toxic than alternatives [25] | Heptane [25] |

| Dichloromethane (DCM) | N/A | 100 | Hazardous airborne pollutant, carcinogen [25] | Ethyl acetate/heptane mixtures, Ethyl acetate/ethanol mixtures [25] |

| Benzene | -11 | 0.5 | Carcinogen, reproductive toxicant [25] | Toluene [25] |

| N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) | 86 | Data not determined | Toxic [25] | Acetonitrile, Cyrene, γ-Valerolactone (GVL) [25] |

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) | 57 | 10 | Hazardous airborne pollutant, toxic, carcinogen [25] | Acetonitrile, Cyrene, γ-Valerolactone (GVL) [25] |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | -21.2 | 50 | Peroxide former [25] | 2-MeTHF [25] |

| 1,4-Dioxane | 12 | 20 | Carcinogen, peroxide former [25] | tert-Butyl methyl ether, 2-MeTHF [25] |

| Chloroform | N/A | 10 | Hazardous airborne pollutant, carcinogen [25] | Dichloromethane (though still hazardous, a lesser evil) [25] |

The data in Table 1, adapted from studies by Pfizer Global R&D and others, demonstrates a clear strategy for solvent substitution [25]. For example, replacing the highly flammable diethyl ether with 2-MeTHF (2-Methyltetrahydrofuran) mitigates peroxide formation risks. Similarly, substituting the neurotoxic n-hexane with heptane provides similar solvent properties with a significantly improved safety profile [25]. A particularly impactful substitution is replacing dichloromethane (DCM), a common carcinogen used in chromatography and extractions, with ethyl acetate and alcohol mixtures, which can achieve similar eluting strengths without the high toxicity [25].

The Rise of Bio-Based and Novel Green Solvents

Beyond direct substitutions, a new class of solvents derived from renewable biomass is gaining traction, aligning with the principle of using renewable feedstocks [24] [28].

- Cyrene (dihydrolevoglucosenone): Derived from cellulose, it is a promising, safe, and sustainable dipolar aprotic solvent alternative to DMF and NMP [25].

- 2-MeTHF: Derived from furfural (from biomass), it is a commercially available ether solvent with excellent properties for replacing THF and diethyl ether [25].

- Limonene: A hydrocarbon solvent obtained from citrus fruit peels, it can replace petroleum-based hydrocarbons like hexane in certain applications [28].

- Ethanol and 1-Butanol: These common solvents are widely available in bio-renewable forms, produced from fermentation rather than petroleum cracking, which avoids generating harmful byproducts like benzene [25].

Other innovative solvent systems include:

- Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) and Ionic Liquids: These designer solvents offer low volatility and can be tailored for specific applications, though their full green credentials require lifecycle assessment [28].

- Subcritical Water and Supercritical Fluids (e.g., CO₂): Using water under pressure and temperature or supercritical CO₂ can eliminate organic solvents entirely in some processes, such as extraction and chromatography [28].

Experimental Protocols: Implementing Green Solvent Strategies

Protocol: Green Extraction using 2-MeTHF

This protocol outlines the replacement of dichloromethane (DCM) or diethyl ether in a liquid-liquid extraction.

- Objective: To separate an organic compound from an aqueous reaction mixture using a safer solvent.

- Traditional Method: The reaction mixture is diluted with water and extracted with 3 x 50 mL portions of DCM. The combined organic layers are dried (MgSO₄) and concentrated under reduced pressure.

- Green Method:

- Reagent Solution: After the reaction is complete, dilute the mixture with a saturated NaCl solution (brine) to reduce emulsion formation.

- Extraction: Add an equal volume of 2-MeTHF to the separatory funnel and shake vigorously. Vent periodically as 2-MeTHF can build pressure.

- Phase Separation: Allow the layers to separate. 2-MeTHF has limited water solubility (~5g/100mL) and typically forms a distinct upper layer.

- Repeat: Perform the extraction 2-3 times with fresh 2-MeTHF.

- Drying and Concentration: Combine the 2-MeTHF layers and dry over a suitable drying agent (e.g., MgSO₄ or Na₂SO₄). Remove the solvent under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator. 2-MeTHF has a boiling point of 78-80°C, making it easy to remove.

- Key Considerations:

- Performance: 2-MeTHF has similar solvation properties to THF and DCM for many organic compounds.

- Safety Advantage: It has a higher flash point (11°C) than diethyl ether (-40°C) and THF (-21°C) and does not form peroxides upon standing, unlike ethers such as diethyl ether and THF [25].

- Sustainability: It is derived from renewable resources like levulinic acid [25].

Protocol: Green Chromatography using Ethyl Acetate/Ethanol Mixtures

This protocol describes replacing DCM-based mobile phases in normal-phase flash chromatography.

- Objective: To purify a crude reaction mixture using a greener solvent system.

- Traditional Method: A gradient of DCM and methanol, or hexane and ethyl acetate, is used.

- Green Method:

- Solvent System Selection: Replace the DCM/MeOH or hexane/EtOAc system with a Heptane/Ethyl Acetate/EtOH system.

- Eluting Strength Calibration: The eluting strength of DCM (ε⁰ = 0.40) can be approximated by a mixture of Heptane, Ethyl Acetate, and a small percentage of Ethanol. For instance, a 5-10% ethanol in ethyl acetate mixture can be used to adjust polarity as needed. Sigma-Aldrich provides detailed guides on matching eluting strengths [25].

- Method Development: Start with a high ratio of heptane to ethyl acetate/ethanol and gradually increase the polarity. Monitor separation by TLC.

- Execution: Run the flash column with the optimized heptane/ethyl acetate/ethanol gradient.

- Key Considerations:

- Performance: This system can achieve separations comparable to DCM-based methods without the associated toxicity [25]. Yabre et al. (2018) have demonstrated that solvents like ethanol and acetone can replace methanol and acetonitrile in reversed-phase liquid chromatography without major compromises [25].

- Safety Advantage: Eliminates the use of DCM, a suspected carcinogen, and hexane, a neurotoxin [25].

- Waste Management: The waste stream is less hazardous and easier to handle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Transitioning to greener labs requires a revised inventory of go-to reagents. The following table details key solutions for replacing hazardous solvents and reagents.

Table 2: Essential Green Reagents and Solvents for the Modern Laboratory

| Item | Function & Green Chemistry Principle | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 2-MeTHF | Safer ether solvent for Grignard reactions, extractions, and as a polar aprotic solvent. (Principle #5: Safer Solvents) [25]. | Higher boiling point than THF; not a peroxide former; derived from renewable resources [25]. |

| Cyrene | Bio-based dipolar aprotic solvent for substitutions, polymer chemistry, and nanomaterials synthesis. Replaces DMF, NMP, and DMAc. (Principle #5: Safer Solvents; #7: Renewable Feedstocks) [25]. | Excellent toxicity profile; high boiling point; requires method re-optimization when substituting for DMF/DMAC. |

| Heptane | Aliphatic hydrocarbon solvent for chromatography, extractions, and as a reaction medium. Replaces hexane. (Principle #3: Less Hazardous Syntheses) [25]. | Much lower toxicity profile compared to the neurotoxin hexane; similar physical properties [25]. |

| Ethyl Acetate / Ethanol Blends | Green mobile phase for normal-phase and reverse-phase chromatography. Replaces DCM-containing systems. (Principle #5: Safer Solvents) [25]. | Effective eluting strength can be fine-tuned with ethanol; significantly safer than DCM [25]. |

| Water & Surfactant Solutions | Reaction medium for hydrolyses, oxidations, and as a solvent for extractions. Replaces organic solvents where possible. (Principle #5: Safer Solvents) [28]. | Non-toxic, non-flammable; can be used with surfactants to create micellar systems for organic reactions. |

| Heterogeneous Catalysts (e.g., Pd/C, Zeolites) | Catalytic reagents for hydrogenations, coupling reactions, and rearrangements. Replace stoichiometric reagents. (Principle #9: Catalysis) [24]. | Minimizes waste; often recyclable; separates easily from the reaction mixture. |

| Plant Extract Reductants | Utilizing natural extracts (e.g., from plants, algae) for the biosynthesis of nanomaterials. Replaces harsh chemical reducing agents. (Principle #6: Renewable Feedstocks; #3: Less Hazardous Syntheses) [29]. | Employs biorenewable molecules like polyphenols; avoids toxic sodium borohydride or hydrazine [29]. |

Visualization: A Strategic Framework for Solvent Substitution

The following diagram outlines a logical, step-by-step workflow for evaluating and replacing a hazardous solvent in a chemical process, aligning with the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry.

Figure 1: A decision workflow for replacing hazardous solvents in chemical processes.

Challenges and Limitations of Green Chemistry Transitions

While the advantages of green chemistry are compelling, several practical and conceptual limitations can impede its widespread adoption. Acknowledging these challenges is crucial for a realistic assessment and for guiding future research.

- Economic Feasibility: Developing new synthetic routes using greener solvents or designing safer chemicals often requires significant research and development investment. Companies, especially smaller ones, may be hesitant if they perceive greener methods as more expensive than traditional ones [26].

- Performance Trade-offs: In some cases, greener alternatives might not perform as well as their traditional counterparts. A bio-based plastic might have inferior mechanical properties, or a safer solvent might be less efficient, leading to lower yields or longer reaction times [26].

- Scalability: A green chemistry process that works effectively in a laboratory might not be easily scalable to industrial production. Factors such as raw material availability, energy requirements, and waste management become more critical and can introduce new challenges [26].

- Systemic and Infrastructural Inertia: The chemical industry is heavily invested in plants and equipment designed for traditional processes. Retrofitting these facilities for new green chemistry approaches can be prohibitively expensive, favoring incremental improvements over radical innovation [26].

- Risk of Greenwashing: There is a risk that industrial adoption focuses on superficial modifications rather than fundamental transformations. Switching to a slightly less toxic solvent while maintaining an unsustainable, high-volume linear production model does not achieve the full potential of green chemistry [26].

The limitations of hazardous reagents and solvents are no longer a peripheral concern but a central challenge in advancing organic synthesis and drug development. The tradition of using substances like benzene, DCM, and DMF is fraught with unacceptable risks to human health and the environment. The framework of Green Chemistry, articulated through its 12 principles, provides a robust, scientifically-grounded pathway forward.

The transition is not without its challenges, including economic barriers, performance trade-offs, and the inertia of established infrastructure [26]. However, the growing toolkit of safer, bio-based solvents like 2-MeTHF and Cyrene, coupled with established substitution protocols and strategic frameworks for implementation, provides researchers and drug development professionals with a clear and actionable guide. The future of sustainable chemistry lies in embracing this paradigm shift—moving beyond tradition to design molecular transformations that are not only efficient and elegant but also inherently safe and sustainable. This requires a continued commitment to research in green solvent and reagent design, lifecycle assessments, and a holistic, systems-based approach that integrates green chemistry with circular economy principles.

Life Cycle Thinking (LCT) represents a paradigm shift in chemical research and development, moving beyond traditional efficiency metrics to encompass a holistic view of environmental impacts across a chemical's entire life cycle. Within organic synthesis research, this approach integrates the 12 principles of green chemistry with rigorous life cycle assessment (LCA) methodologies to minimize environmental footprints from initial molecule design through ultimate disposal [3] [24]. The pharmaceutical and fine chemicals industries face increasing pressure to evaluate and improve the sustainability of their processes, particularly as studies reveal that traditional mass-based metrics alone provide insufficient guidance for comprehensive environmental impact reduction [30] [31].

The integration of LCT into molecular design is crucial because up to 80% of a product's lifetime environmental impacts are determined during the R&D phase [32]. This technical guide provides researchers with the frameworks, metrics, and experimental protocols needed to implement LCT throughout the drug development pipeline, enabling sustainability optimization at the earliest and most influential stages of research.

Theoretical Foundation: Bridging Green Chemistry and Life Cycle Assessment

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry as a Molecular Design Framework

The 12 principles of green chemistry, established by Anastas and Warner, provide a strategic framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances [3] [24]. When viewed through a life cycle lens, these principles extend beyond the reaction flask to encompass all stages of a chemical's existence:

Prevention of Waste emphasizes designing syntheses to prevent waste generation rather than treating or cleaning up waste after it is formed, considering waste streams across the entire production chain [24].

Atom Economy focuses on maximizing the incorporation of all starting materials into the final product, reducing resource consumption and waste generation at the molecular level [3].

Designing Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses advocates for the use and generation of substances with little or no toxicity to humans and the environment throughout the chemical life cycle [24].

The remaining principles similarly guide researchers toward systems that minimize energy consumption, utilize renewable feedstocks, employ catalytic processes, and design chemicals to degrade after use—all critical considerations for comprehensive life cycle management [3].

Life Cycle Assessment: Methodological Framework

Life Cycle Assessment provides a standardized, quantitative methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product's life, from raw material extraction ("cradle") to disposal ("grave") [33]. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) outlines four interdependent phases in the LCA framework [33]:

- Goal and Scope Definition: Establishing the objectives, system boundaries, and functional unit

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI): Compiling and quantifying inputs and outputs throughout the life cycle

- Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): Evaluating potential environmental impacts

- Interpretation: Analyzing results and making informed decisions

For pharmaceutical applications, most assessments follow a "cradle-to-gate" approach, encompassing all processes from raw material acquisition through API synthesis but excluding use and disposal phases due to regulatory and patient-specific complexities [30].

Implementing Life Cycle Thinking in Research and Development

Integrated Workflow for Sustainable Synthesis Design

The successful implementation of LCT requires an iterative approach that bridges molecular design and sustainability assessment. The following workflow visualization illustrates this integrated process:

Addressing Data Challenges in Early-Stage Assessment

A significant challenge in applying LCA to novel synthetic methodologies is the limited availability of life cycle inventory data for specialized intermediates, reagents, and catalysts. Current LCA databases such as ecoinvent contain approximately 1,000 chemicals, representing only a fraction of the compounds used in pharmaceutical synthesis [30]. For context, one study of a multistep synthesis found that only 20% of chemicals were present in standard LCA databases [30].

To address these limitations, researchers have developed several complementary approaches: