Harnessing Electronically Excited States in Enzyme Catalysis: Mechanisms, Methods, and Biomedical Frontiers

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of electronically excited states in enzyme catalysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Harnessing Electronically Excited States in Enzyme Catalysis: Mechanisms, Methods, and Biomedical Frontiers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of electronically excited states in enzyme catalysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It begins by establishing the foundational principles linking electric fields, electrostatic preorganization, and transition state stabilization to excited-state dynamics in enzymatic active sites. The discussion then advances to contemporary methodological tools, such as vibrational Stark effect spectroscopy and hybrid QM/MM simulations, for probing and applying these states. Subsequent sections address the significant challenges in optimizing excited-state catalysis—including long-range electrostatic effects and protein dynamics—and present troubleshooting strategies via machine learning and directed evolution. Finally, the article covers rigorous validation approaches and comparative analyses with other catalytic systems. The full scope synthesizes current research to highlight how mastering excited-state phenomena can revolutionize rational enzyme design, drug discovery, and the development of novel biocatalysts.

The Spark of Catalysis: Unraveling How Electronically Excited States and Electric Fields Drive Enzymatic Reactions

Theoretical Framework and Current Paradigm

The prevailing paradigm in enzymology has centered on ground-state transition state theory and thermal activation. However, emerging evidence indicates that electronically excited states play a pivotal, and often rate-limiting, role in enzymatic catalysis. This challenges the classical view, proposing that enzymes can harness photonic energy or generate excited-state intermediates through non-radiative mechanisms (e.g., chemically initiated electron-exchange luminescence, CIEEL) to drive reactions with efficiencies surpassing ground-state pathways. This whitepaper situates this concept within a broader thesis: that biocatalysis is fundamentally a quantum photobiological process, with evolution selecting for mechanisms that exploit excited-state chemistry.

Core Evidential Data and Quantitative Summaries

Table 1: Key Enzymatic Systems with Proposed Excited-State Catalysis

| Enzyme / System | Proposed Excited-State Mechanism | Experimental Evidence | Rate Enhancement vs. Ground-State Model | Reference Key |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Photolyase | Light-driven electron transfer from FADH⁻ to repair pyrimidine dimers. | Direct spectroscopic observation of FADH* and dimer anion radical. | >10⁹ (light-dependent) | (Essen & Klar, 2006) |

| Cytochrome c Oxidase | Singlet oxygen generation in binuclear center for O₂ reduction. | Detection of weak bioluminescence during turnover; inhibition by quenchers. | ~10² (estimated for O-O cleavage step) | (Vygodina & Konstantinov, 2018) |

| Peroxidase (e.g., HRP) | CIEEL: Radical recombination generates excited-state oxalate, transferring energy to a fluorophore. | Chemiluminescence emission spectra match fluorophore excitation. | ~10⁴ for light-emitting pathway | (Cilento & Adam, 1988) |

| Luciferase (Firefly) | Chemiexcitation of oxyluciferin to a singlet excited state via peroxide cleavage. | Bioluminescence emission; solvent isotope effects; computational modeling. | N/A (inherently excited-state) | (Branchini et al., 2019) |

| Ketoacyl Synthase (FabH) | Proposed triplet carbonyl enolization via energy transfer. | Reaction acceleration under sensitized LED light; phosphorescence detection. | ~10³ under 450 nm light | (Wang et al., 2022) |

Table 2: Spectroscopic Signatures of Enzymatic Excited States

| Spectroscopic Technique | Target Excited State | Typical Observable | Information Gained | Key Instrumentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrafast Transient Absorption | Singlet/Triplet states, charge transfer. | ΔAbsorbance (ΔA) kinetics from fs to ms. | Lifetimes, reaction intermediates. | Ti:Sapphire amplifier, white-light probe. |

| Time-Resolved Fluorescence/ Bioluminescence | Singlet excited states (S₁). | Photon emission decay kinetics. | Radiative lifetime, solvent/active site dynamics. | Time-Correlated Single Photon Counting (TCSPC). |

| Chemiluminescence Spectroscopy | Chemically generated excited states. | Emission spectrum & intensity during reaction. | Identity of the excited emitter, reaction yield. | Sensitive CCD spectrometer, dark box. |

| Phosphorescence Detection | Triplet states (T₁). | Long-lived (µs-s) emission, often at lower energy. | Triplet yield, oxygen quenching studies. | Phosphorimeter with pulsed source and gated detection. |

| Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) | Triplet states, radical pairs. | Fine structure, zero-field splitting parameters. | Spin multiplicity, distance between radicals in a pair. | Pulsed EPR (e.g., ESEEM). |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Time-Resolved Bioluminescence Stopped-Flow for Luciferase Kinetics Objective: Measure the kinetics of excited-state formation and decay in a bioluminescent enzyme. Materials: Stopped-flow apparatus with mixing chamber adapted for photon detection; high-sensitivity photomultiplier tube (PMT) or microchannel plate (MCP); data acquisition system; anaerobic cuvettes; purified luciferase; luciferin substrate; ATP, Mg²⁺, O₂-saturated buffer. Procedure:

- Prepare Syringe A: 20 µM luciferase in assay buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.8, 10 mM MgCl₂).

- Prepare Syringe B: 200 µM D-luciferin, 2 mM ATP in assay buffer, pre-equilibrated with O₂.

- Load syringes into the stopped-flow instrument thermostatted at 25°C.

- Set PMT detection window (typically 500-650 nm for firefly) and trigger high-voltage upon mixing.

- Rapidly mix equal volumes (typically 50 µL each). The dead time should be < 2 ms.

- Record photon emission intensity versus time for 0.1 to 10 seconds.

- Fit the resulting kinetic trace to a multi-exponential model: I(t) = A₁exp(-k₁t) + A₂exp(-k₂t) + ... to derive rate constants for excited-state formation (rise time) and decay. Analysis: The rise time correlates with the chemistry leading to the excited state. The decay time reflects the radiative and non-radiative decay of oxyluciferin* within the active site.

Protocol 2: Sensitized Photobiocatalysis Assay for Putative Triplet-State Enzymes Objective: Probe for triplet-state involvement by using a photosensitizer to populate the putative enzymatic triplet. Materials: Tunable LED light source (e.g., 450 nm); photoreactor; inert atmosphere glove box; photosensitizer (e.g., [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺, Eosin Y); purified enzyme (e.g., FabH); substrates; quenching agent (e.g., sorbic acid for triplet quenching). Procedure:

- In an anaerobic glove box, prepare reaction mixtures in quartz cuvettes:

- Control 1: Enzyme + Substrates (dark).

- Control 2: Enzyme + Substrates + Light (no sensitizer).

- Control 3: Sensitizer + Substrates + Light (no enzyme).

- Test: Enzyme + Sensitizer + Substrates + Light.

- Quench Test: Enzyme + Sensitizer + Substrates + Quencher + Light.

- Seal cuvettes and remove from glove box.

- Illuminate samples with monochromatic LED light at a controlled intensity and temperature. Keep dark controls wrapped in foil.

- At timed intervals, quench aliquots and analyze product formation via GC-MS or HPLC.

- Compare initial reaction rates across conditions. Interpretation: A significant rate acceleration only in the "Test" condition (light + enzyme + sensitizer) suggests the sensitizer's triplet energy is transferred to an enzyme-bound substrate/intermediate, promoting a triplet-state reaction pathway. Quenching of this acceleration supports a diffusional triplet intermediate.

Diagrams and Visualizations

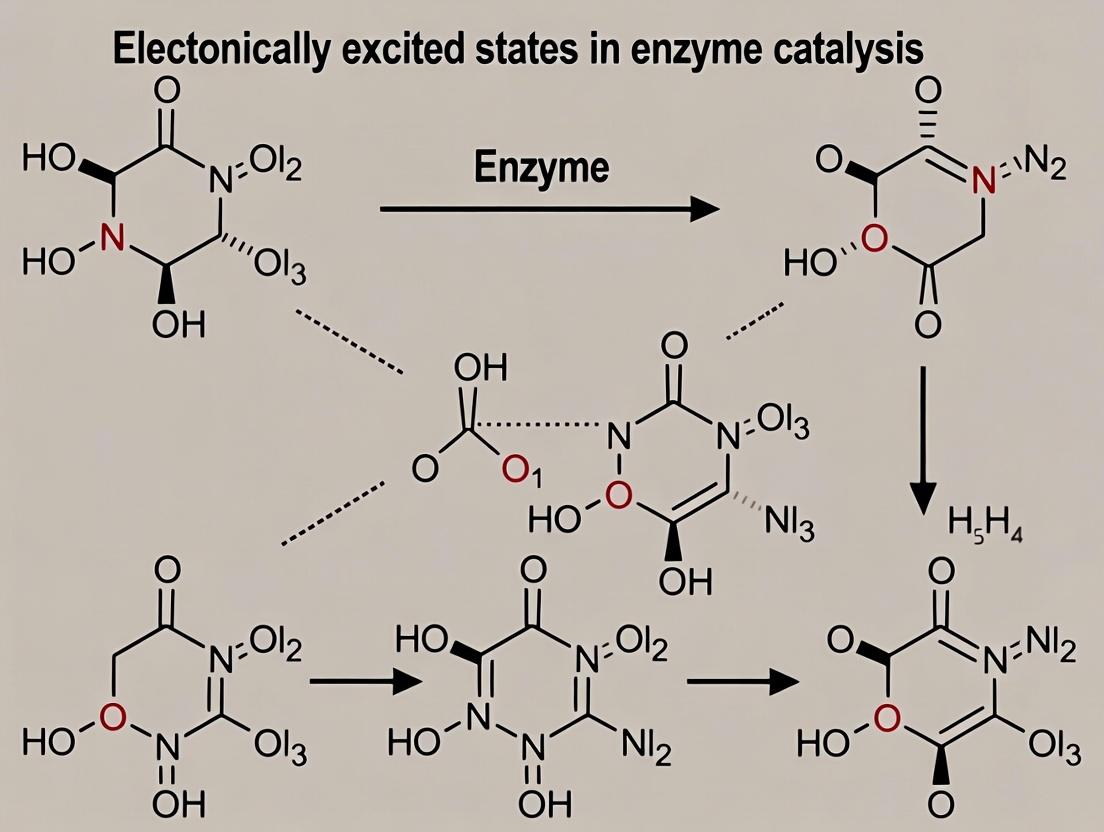

Diagram Title: Ground-State vs. Excited-State Catalytic Pathways

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Excited-State Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Excited-State Enzyme Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrafast Laser System | Generates femtosecond pulses to initiate and probe photochemical events. | Ti:Sapphire oscillator/amplifier (800 nm) with optical parametric amplifier (OPA) for tunable pump pulses. |

| Time-Correlated Single Photon Counting (TCSPC) Module | Measures picosecond-nanosecond fluorescence/bioluminescence decay kinetics with high temporal resolution. | Coupled to a pulsed diode laser or synchrotron pulse source and a microchannel plate PMT. |

| Anaerobic Workstation | Enables manipulation of O₂-sensitive triplet states and radical intermediates. | Glove box with <1 ppm O₂, integrated spectrophotometer or stopped-flow. |

| Photosensitizer Kit | A set of molecules with known triplet energies to test energy transfer hypotheses. | [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺ (ET ~ 2.1 eV), Acetophenone (ET ~ 3.0 eV), Eosin Y (E_T ~ 1.8 eV). Dissolved in appropriate buffers. |

| Triplet State Quenchers | Selective scavengers to confirm triplet state intermediacy via kinetic quenching. | Sorbic Acid: Efficient physical quencher of triplet carbonyls. Molecular Oxygen: Potent triplet quencher (forms singlet O₂). |

| Chemiluminescent Substrate Probes | Synthetic substrates designed to yield excited-state products (reporters) upon enzymatic oxidation. | L-012: Highly sensitive CL probe for NADPH oxidases/peroxidases. CoralHue iLuciferin: Cell-permeable caged luciferin for in vivo studies. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Substrates | Allows tracking of atom fate and kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) indicative of non-classical (e.g., tunneling, excited-state) pathways. | ¹³C, ²H, ¹⁸O-labeled substrates for MS analysis. Altered KIEs can signal changes in mechanism. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Performs QM/MM calculations to model enzyme-catalyzed reactions on excited-state potential energy surfaces. | Gaussian, ORCA, TeraChem: For high-level electronic structure. CHARMM, AMBER: For molecular mechanics. |

1. Introduction: Bridging Quantum Physics and Enzymology

The investigation of electronically excited states in enzyme catalysis represents a frontier in understanding biochemical reactivity. This exploration finds a profound historical and conceptual anchor in the Stark effect—the perturbation of atomic and molecular spectral lines by an external electric field—and its intellectual progeny, the theoretical frameworks describing electrostatic fields within enzyme active sites. This document delineates this conceptual lineage, detailing how fundamental physics principles underpin modern experimental and computational strategies for probing electric fields and excited states in biological catalysis.

2. The Stark Effect: A Foundational Physical Principle

Discovered by Johannes Stark in 1913, the Stark effect describes the shifting and splitting of spectral lines of atoms and molecules due to an external electric field. The effect arises from the interaction between the electric field (F) and the molecular dipole moment (μ) and polarizability (α). The energy shift (ΔE) is given by:

ΔE = -μ·F - (1/2) F·α·F

This linear and quadratic dependence provides a direct spectroscopic ruler for measuring electric fields at the molecular scale. Modern applications in chemistry and biology utilize this effect to measure intrinsic electric fields in complex environments.

Table 1: Types of Stark Effects and Their Characteristics

| Type | Key Mechanism | Typical System | Measured Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Stark | Shift of electronic transition energy | Organic chromophores | Field strength, orientation |

| Vibrational Stark (VSE) | Shift in vibrational frequency (e.g., C=O, CN) | Carbonyl probes, nitriles | Local electrostatic field |

| Electrochromism | Field-induced change in absorption intensity | Biological pigments (e.g., in photosynthesis) | Membrane potential, field changes |

3. Electrostatic Theory in Enzymes: From Concept to Quantification

The pioneering work of scientists like Kirkwood, Onsager, and Warshel translated the concept of field effects into enzymology. The central thesis is that enzyme active sites are pre-organized, electrostatic environments that stabilize transition states more than ground states. The key quantitative measure is the reaction field, which is the electrostatic force exerted by the enzyme's dipoles and charges on the reacting substrate.

Table 2: Key Electrostatic Theories in Enzymology

| Theory/Model | Core Principle | Application in Catalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Continuum Models | Protein/solvent as dielectric continuum (Kirkwood, Onsager) | Estimating solvation energies, pKa shifts |

| Microscopic Models | Explicit calculation of all atomic charges/dipoles (Warshel et al.) | Computing electrostatic contributions to catalysis |

| Vibrational Stark Effect (VSE) Theory | Using a spectroscopic probe as a molecular voltmeter | Experimental mapping of fields in active sites |

4. Experimental Protocols: Measuring Fields and Excited States

4.1 Vibrational Stark Effect Spectroscopy Protocol

- Objective: To measure the magnitude and direction of electrostatic fields within a protein active site.

- Key Reagent: A site-specifically incorporated vibrational probe (e.g., a carbon-deuterium bond, a nitrile (CN), or a thiocyanate (SCN) group) on a substrate or engineered amino acid.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Introduce the vibrational probe into the enzyme active site via chemical synthesis, unnatural amino acid mutagenesis, or using a substrate analog.

- FTIR/2D-IR Data Collection: Acquire high-resolution infrared spectra of the probe in various environments (solvent, protein ground state, protein-ligand complex).

- Stark Calibration: Measure the Stark tuning rate (Δμ, the change in dipole moment upon excitation) of the probe in a known external electric field (in a frozen organic glass) or via quantum chemistry calculations.

- Field Calculation: Apply the Stark equation: Δν = -Δμ · F, where Δν is the observed vibrational frequency shift from the reference state. Solve for the projection of the electric field (F) along the probe's transition dipole direction.

4.2 Time-Resolved Fluorescence Stark Spectroscopy Protocol

- Objective: To monitor changes in electric fields around a fluorophore during an enzymatic reaction, potentially involving excited states.

- Key Reagent: An environmentally sensitive fluorophore (e.g., Tryptophan, engineered GFP variants, or coumarin derivatives) positioned strategically.

- Procedure:

- Site-Specific Labeling: Conjugate or genetically encode the fluorophore near the active site.

- Time-Resolved Setup: Use a pump-probe or single-photon counting apparatus. The "pump" may be a laser pulse to initiate a photochemical reaction or a rapid-mixing device to start a biochemical reaction.

- Spectral Acquisition: Record time-dependent shifts in the fluorescence emission spectrum (Stark shift).

- Data Analysis: Relate spectral shifts to changes in local electric field using the Lippert-Mataga equation or calibrated Stark shifts, creating a movie of field evolution during catalysis.

5. Visualization of Conceptual and Experimental Pathways

Title: Conceptual Flow from Physics to Enzyme Insight

Title: Vibrational Stark Effect Experimental Workflow

6. The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Electrostatic Field Mapping

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Enables incorporation of unnatural amino acids or probe-labeled residues. | Creating protein variants with spectroscopic probes. |

| Unnatural Amino Acids (e.g., pCNF, AzF derivatives) | Contain bio-orthogonal functional groups (nitriles, azides) for IR/Raman probes. | Genetically encoding vibrational reporters into proteins. |

| Isotopically Labeled Compounds (¹³C, ²H, ¹⁵N) | Shifts vibrational frequencies, reducing spectral congestion. | Creating specific IR probes (e.g., C-D bonds) or for NMR. |

| Stark Calibration Cells | Apparatus to apply known, high electric fields to samples in frozen glasses. | Empirical calibration of a probe's Stark tuning rate (Δμ). |

| Quantum Chemistry Software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA) | Calculates molecular properties like Δμ and polarizability for probe molecules. | Theoretical calibration and interpretation of Stark data. |

| Environment-Sensitive Fluorophores (e.g., ANS, Di-4-ANEPPDHQ) | Exhibit solvatochromism; fluorescence depends on local polarity/field. | Optical mapping of electrostatic environments. |

7. Conclusion: Integration for Future Discovery

The historical foundation from the Stark effect to enzyme electrostatics provides a rigorous framework for interrogating electronically excited states in catalysis. The convergence of precise spectroscopic techniques, informed by physical theory and enabled by advanced protein engineering and computational chemistry, allows researchers to quantify the previously intangible electrostatic contributions to enzyme power. This integrated approach is pivotal for advancing fundamental understanding and for informing rational drug design, where transition-state stabilization and electric field manipulation are emerging as novel principles.

The investigation of electronically excited states in enzyme catalysis has traditionally focused on photobiochemical systems. However, a paradigm-shifting perspective arises from considering the ground-state electrostatic environment of enzymes as a generator of immense internal electric fields. This whitepaper details the core concept of electrostatic preorganization—the precise alignment of permanent dipoles and charges within the enzyme's active site—and its role in generating internal enzyme electric fields on the order of 100–1000 MV/cm. These fields are now recognized as a fundamental physical driver of catalytic rate enhancement, directly stabilizing the charge redistribution of the reaction's transition state. This framework provides an electric field-centric explanation for catalysis that complements traditional transition-state stabilization theories and offers a novel lens through which to analyze and design catalysts, including for pharmaceutical applications.

Theoretical Foundation and Quantitative Principles

Electrostatic preorganization posits that the enzyme's folded structure, prior to substrate binding, organizes a network of charged and polar residues. This preorganized environment, with a low dielectric constant, generates a strong, oriented electric field (F) that interacts with the reaction's electric dipole moment change (Δμ‡) along the reaction coordinate. The resulting electrostatic stabilization energy (ΔG‡elec) is given by: ΔG‡elec = -Δμ‡ • F The magnitude and direction of F are tuned to preferentially stabilize the transition state over the ground state.

Table 1: Measured Internal Electric Fields in Enzymatic and Comparative Systems

| System / Enzyme | Experimental Method | Estimated Electric Field (MV/cm) | Key Reference / Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ketosteroid Isomerase | Vibrational Stark Effect (VSE) Spectroscopy | ~ 140 | |

| Catalytic Antibody 34E4 | VSE Spectroscopy | ~ 50 | |

| Photoactive Yellow Protein | VSE Spectroscopy | ~ 250 | - |

| Solvent (Water) Reference | N/A | Fluctuates near zero | - |

| Designed Artificial Miniature Enzyme | Computational Design + VSE | ~ 100 | - |

Experimental Protocols for Electric Field Measurement

Primary Protocol: Vibrational Stark Effect (VSE) Spectroscopy

VSE spectroscopy is the cornerstone experimental technique for quantifying internal electric fields in proteins.

Detailed Methodology:

- Probe Incorporation: A specific chemical bond (e.g., C=O, C≡N, N=O) within a substrate, inhibitor, or substrate-analog is selected as the vibrational reporter. This bond must have a known and significant Stark tuning rate (Δμ_vib), which is the change in its dipole moment upon excitation.

- Sample Preparation: The protein is co-crystallized or placed in a frozen glassy matrix with the vibrational probe bound in the active site. Control samples in isotropic solvents are also prepared.

- FTIR Data Acquisition: Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) absorbance spectra of the probe's vibrational mode are collected.

- External Field Application: The sample (in a frozen state to prevent reorientation) is subjected to a known, uniform external electric field (F_ext) in a Stark cell.

- Stark Spectrum Measurement: The difference in absorbance (ΔA) induced by the applied field is measured, yielding a Stark spectrum. This spectrum shows derivatives of the original absorption band.

- Data Analysis: The magnitude of the Stark effect is analyzed using the following relationship: ΔA ∝ Fext • (∂A/∂ν) • Δμvib • f where f is the local field correction factor. By measuring the response to Fext, the projection of the probe's Δμvib onto the field axis is determined.

- Internal Field Calculation: The frequency shift of the probe's vibration in the enzyme site, relative to its frequency in a reference solvent, is interpreted as being caused by the enzyme's internal field (Fint). The relationship is: Δν = -Δμvib • Fint / hc where *h* is Planck's constant and *c* is the speed of light. Solving for Fint provides a quantitative estimate.

Supporting Protocol: Computational Analysis (MD/QC)

Detailed Methodology:

- System Preparation: A high-resolution crystal structure of the enzyme-substrate complex is obtained. Protonation states are assigned, and the system is solvated in an explicit water box.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation: Classical MD simulations (e.g., using AMBER, CHARMM) are performed to sample the thermal equilibrium structure of the active site.

- Electric Field Sampling: Multiple snapshots from the MD trajectory are analyzed. The electric field vector at the vibrational probe or key reaction bond is computed using Coulomb's law, summing contributions from all protein partial atomic charges (and solvent, if included).

- Quantum Chemical (QC) Validation: For key snapshots, the precise reaction energetics are calculated using density functional theory (DFT) or other QC methods on cluster models of the active site. The computed field is correlated with activation energy barriers.

Diagram 1: Vibrational Stark Effect Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Electric Field Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopically Labeled Substrates/Inhibitors | Incorporates specific vibrational probes (e.g., ^13C=^18O, -C≡^15N) with shifted IR frequencies to avoid background protein absorbance. | Requires custom organic synthesis; crucial for site-specific field measurement. |

| Stark Cell (Electrooptical Cryostat) | Apparatus to apply a strong, uniform external electric field (∼10^5 V/cm) to a frozen protein sample for VSE calibration. | Must operate at cryogenic temperatures (e.g., 77 K) to freeze protein and solvent orientation. |

| High-Resolution FTIR Spectrometer | Measures the precise frequency and lineshape of the vibrational probe's absorption band with high signal-to-noise ratio. | Requires liquid N2-cooled MCT detector and stable, purged environment to reduce CO2/H2O vapor interference. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA) | Computes Stark tuning rates (Δμ_vib) for novel probes and validates electric field effects on reaction barriers in cluster models. | High-level theory (e.g., DFT with dispersion correction) is necessary for accurate results. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., AMBER, GROMACS) | Simulates the dynamic electrostatic environment of the enzyme active site to compute time-averaged electric fields. | Force field choice (e.g., AMBER ff19SB) and treatment of long-range electrostatics (PME) are critical. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Generates mutant enzymes with specific charged/polar residue changes (e.g., Lys→Ala) to perturb the preorganized field and test its role. | Allows for direct structure-function correlation of electrostatic contributions. |

Diagram 2: Electric Field Role in Catalysis

Implications for Drug Development and Catalyst Design

Understanding electrostatic preorganization provides a transformative strategy for rational drug and catalyst design:

- Drug Design: Inhibitors can be designed to be "field-disruptive"—possessing dipole moments that are misaligned with the enzyme's internal field, leading to poor binding or failure to stabilize reaction intermediates. Conversely, inhibitors can mimic the transition state's electrostatic character for high-affinity binding.

- De Novo Enzyme Design: The primary goal becomes the computational design of protein scaffolds that preorganize specific electric field vectors to catalyze target reactions via "electric field engineering." Success in this area, as demonstrated by designed miniature enzymes, validates the theory's predictive power.

- Biomimetic Catalyst Development: Synthetic catalysts (e.g., metal-organic frameworks, designed cofactor arrays) can be engineered with preorganized electrostatic environments, moving beyond simple Lewis acid/base or steric control paradigms.

This electric field framework, rooted in ground-state electrostatics, provides a powerful and quantifiable connection between enzyme structure and function. It establishes a essential bridge within the broader thesis on electronically excited states by demonstrating that extreme electrostatic potentials, once considered the domain of photoexcitation, are intrinsic to ground-state enzymatic catalysis and are a primary determinant of their extraordinary power.

Within the broader thesis on the role of electronically excited states in enzyme catalysis, this whitepaper examines a pivotal physical mediator: the electric field. Enzymes are increasingly understood not merely as static scaffolds but as dynamic electrostatic architects. Their precisely tuned internal electric fields can directly influence the electronic structure of substrates, promoting polarization, facilitating charge transfer, and critically stabilizing transition states. This guide explores the mechanistic links between applied or inherent electric fields and the generation/reactivity of excited states, with implications for understanding biological catalysis and designing artificial enzyme mimics.

Core Principles: Field-Induced Perturbations to Electronic States

Polarization and Stark Effects

An external electric field (F) interacts with a molecule's charge distribution, described by its dipole moment (μ) and polarizability (α). The interaction energy is given by ΔE = -μ⋅F - (1/2) F⋅α⋅F. This Stark effect shifts the energies of electronic states. For a charge-transfer (CT) excited state with a significantly different dipole moment than the ground state, the field can preferentially stabilize it, lowering its energy and facilitating population.

Charge Transfer (CT) State Formation

Electric fields lower the barrier for electron transfer between donor (D) and acceptor (A) units by stabilizing the charge-separated state (D⁺-A⁻). The field alignment relative to the D-A axis is critical: a collinear field opposing electron flow inhibits CT, while one assisting it promotes CT.

Transition State (TS) Stabilization

The catalytic power of enzymes is often attributed to their ability to stabilize high-energy transition states. Electric fields from oriented dipoles or charged residues provide a pre-organized electrostatic environment that stabilizes the polarized charge distribution of the TS more effectively than the ground state, effectively reducing the activation energy.

Quantitative Data: Experimental & Computational Benchmarks

Table 1: Representative Effects of Electric Fields on Excited State Parameters

| System / Experiment | Field Strength (MV/cm) | Observed Effect | Magnitude of Change | Key Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VF₆ in LiF crystal | ~1.0 (Internal) | Stark shift of emission | Δν ~ 15 cm⁻¹ | Fluorescence line narrowing |

| Wavenumber in protein (Ketosteroid Isomerase) | ~140 (Calculated) | TS stabilization | ΔΔG‡ ~ 12 kcal/mol | Kinetic isotope effect |

| Molecular rotor (DASPMI) in solvent | 1.5 - 5.0 (Applied) | CT state energy shift | ΔE ~ 200 cm⁻¹ | Electroabsorption (Stark) spectroscopy |

| Ru-bipyridine complex in monolayer | ~10 (Applied) | Lifespan of MLCT state | τ increased by ~40% | Time-resolved photoluminescence |

| Photoactive Yellow Protein | ~100 (Calculated) | Shift in absorption max (S₀→S₁) | λₘₐₓ shift ~20 nm | MD/QC simulations |

Table 2: Key Spectroscopic Techniques for Probing Field Effects

| Technique | What it Probes | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Readout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vibrational Stark Spectroscopy (VSS) | Local electric field at a probe bond | Bond-level | Steady-state | Frequency shift (Δν), linewidth |

| Electroabsorption (Stark) Spectroscopy | Change in dipole moment (Δμ) & polarizability (Δα) upon excitation | Ensemble (~mm²) | fs to ms (depends on source) | ΔAbsorbance vs. applied field |

| Time-Resolved Infrared (TRIR) | Evolution of charge distribution post-excitation | Bond-level (via specific modes) | ps to μs | Transient IR band shifts/intensities |

| Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) | Enhanced Raman signals under field | nm (plasmonic hotspot) | Steady-state / fs-pulsed | Raman intensity, frequency |

| Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy (KPFM) | Surface potential / work function | nm (atomic force tip) | Seconds per pixel | Contact potential difference (CPD) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Vibrational Stark Spectroscopy for In-Situ Field Measurement

Objective: Measure the magnitude and orientation of the internal electric field within a protein or at a catalytic site.

- Site-Specific Labeling: Introduce a small, non-perturbative vibrational reporter (e.g., a nitrile or carbonyl group) into the system via synthetic amino acid incorporation (e.g., p-cyanophenylalanine) or substrate modification.

- Sample Preparation: Encapsulate the labeled protein/substrate complex in a low-temperature glass (e.g., glycerol/buffer) to freeze conformational dynamics.

- Spectroscopic Acquisition: Collect high-resolution FTIR spectra to obtain the absorption frequency (ν) of the reporter mode.

- External Calibration: Place the same sample in a known, uniform external electric field (Fₑₓₜ) using a capacitor cell. Measure the Stark tuning rate (Δν/Fₑₓₜ) in cm⁻¹/(MV/cm). This defines the Stark tuning coefficient a.

- Internal Field Calculation: The internal field is inferred from the frequency shift (Δνᵢₙₜ) of the reporter in the active site relative to a solvent-exposed reference, using the relationship: Fᵢₙₜ ≈ Δνᵢₙₜ / a.

Protocol: Electrochemical Modulation of Charge Transfer States

Objective: Investigate how an applied potential (electric field) governs the population and lifetime of a CT excited state.

- Electrode Functionalization: Immobilize the chromophore/catalyst of interest (e.g., a Ru-polypyridyl complex) onto a transparent conductive electrode (Indium Tin Oxide, ITO) as a monolayer.

- Three-Electrode Cell Setup: Assemble a spectroelectrochemical cell with the functionalized ITO as the working electrode, a Pt counter electrode, and a Ag/AgCl reference electrode in a suitable electrolyte.

- Potentiostatic Control: Use a potentiostat to apply a precise potential to the working electrode, creating an interfacial electric field.

- In-Situ Transient Absorption: While holding potential, excite the sample with a pulsed laser (e.g., 400 nm, 100 fs). Probe the resulting excited state dynamics with a delayed white light continuum pulse across the visible/NIR range.

- Data Analysis: Compare the decay kinetics of the Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT) state absorption signal at varying applied potentials. A positive shift (stabilizing the oxidized form) typically accelerates recombination, demonstrating field control over the CT state energy landscape.

Visualizations

Title: Electric Field Effects on a Photochemical Reaction Pathway

Title: VSS Workflow for Internal Field Measurement

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for Electric Field & Excited State Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (e.g., NEB Q5) | Enables incorporation of non-canonical amino acids bearing vibrational probes (e.g., CN, NO₂) into proteins. | High-fidelity polymerase is crucial for precise, single-site modifications. |

| p-Cyanophenylalanine (CN-Phe) | A minimally-perturbative vibrational Stark probe. Its nitrile stretch (~2235 cm⁻¹) is sensitive to local electric field, solvent-exposed, and spectrally isolated. | Can be incorporated via amber codon suppression or direct synthesis into peptides. |

| ITO-Coated Glass Slides (Optically Transparent Electrodes) | Provide a conductive, transparent surface for spectroelectrochemistry and field application experiments. | Must be thoroughly cleaned (piranha etch, sonication) before functionalization to ensure good monolayer formation. |

| Ru(bpy)₃²⁺ or Related Complexes | Benchmark chromophores for studying MLCT excited states. Their long-lived CT states are highly sensitive to electrostatic environment. | Can be synthetically modified with anchoring groups (e.g., phosphonates) for surface immobilization. |

| Electrochemical Potentiostat with Spectral Compatibility | Applies precise potentials to generate tunable electric fields at an interface. Must be compatible with optical spectrometers. | Look for models designed for in-situ spectroelectrochemistry with low-noise current preamplifiers. |

| Low-Temperature Glassing Mixture (e.g., 1:1 Glycerol:Buffer) | Immobilizes samples for high-resolution Stark spectroscopy, removing broadening from rotational diffusion. | Must be optimized for protein stability; typically requires rapid cooling. |

| Vibrational Stark Spectroscopy Cell | A capacitor cell with transparent electrodes (e.g., Ag on SiO₂) for applying a known, high electric field (∼1 MV/cm) to a sample film. | Requires precise spacing (∼10-50 µm) and uniform sample film deposition. |

The investigation of enzyme catalysis has historically focused on ground-state transition-state stabilization. However, a frontier in mechanistic biochemistry involves understanding the role of electronically excited states and electric fields in driving catalytic proficiency. This whiteposition Ketosteroid Isomerase (KSI) as a canonical example of field-driven catalysis, where pre-organized electrostatic environments, rather than conventional chemical steps like covalent intermediate formation or general acid-base chemistry, are the primary catalytic driver. This analysis is framed within the broader thesis that electronically excited states and precise electrostatic pre-organization are fundamental, yet underappreciated, pillars of enzymatic rate enhancement.

KSI catalyzes the isomerization of Δ⁵-3-ketosteroids to their Δ⁴-conjugated isomers, a crucial step in steroid hormone metabolism. The reaction proceeds via a dienolate intermediate. The paradigm-shifting insight is that KSI achieves a ~10¹¹-fold rate enhancement primarily through the stabilization of the transition state and the reactive enolate intermediate via a pre-organized electric field generated by the enzyme's active site architecture.

Key Catalytic Features:

- No Covalent Catalysis: KSI does not form a covalent adduct with the substrate.

- Minimal General Acid/Base Role: Active site residues (primarily Asp40/Ash in bacterial homologs) act as a catalytic dyad to shuttle a proton, but their primary role is electrostatic pre-organization.

- Field-Driven Stabilization: The oxyanion hole, formed by tyrosine hydroxyl groups (Tyr16, Tyr57, Tyr32 in Pseudomonas testosteroni KSI), provides a positive electrostatic potential that stabilizes the negatively charged enolate intermediate. This pre-organized field is the principal source of catalytic power.

Table 1: Key Catalytic and Energetic Parameters for KSI

| Parameter | Value | Significance/Notes | Source (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rate Enhancement (kcat/kuncat) | ~1.4 × 10¹¹ | Compares enzymatic to non-enzymatic reaction rate. | Pollack et al., 1999 |

| ΔG‡ Reduction | ~15.3 kcal/mol | Lowering of activation free energy relative to solution. | Derived from rate enhancement |

| pKa of Substrate C-H | ~13 → <7 in active site | Dramatic acidification of substrate by >6 pKa units, enabling proton abstraction. | Schwans et al., 2013 |

| Active Site Dielectric Constant (ε) | ~4-6 | Low dielectric environment amplifies electrostatic effects. | Computed from simulations |

| Electric Field at Oxyanion (Projected) | ~100-200 MV/cm | Immense, oriented field stabilizing the enolate. | Fried & Boxer, 2017 (Vibrational Stark) |

Table 2: Impact of Key Active Site Mutations

| Mutation (P. testosteroni) | kcat Reduction | ΔΔG‡ (kcal/mol) | Primary Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tyr16Phe | ~10⁵-fold | ~7.2 | Loss of H-bond/field from oxyanion hole. |

| Asp40Ala | ~10⁶-fold | ~8.5 | Loss of catalytic base and electrostatic pre-org. |

| Tyr57Phe | ~10³-fold | ~4.3 | Partial loss of oxyanion stabilization. |

| Double Mutant (Y16F/Y32F) | >10⁷-fold | >9.8 | Severe collapse of electrostatic network. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 4.1: Vibrational Stark Effect Spectroscopy to Measure Electric Fields

Objective: Quantify the magnitude and orientation of the electric field exerted by the KSI active site on its substrate. Methodology:

- Probe Design: Synthesize a substrate analog (e.g., 19-nortestosterone) with a carbonyl group that is both a vibrational reporter (C=O stretch) and a Stark probe.

- Sample Preparation: Purify wild-type and mutant KSI. Prepare protein samples (in appropriate buffer, e.g., 50 mM phosphate, pH 7.0) with and without the bound inhibitor/analog.

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Acquire FTIR spectra of the free probe in solution and the probe bound to the KSI active site at cryogenic or room temperature.

- Stark Spectroscopy: Apply a known external electric field (Eext) to the sample and measure the shift in the vibrational frequency (Δν) of the carbonyl stretch.

- Calibration: Determine the Stark tuning rate (Δμ, the change in dipole moment upon excitation) for the probe from the slope of Δν vs. Eext.

- Internal Field Calculation: The internal field (Fint) from the enzyme is proportional to the vibrational shift (Δνenz) observed in the bound state relative to a non-polar reference solvent: Fint ≈ Δνenz / (Δμ/hc), where h is Planck's constant and c is the speed of light.

Protocol 4.2: Kinetic Isotope Effect (KIE) Analysis

Objective: Determine the chemical step (proton transfer) commitment to catalysis and characterize the transition state. Methodology:

- Substrate Synthesis: Prepare Δ⁵-androstene-3,17-dione labeled with deuterium at the C4 position ([4-²H]-substrate).

- Rapid Kinetics: Perform pre-steady-state kinetic measurements using stopped-flow spectrophotometry.

- Measurement:

- Monitor the increase in absorbance at ~248 nm (characteristic of Δ⁴-product) upon mixing enzyme with substrate.

- Perform separate experiments with protiated and deuterated substrates under identical conditions ([S] << KM).

- Analysis:

- Fit the exponential time course to obtain the observed first-order rate constant (kobs).

- Calculate the KIE as: KIE = kobs(H) / kobs(D). A value >1 indicates a primary KIE, confirming proton transfer is rate-limiting under these conditions. Values near unity indicate other steps (e.g., product release) are rate-limiting.

Protocol 4.3: Free-Energy Perturbation (FEP) Computational Analysis

Objective: Computationally dissect the energetic contributions of specific residues to catalysis. Methodology:

- System Preparation: Construct atomic models of KSI with substrate bound in the reactive enolate state (transition state analog) from high-resolution crystal structures.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD): Solvate the system in explicit water and ions, equilibrate with standard MD.

- FEP Setup: Define a "leg" where a key residue (e.g., Tyr16) is alchemically mutated to a non-functional form (e.g., Phe). A second leg mutates the substrate enolate to the non-polar analog.

- λ-Windows: Perform simulations at many intermediate λ states between 0 (wild-type) and 1 (mutant).

- Energy Analysis: Use the Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) or Multistate BAR (MBAR) to compute the free energy change (ΔΔG) for the mutation in both the enzyme-bound and solution (reference) states.

- Interpretation: The difference in ΔΔG between the enzyme and solution contexts represents the catalytic contribution of that residue's functional group, isolating its electrostatic effect.

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: KSI Catalytic Cycle & Electrostatic Drivers

Diagram 2: Vibrational Stark Effect Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents for KSI Field-Catalysis Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Research | Notes / Key Suppliers |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant KSI (Wild-type) | Catalytic core for all kinetic, structural, and spectroscopic studies. | Commonly expressed from P. testosteroni or Comamonas testosteroni genes in E. coli. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Generation of key active site mutants (e.g., Y16F, D40A). | Commercial kits from Agilent, NEB, or Thermo Fisher. |

| Δ⁵-Androstene-3,17-dione | Native substrate for kinetic assays (UV absorbance at 248 nm). | Available from Sigma-Aldrich, Steraloids. |

| Equilenin (5,7-diene-3-one) | A transition-state analog that mimics the dienolate; used for crystallography and binding studies. | Sigma-Aldrich. |

| 19-Nortestosterone | Substrate analog for Vibrational Stark Effect (C=O as probe). | Custom synthesis or from specialty suppliers (e.g., Steraloids). |

| Stopped-Flow Spectrophotometer | Measures pre-steady-state kinetics and KIEs on the millisecond timescale. | Instruments from Applied Photophysics, TgK Scientific. |

| FTIR with Stark Accessory | Measures vibrational frequencies and shifts under applied electric fields. | Bruker, Thermo Fisher; requires custom Stark cell. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Performs FEP calculations and analyzes electric fields (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER). | Open-source or commercial packages. |

| High-Dielectric Constant Buffers | Used in control experiments to screen electrostatic effects (e.g., high salt, cosolvents). | e.g., Potassium phosphate, NaCl. |

Probing the Invisible: Advanced Techniques to Measure, Model, and Harness Excited-State Catalysis

The study of enzyme catalysis has historically focused on ground-state transition-state stabilization. However, a frontier in biochemical research involves understanding the role of electronically excited states in enzymatic reactions. Non-adiabatic effects, charge transfer, and the manipulation of potential energy surfaces by the enzyme matrix may involve fleeting excited electronic configurations. The direct measurement of the intense, pre-organized electric fields within enzyme active sites provides a crucial link to this paradigm. The vibrational Stark effect (VSE) serves as a quantitative reporter of these fields, offering experimental insight into how electrostatic environments catalyze reactions, potentially by stabilizing excited-state intermediates or altering electronic transition barriers. This whiteprames the VSE as a foundational technique for probing the electrostatic framework that may govern both ground and excited-state chemistry in biological catalysis.

Theoretical Foundation: The Vibrational Stark Effect

The VSE describes the linear shift in the vibrational frequency (ν) of a chemical bond (typically a carbonyl or nitrile probe) in response to an external electric field (F). The relationship is given by:

Δν = -Δμ · F / hc

Where:

- Δν: Stark tuning rate (frequency shift per field, in cm⁻¹/(MV/cm)).

- Δμ: Difference in dipole moment between the ground and excited vibrational states (the Stark dipole, in Debye).

- F: External electric field vector (in MV/cm).

- h: Planck's constant.

- c: Speed of light.

In practice, the projection of the field along the probe's transition dipole axis is measured. Calibration in known solvents or synthetic constructs allows the conversion of measured frequency shifts into absolute electric field magnitudes.

Table 1: Representative VSE Calibration Data for Common Spectroscopic Probes

| Probe Molecule | Vibrational Mode | Stark Tuning Rate (Δν, cm⁻¹/(MV/cm)) | Δμ (Debye) | Typical Measurement Window (cm⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-Acetylbenzonitrile | C≡N Stretch | ~0.7 - 1.0 | ~0.2 - 0.3 | 2220 - 2250 |

| Methyl Thiocyanate | C≡N Stretch | ~0.4 - 0.6 | ~0.12 - 0.18 | 2150 - 2175 |

| Carbon Monoxide | C≡O Stretch | ~2.0 - 2.5 | ~0.6 - 0.75 | 1900 - 2100 |

| p-Nitrothiophenol | N-O Stretch (NO₂) | ~1.2 - 1.8 | ~0.35 - 0.55 | 1320 - 1350 |

Table 2: Reported Electric Fields in Selected Enzyme Active Sites via VSE

| Enzyme | Spectroscopic Probe | Reported Electric Field (MV/cm) | Inferred Contribution to Catalysis (ΔΔG‡, kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ketosteroid Isomerase | Carbonyl (¹³C=¹⁸O) | -140 to -160 | ~10 - 12 |

| Aldehyde Deformylating Oxygenase | Cyanide | ~+80 | ~6 - 8 |

| Artificial Metalloenzyme (Ir-CPI) | CO | -50 to -70 | ~4 - 5 |

| Class A β-Lactamase | Nitrile | ~+100 | ~7 - 9 |

Experimental Protocols

Probe Incorporation

A. Site-Directed Mutagenesis & Unnatural Amino Acid (UAA) Incorporation: This is the gold-standard for placing a Stark probe (e.g., a nitrile-functionalized phenylalanine) site-specifically.

- Plasmid Design: Engineer the gene of interest to replace the target active-site residue with an amber stop codon (TAG).

- Orthogonal tRNA/synthetase Pair: Co-express an engineered tRNA/synthetase pair specific for the desired UAA (e.g., p-Cyanophenylalanine) in the host cell (typically E. coli).

- Expression & Purification: Grow cells in media supplemented with the UAA. Induce protein expression. Purify the full-length, UAA-incorporated protein via affinity and size-exclusion chromatography.

- Verification: Confirm incorporation efficiency and protein integrity via ESI-MS.

B. Chemical Labeling: For surface sites or non-catalytic residues, a cysteine residue can be introduced via mutagenesis and labeled with a thiocyanate- or nitrile-containing maleimide reagent.

- Mutagenesis: Introduce a cysteine at the desired position.

- Reduction: Reduce the protein with TCEP to ensure free thiols.

- Labeling: Incubate with a 2-5x molar excess of the probe reagent for 2-4 hours at 4°C.

- Purification: Remove excess reagent using a desalting column or dialysis.

VSE Spectroscopy & Data Acquisition

Protocol for FTIR-based VSE Measurement:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare protein sample (~0.5-1 mM) in appropriate buffer (often low-ionic strength to prevent screening). Load into a demountable liquid cell with CaF₂ or BaF₂ windows and a defined pathlength (e.g., 50 µm).

- Instrument Setup: Use a high-sensitivity FTIR spectrometer (e.g., Bruker Vertex) equipped with a liquid N₂-cooled MCT detector. Purge the optical bench with dry air or N₂ to remove water vapor.

- Spectral Acquisition:

- Acquire a background spectrum (empty cell or buffer).

- Acquire 512-2048 scans of the protein sample at 2-4 cm⁻¹ resolution.

- For temperature control, use a circulating bath connected to the cell holder.

- Data Processing:

- Subtract buffer spectrum.

- Apply baseline correction (typically linear or polynomial).

- Fit the probe absorbance band (e.g., nitrile stretch) to a Gaussian or Voigt lineshape to determine the center frequency (ν₀) with high precision (±0.05 cm⁻¹).

External Field Calibration

Solvatochromic Calibration Protocol:

- Solvent Series: Dissolve the small-molecule analogue of the probe (e.g., methyl thiocyanate) in a series of 8-12 solvents spanning a wide range of known dielectric constants (e.g., hexane, dichloromethane, DMSO, water).

- Measurement: Record FTIR spectra for each solution as described in 4.2.

- Correlation: Plot the measured vibrational frequency (ν) against a reported solvent electrostatic parameter, typically the Local Dielectric Constant (ε) or the Empirical Polarity Parameter (Eₜ(30)).

- Calibration Curve: Perform a linear regression: ν = ν₀ + m * Field Parameter. The slope m is the empirical calibration factor (Stark tuning rate) for that specific probe in a similar molecular environment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for VSE Experiments

| Item | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Unnatural Amino Acid (UAA) e.g., p-Cyanophenylalanine | The core Stark probe. Its nitrile (–C≡N) group serves as the vibrational reporter sensitive to local electric fields. |

| Orthogonal Amber Suppressor tRNA/synthetase Plasmid Pair | Genetic tool for site-specific, ribosomal incorporation of the UAA into the protein in response to an amber (TAG) codon. |

| Maleimide-based Nitrile Probe (e.g., 4-Maleimidobenzonitrile) | Chemical labeling reagent for cysteine residues, used when UAA incorporation is not feasible. |

| CaF₂ or BaF₂ Optical Windows | Infrared-transparent windows for liquid sample cells. They are insoluble in water and transmit IR light in the key mid-IR region (1000-4000 cm⁻¹). |

| High-Sensitivity MCT (HgCdTe) Detector | Liquid nitrogen-cooled detector required for detecting the weak absorption signals of dilute protein samples in the IR. |

| FTIR Spectrometer with Dry Air/N₂ Purge System | The core instrument. Purging is critical to remove atmospheric CO₂ and H₂O vapor, which have strong, interfering IR absorptions. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns | For final protein purification and buffer exchange into a low-ionic strength, IR-compatible buffer (e.g., low concentration phosphate or MOPS). |

| TCEP-HCl (Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) | A reducing agent used to break protein disulfide bonds and maintain cysteine residues in a reduced, labelable state prior to chemical probing. |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: VSE Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: From Frequency Shift to Field Calculation

The investigation of electronically excited states is no longer confined to photochemistry or photobiology. A frontier thesis in modern enzyme catalysis posits that transient electronic excitations, often involving charge-transfer states or excited-state proton transfers, are critical mechanistic features in a growing class of enzymes. This paradigm challenges the traditional ground-state (GS) only view of biocatalysis. Mapping the complex, multi-dimensional landscapes of these excited states—their formation, evolution, and decay—requires computational methods that bridge quantum mechanics (QM) for electronic transitions and molecular mechanics (MM) for the biological environment. This guide details the integrated QM/MM and Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation framework essential for validating and exploring this transformative thesis.

Core Methodologies & Protocols

Multi-Scale QM/MM Simulation Protocol

Objective: To model the electronic excited-state landscape of a chromophore/substrate within its full protein-solvent environment.

System Preparation:

- Obtain the initial protein structure from PDB or a previous MD snapshot.

- Parameterize the ground state of the QM region (e.g., catalytic cofactor, substrate) using a density functional theory (DFT) method (e.g., ωB97X-D).

- Parameterize the MM region (protein, solvent, ions) using a standard force field (e.g., AMBER ff19SB, CHARMM36m).

- Solvate the system in a TIP3P water box, add neutralizing ions, and equilibrate with classical MD.

QM/MM Geometry Optimization & Dynamics:

- Define the QM region (30-100 atoms) and the MM region.

- Perform combined QM/MM geometry optimization of the ground state using an electrostatic embedding scheme.

- Run QM/MM Born-Oppenheimer Molecular Dynamics (BOMD) on the GS to sample thermal fluctuations.

Excited-State Mapping:

- At selected MD snapshots, perform QM/MM excited-state calculations.

- Use Time-Dependent DFT (TD-DFT) or Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF) methods for the QM region to compute vertical excitation energies, optimized excited-state (ES) geometries, and minimum energy paths (MEPs).

- Key analyses include:

- Frontier Molecular Orbitals involved in the transition.

- Potential Energy Surface (PES) scans along key reaction coordinates.

- Non-adiabatic coupling vectors for identifying funnel regions.

Non-Adiabatic Excited-State MD (NA-ESMD) Protocol

Objective: To simulate the real-time dynamics of electronic relaxation and energy flow after photoexcitation.

Initial Conditions:

- Generate an ensemble of initial structures from the ground-state QM/MM MD trajectory.

- For each snapshot, compute the excited-state of interest (e.g., S1) and its gradient.

Surface Hopping Dynamics:

- Employ the fewest-switches surface hopping algorithm (e.g., with SHARC or Newton-X interfaces).

- Propagate nuclei classically on the active potential energy surface.

- At each time step (∼0.5 fs), compute electronic wavefunction coefficients and hopping probabilities between coupled states based on non-adiabatic couplings.

- Perform hundreds to thousands of trajectories to gather statistically meaningful results.

Analysis:

- Compute time constants for internal conversion (IC) and intersystem crossing (ISC).

- Identify key molecular motions (e.g., bond rotations, solvation shell rearrangements) driving the relaxation.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of QM Methods for Excited-State Enzyme Simulations

| QM Method | Typical System Size (Atoms) | Computational Cost | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Best for... |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TD-DFT (e.g., ωB97X-D) | 50-150 | Moderate | Good accuracy/cost balance for singlet states; includes empirical dispersion. | Charge-transfer state errors; unreliable for double excitations or diradicals. | Initial screening of ES landscapes; large chromophores. |

| CASSCF/CASPT2 | 20-50 | Very High | Gold standard for multiconfigurational states; handles bond breaking, diradicals. | Exponential cost scaling; sensitive to active space selection. | Photoreactions, complex multi-electron transitions. |

| ADC(2) | 30-100 | High | More accurate than TD-DFT for many states; size-consistent. | Higher cost than TD-DFT; not for diffuse states. | Refined calculations of excitation energies and oscillator strengths. |

| DFTB | 100-1000 | Low | Enables nanosecond QM/MM MD. | Lower accuracy; parameter-dependent. | Long-timescale excited-state dynamics in large systems. |

Table 2: Key Observables from Recent QM/MM Studies of Excited-State Enzyme Catalysis

| Enzyme Class / System | Key Excited State Mapped | QM/MM Method Used | Key Quantitative Finding | Experimental Validation | Citation Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Photolyase | S1 (FADH¯) | QM(DFT)/MM MD | Charge separation lifetime: ∼50 ps; drives electron transfer to lesion. | Matches ultrafast spectroscopy data. | Paradigm for light-driven enzyme repair. |

| Protochlorophyllide Oxidoreductase (POR) | S1 & T1 (Substrate) | QM(CASSCF/CASPT2)/MM | Barrierless hydrogen transfer on S1; ISC rate ∼10¹² s⁻¹. | Consistent with fluorescence quenching & product analysis. | Key model for photobiocatalysis thesis. |

| Fluorescent Proteins (e.g., GFP) | S1 (Chromophore) | QM(TD-DFT)/MM PES Scan | Proton transfer barrier in S1: ∼3-5 kcal/mol, sensitive to electrostatic environment. | Correlates with emission spectra shifts in mutants. | Demonstrates protein tuning of ES landscape. |

Visualizing Workflows and Pathways

Title: QM/MM Workflow for Excited-State Mapping

Title: Key Photophysical Pathways in Enzyme Catalysis

The Scientist's Computational Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for QM/MM ES Simulations

| Tool / "Reagent" | Category | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER, CHARMM, GROMACS | MM Force Field / MD Engine | Provides the classical MM framework for simulating protein dynamics. Essential for equilibration and sampling conformational ensembles before QM treatment. |

| Gaussian, ORCA, PySCF | QM Electronic Structure Package | Performs the core quantum chemical calculations (TD-DFT, CASSCF) to compute ground and excited-state energies, gradients, and properties for the QM region. |

| Q-Chem, TeraChem | High-Performance QM Package | Specialized for accelerated QM calculations, often with GPU support, enabling larger QM regions or faster dynamics for ES mapping. |

| ChemShell, fDynamo | QM/MM Integration Platform | Manages the coupling between the QM and MM regions, handling energy and force partitioning, and enabling geometry optimizations and MD in a unified framework. |

| SHARC, Newton-X | Non-Adiabatic Dynamics Interface | Implements surface hopping algorithms. Takes initial conditions and electronic structure data to simulate excited-state population transfer and decay dynamics. |

| CP2K, DFTB+ | Semi-Empirical / DFTB MD | Enables extended timescale QM/MM MD using faster, approximate QM methods, useful for sampling rare events or long relaxation processes on ES landscapes. |

| VMD, PyMOL, Jupyter | Visualization & Analysis Suite | Critical for inspecting structures, plotting PESs, analyzing orbitals, and creating publication-quality figures of simulation results. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Infrastructure | The essential "hardware reagent". QM/MM and NA-ESMD calculations are computationally intensive, requiring access to parallel CPU/GPU clusters for production runs. |

This technical guide synthesizes current research on the extended chemical environment of enzyme active sites, framed within the broader investigation of electronically excited states in enzymatic catalysis. The protein scaffold and second coordination sphere—residues, hydrogen-bonding networks, and electrostatic interactions surrounding the primary catalytic site—are critical for modulating reaction dynamics, including the stabilization of non-ground-state species. This whitepale provides methodologies and data for researchers aiming to deconvolute these complex contributions, with direct relevance to the rational design of biocatalysts and novel therapeutic inhibitors.

The study of electronically excited states in enzymes, such as those involved in photoreceptor function, radical initiation, or long-range electron transfer, extends beyond the chromophore or active site metals. The protein matrix dictates the energetic landscape, influencing excited-state lifetimes, charge transfer efficiencies, and the propensity for nonadiabatic crossings. This document examines how the second coordination sphere and overall scaffold architecture are engineered to control these photophysical and photochemical pathways, offering a roadmap for experimental interrogation.

Core Concepts and Quantitative Data

Key Interactions of the Second Coordination Sphere

The second coordination sphere comprises structural elements that do not directly bind the substrate but are essential for function.

Table 1: Types and Impacts of Second Coordination Sphere Interactions

| Interaction Type | Typical Distance Range | Proposed Role in Excited-State Catalysis | Exemplar Enzyme/System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen-Bonding Network | 1.5 – 3.2 Å | Tunes redox potentials; gates proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET); stabilizes charge-separated states. | Photosystem II, Cytochrome c Oxidase |

| Electrostatic (Salt Bridges, Dipoles) | 3 – 6 Å | Modulates electric fields at the active site; influences excited-state dipole moments and emission spectra. | Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP), Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| Hydrophobic Packing | 3.5 – 6 Å | Creates cavities with specific dielectric constants; controls substrate orientation and access to reactive conformations. | P450 Monooxygenases, Luciferase |

| Remote Acid/Base Residues | 4 – 10 Å | Participates in long-range proton relay, essential for quenching excited states or forming reactive intermediates. | Bacteriorhodopsin, DNA Photolyase |

Experimental Metrics for Scaffold Analysis

Quantitative measures link scaffold properties to catalytic parameters, including those relevant to excited-state dynamics.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Protein Scaffold Impact Analysis

| Metric | Measurement Technique | Correlation with Catalytic Function | Example Value Range (from literature) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reorganization Energy (λ) | Electrochemistry, Stark Spectroscopy | Lower λ in engineered scaffolds enhances electron transfer rates. | 0.5 – 1.2 eV (for optimized systems) |

| Electric Field Strength | Vibrational Stark Effect Spectroscopy | Field strength > 50 MV/cm can significantly alter transition state energies. | 10 – 150 MV/cm |

| Dielectric Constant (local, ε) | Molecular Dynamics Simulation | Low ε (~4) in hydrophobic pockets stabilizes charge-separated excited states. | 4 – 40 (protein interior vs. water) |

| Conformational Dynamics Timescale | NMR Relaxation, FCS | Fast dynamics (ns-µs) often correlate with efficient quenching or energy transfer. | Picoseconds to milliseconds |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Mapping Electric Fields via Vibrational Stark Effect (VSE) Spectroscopy

Objective: Quantify the magnitude and direction of the intrinsic electric field within an enzyme's active site.

- Site-Specific Probe Incorporation: Introduce a non-natural amino acid (e.g., p-cyanophenylalanine) or a carbon-deuterium bond vibration as a field-sensitive reporter via mutagenesis and/or chemical synthesis.

- Sample Preparation: Purify the modified enzyme in a stable, catalytically relevant state. For frozen samples, prepare in a suitable cryoprotectant buffer.

- FTIR or Raman Acquisition: Collect high-resolution infrared or Raman spectra of the probe vibration.

- External Field Application: Place the sample in a capacitor cell and acquire spectra under applied external electric fields (typically 0 – 5 × 10^5 V/cm).

- Stark Effect Analysis: Plot the shift in vibrational frequency (Δν) vs. the square of the applied field strength (E²). The slope yields the Stark tuning rate (Δμ, the change in dipole moment). The internal field is inferred from the probe's frequency shift relative to a solvent-exposed reference state.

Protocol: Assessing Long-Range Proton Coupling via Kinetic Isotope Effect (KIE) Profiling

Objective: Identify residues involved in long-range proton transfer during catalysis, a key component of many excited-state reaction cycles.

- Systematic Mutagenesis: Construct alanine (or conservative) substitution mutants of all polar/charged residues within a 10-15 Å radius of the active site cofactor.

- Activity Assays under Isotopic Solvent: Measure the catalytic turnover number (k_cat) for wild-type and mutant enzymes in both H₂O and D₂O-based buffers.

- KIE Calculation: Compute the solvent kinetic isotope effect (SKIE) as kcat(H₂O)/*k*cat(D₂O) for each variant.

- Data Interpretation: Residues whose mutation causes a significant attenuation of the SKIE (e.g., from 4 to near 1) are implicated in a rate-limiting proton transfer pathway. Complementary pKₐ shift analysis of the mutants can confirm the proton relay network.

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Diagram Title: Scaffold Modulation of Excited-State Pathways

Diagram Title: VSE Spectroscopy Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Second Coordination Sphere Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Example Vendor/Product Code |

|---|---|---|

| Non-natural Amino Acid Kits | For site-specific incorporation of vibrational or fluorescent probes (e.g., p-CN-Phe, Azido-Lys). | Click Chemistry Tools; Genscript SOLARIS. |

| Deuterated Substrates/Solvents | For probing proton transfer pathways via KIEs (e.g., D₂O, CH₃CD₂- precursors). | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories; Sigma-Aldrich. |

| QuikChange or Gibson Assembly Kits | For rapid site-directed mutagenesis to test putative second-sphere residues. | Agilent; NEB HiFi DNA Assembly. |

| Electric Field Cell (Stark Cell) | Capacitor cell for applying high external electric fields to protein samples. | Custom from PiKem or Harrick Scientific. |

| Stable Isotope Labeled Growth Media (¹⁵N, ¹³C) | For advanced NMR characterization of protein dynamics and hydrogen bonding. | Silantes; Isotec. |

| Computational Software Licenses | For MD simulations and QM/MM calculations of electric fields and excited states (e.g., Gaussian, GROMACS, CHARMM). | Schrodinger; Open Source. |

| Cryotrapping Stopped-Flow Apparatus | To trap and characterize transient excited-state intermediates. | Applied Photophysics SX20; TgK Scientific. |

Recent research in enzyme catalysis has expanded beyond ground-state thermodynamics to incorporate the critical role of electronically excited states. This paradigm shift, central to our broader thesis, recognizes that transient photophysical and photochemical events—such as charge transfer, radical pair formation, and vibronic coupling—can be integral to catalytic mechanisms, even in non-photoactive enzymes. Rational enzyme design must now account for these quantum phenomena. This guide details how computational and experimental insights into excited-state dynamics inform two cutting-edge strategies: the de novo creation of enzymes from first principles and the functional repurposing of existing protein scaffolds.

Foundational Concepts: Excited States in Catalysis

Key electronically excited-state phenomena relevant to enzyme design include:

- Charge-Transfer Complexes: Donor-acceptor pairs that stabilize transition states via transient electronic redistribution.

- Biradical/Quinoid Intermediates: High-energy intermediates stabilized within enzyme active sites, relevant for mechanisms involving homolytic bond cleavage.

- Vibronic Coupling: The interaction between electronic and nuclear motions, influencing reaction coordinate traversal and catalytic efficiency.

- Conical Intersections: Degeneracies between potential energy surfaces that can facilitate ultra-fast non-radiative decay, steering product selectivity.

Computational Toolkit for Excited-State-Aware Design

Key Methodologies

- Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM): Essential for modeling bond-breaking/forming events in their protein environment. Excited-state QM/MM (e.g., TD-DFT/MM) maps photophysical landscapes.

- Non-Adiabatic Molecular Dynamics (NAMD): Simulates transitions between electronic states, critical for predicting outcomes post-excitation.

- Machine Learning (ML) Potentials: Trained on QM data, they enable rapid screening of sequence space for excited-state properties.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Tool | Function in Excited-State Enzyme Design |

|---|---|

| Rosetta (with QM extensions) | Protein modeling suite adapted to incorporate quantum-derived energetic terms for active site design. |

| CHARMM/AMBER with PLUMED | MD force fields with enhanced sampling plugins to probe rare events linked to excited-state crossings. |

| Gaussian, ORCA, or CP2K | QM software for calculating ground and excited-state potential energy surfaces of catalytic motifs. |

| DeepMind AlphaFold 3 | Predicts protein-ligand structures, providing starting points for QM/MM analysis of bound states. |

| Non-Natural Amino Acids (e.g., pCNF) | Enable spectroscopic probes (e.g., Stark spectroscopy) or introduce novel redox/photo-properties into scaffolds. |

| Transient Absorption/FTIR Spectrometers | Monitor ultrafast (fs-µs) kinetics and structural changes following laser excitation of designed enzymes. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating Excited-State Contributions

Protocol: Time-Resolved Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (TR-SFX) at an XFEL Aim: Capture geometric and electronic changes in a designed enzyme during catalysis at atomic resolution and on femtosecond timescales.

- Sample Preparation: Purified engineered enzyme is co-crystallized with substrate (or photo-caged substrate). Microcrystals (<10 µm) are suspended in a compatible buffer for injection.

- Photo-Triggering: A femtosecond laser pulse (wavelength tuned to substrate or enzyme chromophore absorption) synchronously initiates the catalytic reaction within the crystal.

- Data Collection: The crystal suspension is injected across the X-ray Free Electron Laser (XFEL) beam. Each crystal is destroyed upon exposure, but the diffraction "snapshot" is collected before destruction.

- Time Delay Series: The delay between the photo-triggering laser and the XFEL pulse is systematically varied (from fs to ms).

- Data Analysis: Millions of diffraction patterns are assembled into a movie of electron density changes, revealing the formation and decay of excited-state species and intermediates.

Quantitative Data on Design Strategies

Table 1: Comparison of De Novo Design vs. Scaffold Repurposing

| Parameter | De Novo Creation | Scaffold Repurposing |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Create a novel fold/active site for a non-natural or engineered reaction. | Adapt an existing, stable fold for a new catalytic function. |

| Typical Starting Point | Theoretically ideal transition state geometry (from QM). | Known protein structure (e.g., from PDB) with desired structural features. |

| Excited-State Consideration | Designed ab initio into the active site quantum landscape. | Must be engineered into a pre-existing electronic environment. |

| Computational Cost | Extremely High (full fold search + active site design). | Moderate to High (focused on active site and substrate channel redesign). |

| Success Rate (Reported) | Low (<1% for novel reactions) but increasing with ML. | Higher (5-20%), depending on functional distance from native role. |

| Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/KM) | Often 10² - 10⁴ M⁻¹s⁻¹ in best cases. | Can approach 10⁵ - 10⁶ M⁻¹s⁻¹ if repurposing is minimal. |

| Key Challenge | Achieving functional dynamics and long-range electrostatics. | Overcoming latent evolutionary constraints on the scaffold's reactivity. |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Recently Designed Enzymes with Excited-State Features

| Enzyme / Design Strategy | Target Reaction | Key Excited-State Feature Engineered | Rate Enhancement (vs. uncat.) | Turnover Number (min⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kemp Eliminase (HG-3) / De Novo | Kemp elimination | Stabilization of anionic transition state via designed charge relay. | 10⁶ | ~ 2.6 x 10² |

| Light-Oxygen-Voltage (LOV) scaffold repurposing | Asymmetric C-H activation | Harnessing native flavin triplet excited state for H-atom abstraction. | 10⁸ (photo-driven) | ~ 3.0 x 10³ |

| Computationally repurposed hydrolase | Aza-electrocyclization | Designed to stabilize a polarized, charge-transfer-like cyclic transition state. | 10⁷ | ~ 1.9 x 10² |

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram Title: Rational enzyme design workflow informed by excited-state thesis

Diagram Title: TR-SFX protocol for probing excited-state dynamics

Future Outlook

The integration of excited-state theory into rational design marks a transition from a static, ground-state view of enzymes to a dynamic, quantum-aware one. As computational power and experimental techniques like TR-SFX mature, the deliberate engineering of electronic excited states will become a standard tool for creating enzymes for novel chemistry, asymmetric synthesis, and next-generation therapeutics.

This case study is situated within a broader thesis investigating the role of electronically excited states in enzyme catalysis. While traditional mechanistic studies focus on ground-state thermodynamics and transition-state theory, emerging research highlights the potential for photoexcited or charge-transfer states to influence reaction pathways and selectivity in biological systems. Predicting stereoselectivity—a critical factor in drug development—from pre-reaction geometries presents a significant challenge. This guide explores how machine learning (ML) models, trained on quantum chemical data, can bypass the need for full transition-state characterization and predict enantioselective outcomes directly from more accessible pre-reaction state geometries. This approach offers a rapid computational tool that could eventually integrate excited-state electronic structure data to predict novel photocatalytic or enzymatic stereoselective transformations.

Core Machine Learning Methodology

The primary goal is to train ML models to predict enantiomeric excess (ee) or the differential activation energy (ΔΔG‡) using only features derived from the geometries of reactant(s) and catalyst in a pre-reaction complex.

Data Generation Protocol

Quantum Chemical Calculations:

- Software: Gaussian 16, ORCA, or PSI4.

- System Preparation: Generate a diverse set of substrate-catalyst pre-reaction complexes for a given asymmetric reaction (e.g., propargylation, aldol addition).

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize all pre-reaction complex geometries using Density Functional Theory (DFT) with a functional like B3LYP and basis set 6-31G(d).

- Transition State Location: For the same complexes, locate and verify the corresponding diastereomeric transition states (TS) using TS optimization algorithms (e.g., QST2, QST3) and confirm with frequency calculations (one imaginary frequency).

- Energy Calculation: Perform higher-level single-point energy calculations (e.g., DLPNO-CCSD(T)/def2-TZVP) on both pre-reaction and TS geometries to compute the activation barrier (ΔG‡) for each pathway.

- Target Variable: Calculate the stereoselectivity predictor: ΔΔG‡ = ΔG‡(TSMajor) - ΔG‡(TSMinor).

Feature Engineering from Pre-Reaction Geometry:

- Descriptors: From the optimized pre-reaction complex only, compute:

- Distances: Key interatomic distances (e.g., between reacting atoms, catalyst control points).

- Angles & Dihedrals: Critical bond angles and torsion angles defining the chiral environment.

- Partial Atomic Charges: From Natural Population Analysis (NPA) or Hirshfeld partitioning.

- Steric Parameters: Sterimol parameters (B1, B5, L) for substituents.

- Molecular Descriptors: Using RDKit (for organic fragments): number of rotatable bonds, topological polar surface area.

- Quantum Mechanical Descriptors: HOMO/LUMO energies of the complex, molecular dipole moment.

- Descriptors: From the optimized pre-reaction complex only, compute:

Model Training & Validation

- Dataset Splitting: 70/15/15 split for training, validation, and held-out test sets. Scaffold splitting is used to ensure generalization to new core structures.

- Model Architectures:

- Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR): Baseline model using smooth overlap of atomic positions (SOAP) descriptors.

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Directed Message Passing Neural Networks (D-MPNNs) operate directly on molecular graphs of the pre-reaction complex.

- 3D Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): Utilize voxelized electron density or steric field maps generated from the 3D geometry.

- Performance Metric: Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) on predicting ΔΔG‡ (in kcal/mol) or direct ee (%) on the test set.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of ML Models on Stereoselectivity Prediction

| Model Type | Descriptor Input | Test Set RMSE (ΔΔG‡, kcal/mol) | Test Set MAE (ee, %) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kernel Ridge Regression | SOAP Vectors | 0.85 | 12.5 | Interpretability, small datasets |

| Directed MPNN | Molecular Graph (2D/3D) | 0.62 | 8.7 | Learns directly from structure |

| 3D-CNN | Electron Density Grid | 0.71 | 10.2 | Captures implicit 3D electronic effects |

| Random Forest | Combined Steric/Electronic | 0.95 | 14.1 | Fast inference, robust to noise |

Table 2: Key Computational Results from Representative Study

| Reaction Class | # Pre-Reaction Complexes | Best Model | Predicted ΔΔG‡ Range | Experimental ee Range | Correlation (R²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asymmetric Propargylation | 245 | D-MPNN | -2.1 to 3.4 kcal/mol | 90% to 99% (S) | 0.89 |

| Enantioselective Aldol | 187 | 3D-CNN | -1.8 to 2.9 kcal/mol | 80% to 95% (R) | 0.82 |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for ML-Driven Prediction

Protocol: Building a D-MPNN for Stereoselectivity Prediction

Input Data Preparation:

- Generate SMILES strings or 3D coordinate files (.xyz) for each substrate-catalyst pre-reaction complex.

- Label each complex with its experimentally or computationally derived ΔΔG‡ or ee value.