Homogeneous vs. Heterogeneous Catalysis: A Comparative Analysis for Advanced Research and Drug Development

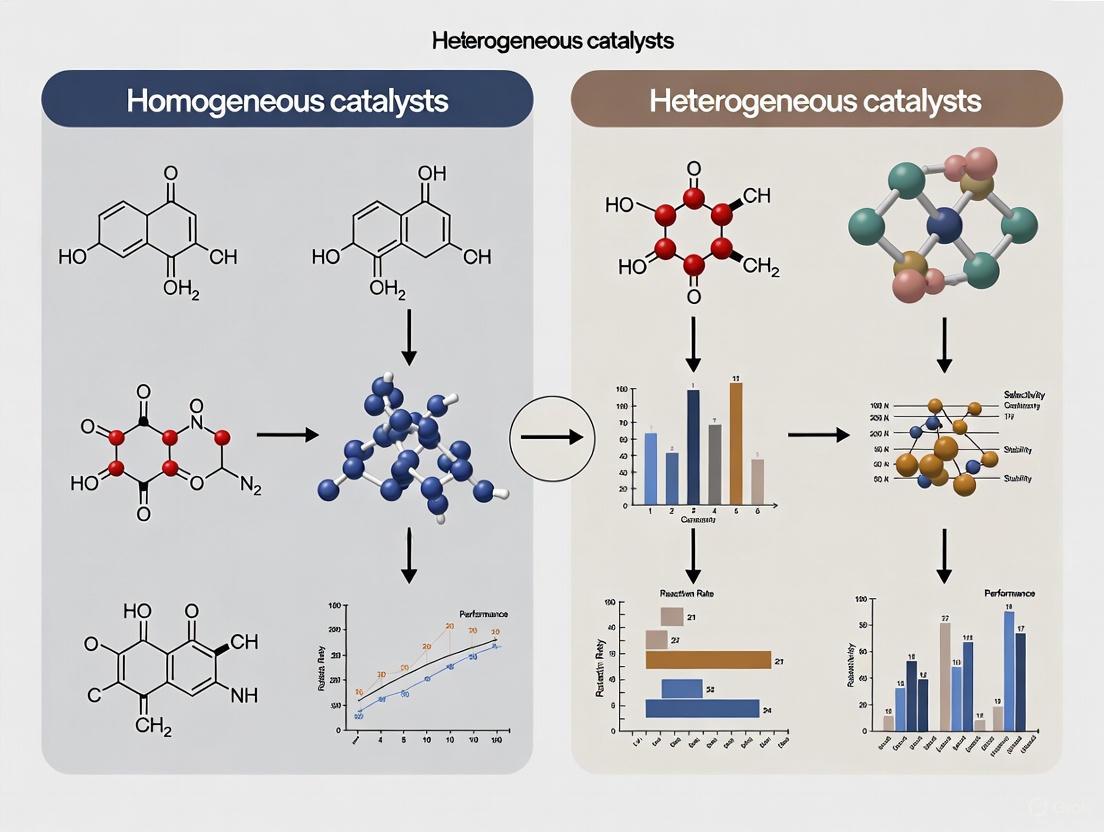

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of homogeneous and heterogeneous catalyst performance, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Homogeneous vs. Heterogeneous Catalysis: A Comparative Analysis for Advanced Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of homogeneous and heterogeneous catalyst performance, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles, phase behavior, and active site interactions that define each catalyst type. The scope extends to methodological applications across pharmaceuticals, fine chemicals, and environmental remediation, highlighting real-world use cases and efficiency metrics. The content further addresses key challenges in troubleshooting, optimization, and catalyst recovery, offering strategies to enhance performance and longevity. Finally, a rigorous validation framework compares selectivity, activity, and separation efficiency, synthesizing insights to guide catalyst selection for innovative and sustainable biomedical research.

Core Principles: Defining Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalysis

Fundamental Definitions and Phase Relationships

Catalysis is a foundational concept in chemical synthesis, defined by three principal features: the acceleration of chemical reaction rates, invariance of the thermodynamic equilibrium composition, and the catalyst itself not being consumed during the reaction process [1]. The widely accepted mechanistic basis for catalytic action is the lowering of the activation energy barrier through specific interactions between reactants and catalytic centers [1]. Catalytic systems are fundamentally classified based on the phase relationship between the catalyst and reactants, with homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis representing the two primary categories [1].

In homogeneous catalysis, the catalyst and reactants exist in the same phase, typically liquid, allowing for intimate molecular interaction and often resulting in high activity and selectivity [1]. In contrast, heterogeneous catalysis involves catalysts and reactants in different phases, usually solid catalysts interacting with gaseous or liquid reactants, facilitating easier separation and potential catalyst reuse [1]. A rapidly growing area is Single-Atom Catalysis (SAC), where isolated metal atoms anchored to solid supports act as well-defined active catalytic centers, blurring the traditional boundaries between homogeneous and heterogeneous systems [1].

This guide provides an objective comparison of these catalytic approaches, focusing on their fundamental definitions, phase relationships, and performance characteristics relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Definitions and Phase Characteristics

Core Definitions and Classifications

Homogeneous Catalysis involves a catalyst that exists in the same phase as the reactants, most commonly in the liquid phase [1]. The catalytic species, often molecular organometallic complexes or distinct chemical moieties, are uniformly dispersed among the reactant molecules, enabling all catalytic sites to be potentially accessible for reaction [1]. Gas-phase homogeneous catalysis is rare but exemplified by the oxidation of SO₂ to SO₃ using nitrogen oxides [1].

Heterogeneous Catalysis employs a catalyst in a different phase from the reactants, typically solid catalysts interacting with gaseous, vapor, and/or liquid reactants [1]. Reactions proceed on catalytic centers represented by specific chemical moieties or structural features of solid materials, such as edges, corners, steps, and vacancies, which locally alter surface energy [1].

A noteworthy hybrid class is heterogenized catalysts, where homogeneous active moieties (e.g., organometallic complexes, specific functional groups) are chemically bonded to organic polymers or inorganic supports [1]. These systems combine molecular precision with practical separation advantages.

Expanded Catalytic Classifications

With advances in catalytic science, additional classifications have emerged based on external energy inputs and activation mechanisms [1]:

- Electrocatalysis: Utilizes electrical energy to drive reactions at electrode surfaces [1].

- Photocatalysis: Employs photon energy, typically from light, to excite catalytic species [2].

- Microwave Catalysis: Uses microwave radiation to selectively heat catalysts or reactants [1].

- Sonocatalysis: Applies ultrasonic energy to enhance catalytic activity [1].

- Mechanocatalysis: Relies on mechanical forces to induce catalytic transformations [1].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Catalytic Systems

| Characteristic | Homogeneous Catalysis | Heterogeneous Catalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Phase Relationship | Catalyst and reactants in same phase (typically liquid) [1] | Catalyst and reactants in different phases (typically solid catalyst with liquid/gas reactants) [1] |

| Catalytic Center | Molecular species (organometallic complexes, functional groups) uniformly dispersed [1] | Surface sites (edges, corners, vacancies) or supported nanoscale structures [1] |

| Active Site Uniformity | High - essentially all active sites are identical [1] | Variable - sites may differ in geometry and energy [1] |

| Typical Examples | Organometallic complexes in solution, enzymes [1] | Metal nanoparticles on supports, zeolites, metal-organic frameworks [1] |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Activity, Selectivity, and Stability

The choice between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis involves complex trade-offs across multiple performance dimensions. Homogeneous catalysts typically offer superior activity under mild conditions and excellent selectivity, particularly for enantioselective transformations, due to their well-defined, uniform active sites [1]. However, they present significant challenges in catalyst separation and recovery, often leading to metal contamination in products and limited operational lifetime [1] [2].

Heterogeneous catalysts provide inherent advantages in separation efficiency, enabling continuous operation and straightforward catalyst reuse [1]. They generally exhibit greater thermal stability and longer operational lifetimes, though they often require higher temperatures and pressures to achieve satisfactory activity [1]. Mass transport limitations can reduce effective reaction rates, while selectivity may be compromised due to the heterogeneity of active sites [1].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Catalytic Systems

| Performance Metric | Homogeneous Catalysis | Heterogeneous Catalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic Activity | Typically high under mild conditions [1] | Often requires higher temperatures/pressures [1] |

| Selectivity Control | Excellent, especially for enantioselective reactions [1] | Variable, site heterogeneity can reduce selectivity [1] |

| Catalyst Separation | Difficult, requiring complex processes [1] | Straightforward, via filtration or simple settling [1] |

| Thermal Stability | Generally moderate to low [1] | Typically high [1] |

| Operational Lifetime | Often limited by decomposition [1] | Generally longer, often regenerable [1] |

| Mass Transport Effects | Minimal (single phase) [1] | Often significant, affecting observed kinetics [1] |

Applications in Chemical Synthesis and Energy

Both catalytic approaches find extensive applications across chemical synthesis, energy production, and environmental protection. Heterogeneous catalysts dominate industrial-scale processes such as petroleum refining (fluid catalytic cracking), chemical production (ammonia synthesis, methanol production), and environmental catalysis (automotive exhaust treatment) [1] [3]. The global heterogeneous catalyst market was valued at USD 23.6 billion in 2023, with chemical synthesis applications accounting for the largest share (26.3%), followed by petroleum refining as the fastest-growing segment [3].

Homogeneous catalysts excel in specialized chemical synthesis, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry where their high selectivity enables efficient production of complex molecules, including Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) [2]. Recent advances integrate homogeneous catalysis with continuous flow systems, photocatalysis, and electrocatalysis to overcome traditional limitations and unlock novel synthetic pathways [2].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Catalyst Characterization Framework

Comprehensive catalyst characterization employs six main groups of physicochemical parameters [1]:

- Chemical composition and crystallographic structure - Determining elemental makeup and atomic arrangement

- Texture and physical-chemical properties - Analyzing surface area, porosity, and morphology

- Temperature and chemical stability - Assessing durability under operational conditions

- Mechanical stability - Evaluating resistance to attrition and crushing

- Mass, heat, and electrical transport properties - Measuring diffusion characteristics and thermal conductivity

- Catalytic performance - Testing activity, selectivity, and lifetime under reaction conditions

Protocol: Comparative Hydrogenation Activity

Objective: Compare the catalytic performance of homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts for substrate hydrogenation.

Materials:

- Homogeneous catalyst: Transition metal complex (e.g., RhCl(PPh₃)₃)

- Heterogeneous catalyst: Metal nanoparticles on support (e.g., Pd/C)

- Substrate: Appropriate unsaturated compound (e.g., alkene, carbonyl)

- Solvent: Suitable for both catalytic systems (e.g., ethanol, toluene)

- Hydrogen source: H₂ gas cylinder with pressure regulation

Experimental Setup:

- Reactor System: Use parallel pressurized batch reactors or continuous flow microreactors equipped with temperature control, pressure monitoring, and sampling ports [2].

- Safety Measures: Implement hydrogen detection, pressure relief devices, and appropriate ventilation.

Procedure:

- Charge reactor with catalyst (0.1-1 mol% metal for homogeneous; 1-5 wt% for heterogeneous) and substrate solution.

- Purge system with inert gas (N₂ or Ar) to remove oxygen.

- Pressurize with H₂ to predetermined pressure (1-50 bar).

- Initiate reaction with stirring/flow and maintain at constant temperature.

- Collect periodic samples for analysis.

- For homogeneous system: After reaction, attempt catalyst recovery via solvent extraction or distillation.

- For heterogeneous system: After reaction, separate catalyst via filtration, wash, and dry for potential reuse testing.

Analysis:

- Conversion: Quantify substrate consumption via GC, HPLC, or NMR.

- Selectivity: Determine product distribution using calibrated analytical methods.

- Kinetics: Calculate turnover frequency (TOF) based on active sites.

- Catalyst Stability: Compare metal leaching (ICP-MS), structural changes (XRD, XPS), and activity in recycle experiments.

Advanced Integration with Flow Chemistry

Continuous flow systems represent a paradigm shift for implementing catalytic processes, particularly benefiting homogeneous catalysis through [2]:

- Enhanced mass/heat transfer superior to traditional batch processes

- Precise parameter control (temperature, pressure, residence time)

- Safer operation under extreme conditions (high T/P)

- Seamless integration of Process Analytical Technology (PAT) for real-time monitoring

- Predictable scale-up through numbering-up or smart dimensioning strategies

The integration of homogeneous catalysis with continuous flow systems enables the practical implementation of photoredox catalysis and electrocatalysis, overcoming traditional limitations in scale-up and process control [2].

Visualization of Catalytic Relationships

Diagram 1: Catalyst System Selection Workflow. This decision pathway illustrates the logical process for selecting between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalytic systems based on phase relationships and application requirements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Catalytic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Complexes (e.g., Rh, Pd, Ru complexes) | Serve as homogeneous catalysts/precursors with well-defined active sites [1] | Provide high activity and selectivity; require careful handling under inert atmosphere |

| Supported Metal Catalysts (e.g., Pd/C, Pt/Al₂O₃) | Heterogeneous catalysts with metal nanoparticles on high-surface-area supports [1] | Facilitate easy separation; metal leaching can be concern in some applications |

| Zeolites | Crystalline microporous aluminosilicates with shape-selective properties [4] [1] | Excellent for acid-catalyzed reactions and size-selective catalysis; used in refining and chemicals |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Porous materials with ultrahigh surface area and tunable functionality [4] | Emerging materials for specialized applications; thermal and chemical stability varies |

| Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) | Isolated metal atoms on supports bridging homogeneous/heterogeneous catalysis [1] | Maximize metal utilization; stability under reaction conditions can be challenging |

| Ionic Liquids | Low-melting salts serving as solvents or functional reaction media [4] | Enable catalyst immobilization; tunable polarity and solvation properties |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | Inline/online analytical tools (FTIR, HPLC) for real-time reaction monitoring [2] | Critical for kinetic studies and reaction optimization in flow systems |

In the pursuit of efficient and sustainable chemical processes, the choice between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis is fundamental. This guide provides an objective comparison of two principal mechanistic pathways: the Langmuir-Hinshelwood (L-H) mechanism, characteristic of heterogeneous catalysis, and the pathway involving homogeneous intermediate complexes, central to homogeneous catalysis. The performance of these systems is evaluated based on activity, selectivity, kinetic behavior, and practical applicability, with a focus on providing researchers and development professionals with supporting experimental data and methodologies.

The core distinction lies in the catalyst's phase and the resulting reaction mechanism. In heterogeneous L-H kinetics, reactants adsorb onto a solid surface before reacting, while in homogeneous catalysis, the catalyst and reactants form intermediate complexes within a single phase. Understanding these differences is critical for selecting the appropriate catalytic system for specific applications, from bulk chemical production to fine chemical and pharmaceutical synthesis.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Kinetic Profiles

The Langmuir-Hinshelwood Mechanism

The Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism describes a surface reaction where two adsorbed species react with each other on the catalyst surface. The key principle is that the reaction rate is governed by the surface coverage of each reactant, which is typically described by Langmuir-type adsorption isotherms [5].

- Mechanism Steps: The mechanism involves multiple steps: (1) adsorption of reactants onto the active sites of the catalyst surface, (2) surface reaction between the adjacent adsorbed species to form the product, and (3) desorption of the product from the surface to regenerate the active sites [5]. For a single reactant A, the steps are:

A + S → A_a(Adsorption)A_a → A + S(Desorption)A_a → S + P(Surface Reaction) whereSis an active site andA_ais the adsorbed A species [6]. - Kinetic Equation: For a bimolecular reaction, the rate expression is often complex, but for a monomolecular reaction where the surface reaction is the rate-determining step, the kinetics can be simplified to:

r = (k K C) / (1 + K C)whereris the reaction rate,kis the surface reaction rate constant,Kis the adsorption equilibrium constant, andCis the substrate concentration [5]. - Validation: Proof of the L-H mechanism requires not only that the kinetic data fits this equation but also that the adsorption equilibrium constant

Kobtained from kinetic data matches the value determined from independent dark adsorption measurements [5].

Homogeneous Intermediate Complex Mechanism

In homogeneous catalysis, the catalyst and reactants exist in the same phase, typically a liquid. The mechanism proceeds through the formation of discrete, soluble intermediate complexes.

- Mechanism Steps: The process generally involves (1) coordination of the reactant to the metal center of the catalyst, forming a complex, (2) transformation of the ligand (e.g., insertion, rearrangement) within the coordination sphere to form the product complex, and (3) release of the product and regeneration of the catalyst.

- Kinetic Profile: The kinetics are typically described by the Michaelis-Menten model, which is functionally similar to the L-H equation but operates in a single phase. The rate is proportional to the concentration of the catalyst-substrate complex.

- Distinguishing Feature: A key differentiator from heterogeneous mechanisms like Eley-Rideal is that in homogeneous catalysis, the reacting molecules are both coordinated to the catalyst metal center before the key bond-forming/breaking event occurs.

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in the mechanistic pathways.

Comparative Performance Analysis

The choice between L-H and homogeneous mechanisms has profound implications for catalytic performance. The table below summarizes key comparative metrics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of L-H Heterogeneous and Homogeneous Catalytic Systems

| Performance Metric | Langmuir-Hinshelwood (Heterogeneous) | Homogeneous Intermediate Complex |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Activity | Variable; can be high but often limited by mass transfer to the surface [5] | Often very high due to uniform accessibility of all catalytic sites |

| Selectivity | Can be high; dependent on surface structure and pore geometry | Typically high and tunable via ligand design |

| Kinetic Profile | Follows Langmuir-type kinetics; rate often decreases at high concentrations due to site saturation [5] | Often follows Michaelis-Menten kinetics |

| Catalyst Stability | Generally high; solid catalyst is robust and sinter-resistant | Can be lower; susceptibility to thermal decomposition and deactivation |

| Reaction Conditions | Often requires elevated temperatures for sufficient surface reaction rates | Can frequently operate under milder conditions |

| Sepovability & Reuse | Excellent; simple filtration allows for full recovery and reuse [7] | Difficult and expensive; often requires complex processes like distillation |

| Applicability | Broad; used in large-scale continuous processes (e.g., DMC synthesis [8], Hg0 oxidation [5]) | Broad; ideal for fine chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and asymmetric synthesis |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

High-Throughput Screening for Homogeneous Catalysts

Modern catalyst discovery, particularly for homogeneous systems, leverages high-throughput experimentation (HTE) for rapid optimization.

- Platform: A fluorogenic system in a 24-well plate format enables simultaneous monitoring of multiple reactions [7].

- Reaction Probe: The reduction of a nitronaphthalimide (NN) probe to a fluorescent amine (AN) serves as a model reaction (e.g., for catalyst screening in nitro-to-amine reduction) [7].

- Procedure: Each reaction well contains catalyst, NN probe, and reagents (e.g., aqueous N2H4). A paired reference well contains the product (AN) instead of NN to provide a fluorescence standard. The plate is placed in a multi-mode reader, which performs orbital shaking and then scans fluorescence and absorption spectra at set intervals (e.g., every 5 minutes for 80 minutes) [7].

- Data Analysis: The decay of the NN absorbance peak (350 nm) and the growth of the AN absorbance (430 nm) and fluorescence (ex. 485 nm / em. 590 nm) provide conversion and kinetic data. The stability of the isosbestic point (e.g., 385 nm) indicates a clean conversion without significant side products [7].

Kinetic Model Verification for L-H Mechanisms

Verifying an L-H mechanism requires more than just kinetic fitting; it involves a rigorous multi-step process.

- Kinetic Data Fitting: Initial rate data is fitted to a linearized form of the L-H equation, such as a plot of the reciprocal rate against the reciprocal concentration. This provides initial estimates for the parameters

k(rate constant) andK(adsorption constant) [5]. - Independent Adsorption Measurement: The adsorption equilibrium constant

Kobtained from kinetic fitting must be compared with the value measured from an independent adsorption isotherm experiment in the dark. A significant discrepancy invalidates the L-H mechanism for that system [5]. - Mathematical Validation: The quasi-steady-state assumption (QSSA) underlying L-H kinetics can be validated using Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) to confirm a sufficient separation of time scales between adsorption/desorption and the surface reaction [6].

Case Study: L-H Kinetics in Dimethyl Carbonate (DMC) Synthesis

The direct synthesis of Dimethyl Carbonate (DMC) from CO2 and methanol over a CeO2 catalyst is a practical example of L-H mechanism verification.

- Experimental Setup: Reactions are conducted in a batch reactor with a nano-CeO2 catalyst, varying parameters like temperature, catalyst mass, and CO2/MeOH ratio, typically at elevated pressures [8].

- Mechanism Proposal: Based on experimental data, a L-H mechanism is proposed where both CO2 and methanol adsorb onto the catalyst surface before reacting.

- Model Verification: The proposed kinetic model (e.g.,

r = k θ_CO2 θ_MeOH) is fitted to the experimental data. A close alignment between model predictions and experimental results (e.g., a low mean absolute percentage error of 17%) validates the proposed mechanism [8].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key materials and their functions for experiments in this field, drawing from the cited methodologies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimentation | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Catalyst | Provides active surface for adsorption and reaction in L-H mechanism. | CeO2 for DMC synthesis [8]; V2O5 for Hg0 oxidation [5] |

| Homogeneous Catalyst | Molecular metal complex that forms intermediate complexes in solution. | Metal complexes (e.g., Cu, Pd) screened in HTE [7] |

| Fluorogenic Probe | Enables real-time, high-throughput reaction monitoring via optical signals. | Nitronaphthalimide (NN) probe for nitro-reduction [7] |

| Well Plates | Platform for high-throughput, parallel screening of multiple reactions. | 24-well polystyrene plates [7] |

| Spectroscopic Standards | Provides reference for converting fluorescence/absorbance to concentration. | Amine product (AN) in reference well [7] |

| Adsorbate Molecules | Used for independent measurement of adsorption equilibrium constants. | Substrate molecules for dark adsorption tests [5] |

The decision between Langmuir-Hinshelwood heterogeneous catalysts and homogeneous intermediate complex catalysts is not a matter of superiority, but of appropriate application. Heterogeneous L-H systems offer unparalleled advantages in catalyst recovery, stability, and integration into continuous flow reactors, making them ideal for large-scale industrial processes like environmental catalysis and bulk chemical production. Conversely, homogeneous catalysts frequently provide superior activity under milder conditions and exquisite selectivity, which is paramount in the synthesis of complex molecules for the pharmaceutical and fine chemical industries.

The ongoing integration of high-throughput screening and rigorous kinetic modeling, as demonstrated, is crucial for advancing both fields. This comparative guide underscores that the optimal catalytic pathway is determined by the specific economic, environmental, and performance requirements of the intended application.

The precise structure and atomic arrangement of active sites fundamentally determine the performance of both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts. This guide provides an objective comparison between two dominant active site architectures: uniform centers, characterized by consistent, well-defined atomic coordination, and surface atoms, which encompass the diverse sites found on nanoparticle surfaces and solid catalysts. Within the broader thesis of homogeneous versus heterogeneous catalyst performance, this distinction is critical. Homogeneous catalysts often exemplify the ideal of uniform centers, where every molecule possesses identical active sites, while traditional heterogeneous catalysts typically present a distribution of surface sites with varying coordination and reactivity.

The emergence of Single Atom Catalysts (SACs) has blurred this traditional dichotomy, introducing atomically dispersed heterogeneous catalysts with uniform, molecular-like active sites. This comparison will analyze the performance of these site types by examining key metrics such as activity, selectivity, and stability, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies. Understanding these differences is essential for researchers and scientists to rationally design next-generation catalysts for applications ranging from drug development to sustainable energy conversion.

Structural and Chemical Properties Comparison

The intrinsic differences between uniform centers and surface atoms originate from their distinct atomic-scale structures and electronic configurations.

Uniform Active Centers, as exemplified by Single Atom Catalysts (SACs), feature metal atoms individually dispersed on a support material, anchored via coordination to heteroatoms like nitrogen, oxygen, or sulfur [9]. This configuration creates a well-defined, uniform coordination environment for every active site. In homogeneous catalysis, molecular catalysts also present uniform sites, often with precisely designed ligand spheres that create a tailored microenvironment [10]. A key structural advantage of uniform centers is their ability to achieve near-theoretical atom utilization efficiency, as every metal atom can function as an active site [11] [12].

Surface Atoms on nanoparticles or solid catalysts exist in diverse local environments, including terraces, steps, kinks, and defects. This structural heterogeneity leads to a distribution of electronic properties and binding strengths across different surface sites [12]. Traditional supported metal nanoparticles exemplify this architecture, where only a fraction of the total atoms—typically those on the surface with low coordination—participate in catalysis, resulting in lower overall atom efficiency compared to SACs.

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Active Site Types

| Property | Uniform Centers | Surface Atoms |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Structure | Well-defined, isolated atoms | Variety of coordination environments |

| Site Uniformity | High | Low to moderate |

| Atom Utilization | Theoretical maximum (≈100%) | Limited to surface atoms |

| Typical Examples | SACs, Molecular complexes | Metal nanoparticles, Polycrystalline surfaces |

| Coordination Number | Typically low and uniform | Ranges from under-coordinated to fully coordinated |

Tailoring strategies further differentiate these active sites. For uniform centers, techniques like strain engineering, ligand engineering, and axial functionalization can precisely modulate the electronic state of metal centers to optimize intermediate adsorption [9]. For surface architectures, alloying creates diverse atomic neighborhoods. For instance, in a PdCuNi medium entropy alloy, electron-deficient surface Ni atoms were shown to reduce the thermodynamic energy barrier for the formic acid oxidation reaction [13].

Experimental Protocols for Characterization and Analysis

Protocol for X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS)

XAS is a powerful technique for determining the local coordination environment and electronic state of metal centers, especially in uniform catalysts.

- Sample Preparation: Grind the catalyst powder finely and mix uniformly with cellulose or boron nitride. Press the mixture into a thin, uniform pellet suitable for transmission mode measurement. For dilute samples, fluorescence mode may be used.

- Data Collection: Perform experiments at a synchrotron radiation facility. Collect data at the metal edge of interest (e.g., Ru K-edge for Ru SACs) at cryogenic temperatures (e.g., 77 K) to minimize thermal disorder.

- XANES Analysis: Analyze the X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure (XANES) region to determine the average oxidation state of the metal center by comparing the edge position with standard foil references.

- EXAFS Analysis: Process the Extended X-Ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS) region by Fourier transformation. Fit the spectra to determine key structural parameters: coordination numbers, bond distances, and disorder factors for each scattering shell [14].

Protocol for Electrochemical Activity and Stability Measurement

This protocol assesses catalytic performance, particularly for energy-related reactions.

- Electrode Preparation: Disperse 5 mg of catalyst powder in a solution containing 500 µL of ethanol, 450 µL of water, and 50 µL of Nafion solution. Sonicate for 60 minutes to form a homogeneous ink. Pipette a precise volume (e.g., 10 µL) onto a polished glassy carbon electrode and air-dry.

- Electrochemical Testing: Use a standard three-electrode cell with the catalyst-coated electrode as the working electrode. Conduct Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) in an inert electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M KOH) to determine the Electrochemical Surface Area (ECSA) from the double-layer capacitance.

- Activity Measurement: Perform CV or Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV) in an electrolyte containing the reactant (e.g., 0.5 M HCOOH for formic acid oxidation). Report activity normalized by both geometric area and metal mass loading.

- Stability Test: Use Chronoamperometry at a fixed potential or Accelerated Durability Testing (ADT) via repeated potential cycling (e.g., 5000 cycles). Measure the percentage loss of initial activity [13].

Protocol for High-Angle Annular Dark-Field STEM (HAADF-STEM)

HAADF-STEM directly images individual heavy atoms on lighter supports, crucial for confirming single-atom dispersion.

- Sample Preparation: Disperse catalyst powder in ethanol via sonication. Drop-cast a small volume onto a lacey carbon TEM grid and allow to dry.

- Microscope Alignment: Use an aberration-corrected STEM microscope operating at 200 kV. Carefully align the microscope to ensure optimal resolution.

- Imaging: Acquire HAADF-STEM images. The contrast is roughly proportional to the square of the atomic number (Z-contrast). Isolated heavy atoms (e.g., Ru, Pt) appear as bright dots against the darker support [14].

- Analysis: Collect images from multiple regions to confirm the uniform dispersion of single atoms and rule out the presence of nanoparticles.

Experimental Workflow for Active Site Analysis

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

Activity and Selectivity Metrics

Quantitative performance data reveals fundamental trade-offs between the two active site architectures.

Uniform centers, particularly SACs, often demonstrate exceptional selectivity due to the uniformity of their active sites. This minimizes the occurrence of side reactions that typically proceed on different types of surface sites. For instance, Ru single atoms buried in a Ni₃FeN subsurface lattice (Ni₃FeN-Ruburied) exhibited remarkably high selectivity and Faradaic efficiency for the conversion of methanol to formate, attributed to an optimized adsorption configuration for the desired reaction pathway [14]. In homogenous hydrogenation catalysis, bifunctional complexes with uniform active sites achieve high enantioselectivity in the production of fine chemicals [10].

Surface atoms on well-designed nanostructures can achieve extremely high mass activity. The PdCuNi medium entropy alloy aerogel (PdCuNi AA) developed for formic acid oxidation achieved a mass activity of 2.7 A mg⁻¹, surpassing Pd/C by approximately 6.9 times [13]. This high activity stems from synergistic effects between different surface atoms in the alloy, which can break scaling relations that limit simpler catalysts.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Representative Catalysts

| Catalyst | Reaction | Key Performance Metric | Active Site Architecture |

|---|---|---|---|

Ni₃FeN-Ruburied [14] |

Methanol Oxidation | High Faradaic efficiency for formate | Uniform Center (Buried Single Atom) |

| PdCuNi AA [13] | Formic Acid Oxidation | Mass activity: 2.7 A mg⁻¹ | Surface Atoms (Medium Entropy Alloy) |

| Mn-based pre-catalyst [10] | Carbonyl Hydrogenation | High enantioselectivity | Uniform Center (Homogeneous Molecular Complex) |

| Pt1/FeOx [11] | CO Oxidation | High intrinsic activity & 100% atom utilization | Uniform Center (SAC) |

Stability and Deactivation Mechanisms

The stability profiles and deactivation pathways differ significantly between the two site types.

- Uniform Centers: The primary deactivation mechanism is the migration and agglomeration of isolated metal atoms into nanoparticles, driven by their high surface energy [9] [11]. A critical factor for stability is the strength of the metal-support interaction. Strong covalent bonding can significantly anchor single atoms and prevent their migration. For homogeneous molecular catalysts, decomposition or ligand loss under harsh conditions are common failure modes [10].

- Surface Atoms: The main deactivation mechanisms include particle sintering (a form of agglomeration), poisoning by strong-adsorbing species (e.g., CO on Pd), and surface reconstruction [13] [14]. Alloying can improve stability; the PdCuNi alloy showed enhanced resistance to CO poisoning due to electronic structure modification of surface Pd atoms [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research into active sites relies on specialized materials and reagents.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Metal Precursors (e.g., Metal acetylacetonates, chlorides) | Source of active metal for catalyst synthesis. |

| Support Materials (e.g., MOFs, g-C₃N₄, Graphene, Carbon nanotubes) | High-surface-area matrices to anchor and stabilize active sites. |

| Structure-Directing Agents (e.g., PS-b-PEO, surfactants) | Control morphology and porosity during synthesis. |

| NaBH₄ | Common reducing agent for synthesizing metal nanoparticles and alloys. |

| Heteroatom Dopants (e.g., N, S, P precursors) | Create anchoring sites on supports for single metal atoms. |

| Probe Molecules (e.g., CO, H₂) | Used in chemisorption studies to quantify and characterize active sites. |

Integrated Discussion: Strategic Choice of Active Sites

The choice between uniform centers and surface atoms is not about superiority, but rather about strategic application based on the desired catalytic outcome.

Decision Logic for Active Site Selection

Uniform centers are optimal when the priority is high selectivity and atom efficiency. Their well-defined structure allows for precise mechanistic studies and rational optimization via ligand or coordination engineering [9] [10]. This makes them ideal for complex transformations in pharmaceutical synthesis or for reactions where specific product formation is critical. The primary challenge remains stabilizing these sites against agglomeration, particularly at high loadings required for industrial application [9].

Surface atom architectures are advantageous for achieving high mass activity and breaking scaling relations. The synergistic interplay between different elements in an alloy can create unique active sites that are not possible in uniform centers, leading to exceptional activity for reactions like formic acid oxidation [13]. The main challenges involve managing site heterogeneity and preventing deactivation via poisoning or sintering.

Emerging strategies seek to combine the advantages of both paradigms. For example, the concept of burying single atoms in subsurface lattices, as demonstrated with Ni₃FeN-Ruburied, aims to utilize uniform centers to electronically modify surrounding surface atoms [14]. This creates optimized surface active sites that are more stable and selective, representing a promising direction for next-generation catalyst design that transcends the traditional homogeneous-heterogeneous divide.

In heterogeneous catalysis, where catalysts and reactants exist in different phases, the process of adsorption is the indispensable first step that initiates all subsequent chemical transformations [1] [15]. Unlike absorption, where substances penetrate the bulk of a material, adsorption specifically refers to the adhesion of atoms, ions, or molecules (collectively known as adsorbates) to the surface of a solid or liquid catalyst (the adsorbent) [16] [17]. This surface-based phenomenon enables the critical interactions between reactant molecules and catalytic active sites, ultimately lowering activation energies and accelerating reaction rates without the catalyst itself being consumed [1].

The distinction between adsorption and absorption is fundamental, as summarized in Table 1. While absorption involves the uptake and distribution of a substance throughout the volume of another material (as seen when a sponge soaks up water), adsorption is exclusively a surface process where molecules accumulate at the interface without penetrating the bulk structure [16] [17] [18]. This surface confinement is what makes adsorption particularly powerful in catalytic applications, as it creates localized regions of high reactant concentration and facilitates specific molecular orientations that favor desired reaction pathways.

Table 1: Fundamental Distinction Between Adsorption and Absorption

| Parameter | Adsorption | Absorption |

|---|---|---|

| Process Nature | Surface phenomenon | Bulk phenomenon |

| Penetration Depth | Molecules adhere to the surface without penetration | Molecules penetrate and distribute throughout the material's volume |

| Rate of Reaction | Typically fast initially, then equilibrates | May be slower, dependent on diffusion |

| Temperature Effect | Generally decreases with increasing temperature | May increase with temperature due to enhanced diffusion |

| Heat Exchange | Exothermic process | Can be endothermic or exothermic |

| Reversibility | Often reversible, especially physisorption | Frequently irreversible |

| Examples | Activated carbon trapping toxins; oxygen on alveolar surfaces | Sponge soaking up water; nutrient uptake in intestines |

Within heterogeneous catalytic systems, adsorption manifests through two primary mechanisms with distinct characteristics and implications for catalyst performance: physisorption (physical adsorption) and chemisorption (chemical adsorption) [16]. Understanding the interplay between these mechanisms is crucial for designing advanced catalytic materials and optimizing reaction conditions for applications ranging from industrial chemical production to pharmaceutical synthesis and environmental remediation [1] [15].

Physisorption and Chemisorption: Fundamental Mechanisms and Energetics

Physisorption: Surface Adhesion Through Weak Intermolecular Forces

Physisorption is characterized by the adherence of adsorbate molecules to a catalyst surface through weak van der Waals forces or other physical interactions, without the formation of chemical bonds [16] [15]. This process is reversible and typically occurs at relatively low temperatures [17]. The adsorption enthalpy for physisorption is generally low, ranging from -20 to -40 kJ/mol, comparable to the heat of condensation [16]. Due to its non-specific nature, physisorption often results in multilayer formation and is not highly selective to particular molecular species [15].

In catalytic systems, physisorption serves as a crucial preliminary step that concentrates reactant molecules near active sites, increasing the probability of subsequent chemisorption and reaction [15]. The weak, non-directional nature of the interaction means physisorbed molecules retain their electronic structure and can readily diffuse across the catalyst surface, sampling various potential adsorption configurations before transitioning to more stable chemisorbed states or desorbing back into the fluid phase [15].

Chemisorption: Chemical Bond Formation and Surface Reactivity

Chemisorption involves the formation of chemical bonds between adsorbate molecules and specific sites on the catalyst surface [16]. This process is characterized by significantly stronger interactions, with adsorption enthalpies typically ranging from -40 to -800 kJ/mol, comparable to chemical bond energies [16]. Unlike physisorption, chemisorption is highly specific, often irreversible, and typically limited to a monolayer due to the saturation of available surface bonding sites [17].

The strong electronic interactions in chemisorption frequently lead to significant distortion of the adsorbate's molecular structure, activation of chemical bonds, and formation of new reaction intermediates [15]. For example, in CO₂ hydrogenation reactions on metal surfaces, chemisorption can result in the bending of the normally linear CO₂ molecule, facilitating subsequent bond-breaking and transformation into products like methanol [15]. The specificity of chemisorption arises from the requirement for precise geometric and electronic compatibility between the adsorbate and the surface active sites, making it a highly selective process that directly determines catalytic activity and reaction pathway selectivity [1] [19].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Physisorption and Chemisorption in Catalytic Systems

| Characteristic | Physisorption | Chemisorption |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Forces | Weak van der Waals forces | Strong chemical bonds |

| Adsorption Enthalpy | -20 to -40 kJ/mol (exothermic) | -40 to -800 kJ/mol (exothermic) |

| Specificity | Non-specific | Highly specific to surface sites |

| Temperature Range | Lower temperatures, decreases with heating | Higher temperatures, may increase initially then decrease |

| Surface Coverage | Multilayer possible | Monolayer only |

| Reversibility | Highly reversible | Often irreversible or slowly reversible |

| Activation Energy | Low or none | Significant activation energy possible |

| Role in Catalysis | reactant concentration, precursor to chemisorption | Bond activation, intermediate formation |

| Electronic Structure | Minimal perturbation of adsorbate orbitals | Significant orbital rearrangement, possible charge transfer |

The Adsorption Process: From Physisorption to Catalytic Transformation

The relationship between physisorption and chemisorption in functional catalytic systems is often sequential and complementary, as visualized in Figure 1. The process typically begins with the physisorption of reactant molecules from the bulk fluid phase onto the catalyst surface, followed by surface diffusion to active sites where chemisorption can occur [15]. The chemically activated species then undergoes transformation through various surface reactions before the products desorb, regenerating the active sites for subsequent catalytic cycles [1].

Figure 1: Sequential process of adsorption and reaction in heterogeneous catalytic systems, showing the transition from physisorption to chemisorption and eventual product formation.

The dynamic equilibrium between physisorbed and chemisorbed states is influenced by reaction conditions including temperature, pressure, and the chemical potential of reactants [15]. Higher temperatures generally favor chemisorption due to the activation energy requirement for bond formation, while extremely high temperatures may promote desorption of both physisorbed and chemisorbed species [17]. Pressure increases typically enhance surface coverage for both physisorption and chemisorption, though the effects are more pronounced for physisorption at lower temperatures [17] [15].

Characterization and Experimental Methodologies for Adsorption Analysis

Experimental Protocols for Differentiating Physisorption and Chemisorption

Researchers employ multiple experimental techniques to characterize adsorption mechanisms and quantify their parameters. Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD) is a widely used method that involves adsorbing a gas onto a catalyst surface at low temperature, then gradually heating while monitoring desorbed species [19]. Physisorbed molecules typically desorb at lower temperatures (often below 150 K), while chemisorbed species require higher temperatures (300-1000 K) corresponding to their stronger binding energies [19].

Adsorption Isotherm Measurements provide information about surface area, pore size distribution, and adsorption capacity [16]. Physisorption isotherms typically exhibit reversible Type II or IV characteristics with hysteresis loops associated with capillary condensation in mesopores, while chemisorption often shows Langmuir-type (Type I) behavior indicative of monolayer formation [16]. Microcalorimetry directly measures heats of adsorption, with physisorption displaying relatively constant, low heats versus chemisorption which shows higher, often coverage-dependent heats due to surface heterogeneity and adsorbate-adsorbate interactions [15].

Spectroscopic techniques including Infrared Spectroscopy (IR), X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), and Solid-State NMR provide molecular-level insights into adsorption mechanisms [19]. IR spectroscopy can detect perturbations in molecular vibrations upon adsorption, with chemisorption typically causing larger frequency shifts and sometimes the appearance of new vibrational modes corresponding to surface chemical bonds [19]. XPS reveals changes in electronic structure, including oxidation state changes and charge transfer processes characteristic of chemisorption [19].

Computational Approaches for Modeling Adsorption Processes

Computational methods have become indispensable for understanding adsorption phenomena at the atomic level. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations are widely employed to predict adsorption energies, optimal adsorption configurations, and electronic structure changes upon adsorption [20] [15] [19]. Standard DFT protocols involve building surface slab models, sampling different adsorption sites, and calculating adsorption energies using the formula:

[E{\text{ad}} = E{\text{adsorbate}} - E_{\text{}} - E_{\text{adsorbate}}]

where (E{\text{*adsorbate}}) is the energy of the surface with adsorbed species, (E{\text{*}}) is the energy of the clean surface, and (E_{\text{adsorbate}}) is the energy of the isolated adsorbate molecule [15].

More advanced multiscale modeling approaches integrate Kohn-Sham DFT with classical DFT to account for both bond formation and non-bonded interactions in realistic reaction environments [15]. This is particularly important for industrial conditions where high temperatures and pressures create inhomogeneous gas distributions near catalyst surfaces, with local concentrations potentially hundreds of times higher than in the bulk phase [15]. Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations further incorporate temperature effects and allow sampling of various adsorption configurations and their transitions [15].

Recent advances include automated frameworks like autoSKZCAM that leverage correlated wavefunction theory for more accurate prediction of adsorption enthalpies, achieving close agreement with experimental values across diverse adsorbate-surface systems [19]. Machine learning approaches, particularly generative models, are emerging as powerful tools for efficiently sampling adsorption geometries and predicting stable configurations without exhaustive DFT calculations [20].

Table 3: Experimental and Computational Methods for Adsorption Analysis

| Methodology | Key Measured Parameters | Applications in Adsorption Studies | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD) | Desorption temperatures, binding energies, surface coverage | Distinguishing physisorption vs. chemisorption; active site quantification | May alter surface during heating; complex spectra for mixed adsorption |

| Adsorption Microcalorimetry | Heat of adsorption, site energy distribution | Measuring strength of surface-adsorbate interactions; surface heterogeneity | Requires careful temperature control; interpretation challenges for complex surfaces |

| Infrared Spectroscopy (IR) | Vibrational frequency shifts, new bond formation | Identifying adsorption configurations; molecular-level bonding information | Surface selection rules; limited to IR-active modes; high reflectivity needs |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Elemental composition, oxidation states, charge transfer | Electronic structure changes during chemisorption; oxidation state determination | Ultra-high vacuum required; surface-sensitive but not exclusively surface-specific |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Adsorption energies, optimized geometries, electronic structure | Predicting stable configurations; reaction pathways; electronic origins of bonding | Functional-dependent accuracy; dispersion corrections needed for physisorption |

| Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD) | Finite-temperature behavior, adsorption/desorption dynamics | Realistic reaction conditions; entropic effects; rare events | Computationally expensive; limited timescales |

| Machine Learning/Generative Models | Efficient configuration sampling, property-structure relationships | High-throughput screening; discovery of novel adsorption sites | Training data requirements; transferability to new systems |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for Adsorption Studies

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Adsorption and Catalytic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Adsorption Studies | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Activated Carbon | High-surface-area adsorbent with tunable porosity | Physisorption studies; reference material for surface area measurements; contaminant removal |

| Silica Gel | Polar adsorbent with surface hydroxyl groups | Water vapor adsorption studies; chromatographic separation; catalyst support |

| Zeolites | Crystalline microporous aluminosilicates | Shape-selective adsorption and catalysis; acid-base catalysis studies; molecular sieves |

| Metal Nanoparticles (Pt, Pd, Cu, etc.) | Active sites for chemisorption and catalytic transformations | Hydrogenation/dehydrogenation reactions; oxidation catalysis; model catalysts |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Highly porous, tunable coordination polymers | Gas storage studies; selective adsorption; catalyst supports with confined environments |

| Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) | Isolated metal atoms on supports | Maximizing atom efficiency; fundamental studies of active sites; selective transformations |

| Magnetic Nanocatalysts | Magnetically recoverable catalyst platforms | Sustainable catalysis; easy separation studies; recyclability testing |

Adsorption in Heterogeneous vs. Homogeneous Catalyst Systems

The fundamental distinction between heterogeneous and homogeneous catalytic systems lies in the phase relationship between catalyst and reactants, which profoundly influences adsorption phenomena and overall catalytic performance [1] [21]. In heterogeneous catalysis, adsorption occurs at solid-fluid interfaces, creating unique challenges and opportunities not present in homogeneous systems where catalyst and reactants coexist in the same phase [1].

Homogeneous catalysts typically involve molecular-scale active sites that interact with reactants through well-defined coordination chemistry, often resulting in high selectivity and reproducible active sites [22] [21]. However, these systems face significant challenges in catalyst separation and recycling, with industrial applications often requiring complex processes to recover expensive catalytic species [22] [21]. In contrast, heterogeneous systems facilitate easy catalyst separation through simple filtration or centrifugation, though increasingly sophisticated magnetic nanocatalysts now enable even more efficient magnetic recovery [21].

The adsorption characteristics differ substantially between these systems. Heterogeneous catalysts exhibit a distribution of adsorption sites with varying energies and geometries, including terraces, steps, kinks, and defects [1]. This heterogeneity can lead to multiple reaction pathways and sometimes lower selectivity compared to homogeneous analogues [1]. However, it also creates opportunities for optimizing catalyst performance through surface engineering and nanostructuring [19].

Table 5: Performance Comparison of Homogeneous, Conventional Heterogeneous, and Advanced Heterogeneous Catalytic Systems

| Performance Metric | Homogeneous Catalysts | Conventional Heterogeneous Catalysts | Advanced Heterogeneous (Magnetic, SACs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Site Accessibility | High (molecular dispersion) | Limited (surface confinement) | Moderate to High (nanostructured) |

| Mass Transfer Limitations | Minimal | Significant intraporous diffusion | Reduced (nanoscale dimensions) |

| Selectivity | Typically high | Variable, often lower | Can approach homogeneous levels |

| Catalyst Recovery | Difficult, often incomplete | Easy (filtration, centrifugation) | Very easy (magnetic separation) |

| Reusability | Limited | Good to excellent | Excellent |

| Active Site Characterization | Straightforward (spectroscopy) | Challenging (surface heterogeneity) | Improving with single-site systems |

| Reaction Rate | Generally fast | Often limited by mass transfer | Enhanced through nanoscale effects |

| Applications | Fine chemicals, pharmaceuticals | Bulk chemicals, environmental catalysis | Bridging both sectors |

Recent advances in heterogeneous catalyst design aim to combine the advantages of both approaches. Single-atom catalysts (SACs) feature isolated metal atoms on solid supports, creating well-defined active sites that bridge homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis [1]. Hybrid catalysts incorporate molecular catalytic species within porous solid matrices, such as the "click-heterogenization" approach that immobilizes phosphine ligands in metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) while maintaining their mobility and catalytic precision [22]. Magnetic nanocatalysts represent another innovative approach, combining easy magnetic separation with high surface area and tunable functionality [21].

The adsorption characteristics in these advanced systems often differ from conventional heterogeneous catalysts. In MOF-based hybrid catalysts, the confined pore environment creates unique adsorption landscapes that can enhance selectivity [22]. In magnetic nanocatalysts, the functionalized surfaces provide tailored adsorption sites while maintaining the practical advantage of facile magnetic recovery [21]. These developments illustrate how understanding and controlling adsorption processes enables the design of catalytic systems that transcend traditional boundaries between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis.

The critical role of adsorption in heterogeneous catalytic systems extends from fundamental molecular interactions to practical applications in chemical production, environmental protection, and energy sustainability. The distinction between physisorption and chemisorption remains foundational for understanding catalyst behavior, with physisorption serving to concentrate reactants near surfaces while chemisorption activates chemical bonds for transformation [16] [15]. The complementary nature of these processes enables the remarkable efficiency and specificity of modern heterogeneous catalysts.

Future advancements in adsorption and catalysis research will likely focus on several key areas. Multiscale modeling approaches that bridge quantum mechanical calculations of bond formation with classical treatments of molecular environments will provide more accurate predictions of catalyst performance under industrially relevant conditions [15]. Machine learning and generative models are emerging as powerful tools for exploring the vast configuration space of surface-adsorbate complexes and identifying novel catalytic materials [20]. Advanced characterization techniques with higher spatial and temporal resolution will reveal dynamic adsorption processes and transient intermediates previously inaccessible to experimental observation [19].

The ongoing convergence of homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis through single-atom catalysts, hybrid materials, and sophisticated nanostructuring promises to overcome traditional limitations while preserving the advantages of each approach [1] [22] [21]. As these developments progress, the fundamental principles of adsorption—the critical initial step in all heterogeneous catalytic processes—will continue to guide the design of more efficient, selective, and sustainable chemical technologies.

Real-World Applications and Performance Metrics in Industry and Research

The pursuit of high-selectivity catalysis represents a cornerstone of modern active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) synthesis, enabling the precise molecular transformations required for complex drug molecules. Catalysts serve as the silent orchestrators of API manufacturing, accelerating reactions while remaining unconsumed and fundamentally transforming sluggish chemical processes into rapid, high-yield syntheses [23]. Within pharmaceutical manufacturing, the choice between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalytic systems presents a significant strategic dilemma, with each approach offering distinct advantages and limitations in selectivity, efficiency, and practicality [23].

Homogeneous catalysts, which exist in the same phase (typically liquid) as the reactants, provide unparalleled selectivity and efficiency under mild conditions, making them indispensable for constructing complex molecular architectures found in pharmaceuticals [24]. Their heterogeneous counterparts, being in a different phase (typically solid) from the reactants, offer advantages in recoverability and continuous processing but often with compromised selectivity [24]. This comprehensive guide objectively compares the performance of these catalytic systems, providing experimental data and methodologies to inform selection for specific API synthesis applications.

Fundamental Principles: Homogeneous versus Heterogeneous Catalysis

Defining Characteristics and Mechanisms

The fundamental distinction between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts lies in their phase relationship with reactants. Homogeneous catalysts are molecularly dispersed in the same phase (usually liquid) as the reaction mixture, allowing for uniform distribution and intimate contact at the molecular level [24]. This phase homogeneity enables precise interaction with reactant molecules, often leading to superior selectivity and specificity for targeted transformations. In contrast, heterogeneous catalysts exist in a different phase (typically solid) from the reactants, with reactions occurring exclusively at the catalyst surface where active sites facilitate molecular transformations [24].

The mechanistic pathways differ significantly between these systems. Homogeneous catalysis involves molecular-level interactions in solution, where the catalyst forms defined intermediates with reactants throughout the reaction medium [24]. Heterogeneous catalysis follows surface-mediated mechanisms where reactants must adsorb onto active sites, undergo transformation, and then desorb as products [24]. This fundamental difference in mechanism profoundly influences their applications, advantages, and limitations in API synthesis.

Comparative Advantages and Limitations

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalytic Systems

| Aspect | Homogeneous Catalysts | Heterogeneous Catalysts |

|---|---|---|

| Phase Relationship | Same as reactants (usually liquid) [24] | Different from reactants (typically solid) [24] |

| Reaction Mode | Occurs uniformly throughout the solution [24] | Occurs on the surface of the catalyst [24] |

| Selectivity | Higher selectivity towards specific reactions [24] | Lower selectivity; broader range of reactions [24] |

| Separation & Recovery | Challenging to separate from products [24] | Facile separation post-reaction [24] |

| Active Sites | Molecular level interactions in solution [24] | Surface active sites with potential diffusional limitations [23] |

| Reaction Conditions | Milder conditions (lower temperatures/pressures) [23] | Often require more extreme conditions |

| Catalyst Optimization | Tunable via ligand design [23] | Optimized through surface engineering and support materials [25] |

| Sensitivity to Poisoning | Generally more susceptible to poisons | Surface can be poisoned or blocked by impurities [24] |

Experimental Data and Performance Metrics in API Synthesis

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Rigorous experimental studies provide critical performance data for informed catalyst selection in pharmaceutical applications. The quantitative differences between homogeneous and heterogeneous systems manifest in yield, selectivity, and operational efficiency metrics essential for API manufacturing.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics in API Synthesis Applications

| Application/Reaction | Catalyst System | Key Performance Metrics | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrolysis of Cellulose | Ni2Fe3 (Homogeneous) [26] | Bio-oil yield: 46.7% ± 0.5% [26] | 3 g catalyst mixed with 6 g cellulose, fixed bed reactor, <450°C [26] |

| Pyrolysis of Cellulose | ZSM-5 (Homogeneous) [26] | Bio-oil yield: 31.2% ± 0.6% [26] | 3 g catalyst mixed with 6 g cellulose, fixed bed reactor, <450°C [26] |

| Pyrolysis of Cellulose | No catalyst [26] | Bio-oil yield: 39.2% ± 1.0% [26] | 6 g cellulose alone, fixed bed reactor, <450°C [26] |

| C-H Activation Reactions | Heterogeneous Pd catalyst [27] | Pd contamination: <250 ppb after filtration [27] | Heterogeneous Pd in C-H activation, filtration separation |

| C-H Activation Reactions | Homogeneous Pd catalyst [28] | Significant Pd contamination requiring complex purification [28] | Traditional homogeneous Pd catalysis in solution |

| Catalyst Recycling | Heterogeneous Pd catalyst [27] | Recycled >16 times with maintained activity [27] | Filtration recovery and reuse in multiple cycles |

| Asymmetric Hydrogenation | Iridium complexes (Homogeneous) [23] | High enantioselectivity for β-blocker synthesis [23] | Homogeneous iridium catalysts under mild conditions |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Homogeneous Catalytic Pyrolysis for Bio-oil Production

This representative protocol demonstrates the experimental approach for evaluating homogeneous catalyst performance in biomass conversion, with relevance to pharmaceutical precursor synthesis [26]:

Catalyst Preparation:

- Ni2Fe3 cluster catalysts are synthesized via sol-gel method confirmed by XRD analysis showing crystalline structure with broad diffraction peaks indicating small crystallite size [26]

- Catalyst composition verified by SEM imaging showing uneven powdered structure with EDS confirming elemental composition [26]

Experimental Setup:

- Reactor System: Fixed-bed reactor operated at temperatures below 723.15K (450°C) [26]

- Feedstock Preparation: 6g cellulose (biomass model compound) thoroughly mixed with 3g catalyst [26]

- Atmosphere: Inert conditions maintained throughout pyrolysis [26]

Analysis Methods:

- Product Yield Quantification: Bio-oil, gas, and char/coke masses measured gravimetrically [26]

- Bio-oil Quality Assessment: Sugar concentration reduction measured via chromatographic methods [26]

- Catalyst Recyclability: Recovery and repeated use for multiple cycles with performance monitoring [26]

Protocol: Heterogeneous Palladium Catalysis for C-H Activation

This protocol outlines methodology for evaluating heterogeneous catalyst systems in pharmaceutically relevant C-H functionalization [27]:

Catalyst System:

- Supported heterogeneous palladium catalysts designed for C-H activation reactions [27]

- Capable of mediating multiple transformations: C-O, C-Cl/Br/I, C-C, C-N, C-F and C-CF3 bonds [27]

Performance Metrics:

- Residual Metal Contamination: ICP-MS analysis of palladium content in final products [27]

- Catalyst Longevity: Multiple reaction cycles (≥16) with consistent turnover frequency [27]

- Reaction Kinetics: Turnover frequency measurements demonstrating improved reaction rates [27]

Separation Protocol:

- Simple filtration separation achieving palladium contamination levels below 250 ppb [27]

- Direct catalyst reuse without complex regeneration protocols [27]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Catalytic API Synthesis Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Platinoid Catalysts (Pd, Ru, Rh) [28] | Cross-coupling reactions for C-C and C-N bond formation [28] | Suzuki-Miyaura, Negishi, and Buchwald-Hartwig reactions [28] |

| Ligand Systems (TMLs, Phosphines) [25] [23] | Modulate electronic environment and steric properties of metal centers [23] | Trost modular ligands for asymmetric allylic alkylation [25] |

| Organocatalysts (Proline derivatives) [23] | Metal-free asymmetric synthesis avoiding toxicity concerns [23] | Chiral API synthesis with high enantiomeric excess [23] |

| Enzyme Biocatalysts (Engineered transaminases) [23] | Biocatalytic transformations with high stereoselectivity [23] | Conversion of ketones to chiral amines for antidepressants [23] |

| Zeolite Catalysts (ZSM-5, TS-1) [25] [23] | Heterogeneous catalysts with defined pore structures [25] | Continuous hydroxylation processes for steroid APIs [23] |

| Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) [23] | Maximized atom efficiency with isolated metal atoms on supports [23] | Platinum on carbon nitride for nitro compound reduction [23] |

| Flow Reactor Systems [2] [29] | Continuous processing with improved heat/mass transfer [2] | API synthesis under photoredox or electrochemical conditions [2] |

Technological Innovations and Emerging Methodologies

Advanced Catalyst Design Strategies

Modern catalyst development employs sophisticated computational and engineering approaches to enhance performance:

Computational Design Tools:

- Density Functional Theory (DFT) simulations predict electron configurations and catalytic activity, enabling rational catalyst design before experimental validation [23]

- Machine learning models reduce computational costs for reaction thermochemistry calculations, enabling efficient catalyst screening [23]

- Generative adversarial networks (GANs) propose novel metal-ligand combinations for testing via automated high-throughput screening [23]

Nanostructured Catalyst Engineering:

- Composition regulation, size optimization, morphology control, and structural engineering to enhance reactivity [23]

- Mesoporous materials with tailored pore sizes selectively admit specific substrates while preventing catalyst deactivation [23]

- Gold nanoparticles catalyze oxidation reactions under mild conditions, preserving heat-sensitive pharmaceutical intermediates [23]

Ligand Engineering Innovations:

- Custom-designed ligands modulate electronic environment of metal centers to steer reaction selectivity [23]

- Redox-active ligands enable earth-abundant metal catalysis (e.g., iron-catalyzed C-H activation) as cost-effective alternatives to precious metals [23]

Integrated Process Technologies

The integration of catalysis with advanced processing technologies represents a frontier in pharmaceutical manufacturing:

Continuous Flow Systems:

- Microreactors with immobilized catalysts enhance mixing and heat transfer, expediting reactions like nitration for cardiovascular drugs [23]

- Homogeneous catalysts in continuous flow enable safer handling of sensitive or toxic reagents [29]

- PAT (Process Analytical Technology) tools enable real-time monitoring and control of critical parameters and product quality [2]

Hybrid Catalytic Systems:

- Biphasic systems where catalysts dissolve in ionic liquids separate from organic solvents, reducing leaching and simplifying recovery [23]

- "Smart" catalysts with switchable phase behavior using CO2/N2 or temperature triggers for facile separation [25]

- Merged catalytic approaches combining homogeneous, heterogeneous, and biocatalytic methods in one-pot systems [25]

Catalytic Mechanisms and Workflow Visualization

Homogeneous Palladium Catalytic Cycle for C-C Bond Formation

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanism of homogeneous palladium catalysis in cross-coupling reactions, a cornerstone methodology for C-C bond formation in API synthesis [28]:

Integrated Workflow for Catalyst Screening and Optimization

This workflow diagram outlines a modern approach to catalyst development and optimization, integrating computational and experimental methods:

The selection between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalytic systems for API synthesis requires careful consideration of multiple performance factors. Homogeneous catalysts offer superior selectivity and efficiency for complex molecular transformations, particularly in stereoselective synthesis, but present significant challenges in separation and metal contamination [24] [28]. Heterogeneous systems provide practical advantages in continuous processing, catalyst recovery, and reduced metal contamination, though often with compromised selectivity [24] [27].

Emerging technologies including flow chemistry, immobilized catalysts, computational design, and hybrid approaches are progressively blurring the historical boundaries between these systems [2] [23] [29]. The optimal catalytic strategy depends fundamentally on the specific synthetic transformation, product quality requirements, and manufacturing constraints, with neither approach representing a universal solution for all pharmaceutical synthesis challenges. As catalytic technologies continue to evolve, the integration of both homogeneous and heterogeneous approaches within unified synthetic strategies will likely define the future of efficient and sustainable API manufacturing.

Catalytic processes constitute the backbone of modern chemical and biochemical technologies, distinguished by three principal features: (i) acceleration of chemical reaction rates, (ii) invariance of the thermodynamic equilibrium composition at a given temperature and pressure, and (iii) the catalyst is not consumed during the reaction [1]. The fundamental mechanistic basis for catalytic action is the lowering of the activation energy barrier through specific interactions between reactants and catalytic centers [1]. In industrial contexts, the choice between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis involves complex trade-offs. For gas-phase reactions such as ammonia synthesis, SO₂ oxidation, and oxidation of naphthalene to phthalic anhydride, heterogeneous catalysis is typically preferred due to easier separation of catalysts from products and compatibility with continuous flow reactors [1]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of catalyst performance within the broader thesis of homogeneous versus heterogeneous catalyst research, with particular emphasis on ammonia synthesis as a paradigmatic bulk chemical process.

Theoretical Framework: Homogeneous vs. Heterogeneous Catalysis

Fundamental Distinctions and Applications

Catalytic systems are generally classified into three major categories [1]. Homogeneous catalysts exist in the same phase (typically liquid) as the reactants, often exhibiting high selectivity and uniform active sites but requiring complex separation processes. Heterogeneous catalysts exist in a different phase (typically solid) from the reactants (gaseous or liquid), offering easier separation, reusability, and thermal stability but potentially presenting mass transfer limitations. Biocatalysis utilizes enzymes or whole microorganisms, typically in the liquid phase, offering exceptional selectivity under mild conditions but with sensitivity to operational parameters.

The selection between homogeneous and heterogeneous systems involves critical trade-offs. Heterogeneous systems often suffer from limitations in mass and heat transport, which can lead to local hot spots, rapid deactivation, and reduced selectivity [1]. However, they remain indispensable for gas-phase reactions in bulk chemical processing like ammonia synthesis [1].

Comparative Advantages and Limitations

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison Between Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalysis

| Parameter | Homogeneous Catalysis | Heterogeneous Catalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Phase | Catalyst and reactants in same phase (typically liquid) | Catalyst and reactants in different phases (typically solid-gas) |

| Active Sites | Uniform, well-defined | Non-uniform, varied (edges, corners, steps, vacancies) |

| Separation | Complex (distillation, extraction) | Simple (filtration, decantation) |

| Thermal Stability | Generally limited | High temperature tolerance |

| Selectivity | Typically high | Variable |

| Application in Ammonia Synthesis | Not commercially used | Industrial standard (Fe-, Ru-based catalysts) |

| Mass/Heat Transfer | Generally efficient | Potential limitations leading to hot spots |

Case Study: Ammonia Synthesis via Heterogeneous Catalysis

Conventional Catalysts and Mechanisms

The Haber-Bosch process for ammonia synthesis from nitrogen and hydrogen predominantly employs Fe-based catalysts under high pressures (15–30 MPa) and temperatures (400°C–500°C), accounting for approximately 1% of global energy consumption [30]. The process relies on the ability of transition metal catalysts to activate the extremely stable N≡N bond (945 kJ/mol) [30]. Ruthenium (Ru) based catalysts offer higher activity than traditional iron catalysts but at higher cost [30]. Promoters such as alkali metals (e.g., K, Cs), alkaline earth metals (e.g., Ba, Ca), and rare earth metals (e.g., La) are crucial for enhancing catalytic performance by modifying the electronic structure of active sites and improving dissociation rates [30].

Emerging Catalyst Technologies

Recent research has focused on developing novel catalyst systems that operate under milder conditions. Spin promotion mechanisms have been discovered that can activate originally unreactive magnetic materials like Cobalt (Co) by hetero metal atoms for ammonia synthesis [30]. This spin-mediated promotion effect is related to the ability to quench the Co or Ni spin moment in the vicinity of promoter atoms adsorbed at active step sites [30]. The transition state for N₂ dissociation (the rate-determining step on Co catalysts) is substantially stabilized as the spin moment decreases induced by metal promoters, thus increasing overall reactivity [30].

The Co/NbN interphase represents an effective ammonia synthesis catalyst system that extends the validation of spin effects to nitride promoters beyond their metallic counterparts [30]. This system demonstrates how spin-mediated promotion mechanisms can guide the design of more active and diverse catalysts beyond traditional Fe and Ru systems [30].

Experimental Comparison of Catalyst Performance

Catalyst Evaluation Methodologies for Renewable Energy Applications

Conventional catalyst evaluation methods assume constant feedstock supply, but with hydrogen production from renewable-powered electrolysis having fluctuating supply, new evaluation paradigms are needed [31]. A comprehensive methodology employs three complementary evaluation approaches [31]:

Light-off Performance: Determines the temperature at which the catalyst becomes active, crucial for frequent start-up/shutdown operations with renewable feedstocks. The "light-off value" is the reciprocal temperature at which 50 ppm of ammonia is produced, obtained by linear regression extrapolation [31].

Equilibrium Achievement Degree: Measures how closely the catalyst approaches thermodynamic equilibrium concentrations across temperatures, indicating the balance between ammonia formation and decomposition reactions [31].

Maximum Ammonia Concentration: Determines the peak catalytic activity under optimal conditions, representing the traditional evaluation metric [31].

These three metrics can be integrated into a three-axis graph for intuitive catalyst screening, providing a rapid assessment method suitable for renewable energy applications with fluctuating feedstocks [31].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data for Ammonia Synthesis Catalysts

| Catalyst System | Light-Off Value (1000/K) | Equilibrium Achievement Degree (%) | Maximum NH₃ Concentration (volppm) | Optimal Temperature Range (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Fe-based | 1.45 | 65-75 | 15,000-18,000 | 450-500 |

| Ru/MgO | 1.52 | 70-80 | 18,000-21,000 | 400-450 |