Improving Stereoselectivity in Asymmetric Synthesis: Strategies for Drug Development

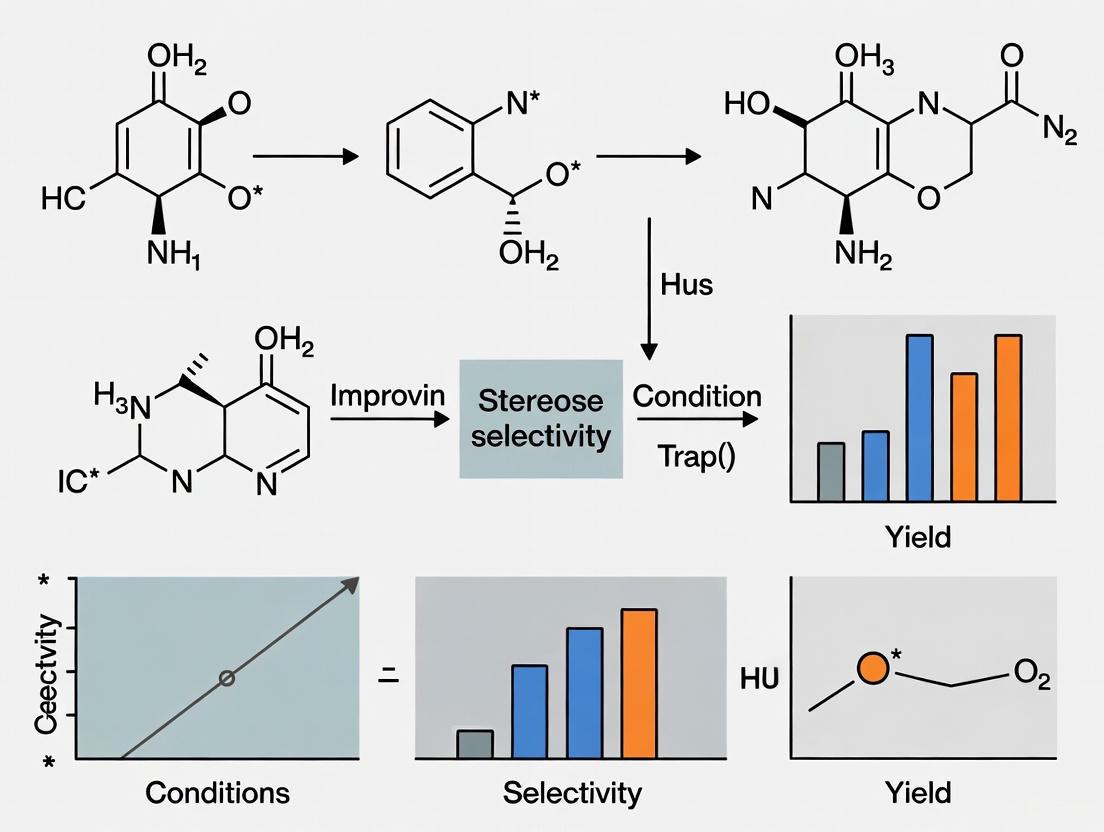

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on advancing stereoselectivity in asymmetric synthesis.

Improving Stereoselectivity in Asymmetric Synthesis: Strategies for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on advancing stereoselectivity in asymmetric synthesis. It covers the fundamental principles of stereoselectivity and its critical impact on drug efficacy and safety. The content explores state-of-the-art methodological approaches, including chiral auxiliaries and catalytic asymmetric synthesis, alongside practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Furthermore, it details analytical techniques for validating stereochemical outcomes and discusses the significant implications of these advancements for pharmaceutical research and clinical application, supported by recent case studies and emerging trends.

Why Stereoselectivity Matters: Foundations for Drug Efficacy and Safety

FAQs: Core Concepts and Common Challenges

1. What is the fundamental difference between a stereoselective and a stereospecific reaction? A stereoselective reaction is one where a single reactant can form two or more stereoisomers, but one is preferentially produced over the others [1] [2]. The selectivity arises from differences in steric and electronic effects in the transition states leading to the different products [2]. In contrast, a stereospecific reaction is one where different stereoisomeric starting materials yield different stereoisomeric products. The mechanism dictates a fixed relationship between the stereochemistry of the reactant and the product [3]. A classic example is the SN2 reaction, which proceeds with inversion of configuration [3]. All stereospecific reactions are stereoselective, but not all stereoselective reactions are stereospecific [3].

2. In a reaction that creates a new chiral center, how can I tell if I have enantioselectivity or diastereoselectivity? The key is to examine the products. Enantioselectivity is observed when an achiral starting material is converted into a chiral product, and one enantiomer is formed in preference to the other [2]. This typically requires a chiral influence in the system, such as a chiral catalyst, enzyme, or reagent [2]. Diastereoselectivity is observed when a reaction produces two or more diastereomers, and one is favored [2]. This often occurs when a new chiral center is formed in a molecule that already contains one or more pre-existing chiral centers, or in reactions like hydrogenation of alkenes that produce diastereomeric E/Z isomers [1] [2].

3. My asymmetric reaction is yielding a racemic mixture despite using a chiral catalyst. What is the most likely cause? The most common causes and their troubleshooting steps are outlined in the table below.

| Problem Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Deactivation | Analyze reaction mixture for catalyst decomposition products; test a fresh batch of catalyst. | Purify reagents/solvents to remove trace acids/water; run reaction under inert atmosphere. |

| Unfavorable Reaction Conditions | Screen a range of temperatures and solvents. | Lowering temperature often enhances selectivity; ensure solvent polarity matches catalyst requirements. |

| Poor Substrate/Catalyst Match | Check literature for similar substrate types with your catalyst system. | Consider screening a small library of chiral ligands/catalysts to find a better match. |

| Background Reaction | Run a control reaction without the chiral catalyst. | Modify catalyst structure to increase activity; adjust reagent concentrations to favor catalyzed pathway. |

4. How can I quantitatively report the success of my enantioselective or diastereoselective reaction?

The success of an enantioselective reaction is quantitatively reported as enantiomeric excess (e.e.), which is calculated from the relative amounts of the two enantiomers in the product mixture [3]. The success of a diastereoselective reaction is reported as diastereomeric excess (d.e.), which measures the excess of one diastereomer over the others in the mixture [2]. These values are calculated as follows:

e.e. = |[R] - [S]| / ([R] + [S]) × 100%

d.e. = |[Major diastereomer] - [Minor diastereomer]| / (Sum of all diastereomers) × 100%

These values are typically determined using analytical techniques like Chiral HPLC or NMR spectroscopy [3].

5. What are the main strategies to induce high stereoselectivity in a synthetic transformation? The three major strategies, which have evolved over time, are [4]:

- Substrate Control: Utilizing pre-existing chirality within the starting material to direct the formation of new stereocenters. This includes the use of chiral auxiliaries [4].

- Reagent Control: Employing a stoichiometric chiral reagent to enforce stereoselectivity in the reaction of an achiral substrate [4].

- Catalyst Control (Asymmetric Catalysis): Using a small, catalytic amount of a chiral catalyst to bias the reaction pathway toward the desired stereoisomer. This is often the most efficient method and includes metal-based catalysts (e.g., Noyori's BINAP-Ru for hydrogenation) and organocatalysts (e.g., proline for aldol reactions) [3] [4].

Troubleshooting Guide: Low or Unexpected Stereoselectivity

Low stereoselectivity is a common challenge. The following workflow provides a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving these issues.

Detailed Troubleshooting Steps

Step 1: Verify Product Analysis Ensure your analytical methods are accurately distinguishing stereoisomers. Use multiple techniques if necessary:

- For enantioselectivity: Chiral HPLC or GC is standard.

- For diastereoselectivity: NMR (e.g., ^1H or ^19F) is often sufficient, but HPLC on an achiral column can also be effective.

Step 2: Check Catalyst and Reagent Integrity Chiral catalysts, especially metal complexes with chiral ligands, can be air- or moisture-sensitive, leading to decomposition and loss of selectivity [3].

- Action: Use fresh batches of catalysts and ligands. Ensure solvents and reagents are dry and free of impurities. Perform reactions under an inert atmosphere (e.g., N₂ or Ar) when required.

Step 3: Run a Control Experiment Perform the reaction in the absence of the chiral catalyst or reagent.

- Interpretation: If the reaction proceeds at a similar rate, a significant background reaction is occurring, which is inherently non-selective and will erode your e.e. or d.e. [3].

- Solution: Modify reaction conditions to favor the catalyzed pathway. This may involve increasing catalyst loading, changing the catalyst to a more active variant, or altering concentration and temperature.

Step 4: Screen Key Reaction Parameters If no background reaction is detected, the selectivity is solely dependent on the chiral influence but is suboptimal. Systematically screen:

- Temperature: Lowering the reaction temperature is one of the most effective ways to improve stereoselectivity, as it increases the energy difference between the diastereomeric transition states [1].

- Solvent: Solvent polarity and hydrogen-bonding capability can dramatically influence transition state stability. A full solvent screen is often invaluable.

- Concentration and Additives: Small changes in concentration or the addition of molecular sieves, salts, or weak acids/bases can have a profound effect.

Step 5: Re-evaluate the Catalyst-Substrate Match If optimization fails, the core issue may be that the chiral catalyst's environment is not providing sufficient steric bias or the correct non-covalent interactions for your specific substrate.

- Action: Consult the literature for catalysts known to work well with your substrate class. If resources allow, initiate a high-throughput screen of a diverse chiral ligand library [4].

Featured Experimental Protocol: Evans Aldol Reaction with a Chiral Auxiliary

This protocol exemplifies the substrate control strategy for achieving high diastereoselectivity using a chiral auxiliary [3] [4].

Objective

To synthesize a syn-aldol product with high diastereomeric control using an Evans oxazolidinone chiral auxiliary.

Materials and Reagents

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role |

|---|---|

| (S)-4-Isopropyl-1,3-oxazolidin-2-one | Chiral Auxiliary. Provides a rigid template for enolate formation and sterically shields one face of the molecule, enabling high facial selectivity during the aldol addition [3]. |

| Propionyl Chloride | Substrate Acyl Donor. Forms the substrate-bearing N-acyl oxazolidinone upon coupling with the auxiliary. |

| Dibutylboron Triflate (Bu₂BOTf) | Lewis Acid. Forms a chelated (Z)-enolate with the N-acyl oxazolidinone, creating a rigid transition state crucial for high selectivity [4]. |

| N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) | Non-Nucleophilic Base. Deprotonates the enolizable position to generate the boron enolate. |

| Benzaldehyde | Aldehyde Electrophile. The partner aldehyde in the aldol addition. |

| Methanol, pH 7 Buffer | Mild Aqueous Workup. Gently cleaves the boron-oxygen bond post-reaction without epimerizing the newly formed stereocenters. |

| Lithium Hydroperoxide (LiOOH) | Auxiliary Cleavage Reagent. Cleaves the auxiliary from the desired aldol product under basic oxidative conditions, yielding the corresponding carboxylic acid [3]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Coupling: Dissolve the (S)-4-isopropyl-1,3-oxazolidin-2-one (1.0 equiv) in dry THF under N₂. Cool to 0°C and add n-BuLi (1.05 equiv). Stir for 30 minutes. Add propionyl chloride (1.1 equiv) dropwise. Warm to room temperature and stir until complete by TLC. Work up with aqueous NH₄Cl and extract with ethyl acetate. Purify the product by flash chromatography to obtain the propionyl-oxazolidinone.

Enolate Formation: Dissolve the propionyl-oxazolidinone (1.0 equiv) in dry CH₂Cl₂ under N₂. Cool to -78°C. Add DIPEA (1.2 equiv) followed by dibutylboron triflate (1.1 equiv). Stir for 1 hour at -78°C to form the chelated (Z)-boron enolate.

Aldol Addition: Add benzaldehyde (1.5 equiv) dropwise to the enolate solution at -78°C. Maintain the temperature and monitor by TLC. The reaction is typically complete within 1-2 hours.

Workup: Quench the reaction by careful addition of a 1:1 mixture of pH 7 phosphate buffer and methanol. Allow the mixture to warm to 0°C and stir for 1 hour. Extract the aqueous layer with CH₂Cl₂, dry the combined organic layers (MgSO₄), and concentrate under reduced pressure.

Auxiliary Cleavage: Take the crude aldol adduct and dissolve in a THF/water mixture. Cool to 0°C and add 30% H₂O₂ (excess) followed by LiOH•H₂O (2.0 equiv). Stir vigorously at 0°C until the starting material is consumed. Acidify carefully with 1M KHSO₄ and extract with ethyl acetate. Dry and concentrate to yield the syn-aldol product as a carboxylic acid.

Key Technique Notes

- Diastereoselectivity: This protocol reliably provides >95:5 d.r. for the syn-aldol product due to the highly ordered Zimmerman-Traxler transition state enforced by the chiral auxiliary and boron chelation [4].

- Analysis: Determine the d.r. by ^1H NMR analysis of the crude product before cleavage or by HPLC.

- Safety: All steps prior to workup must be performed under a strict inert atmosphere using anhydrous solvents. Handle boron triflate and n-BuLi with appropriate precautions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Stereoselective Synthesis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role |

|---|---|

| Noyori's BINAP-Ru Catalyst | A metal-based chiral catalyst for highly enantioselective hydrogenation of ketones and alkenes (e.g., in the synthesis of (S)-Naproxen) [3]. |

| Jacobsen's Salen (Mn) Catalyst | A chiral catalyst for the enantioselective epoxidation of unfunctionalized alkenes [3]. |

| Sharpless Dihydroxylation Reagents | A system using OsO₄ and chiral cinchona alkaloid ligands (e.g., (DHQ)₂PHAL) for the enantioselective conversion of alkenes to diols [3]. |

| CBS Oxazaborolidine Catalyst | An organocatalyst for the highly enantioselective reduction of prochiral ketones to secondary alcohols [3]. |

| Evans Oxazolidinone Auxiliaries | Chiral auxiliaries used in substrate-controlled diastereoselective reactions, most famously for aldol reactions and enolate alkylations [3] [4]. |

| Enzymes (e.g., Lipases, Ketoreductases) | Biological catalysts often used in kinetic resolutions or asymmetric synthesis, providing exceptionally high levels of stereoselectivity under mild conditions [5]. |

Advanced Concepts and Future Directions

The field of stereoselective synthesis is continuously advancing. Modern approaches are increasingly leveraging computational tools and artificial intelligence to predict stereochemical outcomes and design new catalysts [5] [4]. Machine learning (ML) models are now being trained on large datasets of asymmetric reactions to predict the enantioselectivity that a given chiral catalyst will impart on a specific substrate [4]. Furthermore, the integration of high-throughput experimentation (HTE) with automated synthesis and analysis allows for the rapid screening of thousands of reaction conditions to identify optimal stereoselectivity, a process that was previously time-consuming and labor-intensive [5] [4]. These technologies represent the cutting edge in the ongoing thesis of improving stereoselectivity in synthetic research.

In medicinal chemistry, stereochemistry is not merely an academic concern; it is a fundamental determinant of drug safety and efficacy. Many drugs are chiral molecules, meaning they exist as two non-superimposable mirror images, much like a left and right hand. These mirror images, called enantiomers, can exhibit vastly different pharmacological behaviors within the human body, which is itself a chiral environment composed of chiral proteins, receptors, and enzymes [6] [7].

The two enantiomers of a chiral drug must be considered two different drugs with distinct properties [6]. For researchers working on asymmetric synthesis, understanding this pharmacological imperative is crucial. The goal is not just to achieve stereoselectivity, but to produce the specific enantiomer that delivers the desired therapeutic effect while minimizing or eliminating the potential for adverse effects contributed by its mirror image [7].

Core Concepts: Eutomers, Distomers, and the Eudismic Ratio

To systematically discuss stereoselectivity in pharmacology, scientists use specific terminology:

- Eutomer: The enantiomer with the higher desired pharmacological activity [7].

- Distomer: The enantiomer with the lower desired activity or undesirable effects [7].

- Eudismic Ratio: The ratio of activities between the eutomer and distomer. A high eudismic ratio indicates a large difference in potency and provides a strong argument for developing a single-enantiomer drug [7].

The interaction between a chiral drug and its biological target is often explained using a "lock-and-key" model, where the chiral binding site on a receptor or enzyme can distinguish between the two enantiomers. The following diagram illustrates why one enantiomer may bind effectively while the other does not.

Quantitative Data: Stereochemistry Impact on Drug Properties

The differences between enantiomers are not just theoretical; they are quantifiable across key pharmacological parameters. The table below summarizes critical data from well-known chiral drugs, demonstrating the spectrum of stereochemical influences.

Table 1: Pharmacological Profiles of Selected Chiral Drugs

| Drug (Racemate) | Active Enantiomer | Inactive/Other Enantiomer | Key Pharmacological Differences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propranolol [7] | (S)-Propranolol | (R)-Propranolol | (S)-enantiomer is a potent β-blocker; (R)-enantiomer is ~100-fold less active at β-receptors. |

| Warfarin [7] | (S)-Warfarin | (R)-Warfarin | (S)-enantiomer is 3-5x more potent as an anticoagulant. Metabolized primarily by CYP2C9, leading to complex PK. |

| Ibuprofen [7] | (S)-Ibuprofen | (R)-Ibuprofen | Only (S) inhibits COX-1/2. (R) is largely inactive but undergoes partial in vivo chiral inversion to (S). |

| Sotalol [6] [7] | Racemate used | N/A | (-)-enantiomer is a β-blocker (Class II). (+)-enantiomer is a K+ channel blocker (Class III). Racemate has both actions. |

| Thalidomide [7] | (R)-Thalidomide (intended sedative) | (S)-Thalidomide (teratogenic) | (S)-enantiomer causes birth defects. However, racemization in vivo means single-enantiomer administration is not safe. |

| Omeprazole [6] [7] | Both are active | N/A | (S)-Enantiomer (Esomeprazole) is metabolized more slowly, providing higher, more consistent plasma levels. |

PK = Pharmacokinetics; COX = Cyclooxygenase

The Scientist's Toolkit: Reagents & Methods for Asymmetric Synthesis

Developing a single-enantiomer drug requires synthetic methods that can preferentially produce one enantiomer. The following table lists key tools and strategies used in asymmetric synthesis.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Methodologies for Asymmetric Synthesis

| Tool/Methodology | Brief Description | Function in Stereoselective Research |

|---|---|---|

| Chiral Catalysts [8] [9] | Metal complexes with chiral ligands (e.g., BINOL) or organocatalysts. | Create a chiral environment to favor formation of one enantiomer over the other in reactions like hydrogenation. |

| Chiral Auxiliaries [9] [10] | A temporary chiral group attached to a substrate. | Controls stereochemistry during a key reaction step; removed after serving its purpose. |

| Chiral Pool Synthesis [8] | Using readily available chiral natural products (e.g., sugars, amino acids) as starting materials. | Transfers chirality from a natural molecule to the synthetic target, simplifying stereocontrol. |

| Biocatalysts [11] | Enzymes (e.g., engineered amine dehydrogenases) or whole cells. | Leverages the innate chirality and high selectivity of enzymes for asymmetric transformations. |

| Sn-Beta Zeolite [11] | A tin-substituted microporous silicate. | An inorganic catalyst used with borate salts for the selective epimerization of sugars, an alternative to enzymes. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs for Stereoselective Research

This section addresses common experimental challenges and provides detailed protocols to guide your work.

FAQ 1: Why is a High Eudismic Ratio (ER) a Key Goal in Lead Optimization?

A high eudismic ratio indicates that the biological activity is highly stereoselective. This is desirable because:

- Potency & Dose: A high-ER compound means the eutomer is responsible for most of the activity, allowing for lower dosing [7].

- Purity Profile: Developing the single eutomer eliminates the "isomeric ballast" of the distomer, which could contribute to off-target effects, toxicity, or unpredictable pharmacokinetics [6] [7].

- Clear Mechanism: A high ER often suggests a specific, single-mode interaction with the target, simplifying the understanding of the drug's mechanism of action.

FAQ 2: When is it Acceptable to Develop a Racemate Instead of a Single Enantiomer?

The decision to develop a racemate (a 50:50 mixture of enantiomers) must be scientifically justified. A racemate may be acceptable if [6] [7]:

- Both Enantiomers are Therapeutically Useful: As seen with sotalol, where each enantiomer contributes a different, desired pharmacological action.

- There is Rapid In Vivo Interconversion: As with ibuprofen, where the inactive (R)-enantiomer is converted to the active (S)-form in the body.

- The Distomer is Inert and Safe: If the distomer is completely inactive and does not interfere with the eutomer's pharmacokinetics or safety profile, a racemate might be justified on cost-of-goods grounds. However, regulatory scrutiny is high.

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Poor Enantioselectivity in a Catalytic Reaction

Problem: Your catalytic asymmetric reaction is yielding product with low enantiomeric excess (ee).

| Possible Cause | Suggested Investigation & Solution |

|---|---|

| Impurity in Chiral Catalyst/Ligand | Check purity of ligand/catalyst. Re-purify or re-synthesize if necessary. |

| Solvent Effects | Screen different solvents. The polarity and protic/aprotic nature of the solvent can dramatically influence transition state energies and selectivity. |

| Trace Metal or Water Contamination | Ensure all glassware is scrupulously clean. Use anhydrous solvents and conduct reactions under inert atmosphere. |

| Substrate Scope Limitation | The chosen catalytic system may not be optimal for your specific substrate. Explore different classes of chiral catalysts (e.g., switch from a phosphine ligand to a bisoxazoline ligand). |

| Non-Linear Effects | In some cases, the enantiopurity of the product is not linearly related to the enantiopurity of the catalyst. Use a catalyst with >99% ee. |

Troubleshooting Guide 2: UnexpectedIn VivoToxicity or PK Despite GoodIn VitroSelectivity

Problem: Your single enantiomer candidate shows excellent in vitro target selectivity but has unexpected toxicity or complex pharmacokinetics in animal models.

| Possible Cause | Suggested Investigation & Solution |

|---|---|

| In Vivo Racemization | Check plasma and tissue samples for the appearance of the other enantiomer over time. If occurring, the molecule may not be suitable for single-enantiomer development. |

| Enantioselective Metabolism | The enantiomer may be metabolized to a toxic species. Conduct in vitro metabolism studies with liver microsomes/ hepatocytes to identify and characterize metabolites [12]. |

| Off-Target Binding of Metabolites | A metabolite, not the parent drug, could be binding to an off-target receptor. Identify major metabolites and screen them for pharmacological activity. |

| Enantiomer-Specific Protein Binding | One enantiomer may bind more strongly to plasma proteins, altering the free fraction of the drug and its distribution [7] [12]. |

Experimental Protocol 1: Assessing Enantioselective Metabolism Using Liver Microsomes

Objective: To determine if the metabolism of your chiral drug candidate is stereoselective.

Materials:

- Test compound (single enantiomer or racemate)

- Pooled human or species-specific liver microsomes

- NADPH regenerating system

- Phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Stopping solution (e.g., acetonitrile with internal standard)

- Chiral HPLC or LC-MS/MS system

Methodology:

- Incubation Preparation: Prepare incubation mixtures containing liver microsomes (e.g., 0.5 mg/mL protein), phosphate buffer, and your test compound at a physiologically relevant concentration.

- Pre-Incubation: Allow the mixture to equilibrate for 5 minutes at 37°C in a shaking water bath.

- Initiate Reaction: Start the reaction by adding the NADPH regenerating system.

- Time Points: At predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 minutes), remove an aliquot and quench the reaction with ice-cold stopping solution.

- Sample Analysis: Centrifuge the quenched samples to precipitate proteins. Analyze the supernatant using a validated chiral analytical method (HPLC or LC-MS/MS) to quantify the remaining parent enantiomers and any chiral metabolites.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the half-life (t₁/₂) and intrinsic clearance (CLᵢₙₜ) for each enantiomer separately. A significant difference in these parameters confirms enantioselective metabolism [12].

The metabolic pathways for each enantiomer can be distinct, as visualized in the following workflow for a racemic drug.

Experimental Protocol 2: Determining Eudismic Ratio viaIn VitroReceptor Binding

Objective: To quantitatively compare the affinity of two enantiomers for a target receptor.

Materials:

- Purified drug target (receptor, enzyme)

- Radio-labeled or fluorescently labeled reference ligand

- Test compounds: Eutomer and Distomer (highly purified)

- Assay buffer

- Filtration apparatus or other detection instrumentation

Methodology:

- Incubation Setup: In a multi-well plate, prepare a constant concentration of the target and the labeled ligand. Add increasing concentrations of your unlabeled test enantiomers to separate wells (in triplicate) to create a competition curve. Include wells for total binding (no competitor) and nonspecific binding (with a large excess of unlabeled standard ligand).

- Equilibration: Incubate the plate under appropriate conditions (time, temperature) to allow the binding reaction to reach equilibrium.

- Separation & Measurement: Separate the bound ligand from the free ligand (e.g., by rapid filtration). Measure the amount of bound labeled ligand in each well.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the percentage of bound ligand inhibited by each concentration of your test enantiomers.

- Plot the data and fit a curve to determine the IC₅₀ (concentration that inhibits 50% of specific binding) for each enantiomer.

- The Eudismic Ratio is calculated as: ER = IC₅₀(Distomer) / IC₅₀(Eutomer) [7].

- A ratio significantly greater than 1 indicates stereoselective binding.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

Understanding Stereoselective Metabolism

1. What is stereoselective metabolism and why is it critical in drug development? Stereoselective metabolism occurs when enzymatic systems, such as Cytochrome P450s (CYPs) and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs), preferentially metabolize one enantiomer of a chiral drug over the other. This is critical because each enantiomer can have distinct pharmacological activities, toxicity profiles, and bioavailability. Assessing stereoselectivity is essential for understanding a drug's efficacy, tolerability, safety, and potential for drug-drug interactions [13]. Ignoring stereoselectivity can lead to clinical non-response or adverse reactions.

2. Which CYP families are most involved in stereoselective xenobiotic metabolism? The CYP1, CYP2, and CYP3 families are predominantly responsible for the stereoselective metabolism of xenobiotics and many pharmaceuticals. These enzymes exhibit remarkable catalytic versatility and substrate promiscuity, enabling them to perform a wide range of stereo- and regioselective oxidative transformations [14] [15].

3. Beyond the liver, where else might stereoselective metabolism impact drug action? CYP enzymes are expressed in various extrahepatic tissues, including the brain. Although total cerebral CYP levels are lower than in the liver, their specific localization in different brain regions and cell types (e.g., specific neurons and glia) allows them to significantly influence local concentrations of neuroactive drugs, toxins, and endogenous compounds like neurotransmitters and neurosteroids. This local metabolism can directly impact drug efficacy and neurological health [15].

Troubleshooting Experimental Challenges

4. My chiral analytical methods are inconsistent. What are the primary challenges? Analytical techniques for assessing stereoselectivity present several common challenges:

- Indirect Chromatographic Methods: These are only applicable to specific samples with functional groups that can be derivatized or form complexes with a chiral selector.

- Direct Chromatographic Methods: Using Chiral Stationary Phases (CSPs) is effective but can be expensive.

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): While highly sensitive and specific, MS can still suffer from matrix interference. Careful method validation and selection of the appropriate technique based on your compound's properties are crucial for reliable data [13].

5. How can I engineer a CYP enzyme to alter its stereoselectivity? The stereoselectivity of CYP enzymes can be engineered through rational design and directed evolution. Key strategies include:

- Modulating Heme Redox Potential: Substituting residues that coordinate the heme iron or surround the heme group can alter the redox potential, thereby changing the reaction selectivity, stereoselectivity, and even the type of chemical reaction the enzyme catalyzes [14].

- Reshaping the Substrate-Binding Pocket: Mutagenesis of residues in the catalytic pocket can directly influence how the substrate is positioned, thus affecting regio- and stereoselectivity. Advanced techniques like site-specific mutagenesis with non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs) can create bulky substitutions that reshape the binding pocket in ways the 20 standard amino acids cannot, potentially unlocking unnatural activities and altering selectivity [16].

6. Can I use hydrogen peroxide instead of NADPH for P450-mediated reactions? Yes, in some cases. Through rational engineering, some NADPH-dependent P450 monooxygenases have been successfully converted into H₂O₂-dependent peroxygenases. This can be a more cost-effective strategy as H₂O₂ is less expensive than the NADPH cofactor and its regeneration system [14]. This is known as utilizing the "peroxide shunt" pathway.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing and Engineering Stereoselectivity

Protocol 1: Assessing Stereoselective Metabolite Formation using Chiral Chromatography

This protocol outlines a standard method for separating and quantifying the enantiomers of a drug and its metabolites.

1. Principle: A chiral chromatographic method separates enantiomers based on their differential interaction with a chiral selector in the stationary phase. The relative peak areas or heights of the enantiomers are used to determine enantiomeric excess (ee) and quantify stereoselective metabolism.

2. Reagents and Materials:

- Test compound (chiral drug)

- Metabolic incubation system (e.g., liver microsomes, recombinant CYP/UGT enzyme, NADPH regenerating system for CYPs, UDPGA for UGTs)

- Appropriate buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 7.4)

- Termination solvent (e.g., acetonitrile, methanol)

- Chiral HPLC or UPLC column (e.g., Chiralpak, Chiralcel)

- HPLC/UPLC system with UV, fluorescence, or mass spectrometric detection

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Incubation. Set up metabolic incubations containing your enzyme system and test compound. Run control incubations without cofactors or with heat-inactivated enzyme.

- Step 2: Termination. At predetermined time points, terminate the reaction by adding a volume of cold termination solvent. Vortex and centrifuge to precipitate proteins.

- Step 3: Sample Analysis. Inject the supernatant onto the chiral chromatographic system. Use an isocratic or gradient method optimized for your specific compound.

- Step 4: Data Analysis.

- Identify the peaks corresponding to each enantiomer of the parent drug and its metabolites using authentic standards.

- Calculate the enantiomeric ratio (ER) or enantiomeric excess (ee) for the substrate and metabolites.

- Enantiomeric Excess (ee) = [ (Major - Minor) / (Major + Minor) ] × 100%

4. Troubleshooting Tips:

- Poor Peak Resolution: Optimize the mobile phase composition (e.g., ratio of organic solvent, type and concentration of additives like acids or amines), column temperature, and flow rate.

- Low Sensitivity: Consider derivatization with a chiral reagent to introduce a fluorophore for more sensitive detection, or switch to a more sensitive detector like MS.

- Long Run Times: Screen different chiral columns to find one that provides adequate resolution in a shorter time.

Protocol 2: Rational Engineering of a P450 for Altered Stereoselectivity

This protocol describes a structure-guided approach to engineer P450 stereoselectivity by targeting the substrate-access channel or active site [14] [16].

1. Principle: Based on a crystal structure or a robust homology model, specific residues that interact with the substrate or influence heme electronics are targeted for mutagenesis to alter the enzyme's stereo-preference.

2. Reagents and Materials:

- Plasmid DNA encoding the wild-type P450 enzyme

- Site-directed mutagenesis kit

- Competent E. coli cells (e.g., BL21)

- LB media and antibiotics

- Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)

- δ-Aminolevulinic acid (ALA)

- Lysis buffer

- Test substrate

- NADPH or H₂O₂

- Analytical equipment (HPLC, LC-MS)

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Target Identification. Analyze the enzyme's 3D structure to identify residues that line the substrate-binding pocket, coordinate the heme iron, or are part of the substrate-access channel. Residues like P450BM3's F393, which is near the heme-coordinating cysteine, are prime targets [14].

- Step 2: Library Design. Design a set of point mutations. Consider substituting residues with ones that have different sizes, charges, or hydrophobicities. For advanced engineering, consider ncAA incorporation to introduce unique functional groups [16].

- Step 3: Mutant Generation. Perform site-directed mutagenesis to create the variant library. Transform the plasmids into an appropriate E. coli expression host.

- Step 4: Expression and Screening.

- Inoculate cultures and induce protein expression with IPTG. Supplement with ALA to enhance heme production.

- Harvest cells, lyse, and use the crude lysate or purified protein in activity assays with your target substrate.

- Analyze the products using the chiral methods from Protocol 1 to determine changes in stereoselectivity and activity compared to the wild-type enzyme.

4. Troubleshooting Tips:

- Low Protein Expression: Optimize induction conditions (IPTG concentration, temperature, induction time). Check protein sequence for potential misfolding.

- No Activity: Confirm heme incorporation (check for a Soret peak at ~450 nm in the CO-difference spectrum). Ensure the cofactor (NADPH or H₂O₂) is functional and concentrations are correct.

- No Change in Selectivity: Expand the mutagenesis library to target different residues or use saturation mutagenesis to explore all possible substitutions at a key position.

Quantitative Data on CYP Engineering and Analysis

Table 1: Impact of Key Residue Mutations on P450BM3 Properties and Activity [14]

| P450BM3 Variant | Heme Redox Potential (mV) | Catalytic Competency vs. Wild-Type | Key Structural Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type | -427 (substrate-free) | Baseline | Reference scaffold |

| F393Y | Similar to wild-type | Highly similar | Substitution with physicochemically equivalent residue |

| F393H | Not Reported | Reduced | Substitution with non-equivalent residue, affects heme environment |

| F393A | Not Reported | Reduced | Substitution with non-equivalent residue, creates space in heme pocket |

Table 2: Comparison of Analytical Methods for Assessing Stereoselectivity in Drug Metabolism [13]

| Analytical Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages/Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect Chromatography | Derivatization with a chiral reagent to form diastereomers. | Can use standard (achiral) HPLC columns. | Only applicable to compounds with specific functional groups. |

| Direct Chromatography (CSPs) | Direct separation on a chiral stationary phase. | Broad applicability, high efficiency. | Expensive columns, may require extensive mobile phase optimization. |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Detection based on mass-to-charge ratio. | Highly sensitive and specific. | Matrix interference can be a challenge; does not distinguish enantiomers without separation. |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Use of chiral solvating agents. | Provides structural information. | Can be less sensitive than chromatographic methods. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying CYP-Mediated Stereoselective Metabolism

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant CYP Enzymes | Isoform-specific metabolism studies; eliminates interference from other enzymes. | Identifying which specific CYP (e.g., CYP2D6, CYP3A4) is responsible for the stereoselective metabolism of a new drug candidate. |

| Chiral Stationary Phases (CSPs) | High-resolution separation of enantiomers for analytical or preparative purposes. | Quantifying the enantiomeric excess (ee) of a metabolite produced by a engineered CYP variant. |

| NADPH Regeneration System | Provides a continuous supply of NADPH for CYP monooxygenase activity in in vitro incubations. | Supporting long-term metabolic stability assays with liver microsomes or purified CYPs. |

| Non-Canonical Amino Acids (ncAAs) | Incorporation via mutagenesis to introduce novel chemical functionalities into enzymes. | Radically reshaping a P450's active site to accept an unnatural substrate or alter its stereoselectivity [16]. |

| Chemical Decoys / Substrate Mimetics | Small molecules that bind the active site and redirect the enzyme's reactivity toward non-native substrates. | Enabling regio- and stereoselective hydroxylation of small molecules by P450s like P450BM3 via the peroxide shunt pathway [14]. |

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

CYP Engineering Workflow

Analytical Method Selection

The global pharmaceutical landscape has undergone a fundamental transformation in its approach to chiral drugs, with regulatory agencies establishing a clear preference for single-enantiomer development over racemic mixtures. This shift stems from the profound recognition that enantiomers, despite their chemical similarity, can exhibit dramatically different pharmacological activities, safety profiles, and therapeutic effects within the chiral environment of the human body. Regulatory bodies worldwide now require rigorous stereochemical characterization and justification for drug development decisions, creating both challenges and opportunities for pharmaceutical researchers and developers. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has not approved a racemate since 2016, while the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has averaged only one racemic approval per year from 2013 to 2022, typically under specific circumstances where stereochemistry does not significantly impact therapeutic activity [17].

This technical support guide addresses the critical experimental and analytical considerations for navigating this stringent regulatory environment, with a focus on troubleshooting common challenges in stereoselective synthesis and analysis. The content is framed within the broader context of improving stereoselectivity in asymmetric synthesis research, providing practical methodologies for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working to meet evolving regulatory standards for enantiopure pharmaceuticals.

FAQ: Understanding the Regulatory Framework

Q1: What is the current regulatory stance on developing racemic mixtures versus single enantiomers?

Regulatory agencies strongly favor the development of single-enantiomer drugs unless compelling scientific justification supports developing a racemate. According to FDA requirements, decisions to develop drugs as single enantiomers versus racemates must be scientifically justified in drug approval applications [17]. The policy allows continued development of racemic mixtures only when sufficient pharmacological, toxicological, and pharmacokinetic justification demonstrates that the racemate would be superior to a single stereoisomer. Between 2013 and 2022, 59% of FDA-approved new small-molecule drugs were single-enantiomer medicines, compared to just 3.6% racemic mixtures—a sharp increase from previous decades [18].

Q2: What specific requirements do regulators have for chiral switches?

A chiral switch—developing a single-enantiomer version of an already approved racemic drug—faces stringent regulatory expectations. The single-enantiomer product is typically treated as a new molecular entity (NME), requiring a full New Drug Application (NDA) or Marketing Authorization Application (MAA), not a simple supplemental application [19]. Companies must provide comprehensive nonclinical, clinical, and Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) data packages. Critically, they must demonstrate that the single enantiomer provides clinically meaningful advantages—not just chemical purity—often through comparative efficacy studies against the racemate [19]. Failure to prove clear advantages can lead to regulatory challenges or market skepticism.

Q3: How has the approval trend for chiral drugs evolved recently?

Recent analysis of new drug approvals reveals striking trends. The European Medicines Agency has maintained particularly stringent standards, having not approved a single racemate since 2016 [17]. Analysis of FDA approvals from 2013 to 2022 shows that only two chiral switches were identified during this period, both combined with drug repurposing strategies [17]. This indicates that regulatory pathways for chiral switches have become more challenging, requiring demonstration of significant clinical benefit beyond mere enantiomeric purity.

Q4: What analytical validation is required for chiral drug submissions?

Regulatory submissions for chiral drugs require rigorous enantiomeric purity assessment and validation. Chiral purity assays typically operate in area percent quantitation mode to determine the abundance of undesired enantiomers relative to total peak area for both stereoisomers [17]. These supplementary assays complement principal purity determinations and must meet stringent regulatory requirements for impurity reporting, identification, and safety qualification. Method validation for chiral purity assays must include accuracy, precision, linearity, range, specificity, and robustness, with studies demonstrating correlation coefficients exceeding 0.98 and relative errors below 5% [17].

Troubleshooting Guides for Stereoselective Synthesis and Analysis

Troubleshooting Low Enantiomeric Excess (ee) in Asymmetric Synthesis

Problem: Inconsistent or low enantiomeric excess in asymmetric synthesis reactions.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Impurities in starting materials or catalysts deactivating chiral catalysts.

- Solution: Implement rigorous quality control for all starting materials using chiral HPLC or GC analysis. Ensure solvent purity and eliminate trace moisture or oxygen when working with air-sensitive catalysts [20].

- Protocol: Characterize starting material enantiopurity using validated chiral HPLC methods. For method development, screen multiple chiral columns (polysaccharide-based, cyclodextrin, etc.) with different mobile phase compositions to achieve baseline separation.

Cause 2: Suboptimal reaction conditions (temperature, concentration, solvent).

- Solution: Systematically optimize reaction parameters using design of experiments (DoE) approaches. Screen chiral ligands or catalysts at different temperatures (0°C to 60°C) and in various solvents (THF, DCM, toluene, MeOH) to identify optimal stereoselectivity [20].

- Protocol: Set up parallel reactions in different solvents with controlled atmosphere. Monitor reaction progress and ee simultaneously using chiral analytical methods.

Cause 3: Catalyst decomposition or non-linear effects.

- Solution: Characterize catalyst stability under reaction conditions using techniques like in-situ IR or NMR spectroscopy. Implement catalyst stabilization strategies if decomposition is observed [20].

- Protocol: Monitor catalyst integrity throughout the reaction using appropriate analytical techniques. Test for non-linear effects by running reactions with catalysts of varying enantiopurity.

Troubleshooting Chiral Separation Method Development

Problem: Inadequate resolution of enantiomers during analytical method development.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Incorrect chiral stationary phase selection.

- Solution: Implement systematic column screening protocols. Begin with versatile polysaccharide-based columns (CHIRALPAK/CHIRALCEL series), which address approximately 80% of chiral separations, then progress to other chemistries if needed [18] [21].

- Protocol: Use column screening kits containing 3-5 different chiral stationary phases. Screen in normal-phase, polar organic, and reversed-phase modes if applicable. New immobilized phases like CHIRALPAK IJ offer broader solvent compatibility [18].

Cause 2: Suboptimal mobile phase composition.

- Solution: Systematically optimize mobile phase composition, organic modifier percentage, acid/base additives, and column temperature [17].

- Protocol: For normal-phase separations, screen hexane/ethanol or hexane/isopropanol mixtures with 0.1% acidic (trifluoroacetic acid, formic acid) or basic (diethylamine, triethylamine) additives. For reversed-phase, screen methanol/water or acetonitrile/water mixtures with similar additives.

Cause 3: Insufficient detection sensitivity for trace enantiomeric impurities.

- Solution: Enhance detection using LC-MS/MS or other advanced detection methods [17].

- Protocol: Develop LC-MS/MS methods using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) for specific detection of trace enantiomeric impurities. This approach virtually eliminates interference from endogenous substances and co-administered drugs.

Table 1: Chiral Stationary Phases for Method Development

| Stationary Phase Type | Common Applications | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polysaccharide-based (CHIRALPAK/CHIRALCEL) | Broad applicability, ~80% of chiral separations [18] | Wide enantioselectivity range, various derivatives available | Traditional coated phases have limited solvent compatibility |

| Immobilized polysaccharide (CHIRALPAK IJ) | Extended solvent compatibility [18] | Compatible with broader range of mobile phases including HPLC and SFC solvents | Potentially higher cost |

| Cyclodextrin-based | Small molecules, ionizable compounds | Good for reversed-phase applications | Limited capacity for preparative scale |

| Macrocyclic glycopeptide | Ionizable compounds, diverse applications | Complementary selectivity to polysaccharide phases | Narrower application range |

Troubleshooting Scalability Issues in Chiral Synthesis

Problem: Successful laboratory-scale synthesis fails during scale-up to pilot or production scale.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Mass and heat transfer limitations at larger scales.

- Solution: Implement engineering analysis and modify reaction equipment or conditions accordingly [22].

- Protocol: Conduct calorimetry studies to understand heat flow requirements. Optimize mixing parameters and reactor design to maintain consistent reaction environment.

Cause 2: Accumulation of trace impurities affecting catalyst performance.

- Solution: Enhance purification of starting materials and implement in-process purification steps [22].

- Protocol: Develop crystallization, extraction, or chromatography protocols for key intermediates. Monitor impurity profiles throughout the process using HPLC-MS.

Cause 3: Changes in enantioselectivity with increased concentration or modified mixing.

- Solution: Carefully map reaction parameter space during process development [22].

- Protocol: Use scale-down models to simulate large-scale conditions. Systemically vary concentration, mixing speed, and addition rates to identify critical process parameters.

Experimental Protocols for Key Chiral Analysis

Protocol: Chiral HPLC Method Development for Enantiomeric Separation

Principle: Utilize differential interaction between enantiomers and chiral stationary phases to achieve separation based on three-dimensional configuration.

Materials:

- HPLC system with UV/UV-Vis/PDA detector

- Multiple chiral columns (e.g., CHIRALPAK IA, IB, IC, ID; CHIRALCEL OD, OJ)

- HPLC-grade solvents: n-hexane, ethanol, isopropanol, methanol, acetonitrile

- Additives: trifluoroacetic acid, formic acid, diethylamine, triethylamine

- Standards: Racemic mixture and individual enantiomers (if available)

Procedure:

- Initial Screening: Set up a screening protocol using 3-5 different chiral columns with 2-3 mobile phase systems (normal phase, polar organic, reversed-phase).

- Column Equilibrium: Equilibrate each column with initial mobile phase (e.g., n-hexane:ethanol, 90:10 v/v) for at least 30 minutes.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare sample solution at approximately 0.1-1.0 mg/mL in appropriate solvent.

- Initial Analysis: Inject sample using isocratic elution with detection at appropriate wavelength.

- Mobile Phase Optimization: If partial separation is observed, systematically optimize organic modifier percentage (5-50%), additive type and concentration (0.05-0.5%), and column temperature (20-40°C).

- Method Validation: Once separation is achieved, validate method for specificity, linearity, accuracy, precision, and robustness according to ICH guidelines.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If no separation is observed across all screened columns, consider derivatization with chiral reagents to form diastereomers.

- For peak tailing or poor efficiency, adjust additive type and concentration, or consider alternative organic modifiers.

- For rapid analysis needs, explore UHPLC-compatible chiral columns with sub-2-micron particles [21].

Protocol: Determination of Enantiomeric Excess Using Chiral HPLC

Principle: Quantify the ratio of enantiomers in a sample by comparing peak areas after chiral separation.

Materials:

- Validated chiral HPLC method

- Racemic standard for system suitability

- Test samples

Procedure:

- System Suitability: Inject racemic standard to ensure resolution (Rs > 1.5), precision (%RSD < 2%), and tailing factor (T ≤ 2.0).

- Sample Analysis: Inject test samples using validated method.

- Data Analysis: Integrate peak areas for both enantiomers.

- Calculation: Calculate enantiomeric excess using the formula: [ ee\% = \frac{|Area{major} - Area{minor}|}{Area{major} + Area{minor}} \times 100\% ]

Validation Parameters:

- Specificity: No interference from impurities or degradation products

- Linearity: R² ≥ 0.99 over relevant concentration range

- Precision: %RSD ≤ 2% for replicate injections

- Accuracy: 98-102% recovery for spiked samples

Quantitative Data on Chiral Chemicals and Single-Enantiomer Drugs

Table 2: Chiral Chemicals Market and Production Data (2024)

| Parameter | Value | Context/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Global Chiral Chemicals Market Size [23] | USD 78.8 Billion (2024) | Projected to reach USD 218.2 Billion by 2035 (9.7% CAGR) |

| Pharmaceutical Share of Chiral Chemical Consumption [22] | 72% of total volume | 61,500 metric tons used in pharmaceutical manufacturing |

| Single-Enantiomer vs. Racemic FDA Approvals (2013-2022) [18] | 59% single-enantiomer vs. 3.6% racemic | Dramatic increase from previous decade |

| Asymmetric Synthesis Method Share [22] | 49% of production (2024) | Increased from 43% in 2020, showing industry preference |

| Chiral Chromatography Columns Market [24] | USD 93.4 Million (2024) | Growing at 6.0% CAGR, projected to reach USD 139 Million by 2032 |

| Average Cost per kg of Enantiopure Compound [22] | $3,800–$5,400 | Varies based on molecular complexity |

Table 3: Regional Distribution of Chiral Chemical Production (2024) [22]

| Region | Production Share | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Asia-Pacific | 41% market share | China and India produced >25,000 metric tons combined; >320 manufacturing plants |

| North America | Leading market by value | Well-established pharmaceutical sector and stringent regulatory standards |

| Europe | 28% of total production | Germany, Switzerland, and UK as major contributors; >900 active chiral R&D projects |

| Middle East & Africa | 3,100 metric tons consumption | Primarily pharmaceutical applications; growth supported by imports |

Research Reagent Solutions for Stereoselective Research

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Chiral Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chiral HPLC Columns | Enantiomer separation and analysis | Polysaccharide-based (CHIRALPAK/CHIRALCEL), cyclodextrin, macrocyclic glycopeptide; Daicel dominates ~68% of global sales volume [24] |

| Chiral Catalysts & Ligands | Asymmetric synthesis | BINAP, SALEN ligands, chiral phosphines; Johnson Matthey introduced enantioselective catalysts enabling >99.5% ee [22] |

| Chiral Solvents & Additives | Mobile phase optimization | Hexane, ethanol, isopropanol with acidic/basic additives (TFA, DEA) for chiral HPLC [17] |

| Enzymes for Biocatalysis | Sustainable chiral synthesis | Codexis transaminase enzyme used to produce 1,200 metric tons of chiral amines in 2024 [22] |

| Chiral Building Blocks | Synthesis of enantiopure APIs | BASF launched novel chiral building blocks adopted by 10 major pharma manufacturers [22] |

Workflow Visualization for Chiral Drug Development

Diagram Title: Chiral Drug Development Workflow

Diagram Title: Chiral Analysis Method Development

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How can I improve enantioselectivity with sterically demanding substrates?

Problem: A catalytic asymmetric conjugate addition (ACA) works well with simple linear substrates but provides poor enantioselectivity (<50% ee) when using substrates with bulky tert-butyl β-substituents.

Solution: Redesign your phosphoramidite ligand using a Quantitative Structure-Selectivity Relationship (QSSR) workflow. Key to success is modifying the aliphatic R-group on the ligand to fine-tune steric properties, as enantioselectivity can more than double (from 3.8 kJ/mol to 7.7 kJ/mol ΔΔG‡) with seemingly minor changes (e.g., replacing an isopropyl with an isononyl group) [25].

Experimental Protocol:

- Ligand Synthesis and Screening: Synthesize a small, structurally diverse library of phosphoramidite ligands, varying the aliphatic R-group.

- Data Collection: Run your ACA reaction with each ligand and record the enantiomeric excess (ee) achieved.

- Model Building: Calculate molecular descriptors (e.g., steric and electronic parameters, lipophilicity

log P) for each ligand. Use multivariate linear regression to build a model correlating these descriptors with the observed enantioselectivity (ΔΔG⧧). - Prediction and Validation: Use the model to predict the performance of new, unsynthesized ligand structures. Synthesize the most promising candidates and test them. Iteratively refine the model with new data until the desired enantioselectivity is achieved (e.g., >95% ee) [25].

FAQ 2: Why does my reaction yield change from the endo to the exo product when I run it at a higher temperature?

Problem: A Diels-Alder reaction of cyclopentadiene with furan produces the endo isomer at room temperature but the exo isomer at 81°C over a long reaction time.

Solution: This is classic behavior for a reaction under kinetic control at low temperature shifting to thermodynamic control at elevated temperature. The endo product is the kinetic product, favored by a lower activation energy due to better orbital overlap in the transition state. The exo product is the thermodynamic product, being more stable due to reduced steric congestion. The system equilibrates to the more stable product at higher temperatures [26].

Experimental Protocol:

- To Maximize the Kinetic (endo) Product: Run the reaction at a low temperature (e.g., room temperature or below) for a short to moderate time.

- To Maximize the Thermodynamic (exo) Product: Run the reaction at an elevated temperature (e.g., 81°C or higher) for a longer time to allow the system to reach equilibrium [26].

FAQ 3: How can I selectively form the less substituted enolate?

Problem: Deprotonation of an unsymmetrical ketone yields a mixture of enolates, and you need to selectively form the less substituted (kinetic) enolate.

Solution: Employ kinetic control conditions. Use a strong, sterically demanding base (e.g., LDA) at low temperatures (-78 °C) in a aprotic solvent. The deprotonation occurs irreversibly at the most accessible (least sterically hindered) α-hydrogen [26] [27].

Experimental Protocol:

- Cool your unsymmetrical ketone (e.g., 2-methylcyclohexanone) in anhydrous THF to -78 °C.

- Slowly add 1.0 equivalent of a base like lithium diisopropylamide (LDA).

- Stir for 15-30 minutes at -78 °C before adding your electrophile.

- Using an inverse addition method (adding ketone to the base) with rapid mixing can further minimize equilibration and improve selectivity for the kinetic enolate [26].

Quantitative Data for Reaction Design

Table 1: A-Values for Common Substituents

A-values provide a quantitative measure of substituent steric bulk based on the equilibrium of monosubstituted cyclohexanes. A higher A-value indicates a greater preference for the equatorial position due to increased steric strain in the axial position [28].

| Substituent | A-value (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| H | 0 |

| CH₃ | 1.74 |

| CH₂CH₃ | 1.75 |

| CH(CH₃)₂ | 2.15 |

| C(CH₃)₃ | >4 |

Table 2: Ligand Cone Angles

The cone angle is a measure of the steric bulk of a ligand in coordination chemistry, defined as the solid angle formed with the metal at the vertex. Bulker ligands can create a more sterically hindered environment around the metal center, influencing selectivity [28].

| Ligand | Cone Angle (°) |

|---|---|

| PH₃ | 87 |

| P(OCH₃)₃ | 107 |

| P(CH₃)₃ | 118 |

| P(CH₂CH₃)₃ | 132 |

| P(C₆H₅)₃ | 145 |

| P(cyclo-C₆H₁₁)₃ | 179 |

| P(t-Bu)₃ | 182 |

| P(2,4,6-Me₃C₆H₂)₃ | 212 |

Table 3: Ceiling Temperatures (T_c) for Selected Monomers

Ceiling temperature is the temperature at which the rate of polymerization equals the rate of depolymerization. For reactions, it illustrates how temperature can dictate whether a reaction is under kinetic (low T) or thermodynamic (high T) control by influencing the reversibility of the process [28].

| Monomer | Ceiling Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|

| ethylene | 610 |

| isobutylene | 175 |

| 1,3-butadiene | 585 |

| isoprene | 466 |

| styrene | 395 |

| α-methylstyrene | 66 |

Diagnostic Diagrams

Reaction Control Flowchart

Ligand Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Phosphoramidite Ligands | Chiral ligands for transition metal catalysis (e.g., Cu) that create a stereoselective environment; their steric and electronic properties can be tuned to improve enantioselectivity with challenging substrates [25]. |

| Strong, Sterically Hindered Bases (e.g., LDA) | Used under kinetic control to irreversibly deprotonate carbonyl compounds, favoring the formation of the less substituted, kinetic enolate [26] [27]. |

| Copper(I) Triflate | A copper(I) salt precursor used in asymmetric conjugate additions to generate the active catalytic species when combined with a chiral ligand [25]. |

| Trimethylsilyl Chloride (TMSCl) | An additive critical for achieving high reactivity in copper-catalyzed asymmetric conjugate additions, though its precise role can be system-dependent [25]. |

| Alkylzirconium Nucleophiles | Organometallic nucleophiles generated from olefins; used in copper-catalyzed conjugate additions to form new C-C bonds and create tertiary stereocenters [25]. |

Advanced Tools for Stereocontrol: Chiral Auxiliaries, Catalysis, and Emerging Strategies

Within the broader thesis of improving stereoselectivity in asymmetric synthesis research, the use of chiral auxiliaries remains a cornerstone strategy for the efficient construction of enantiomerically pure molecules. These stoichiometric controllers are temporarily incorporated into a substrate to direct the formation of new stereogenic centers with high diastereoselectivity, after which they are removed and potentially recycled. This technical support center focuses on two of the most powerful and widely implemented chiral auxiliaries: Evans' oxazolidinones and Oppolzer's sultam. Their predictable performance and versatility make them indispensable tools for synthetic chemists, particularly in the synthesis of complex natural products and pharmaceutical intermediates where precise stereocontrol is paramount [29] [30]. The following guides and FAQs are designed to help researchers troubleshoot specific issues and optimize their experimental protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key reagents and materials essential for working with these chiral auxiliaries, along with their primary functions.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| n-Butyllithium (n-BuLi) | A strong base used for the deprotonation of oxazolidinones prior to acylation [31] [29]. |

| Lithium Diisopropylamide (LDA) | A strong, non-nucleophilic base for generating enolates from acylated auxiliaries for alkylations and aldol reactions [31] [29]. |

| Dibutylboron Triflate (Bu₂BOTf) | A Lewis acid used with a tertiary amine (e.g., iPr₂NEt) to generate rigid, (Z)-boron enolates for highly diastereoselective Evans aldol reactions [29] [30]. |

| Lithium Borohydride (LiBH₄) | A reducing agent commonly employed for the cleavage and removal of the oxazolidinone auxiliary, converting the imide to a primary alcohol [31] [30]. |

| Carbonyldiimidazole (CDI) | A safe and convenient reagent for the preparation of oxazolidinone rings from chiral amino alcohols, as an alternative to phosgene [31]. |

| (1R)-(+)- and (1S)-(−)-2,10-Camphorsultam | The two enantiomerically pure forms of Oppolzer's sultam, commercially available, allowing access to either product enantiomer [32]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: What are the strategic advantages and disadvantages of using a chiral auxiliary approach compared to catalytic methods?

Answer: The choice between a chiral auxiliary and an asymmetric catalyst is a fundamental strategic decision.

- Advantages:

- High and Predictable Stereocontrol: Chiral auxiliaries often provide exceptionally high and reliable diastereoselectivity (

dr> 95:5) for a wide range of transformations, including alkylations, aldol reactions, and Diels-Alder cyclizations [29] [33]. - Diastereomeric Product Separation: The products of auxiliary-directed reactions are diastereomers, which can be separated by standard techniques like column chromatography or crystallization, ensuring high enantiopurity after auxiliary removal [29].

- Well-Established and Versatile Protocols: The methodologies for Evans' and Oppolzer's auxiliaries are mature, extensively documented, and applicable to many challenging synthetic problems [29] [32].

- High and Predictable Stereocontrol: Chiral auxiliaries often provide exceptionally high and reliable diastereoselectivity (

- Disadvantages:

- Stoichiometric Usage: The auxiliary is used in stoichiometric amounts, which impacts atom economy and can be costly if the auxiliary is expensive or difficult to recover.

- Additional Synthetic Steps: The process requires three extra steps: (1) covalent attachment of the auxiliary to the substrate, (2) the diastereoselective reaction, and (3) cleavage of the auxiliary [29].

FAQ 2: How do I attach the Evans oxazolidinone auxiliary to my carboxylic acid substrate, and what are common pitfalls?

Answer: The standard protocol involves forming the imide by acylating the oxazolidinone with an acyl chloride derivative of your substrate.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Deprotonation: Dissolve the chiral oxazolidinone in an anhydrous solvent like THF or diethyl ether. Cool the solution to -78°C under an inert atmosphere (N₂ or Ar).

- Acylation: Add

n-butyllithium (1.0-1.1 equiv) dropwise. Stir for 15-30 minutes at low temperature. - Quench with Acyl Chloride: Add your acyl chloride (1.1-1.5 equiv) dropwise. Warm the reaction mixture to room temperature slowly and stir until completion (monitored by TLC).

- Work-up: Quench the reaction with a saturated aqueous NH₄Cl solution. Extract with an organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate), wash the combined organic layers with brine, dry (MgSO₄ or Na₂SO₄), and concentrate.

- Purification: Purify the crude product by flash column chromatography [31] [29].

- Troubleshooting Common Pitfalls:

- Low Yield: Ensure all glassware, solvents, and reagents are thoroughly dried. The use of acyl chlorides is generally more efficient than using carboxylic acids directly with coupling agents for this specific acylation.

- Racemization: If your substrate is acid-sensitive or prone to racemization, consider generating the acyl chloride at low temperature and using it immediately.

FAQ 3: My Evans alkylation or aldol reaction is giving poor diastereoselectivity. What could be the cause?

Answer: Poor diastereoselectivity (dr) often stems from issues with enolate geometry or the presence of competing metal cations.

- For Alkylation:

- Cause: The use of a strong base like LDA is crucial to form the specific (Z)-enolate. Weaker or different bases may lead to enolate equilibration or the formation of a mixture of enolate geometries, resulting in poor

dr[29]. - Solution: Confirm the quality and concentration of your base (LDA). Ensure the enolization is performed at the recommended low temperature (e.g., -78°C) and that the reaction vessel is well-agitated during base addition.

- Cause: The use of a strong base like LDA is crucial to form the specific (Z)-enolate. Weaker or different bases may lead to enolate equilibration or the formation of a mixture of enolate geometries, resulting in poor

- For Aldol Reaction:

- Cause 1: The use of lithium enolates instead of boron enolates. Lithium enolates can be less rigid and lead to lower selectivity [30].

- Solution 1: For high

dr, use the standard protocol withBu₂BOTfand a tertiary amine likeiPr₂NEt or Et₃N to form the boron enolate, which provides a well-defined, cyclic transition state [29] [30]. - Cause 2: Contamination of reagents or glassware with moisture or other metal ions.

The following workflow outlines the critical decision points for achieving high stereoselectivity in an Evans aldol reaction:

FAQ 4: What are the best methods for removing the chiral auxiliary without racemizing my product?

Answer: The removal method depends on the auxiliary and the functional group needed in the final product. Cleavage conditions must be chosen to avoid racemization, typically by avoiding strong bases or acids at high temperatures that might enolize the newly formed stereocenter.

- For Evans Oxazolidinones:

- Reductive Cleavage: Treatment with

LiBH₄in THF or Et₂O reduces the imide to a primary alcohol and releases the recovered chiral auxiliary. This is one of the most common methods [31] [30]. - Transesterification: Cleavage can be achieved via nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl, for example, using sodium methoxide in methanol to yield a methyl ester.

- Alternative Transformations: The auxiliary can also be converted directly into other useful groups like aldehydes (via reduction followed by oxidation) or Weinreb amides [29].

- Reductive Cleavage: Treatment with

- For Oppolzer's Sultam:

- Hydrolytic or Reductive Cleavage: Being a sulfonamide, the sultam auxiliary can be removed under relatively mild hydrolytic or reductive conditions, which facilitates its recovery and reuse [32].

FAQ 5: Can chiral auxiliaries be recycled, and is this practical on a large scale?

Answer: Yes, one of the key features of the chiral auxiliary strategy is that the auxiliary can be recovered and reused, mitigating the cost and waste associated with its stoichiometric use.

- Feasibility: Recycling is highly practical, especially for expensive auxiliaries. After cleavage, the auxiliary is often recovered from the reaction mixture and can be purified for subsequent use.

- Advanced Implementation: Research has demonstrated the integration of auxiliary recycling with modern flow chemistry techniques. For example, Oppolzer's sultam has been successfully recovered and reused in a continuous flow system, enabling formal sub-stoichiometric loading of the auxiliary and significantly improving process efficiency [34].

FAQ 6: How does Oppolzer's sultam compare to Evans' oxazolidinone in terms of applicability?

Answer: Both are extremely versatile, but they can have complementary profiles.

- Oppolzer's Sultam: Known for its effectiveness in a wide range of reactions, including Diels-Alder, aldol, ene reactions, Michael additions, and Claisen rearrangements [32]. It is particularly noted as the "chiral auxiliary of choice" for thermal reactions that proceed in the absence of metals [32]. Its rigid, polycyclic structure provides a well-defined chiral environment.

- Evans' Oxazolidinone: The benchmark auxiliary for aldol reactions and α-alkylations. Its performance and stereochemical outcome are exceptionally well-predicted by established transition state models [29] [30].

- Selection Guide: The choice between them may depend on the specific reaction, the required stereochemical outcome, commercial availability, and the ease of introduction and removal for a given substrate.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and applications of these two auxiliaries for easy comparison.

| Feature | Evans' Oxazolidinones | Oppolzer's Sultam (Camphorsultam) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Derived from naturally occurring amino acids or amino alcohols [30]. | Derived from 10-camphorsulfonic acid [30]. |

| Key Reactions | Aldol, Alkylation, Diels-Alder [29]. | Alkylation, Diels-Alder, Aldol, 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition, Michael Addition, Claisen Rearrangement [32]. |

| Enolate for Aldol | Boron enolate (from Bu₂BOTf/amine) for high syn selectivity [29]. | N/A |

| Diastereoselectivity | Typically very high (dr > 95:5) [33]. |

Typically high to very high [32]. |

| Removal Methods | Reductive (e.g., LiBH₄), transesterification, conversion to other functionalities [29]. | Hydrolytic or reductive cleavage [32]. |

| Notable Feature | Well-understood Zimmerman-Traxler transition state model for aldol reactions [29]. | Effective for thermal, metal-free reactions; often used as a "chiral probe" [32]. |

This technical support center addresses common experimental challenges in two cornerstone reactions of asymmetric synthesis: the Sharpless Asymmetric Epoxidation and the Noyori Asymmetric Hydrogenation. These methods are indispensable for constructing enantiomerically enriched molecules in pharmaceutical and fine chemical development. The guidance herein is framed within a broader thesis on systematically improving stereoselectivity, focusing on practical problem-solving for research scientists.

Sharpless Asymmetric Epoxidation (SAE) Support

The Sharpless Epoxidation enables highly enantioselective epoxidation of prochiral allylic alcohols. The reaction uses tert-butyl hydroperoxide as the oxidant and is catalyzed by Ti(OiPr)4 in the presence of an enantiomerically enriched tartrate derivative as the chiral ligand [35]. The mechanism involves a putative transition state where the titanium center binds simultaneously to the hydroperoxide, the allylic alcohol, and the tartrate ligand, creating a chiral environment that dictates the face-selective epoxidation of the alkene [35].

Troubleshooting Guide for SAE

Table 1: Common Issues and Solutions in Sharpless Epoxidation

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Enantioselectivity | - Moisture/air sensitivity deactivating catalyst- Incorrect tartrate enantiomer ratio or purity- Impurities in allylic alcohol substrate- Incorrect reaction temperature | - Ensure strict anhydrous conditions using molecular sieves [36]- Use high-purity DET (-) or DET (+)- Purify allylic alcohol substrate before use- Maintain consistent, recommended temperature [37] |

| Slow Reaction Rate | - Low catalyst loading or activity- Inefficient oxidant- Substrate steric hindrance | - Use catalytic Ti(OiPr)₄ with molecular sieves [36]- Ensure fresh, high-quality tert-butyl hydroperoxide- Optimize reaction time and temperature |

| Low Yield of Epoxide | - Decomposition of epoxide product under reaction conditions- Side reactions- Incomplete conversion | - Monitor reaction progress closely (TLC/GC)- Avoid excessive reaction times- Quench reaction promptly after completion |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for SAE

Q1: How can I make the SAE reaction catalytic in titanium and why are molecular sieves critical for this?

- The original SAE used stoichiometric amounts of titanium tartrate. A major improvement uses 3-10 mol% Ti(OiPr)₄ and an equivalent of tartrate ligand with activated 4Å molecular sieves [36]. The sieves bind water, preventing hydrolysis and deactivation of the titanium catalyst, allowing for catalytic use.

Q2: What is the most common mistake leading to low enantiomeric excess (ee) in SAE?

- The most prevalent error is inadequate exclusion of moisture. Titanium catalysts are highly moisture-sensitive. Strict anhydrous conditions are non-negotiable for high ee. This includes drying all glassware, using anhydrous solvents, and employing molecular sieves [37].

Q3: Can SAE be applied to all allylic alcohols?

- SAE works excellently for primary and secondary allylic alcohols. The free OH group is essential for coordinating to the titanium center and orienting the substrate in the chiral pocket. The reaction is generally not applicable to tertiary allylic alcohols or simple alkenes without the alcohol directing group.

Experimental Protocol: Standard Catalytic SAE

Reaction: Epoxidation of (E)-2-Hexen-1-ol to (2R,3R)-(-)-3-Propyloxiranemethanol [35] [36].

Required Materials:

- Ti(OiPr)₄ (5-10 mol%)

- L-(-)- or D-(+)-Diethyl tartrate (DET, 6-12 mol%)

- anhydrous CH₂Cl₂

- Activated 4Å molecular sieves (powder)

- tert-Butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP, ~5.0 M in decane or nonane)

- Allylic alcohol substrate (e.g., (E)-2-Hexen-1-ol)

Procedure:

- Setup: Flame-dry a round-bottom flask under argon and cool under an inert atmosphere.

- Catalyst Formation: Charge the flask with activated 4Å molecular sieves (~100 mg/mmol substrate). Add anhydrous CH₂Cl₂. Stir and sequentially add Ti(OiPr)₄ (0.1 equiv) and D-(-)-DET (0.12 equiv). Stir the mixture for 30 minutes at room temperature to form the chiral titanium-tartrate complex.

- Reaction: Cool the reaction mixture to -20°C. Add the allylic alcohol substrate (1.0 equiv), followed by dropwise addition of TBHP (1.2-1.5 equiv). Continue stirring at -20°C, monitoring by TLC.

- Work-up: After completion (typically 6-24 hours), quench the reaction by adding a saturated aqueous solution of sodium sulfite (Na₂SO₃). Stir for 1 hour to decompose excess peroxide.

- Extraction: Extract the aqueous mixture with ethyl acetate (3x). Combine the organic layers, wash with brine, and dry over anhydrous MgSO₄.

- Purification: Filter, concentrate under reduced pressure, and purify the crude product by flash column chromatography.

Research Reagent Solutions for SAE

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Sharpless Epoxidation

| Reagent | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Ti(OiPr)₄ (Titanium(IV) isopropoxide) | Lewis acid catalyst core | Highly moisture-sensitive; must be handled under inert atmosphere. |

| DET (Diethyl Tartrate) | Chiral ligand | Determines absolute stereochemistry of the epoxide; use D-(-)-DET for (2S,3S) and L-(+)-DET for (2R,3R) in allylic alcohols. |

| t-BuOOH (tert-Butyl hydroperoxide) | Terminal oxidant | Use nonaqueous solution (e.g., in decane); aqueous solutions can deactivate the catalyst. |

| Molecular Sieves (4Å) | Water scavenger | Essential for catalytic version; must be activated (dried) prior to use. |

| anhydrous CH₂Cl₂ | Solvent | Low polarity favors the closed transition state; must be rigorously dried. |

SAE Workflow Diagram

Noyori Asymmetric Hydrogenation Support

Noyori Asymmetric Hydrogenation represents a pinnacle of efficiency in enantioselective reduction. It employs chiral BINAP-Ru(II) complexes (e.g., RuCl₂[(S)-BINAP][(S)-DAIPEN]) to hydrogenate functionalized ketones and alkenes with exceptional enantioselectivity, often exceeding 99% ee [36]. The mechanism for ketone hydrogenation involves a unique metal-ligand cooperative process, where the chiral BINAP ligand controls the stereochemistry and a hydride on the ruthenium center, combined with a proton from an amine ligand (like DPEN), delivers H₂ across the C=O bond via a six-membered pericyclic transition state.

Troubleshooting Guide for Noyori Hydrogenation

Table 3: Common Issues and Solutions in Noyori Hydrogenation

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Enantioselectivity | - Incorrect catalyst selection for substrate- Catalyst decomposition or impurity- Solvent effects- Hydrogen pressure too high/low | - Use Ru-BINAP-DPEN for ketones; Ru-BINAP for alkenes [38]- Use fresh, high-purity catalyst- Optimize solvent (e.g., iPrOH, toluene)- Screen H₂ pressure (typically 5-100 bar) |

| No/Slow Conversion | - Catalyst poisoning (impurities)- Inadequate H₂ gas mixing- Low temperature or catalyst loading | - Scrupulously purify substrate- Ensure efficient stirring for H₂ uptake- Increase temperature or catalyst loading slightly |

| Over-reduction or Side Products | - Excessive reaction time- Too high H₂ pressure or temperature- Substrate instability | - Monitor reaction progress carefully- Optimize pressure/temperature profile- Consider protective groups for sensitive functionalities |