Novel Catalysts for C-H Activation: Mechanistic Insights, Sustainable Applications, and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of C-H activation, with a focus on novel catalyst development and reaction mechanisms.

Novel Catalysts for C-H Activation: Mechanistic Insights, Sustainable Applications, and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of C-H activation, with a focus on novel catalyst development and reaction mechanisms. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores foundational mechanistic principles—from oxidative addition to the modern continuum model—and highlights the pivotal shift toward sustainable 3d metal catalysts like Fe, Co, and Mn. The scope extends to advanced methodological applications, including high-throughput experimentation for drug discovery and late-stage functionalization of complex molecules. It further offers practical guidance on troubleshooting catalytic systems and compares the performance of precious versus earth-abundant metals. By synthesizing insights across these four core intents, this resource aims to equip practitioners with the knowledge to design more efficient, selective, and sustainable C-H functionalization strategies for biomedical and industrial applications.

Deconstructing C-H Activation: From Classical Mechanisms to a Modern Reactivity Continuum

In the field of synthetic chemistry, the terms C-H activation and C-H functionalization are often used interchangeably, creating ambiguity for researchers and industry professionals. However, a precise distinction exists, rooted in the reaction mechanism, which is crucial for designing and developing novel catalysts. This guide provides a technical clarification of these terms, framed within contemporary research on advanced catalytic systems.

Core Definitions: A Mechanistic Distinction

The fundamental difference lies in the involvement of an organometallic intermediate where a carbon-metal bond is formed directly from the cleavage of a C-H bond.

- C-H Activation (Strict Sense): This term refers specifically to a reaction mechanism where a C-H bond interacts directly with a transition metal center, resulting in bond cleavage and the formation of a new organometallic species (M–C bond) [1]. The metal is intimately involved in the bond-breaking event.

- C-H Functionalization (Broad Sense): This is a more general term describing any reaction that converts a C-H bond into a C-X bond (where X ≠ H), such as C–C, C–O, or C–N bonds [1]. It is agnostic to the mechanism and encompasses all reactions that fall under the strict definition of C-H activation, plus other pathways that do not proceed through a direct metal-carbon bond-forming step.

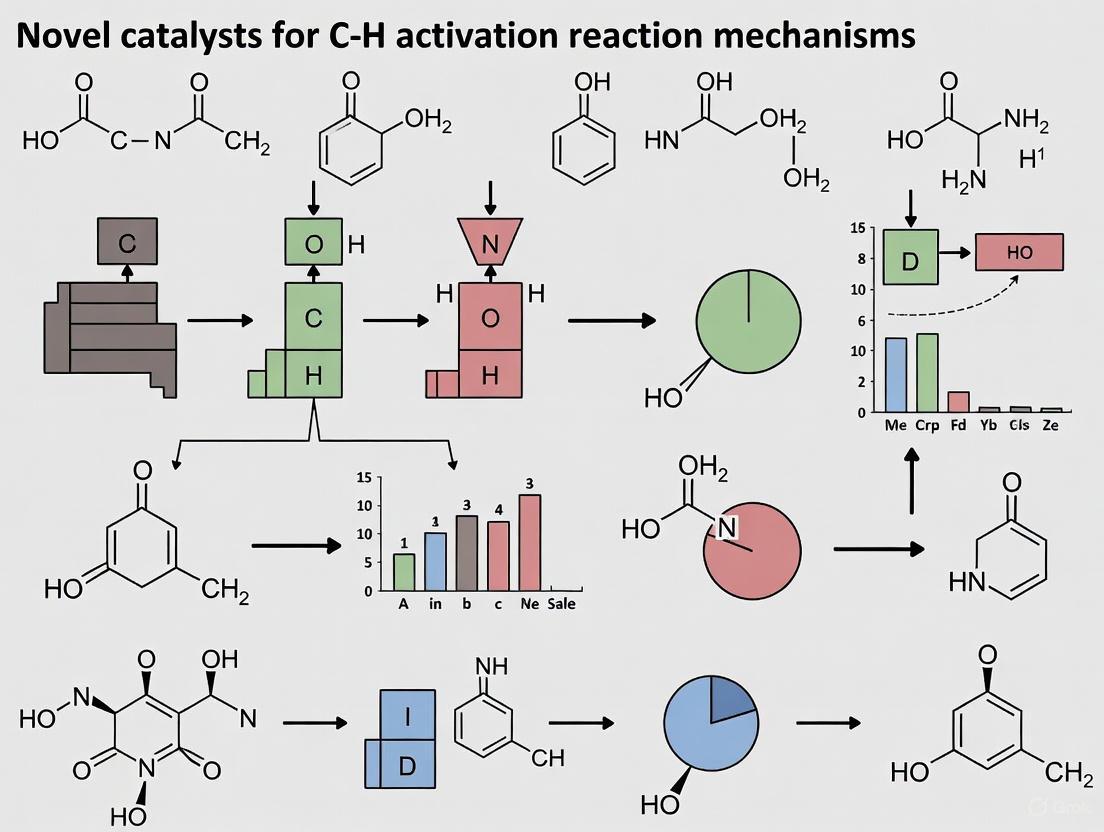

The diagram below illustrates the core mechanistic distinction between these two pathways.

Mechanistic Pathways in C–H Activation

Within the strict definition of C–H activation, three primary mechanisms are recognized, classified by how the metal cleaves the C–H bond [1]. Understanding these is essential for catalyst design.

- 1. Oxidative Addition: A low-valent, electron-rich metal center inserts into the C–H bond, cleaving it and increasing its oxidation state by two units. This is common for metals like Pd(0) [1].

- 2. Electrophilic Activation: An electrophilic metal center (e.g., Pd(II)) attacks the electron density of the C–H bond, displacing a proton. A key variant is Concerted Metalation-Deprotonation (CMD), where a ligand on the metal (often a carboxylate) acts as an internal base to accept the proton simultaneously [1].

- 3. σ-Bond Metathesis: This concerted mechanism proceeds through a four-membered transition state where bonds break and form in a single step without a change in the metal's oxidation state. It is favored for high-valent, electron-poor early transition metals [1].

Quantitative Comparison of C–H Activation Mechanisms

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these core mechanistic pathways.

| Mechanism | Metal Oxidation State Change | Key Characteristic | Typical Catalysts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative Addition | Increases by 2 | Favored by electron-rich, low-valent metal centers | Pd(0), Rh(I), Ir(I) [1] |

| Electrophilic Activation | No change | Involves electrophilic attack on the C–H bond; includes CMD | Pd(II), Pt(II), Au(III) [1] |

| σ-Bond Metathesis | No change | Concerted process via a 4-membered transition state | High-valent early transition metals, Ln complexes [1] |

Contemporary Research and Experimental Protocols

Recent advances in catalyst development highlight the practical implications of these definitions. The following examples showcase modern C–H activation methodologies.

Electrochemical Palladium-Catalyzed C–H Arylation

A 2025 study by Baroliya et al. demonstrates a novel directed C–H activation protocol for the ortho-arylation of 2-phenylpyridine, using electricity as a green oxidant [2].

Experimental Protocol:

- Reaction Setup: An undivided electrochemical cell was used.

- Conditions: 2-phenylpyridine (1.0 equiv), arenediazonium tetrafluoroborate salt (1.2 equiv), Pd(OAc)₂ (10 mol%), K₂HPO₄ (base), and nBu₄NF (additive) in solvent.

- Execution: The reaction was conducted under constant current (specific value optimized, e.g., 5 mA) at room temperature for several hours.

- Key Finding: The reaction failed in the absence of electrical current, proving its dual role in regenerating the Pd(II) catalyst and reducing the diazonium salt [2].

Mechanistic Insight: The mechanism proceeds through a well-defined organometallic intermediate. The pyridine nitrogen directs the palladium catalyst to the ortho C–H bond, forming a cyclopalladated species. This intermediate then reacts with the arylation partner, and electricity drives the catalytic cycle by re-oxidizing Pd(0) to Pd(II) [2].

Iron-Catalyzed Undirected C–H Functionalization

A 2025 report describes an iron catalyst that functionalizes strong aliphatic C–H bonds in alkanes to form C–C bonds with 1,4-quinones [3]. This is a prime example of C–H functionalization that likely does not proceed via classical C–H activation.

Experimental Protocol:

- Reaction Setup: A flask charged with the alkane (2.0 equiv), 1,4-quinone (1.0 equiv), Fe catalyst (e.g., Fe(acac)₃), and a bioinspired thiolate ligand (BCMOM).

- Conditions: The reaction uses H₂O₂ as an oxidant in a CH₃CN/H₂O solvent mixture at room temperature.

- Analysis: High-resolution mass spectrometry confirmed the formation of a high-valent iron-oxo species, [(acac)₂(BCMOM)₂•+FeIV(O)], as the active oxidant [3].

Mechanistic Insight: The mechanism involves Hydrogen Atom Transfer (HAT). The iron-oxo species abstracts a hydrogen atom from the alkane, generating an alkyl radical and an Fe(IV)-OH species. The alkyl radical then "escapes" the metal's coordination sphere and adds to the quinone, forming the new C–C bond. This HAT pathway, which suppresses an oxygen-rebound step, is distinct from mechanisms forming an Fe–C bond [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for C–H Activation Research

The table below details key reagents and their functions in developing novel C–H activation protocols, as exemplified in recent literature.

| Reagent Category | Example(s) | Function in Reaction |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Catalysts | Pd(OAc)₂, [RhCpCl₂]₂, CpCo(CO)I₂ | Central catalyst for C–H bond cleavage and formation of organometallic intermediates [2] [4] [5]. |

| Oxidants | Cu(OAc)₂, AgOAc, Ag₂CO₃, Benzoquinone, O₂/air, Electricity | Re-oxidize the transition metal to its active state in catalytic cycles, especially for Pd(0)/Pd(II) and Pd(II)/Pd(IV) cycles [2] [4]. |

| Directing Groups (DG) | Pyridine, Anilides, Amides | Coordinate to the metal catalyst, bringing it into proximity with a specific C–H bond to control regioselectivity [2] [1]. |

| Additives / Bases | Carboxylates (e.g., pivalate, acetate), K₂HPO₄, CsOAc | Act as bases for deprotonation in CMD mechanisms; neutralize acid byproducts [2] [4]. |

| Halide Scavengers | AgSbF₆, AgOTf | Abstract halide ligands from metal precursors to generate more reactive cationic metal species [4]. |

For researchers working on novel catalysts, the distinction between C–H activation and C–H functionalization is more than semantic. It is a mechanistic blueprint. "C–H activation" explicitly demands a pathway where the catalyst forms an organometallic intermediate via direct C–H bond cleavage. In contrast, "C–H functionalization" is an umbrella term for the overall synthetic transformation. Precision in this language is critical for accurately describing catalytic mechanisms, designing next-generation catalysts—such as the heterogeneous palladium systems that address toxicity in pharmaceutical production or the earth-abundant iron catalysts that mimic enzymatic reactivity—and driving innovation in sustainable synthetic methodology [6] [3].

Transition metal-catalyzed C–H activation represents a cornerstone of modern synthetic methodology, enabling the direct functionalization of inert carbon-hydrogen bonds. This approach offers a more atom-economical and sustainable pathway for constructing complex molecular architectures compared to traditional cross-coupling that requires pre-functionalized starting materials. For researchers developing novel catalysts, a deep understanding of the fundamental mechanistic pathways is paramount. This guide provides an in-depth examination of three classical mechanisms—oxidative addition, σ-bond metathesis, and electrophilic substitution—framed within the context of contemporary catalyst design for C–H activation. The discussion is supported by quantitative data, experimental protocols, and visualization of key concepts to serve the needs of scientists working in catalysis, synthetic chemistry, and pharmaceutical development.

Core Mechanistic Pathways

Oxidative Addition

Fundamental Principles: Oxidative addition (OA) typically occurs with electron-rich, low-valent metal complexes (often late transition metals). During the reaction, a substrate X–Y adds to the metal center (M), resulting in the cleavage of the X–Y bond and the formation of two new M–X and M–Y bonds. This process increases both the coordination number and the oxidation state of the metal by two units [7]. A defining characteristic of this pathway is that the metal center provides two electrons to cleave the X–Y bond [8].

Catalyst Design Context: The requirement for a metal center to undergo a formal two-electron oxidation can present a significant energy barrier. Innovative catalyst designs aim to mitigate this. For instance, recent research on artful single-atom catalysts (ASACs) demonstrates how anchoring Pd single atoms on specific facets of reducible supports like CeO₂(110) can bypass the traditional oxidative addition prerequisite. In these systems, the support acts as an electron reservoir, enabling the oxidative addition of challenging substrates like aryl chlorides without requiring a bivalent change in the Pd oxidation state, thus achieving remarkable turnover numbers (TONs up to 45,327,037) [9].

Key Mechanistic Variations: Oxidative addition can proceed via three primary pathways, each with distinct implications for catalyst design and stereochemical outcome [7]:

- Concerted Mechanism: The substrate (e.g., H₂ or an alkane) binds initially as a σ-complex, followed by bond cleavage facilitated by back-donation from the metal. This pathway proceeds through a three-membered ring transition state and typically results in cis addition of the ligands [7] [8].

- S_N2 Mechanism: The metal acts as a nucleophile, attacking the σ* orbital of the alkyl halide substrate at the least electronegative atom. This mechanism is more prevalent with nucleophilic metals and follows the reactivity order Alkyl > Aryl > Alkene for halides [7].

- Radical Mechanism: This can involve metal-centered radicals abstracting atoms from halides, sometimes initiated photochemically. Changes in substrate, metal complex, or reagent impurities can influence the rate and favor this pathway [7].

Table 1: Comparative Energetics for Methane C–H Activation via Oxidative Addition

| Metal Complex | Ground State | σ-Bond Complex ΔE (kcal/mol) | Activation Barrier ΔE‡ (kcal/mol) | Reaction Energy ΔE (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Cp*)(PMe₃)Ir (1-IrP) | Triplet (ΔEₛₜ = 3.6) | -13.1 | 0.10 | -28.8 |

| (Cp*)(CO)Ir (1-IrC) | Triplet (ΔEₛₜ = 1.0) | -13.7 | 1.3 | -21.0 |

Data sourced from density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the B3LYP-D3/def2-SVP level, using methane as the substrate [8].

σ-Bond Metathesis

Fundamental Principles: The σ-bond metathesis mechanism is characteristic of early transition metals and f-block elements (e.g., Ta⁺) that are often electron-deficient and lack accessible electrons for oxidative addition [8] [10]. This pathway preserves the oxidation state of the metal throughout the reaction [8]. It proceeds through a four-membered cyclic transition state where the incoming C–H bond and the outgoing M–R' bond are simultaneously broken and formed [8].

Catalyst Design Context: This mechanism is vital for activating C–H bonds using metals that are resistant to redox changes. Recent studies on Ta⁺-mediated methane activation reveal complex sequential chemistry, including a "ring-opening σ-bond metathesis" where an unbroken metallacycle bond acts as a tether, preventing product separation and allowing further isomerization and dehydrogenation [10]. This demonstrates how rigid ligand architectures can enforce unique reaction coordinates in catalyst design.

Electron Flow Analysis: Advanced computational analyses, such as Intrinsic Bond Orbital (IBO) analysis, reveal that in σ-bond metathesis, the electron pair accepting the proton in the C–H bond cleavage originates from the metal-ligand σ-bonds, distinct from the d-orbital electron pairs used in oxidative addition [8].

Electrophilic Substitution

Fundamental Principles: Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution (EAS) is a fundamental two-step mechanism for functionalizing aromatic rings [11]. An electrophile (E⁺) attacks the aromatic π-system, forming a resonance-stabilized carbocation intermediate (arenium ion). This slow, rate-determining step disrupts aromaticity. A base then deprotonates this intermediate, restoring aromaticity and yielding the substituted product [11].

Catalyst Design Context: In transition metal-mediated C–H activation, electrophilic activation involves an electropositive metal center that withdraws electron density from the C–H bond, enhancing the acidity of the hydrogen atom and facilitating its abstraction by a base [8]. The reaction can proceed via a four- or six-membered transition state. The electron pair for proton acceptance comes from ligand lone pairs, not the metal center itself [8]. This mechanism is exploited in directed C–H activation, where a coordinating directing group (e.g., pyridine in 2-phenylpyridine) positions the catalyst for site-selective functionalization [2].

Directing Group Effects: The nature of substituents on the aromatic ring critically influences EAS. They are classified as:

- Ortho-/Para-Directing Activators: Electron-donating groups (e.g., -CH₃) increase the ring's electron density, stabilizing the arenium ion intermediate and lowering the activation barrier for ortho/para attack [11].

- Meta-Directing Deactivators: Electron-withdrawing groups (e.g., -NO₂) reduce the ring's electron density, making it less nucleophilic. The meta-position is often least deactivated [11]. A notable exception is halogens, which are deactivating yet ortho-/para-directing due to their resonance electron-donating ability [11].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Palladium-Catalyzed Electrochemical C–H Arylation

This protocol details the ortho-arylation of 2-phenylpyridine, showcasing a modern approach that uses electricity as a clean oxidant, aligning with sustainable chemistry goals [2].

- Reaction Setup: Conduct reactions in an undivided electrochemical cell equipped with a stir bar. The specific electrode materials are critical for optimal yield [2].

- Procedure:

- Charge the cell with 2-phenylpyridine (0.2 mmol), arenediazonium tetrafluoroborate salt (0.3 mmol), Pd(OAc)₂ (10 mol%), K₂HPO₄ (1.0 equiv), and nBu₄NF (1.0 equiv).

- Add anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF, 2.0 mL) as the solvent under an inert atmosphere.

- Apply a constant current (specific value optimized by the source, typically ~3-5 mA). Both higher and lower currents reduce yield.

- Monitor the reaction by TLC. Upon completion, quench with water and extract with ethyl acetate.

- Purify the crude product by flash column chromatography to isolate the mono-arylated product.

- Key Notes: The reaction proceeds under mild conditions. The electricity serves a dual role: it reoxidizes Pd(0) to Pd(II) to close the catalytic cycle and can also reduce the arenediazonium ion. The reaction exhibits excellent functional group tolerance [2].

Protocol: Differentiating C–H Activation Mechanisms via IBO Analysis

This methodology uses computational analysis to visually distinguish between different C–H activation mechanisms, a powerful tool for mechanistic verification in novel catalyst research [8].

- Computational Details:

- Geometry Optimization and Frequency Calculation: Perform all calculations using Gaussian 16 at the B3LYP-D3/def2-SVP level of theory. Confirm transition states by the presence of a single imaginary frequency.

- Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC): Run IRC calculations for approximately 200 points along the reaction pathway at the same level of theory to model the progression from reactants to products.

- Single-Point Recalculation: Use the ORCA package to perform single-point calculations for each IRC point.

- Orbital Localization and Tracking: Generate localized orbitals for each point using the Intrinsic Bond Orbital (IBO) scheme via IboView software. Track the evolution of these orbitals along the IRC path.

- Data Interpretation: The key differentiator is the source of the electron pair that accepts the proton from the cleaved C–H bond [8]:

- Oxidative Addition: Electron pair comes from metal d-orbitals.

- σ-Bond Metathesis: Electron pair comes from metal-ligand σ-bonds.

- Electrophilic Activation: Electron pair comes from lone pairs on ligands.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for C–H Activation Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Palladium Acetate (Pd(OAc)₂) | Versatile catalyst precursor for Pd(II)/Pd(0) catalytic cycles. | Electrochemical C–H arylation of 2-phenylpyridines [2]. |

| Artful Single-Atom Catalysts (ASACs) | Heterogeneous catalysts with adaptive coordination, bypassing traditional OA. | Suzuki coupling of aryl chlorides and challenging heterocycles [9]. |

| Arenediazonium Tetrafluoroborate Salts | Electrophilic arylating agents; more reactive than aryl halides. | Serve as coupling partners in electrochemical C–H arylation [2]. |

| Tetramethylthiourea (TMTU) | Ligand/additive to promote efficiency of C–H activation steps. | Facilitates monomeric palladacycle formation in benzimidazole synthesis [12]. |

| Cerium Dioxide (CeO₂) Supports | Reducible oxide support for SACs; acts as an electron reservoir. | Key component in Pd1-CeO₂(110) ASACs for electron modulation [9]. |

| Copper Salts (e.g., Cu(OAc)₂) | Stoichiometric oxidants to regenerate active Pd(II) species. | Used in Pd-catalyzed C–H functionalization/C–N bond formation [12]. |

| Directed Substrates (e.g., 2-Phenylpyridine) | Model substrates where a heteroatom directs metal for ortho C–H activation. | Standard substrate for studying regioselective palladium-catalyzed C–H functionalization [2]. |

Visualizing Mechanistic Pathways and Workflows

Electron Flow in C–H Activation Mechanisms

Diagram 1: Electron flow paths differentiate C–H activation mechanisms. The source of the electron pair that accepts the proton is a key diagnostic feature [8].

Experimental Workflow for Mechanistic Study

Diagram 2: Computational workflow for differentiating C–H activation mechanisms using Intrinsic Bond Orbital (IBO) analysis [8].

The classical pathways of oxidative addition, σ-bond metathesis, and electrophilic substitution provide the fundamental framework for understanding and innovating in the field of C–H activation. For the researcher designing novel catalysts, the insights are clear: the choice of metal center, its oxidation state, and the supporting ligand/support environment directly dictate the accessible mechanisms. Modern advancements, such as single-atom catalysts on engineered supports and electrochemical methods, are pushing the boundaries of these classical pathways. They enable reactions under milder conditions, with improved selectivity, and using less reactive substrates. A deep, mechanistic understanding, supported by both experimental and advanced computational protocols, remains the key to driving progress in the sustainable synthesis of complex molecules for pharmaceutical and materials science applications.

The Concerted Metalation Deprotonation (CMD) Mechanism and its Role

Concerted Metalation-Deprotonation (CMD) is a fundamental mechanistic pathway in transition-metal-catalyzed C–H functionalization. In this process, cleavage of the inert carbon-hydrogen bond and formation of a new carbon-metal bond occur simultaneously through a single, concerted transition state, without proceeding through a discrete metal hydride intermediate [13]. The CMD mechanism was first proposed by Winstein and Traylor in 1955 during mechanistic studies of organomercury compounds and has since been recognized as a widespread pathway, particularly for high-valent, late transition metals like Pd(II), Rh(III), Ir(III), and Ru(II) [13]. This mechanism represents a significant advancement in C–H activation research because it offers a kinetically favorable alternative to traditional pathways like oxidative addition and explains the critical role of carboxylate bases in facilitating these transformations across a broad spectrum of aromatic substrates [13] [14].

The importance of CMD extends to modern catalyst design, providing a conceptual framework for developing novel catalytic systems that operate with higher efficiency and selectivity. For drug development professionals, understanding CMD is crucial as it enables more direct synthetic routes to complex molecules through selective C–H functionalization, minimizing synthetic steps and reducing waste production [15].

Core Mechanism and Historical Development

Fundamental Steps of the CMD Pathway

The CMD mechanism involves a coordinated sequence where a carboxylate or carbonate base deprotonates the substrate while the metal center forms a new organometallic bond. The process can be broken down into several key stages [13]:

- Pre-coordination: The substrate coordinates to the metal center, often through a directing group, positioning the target C–H bond in proximity to the metal.

- Concerted Transition State: The system reaches a transition state where partial cleavage of the C–H bond and partial formation of the C–Metal bond occur simultaneously. The carboxylate base accepts the proton while the metal-carbon bond forms.

- Product Formation: The metalated intermediate is formed, accompanied by release of the carboxylic acid. This intermediate can then undergo subsequent functionalization steps.

A distinctive feature of the CMD transition state is the simultaneous breaking and forming of multiple bonds. The anionic metal-carboxylate bond weakens as the carbon-hydrogen bond breaks, while the carbon-metal bond forms and the oxygen-hydrogen bond of the carboxylic acid is created [13]. This concerted process often presents a lower energy pathway compared to alternatives like oxidative addition, particularly for electron-rich metal centers [13].

Historical Context and Key Discoveries

The development of the CMD concept spans several decades, with critical insights emerging from both experimental and computational studies:

Table: Historical Development of the CMD Mechanism

| Year | Researchers | Key Contribution | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1955 | Winstein & Traylor [13] | First proposed CMD-like pathway | Initial mechanism for acetolysis of organomercury compounds |

| 1968 | Davidson & Triggs [13] | Extended metalation from Hg to Pd | Established organopalladium intermediates in benzene coupling |

| 2008 | Gorelsky, Lapointe, & Fagnou [13] [14] | Computational analysis across diverse arenes | Demonstrated CMD predictability for regioselectivity and reactivity |

| 2021 | Modern Techniques [13] | Picosecond-millisecond IR spectroscopy | Direct observation of proton transfer states |

| 2023 | Bouley et al. [16] | C–H activation at Pd(III) centers | Expanded CMD relevance to higher oxidation states |

The historical trajectory of CMD research demonstrates how initial mechanistic proposals have evolved into a well-understood framework with broad predictive capability. Early work established the fundamental concept, while contemporary studies continue to reveal new dimensions of this mechanism, including its applicability to previously unexplored metal oxidation states and substrate classes [13] [16].

Recent Advances and Research Applications

CMD in 3d Transition Metal Catalysis

The application of CMD mechanisms to earth-abundant 3d transition metals represents a significant advancement in sustainable catalysis. While precious metals like palladium have dominated C–H functionalization, recent research has successfully implemented CMD pathways with nickel, copper, iron, and cobalt catalysts [15]. These metals offer advantages in cost and abundance but present different electronic properties and mechanistic complexities compared to their precious metal counterparts.

Nickel catalysis has emerged as particularly promising, with Chatani and You demonstrating simultaneous breakthroughs in 2014 for the β-C(sp³)–H arylation of aliphatic amides using nickel(II) catalysts [15]. These systems utilized 8-aminoquinoline as a directing group and carboxylate additives, with mechanistic studies supporting a Ni(II)/Ni(IV) catalytic cycle where C–H cleavage occurs via CMD [15]. The expansion of CMD to 3d metals requires careful tuning of reaction parameters, as these metals often have different coordination preferences and redox properties compared to traditional precious metal catalysts.

Extension to High-Valent Palladium Chemistry

Recent research has expanded the understanding of CMD beyond the traditional Pd(II) systems to include higher oxidation states. In 2023, Bouley et al. provided the first direct observation of C–H activation via CMD at an isolated mononuclear Pd(III) center [16]. This study demonstrated that oxidation of the Pd(II) complex (MeN4)Pd(II)(neophyl)Cl with ferrocenium hexafluorophosphate yielded a stable Pd(III) species that underwent acetate-promoted Csp²–H bond activation to form a cyclometalated product [16].

This finding is mechanistically significant because it demonstrates that CMD is not limited to Pd(II) chemistry but can operate across multiple oxidation states. The study employed comprehensive characterization techniques including EPR and UV-Vis spectroscopy to monitor the C–H activation process directly, providing kinetic and spectroscopic evidence for CMD at this uncommon oxidation state [16]. The flexibility of the pyridinophane ligand structure was identified as a key factor in enabling this transformation, highlighting the importance of ligand design in accessing new CMD pathways [16].

Electrophilic CMD (eCMD) and Selectivity Control

Further refinement of the CMD model has led to the recognition of distinct subclasses based on transition state polarization. Brad P. Carrow introduced the concept of Electrophilic CMD (eCMD) to describe complexes where the transition state features a build-up of partial positive charge on the ipso carbon [13]. This contrasts with Fagnou's "standard" CMD model, which involves intermediate levels of negative charge build-up on the ipso carbon [13].

The differentiation between CMD and eCMD has important implications for predicting site selectivity in catalytic reactions. The eCMD pathway is characterized by metal-carbon bonding that is more advanced than carbon-hydrogen cleavage relative to the standard CMD transition state, resulting in electrophilic reactivity patterns that favor more π-basic substrates or sites [13]. This conceptual framework helps explain how minor changes in catalyst structure can lead to significant differences in selectivity, enabling more rational catalyst design for specific transformation requirements.

Experimental Analysis of CMD Mechanisms

Key Methodologies and Diagnostic Tools

Several experimental techniques provide critical insights for establishing CMD mechanisms in catalytic systems:

- Deuterium-Labeling Experiments: These studies test the reversibility of C–H bond cleavage. Chatani et al. observed H/D exchange in both products and recovered starting materials, indicating reversible C–H cleavage preceding the functionalization step [15].

- Kinetic Isotope Effect (KIE) Measurements: KIE values provide information about the rate-determining step. In CMD processes, KIEs can help distinguish between pre-association steps and the C–H cleavage event itself [16].

- Stoichiometric Studies: Reactions with isolated metal complexes, such as the Pd(III) system studied by Bouley et al., allow direct observation of C–H activation steps without interference from other catalytic cycle steps [16].

- Computational Analysis: Density functional theory (DFT) calculations model transition state geometries and energies, providing theoretical support for concerted pathways [13] [15] [16].

The experimental workflow for mechanistic investigation typically begins with kinetic studies and isotopic labeling, progresses to isolation and characterization of proposed intermediates, and culminates in computational validation of the proposed pathway.

Representative Experimental Protocol

The following detailed methodology is adapted from mechanistic studies on nickel-catalyzed C–H arylation via CMD [15]:

Objective: To investigate the CMD mechanism in Ni-catalyzed β-C(sp³)–H arylation of 8-aminoquinoline amides.

Reaction Setup:

- In a nitrogen-filled glovebox, combine Ni(OTf)₂ (0.05 mmol, 10 mol%), sterically bulky carboxylic acid additive (e.g., 2,4,6-trimethylbenzoic acid, 0.2 mmol, 40 mol%), and Na₂CO₃ (0.75 mmol, 1.5 equiv) in a screw-cap reaction vial.

- Add substrate (8-aminoquinoline amide, 0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and aryl iodide (0.75 mmol, 1.5 equiv) to the vial.

- Add anhydrous DMF (2.0 mL) as solvent and seal the vial with a Teflon-lined cap.

- Remove from glovebox and heat at 140°C with stirring for 24 hours.

Deuterium-Labeling Experiments:

- Prepare substrate with deuterium at the proposed cleavage site.

- Set up parallel reactions with deuterated and non-deuterated substrates under standard conditions.

- Monitor H/D exchange by ¹H NMR spectroscopy or mass spectrometry of both products and recovered starting materials.

- Compare reaction rates between deuterated and non-deuterated substrates to calculate kinetic isotope effects.

Control Experiments:

- Carry out reaction in the presence of radical scavengers like TEMPO to exclude radical pathways.

- Systematically vary carboxylate additives to assess impact on reaction efficiency.

- Attempt isolation and characterization of proposed cyclometalated intermediates.

Data Analysis:

- Monitor reaction progress by TLC or GC-MS.

- Isolate products by flash chromatography and characterize by NMR, HRMS.

- Quantify H/D exchange by integration of relevant signals in ¹H NMR spectra.

- Calculate first-order rate constants for deuterated and non-deuterated substrates to determine KIE values.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CMD Studies

| Reagent/Catalyst | Function in CMD Mechanism | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Catalysts | Metal center for C–H activation | Pd(OAc)₂, Ni(OTf)₂, [(η²-C₂H₄)₂Rh(μ-OAc)]₂ [13] [15] [17] |

| Carboxylate Bases/Additives | Deprotonation agent in CMD transition state | Pivalic acid, 2,4,6-trimethylbenzoic acid, acetate, benzoate [13] [15] |

| Directing Groups | Substrate coordination to metal center | 8-Aminoqunoline (8-AQ), pyridinophane ligands [15] [16] |

| Oxidants | Regeneration of active catalyst species | Cu(OPiv)₂, AgOAc [16] [17] |

| Deuterated Solvents/Substrates | Mechanistic probes for H/D exchange | Deuterated analogs of substrates, CD₃CN, DMSO-d₆ [15] [16] |

Implications for Novel Catalyst Design

Mechanistic Insights Guiding Catalyst Development

Understanding the CMD mechanism provides fundamental principles for designing novel catalysts with enhanced activity and selectivity:

- Carboxylate Optimization: The identity of the carboxylate base significantly influences reaction rates and selectivity in CMD processes. Sterically hindered carboxylates like pivalate often improve efficiency by facilitating proton transfer while minimizing unwanted coordination [13] [15].

- Ligand Design for 3d Metals: For earth-abundant 3d metals, ligand architecture must accommodate different coordination geometries and electronic requirements compared to precious metals. The successful implementation of CMD with nickel, cobalt, and iron catalysts requires ligands that stabilize the appropriate oxidation states and facilitate the concerted transition state [15].

- Oxidation State Engineering: The demonstration of CMD at Pd(III) centers suggests that careful control of metal oxidation states can open new mechanistic pathways with complementary selectivity profiles [16].

- Substrate Scope Expansion: The predictive capability of the CMD model enables rational approaches to expanding substrate scope, particularly for challenging aliphatic C–H bonds where conformational flexibility and less favorable orbital interactions present additional hurdles [15].

Quantitative Analysis of CMD Systems

Recent studies provide quantitative data on reaction efficiencies across different catalytic systems and substrate classes, highlighting the impact of mechanistic variations on catalytic performance.

Table: Representative CMD Systems and Their Performance

| Catalytic System | Reaction Type | Substrate Class | Yield/TOF | Key Mechanistic Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni(OTf)₂/MesCO₂H [15] | β-C(sp³)–H Arylation | Aliphatic amides | Good to excellent yields | Ni(II)/Ni(IV) cycle with reversible C–H cleavage |

| [(η²-C₂H₄)₂Rh(μ-OAc)]₂ [17] | Nondirected Arene Alkenylation | 1,2-/1,3-disubstituted benzenes | 3-68 TOs | Mechanism switch based on arene substitution |

| Pd(III)-Pyridinophane [16] | Csp²–H Activation | Neophyl system | 44% conversion | First isolated C–H activation at Pd(III) |

| Ru-catalyzed CMD [13] | Direct Arylation | Biaryls | High FG tolerance | Late-stage synthesis of pharmaceuticals |

The Concerted Metalation-Deprotonation mechanism represents a cornerstone of modern C–H functionalization science, providing a versatile and widely applicable pathway for selective carbon-hydrogen bond cleavage. From its initial proposal in mercury chemistry to its current applications across diverse transition metals and oxidation states, the CMD paradigm continues to evolve and expand. The mechanistic insights derived from CMD studies directly inform the design of novel catalytic systems, enabling more sustainable and efficient synthetic methodologies. For drug development professionals, these advances translate to streamlined synthetic routes to complex targets, particularly through the functionalization of inert C(sp³)–H bonds that can enhance the three-dimensional character of pharmaceutical compounds. As research continues to reveal new dimensions of this fundamental process, the CMD mechanism will undoubtedly remain central to innovation in catalytic C–H activation and its applications across chemical synthesis.

The field of carbon–hydrogen (C–H) activation has experienced remarkable growth as a strategy for sustainable molecular synthesis, potentially offering high atom economy and reduced prefunctionalization requirements compared to traditional cross-coupling methodologies [18] [19]. However, this rapid expansion has revealed limitations in the classical classification system for C–H cleavage mechanisms, which has traditionally categorized reactions into distinct pathways such as oxidative addition, σ-bond metathesis, electrophilic substitution, and concerted metalation-deprotonation (CMD) [18]. These conventional classifications, often based on metal/ligand combinations or the number of atoms in the transition state, fail to adequately describe the full spectrum of observed reactivities and can lead to inconsistent terminology within the research community.

A paradigm shift is underway, moving from these segregated mechanistic categories toward a more nuanced charge transfer continuum model of reactivity [18]. This modern theoretical framework, supported by computational studies, posits that C–H cleavage mechanisms exist on a spectrum ranging from electrophilic to amphiphilic to nucleophilic character, governed by the degree of net charge transfer between molecular fragments during the transition state [18]. The factor dictating a mechanism's position on this continuum is the overall difference in charge transfer during the transition state, specifically the balance between charge transfer from a metal dπ-orbital to the C–H σ*-orbital (CT1, reverse charge transfer) and from the C–H σ-orbital to a metal dσ-orbital (CT2, forward charge transfer) [18]. This perspective fundamentally challenges the conventional segregation of mechanisms based solely on metal identity, oxidation state, or transition state geometry.

Fundamental Concepts and Terminology

Distinguishing Between Activation and Functionalization

Within C–H bond cleavage research, consistent terminology is essential for effective scientific communication. The terms "activation" and "functionalization" are often used, but require precise distinction [18]:

C–H Activation: Refers specifically to the mechanistic step involving direct cleavage of a C–H bond through interaction with a transition metal, resulting in a new carbon-metal bond. This term should not refer merely to the elongation or polarization of a C–H bond upon coordination.

C–H Functionalization: Describes the overall process wherein a C–H bond is replaced by another element or functional group, typically preceded by a C–H activation event.

Sigma and Agostic Complexes

Both sigma and agostic interactions represent crucial preliminary steps prior to C–H bond activation, involving donation of electron density from the σ-orbital of a C–H bond into an empty d-orbital on a transition metal [18]. The distinction lies in their molecular connectivity:

- Sigma Complexes: Occur through intermolecular approaches, where C–H bonds from separate molecules interact with the metal center.

- Agostic Complexes: Represent intramolecular interactions where a C–H bond within the coordination sphere of the metal donates electron density, facilitated by another primary metal-ligand interaction.

These interactions are critical for stabilizing high-energy metal intermediates and polarizing C–H bonds to enable cleavage, though sigma complexes are typically weak and rarely isolable without specialized spectroscopic techniques [18].

The Charge Transfer Continuum: Theoretical Framework

Deconstructing Traditional Mechanistic Categories

Classical C–H activation mechanisms have been historically separated into four primary categories, each with distinct characteristics. However, the continuum model reveals these as points along a reactivity spectrum rather than discrete entities.

Table 1: Traditional C–H Activation Mechanisms and Their Continuum Positioning

| Mechanism Type | Traditional Characteristics | Position on Continuum | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative Addition | Common for late transition metals, formal oxidation state increase of metal by 2 units | Nucleophilic | Three-centered transition state, common for electron-rich metals |

| σ-Bond Metathesis | Typical for early transition metals, redox-neutral process | Amphiphilic | Four-centered transition state, avoids high oxidation states |

| Electrophilic Activation | Characteristic of electron-deficient metal centers | Electrophilic | Involves partial proton transfer, common for high-valent late metals |

| AMLA/CMD | Ligand-assisted proton abstraction | Ranges from Amphiphilic to Electrophilic | Bifunctional role of ligand in proton transfer |

Quantitative Charge Transfer Parameters

The position of a mechanism on the reactivity continuum can be quantitatively described using charge transfer parameters derived from computational studies.

Table 2: Charge Transfer Parameters Across the Reactivity Continuum

| Parameter | Electrophilic | Amphiphilic | Nucleophilic |

|---|---|---|---|

| CT1 (M→σ*C-H) | Minimal | Moderate | Significant |

| CT2 (σC-H→M) | Significant | Moderate | Minimal |

| Net Charge Transfer | Electrophilic character | Balanced | Nucleophilic character |

| Typical Metal Centers | PdII, RhIII, IrIII, RuII | Intermediate states | RhI, IrI |

| Bond Cleavage Character | More heterolytic | Intermediate | More homolytic |

Experimental Validation and Methodologies

Computational Analysis Protocols

Energy Decomposition Analysis (EDA)

- Objective: Deconstruct transition state energies into physically meaningful components to quantify charge transfer characteristics.

- Methodology:

- Optimize geometry of reactants, products, and transition states using density functional theory (DFT) with appropriate functionals (e.g., B3LYP, M06-L).

- Perform single-point energy calculations with larger basis sets and dispersion corrections.

- Decompose interaction energies using EDA schemes separating Pauli repulsion, electrostatic interactions, and orbital interactions.

- Quantify charge transfer components using natural bonding orbital (NBO) analysis or charge decomposition analysis (CDA).

- Key Measurements: Calculate CT1 (dπ→σ*C-H) and CT2 (σC-H→dσ) values to position mechanism on continuum [18].

Transition State Characterization

- Objective: Identify the precise degree of C–H bond cleavage and charge transfer at the transition state.

- Methodology:

- Locate transition states using quasi-Newton methods or eigenvector-following algorithms.

- Confirm transition states with frequency calculations (single imaginary frequency).

- Analyze intrinsic reaction coordinates (IRC) to connect transition states to minima.

- Calculate bond lengths, vibration frequencies, and atomic charges at transition state.

- Interpretation: Earlier transition states with minimal bond elongation typically indicate more electrophilic character, while later transition states with significant C–H cleavage indicate nucleophilic character.

Kinetic Isotope Effect (KIE) Methodologies

Primary KIE Measurements

- Objective: Determine if C–H bond cleavage is rate-determining and probe transition state symmetry.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Prepare parallel reactions with protiated and deuterated substrates under identical conditions.

- Monitor reaction rates using GC-MS, NMR, or other analytical techniques.

- Calculate KIE = kH/kD.

- Compare observed KIE values to theoretical maximum (typically 6-7 at room temperature).

- Interpretation: Large KIE values (>3) suggest C–H cleavage is rate-determining, while small values (<2) indicate other steps are rate-limiting. KIE values must be interpreted cautiously as conclusive evidence for C–H activation being rate-determining is often misinterpreted [18].

Competitive KIE Measurements

- Objective: Obtain more accurate KIE values under identical reaction conditions.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Prepare substrates with 1:1 mixture of protiated and deuterated compounds.

- Conduct single reaction and analyze product ratio using mass spectrometry.

- Calculate KIE = ln(1 - C)/ln(1 - C × F) where C is conversion and F is fractional yield of deuterated product.

- Advantages: Eliminates experimental error from separate reactions.

Catalytic System Design for continuum Positioning

Tuning Metal and Ligand Properties

The position of a catalytic system on the charge transfer continuum can be deliberately manipulated through strategic selection of metal centers and ligand architectures.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Continuum Tuning

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Continuum Positioning |

|---|---|---|

| Precious Metal Catalysts | Pd(OAc)2, [RhCp*Cl2]2, RuCl2(p-cymene) | Provide distinct positions on continuum based on oxidation state and coordination geometry |

| 3d Transition Metal Catalysts | MnBr(CO)5, Co(Cp*), Fe(PDP) complexes | Sustainable alternatives offering unique reactivity profiles and continuum positions |

| Ligand Systems | PDP ligands, phosphines, N-heterocyclic carbenes, bipyridines | Fine-tune electron density at metal center to modulate charge transfer characteristics |

| Directing Groups | Pyridine, amides, anilides, 2-phenylpyridine | Position substrates for optimized C–H cleavage geometry and charge transfer |

| Oxidants | Ag salts, Cu(OAc)2, PhI(OAc)2, electrochemical oxidation | Regenerate catalytic species; electrochemical methods offer sustainable alternative |

Diagram: Charge Transfer Continuum in C–H Activation

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Continuum Analysis

Case Studies and Research Applications

Palladium-Catalyzed 2-Phenylpyridine Functionalization

The directed C–H activation of 2-phenylpyridines exemplifies how the continuum model provides insights into reaction design and optimization. Palladium-catalyzed systems demonstrate predominantly electrophilic character on the continuum, facilitated by the coordinating pyridine nitrogen that positions the metal center proximal to the ortho C–H bond [2]. Recent advances include electrochemical palladium-catalyzed ortho-arylation under silver-free conditions, where electricity serves dual roles in catalytic reoxidation and arenediazonium reduction [2]. This methodology achieves significant yields (75% demonstrated) with broad substrate scope and eliminates the need for hazardous chemical oxidants, aligning with sustainable chemistry principles while operating through a defined position on the charge transfer continuum.

Sustainable Catalyst Development with 3d Metals

The pursuit of sustainable C–H activation methodologies has accelerated research into 3d transition metal catalysts, which often occupy distinct positions on the charge transfer continuum compared to precious metals [19]. Notable examples include:

Iron-based Systems: The White–Chen catalyst utilizing iron complexes with pyrrolidine-pyridine (PDP) ligands achieves remarkable regioselectivity in C(sp3)-H bond oxidation through rigid ligand geometry that controls substrate access to the metal center [19]. Related iron-porphyrin and phthalocyanine systems enable nitrenoid transfer for C–H amination with high functional group tolerance.

Manganese and Cobalt Catalysts: MnBr(CO)5 enables regioselective aromatic alkenylation with anti-Markovnikov selectivity [19], while cobalt Cp* complexes facilitate domino C–H activation sequences unachievable with precious metals [19]. These systems highlight how 3d metals can offer not just sustainability advantages but complementary reactivity profiles on the charge transfer continuum.

Nickel/NHC Systems: Ni catalysts with N-heterocyclic carbene ligands enable anti-Markovnikov hydroarylation of alkenes, achieving remarkable turnover numbers (TON up to 183) through stabilizing noncovalent interactions in the transition state [19].

Research Implications and Future Directions

The charge transfer continuum model represents a fundamental shift in how C–H activation mechanisms are conceptualized, classified, and exploited for catalyst design. This framework provides researchers with a more accurate and predictive tool for understanding reactivity patterns across diverse metal/ligand/substrate combinations. For drug development professionals, this enhanced mechanistic understanding enables more rational design of C–H functionalization strategies for late-stage diversification of complex molecules, potentially streamlining synthetic routes to pharmaceutical targets.

Future research directions will likely focus on precisely mapping the continuum position for broader catalytic systems, developing quantitative descriptors for a priori prediction of continuum positioning, and designing switchable catalysts whose continuum position can be modulated by external stimuli. The integration of this continuum model with emerging computational approaches, including machine learning algorithms informed by physical principles [20], promises to accelerate the discovery and optimization of novel catalytic systems for sustainable C–H functionalization.

In the development of novel catalysts for C–H activation reaction mechanisms, the initial interaction between a metal center and an inert C–H bond represents a critical pre-activation step. These interactions, broadly classified as sigma (σ) and agostic, stabilize high-energy metal intermediates and polarize the C–H bond, setting the stage for subsequent cleavage [21]. While both involve the donation of electron density from the σ-orbital of a C–H bond into an empty d-orbital on a transition metal, their distinction lies primarily in connectivity: sigma complexes form through intermolecular approaches, whereas agostic interactions are intramolecular in nature, occurring when a C–H bond is held in the metal's coordination sphere by another primary metal-ligand interaction [21]. Understanding this nuanced difference is fundamental for researchers and drug development professionals designing more efficient and selective catalytic systems, as these weak interactions often dictate the trajectory of the entire activation process.

Defining the Interactions: Sigma Complexes and Agostic Bonds

Fundamental Concepts and Historical Context

The term "agostic," derived from the Ancient Greek word for "to hold close to oneself," was formally coined by Maurice Brookhart and Malcolm Green to describe intramolecular three-center-two-electron (3c-2e) interactions between a coordinatively-unsaturated transition metal and a C–H bond on one of its ligands [22]. This interaction represents a special case of a C–H sigma complex, historically the first to be observed spectroscopically and crystallographically due to the relative stability of intramolecular complexes [22]. Agostic interactions are now recognized as ubiquitous in organometallic chemistry, prominently featuring in alkyl, alkylidene, and polyenyl ligands, and playing decisive roles in catalytic processes ranging from alkane oxidative addition to Ziegler-Natta polymerization [23].

In contrast, sigma complexes involve similar 3c-2e bonding but occur through intermolecular interactions, such as when an alkane molecule approaches a metal center [21]. These complexes are typically weaker and more transient than their agostic counterparts, making them more challenging to isolate and characterize. The first methane sigma complex was fully characterized in solution by Goldberg and co-workers in 2009, representing a significant milestone in the field [21].

The Bonding Continuum in C–H Activation

Modern understanding, supported by computational studies, suggests that C–H cleavage mechanisms exist on a reactivity continuum rather than in segregated categories [21]. The fundamental factor dictating the mechanism is the overall degree of charge transfer during the transition state: charge transfer from a metal dπ-orbital to the C–H σ*-orbital (reverse charge transfer, CT1) and charge transfer from the C–H σ-orbital to a metal dσ-orbital (forward charge transfer, CT2) [21]. This continuum ranges from electrophilic, through amphiphilic, to nucleophilic in character, providing a more accurate framework for understanding C–H activation than classifications based solely on metal type or formal oxidation state.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Sigma and Agostic Interactions

| Characteristic | Sigma Complex | Agostic Interaction |

|---|---|---|

| Connectivity | Intermolecular [21] | Intramolecular [21] |

| Bonding Type | 3-center-2-electron (3c-2e) [22] | 3-center-2-electron (3c-2e) [22] |

| Primary Role | Stabilization of transition states; precursor to intermolecular C–H activation [21] | Activation of ligand C–H bonds; key intermediate in catalytic cycles [23] |

| Experimental Evidence | TR-IR, solution characterization at low T [21] | X-ray/N neutron crystallography, NMR (upfield shift, reduced JCH) [23] [22] |

| Typical M···H Distance | Similar range, system-dependent | 1.8 – 2.3 Å [22] |

| Typical M···H–C Angle | System-dependent | 90° – 140° [22] |

Distinguishing Features and Experimental Characterization

Geometric and Spectroscopic Parameters

The reliable identification of agostic interactions relies on a combination of crystallographic and spectroscopic data. Key geometric parameters include metal-hydrogen distances typically between 1.8–2.3 Å and M···H–C angles ranging from 90° to 140° [22]. These interactions cause a noticeable elongation of the C–H bond, often by 5-20% compared to a standard hydrocarbon bond [22].

Spectroscopically, agostic interactions impart distinct signatures in NMR spectra. The proton involved in the interaction exhibits a significant upfield chemical shift (δ = -5 to -15 ppm), appearing in the region typically reserved for hydride ligands [23] [22]. Furthermore, the coupling constant between carbon and hydrogen (¹JCH) is reduced to approximately 70–100 Hz, compared to the 125 Hz expected for a normal sp³ carbon-hydrogen bond [22]. In the infrared spectrum, the C–H stretching frequency (νC-H) of an agostic bond is characteristically low, falling within the 2700–2300 cm⁻¹ range [23].

Topological Analysis via QTAIM and ELF

For ambiguous cases or deeper theoretical insight, the Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM) and Electron Localization Function (ELF) topological analyses provide robust tools for characterizing agostic bonds. According to QTAIM, an agostic interaction is indicated by the presence of a bond critical point (BCP) between the metal and the hydrogen atom, with a Laplacian of the electron density (∇²ρBCP) typically in the range of 0.15–0.25 atomic units [23].

The ELF analysis offers a more nuanced descriptor. A σ X-H bond is considered to be in a genuine agostic interaction when the topological analysis reveals a trisynaptic basin (an basin integrating three atoms) for the protonated X-H bond, with the metallic center's contribution to this basin being strictly larger than 0.01 electron [23]. This population, when normalized, can be used to quantify and compare the relative strength of agostic interactions across different complexes. This weakening of the electron density at the C–H bond critical point correlates well with the experimentally observed lengthening of the bond and the reduction in its vibrational frequency [23].

Table 2: Experimental and Theoretical Diagnostic Tools for Agostic Interactions

| Method | Observed Feature | Diagnostic Value |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray/Neutron Crystallography | Elongated C–H bond; Short M···H contact [22] | Direct structural evidence (M···H: 1.8-2.3 Å) [22] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | ↑field 1H shift (δ -5 to -15 ppm); Reduced ¹JCH (~70-100 Hz) [23] [22] | Signature proton environment; evidence of C–H bond weakening |

| Infrared Spectroscopy | Low νC-H stretch (2700-2300 cm⁻¹) [23] | Direct measure of C–H bond weakening |

| QTAIM Analysis | Presence of M···H BCP; ∇²ρBCP ~ 0.15-0.25 a.u. [23] | Topological proof of interaction; characterizes bond nature |

| ELF Analysis | Trisynaptic C-H-M basin with metal contribution >0.01 e [23] | Quantitative measure of agostic bond strength |

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

Protocol 1: Combined NMR and Crystallographic Analysis

This protocol outlines the definitive experimental identification of an agostic interaction using a combination of spectroscopic and structural techniques, as exemplified by studies of ruthenium and titanium complexes [22].

Materials:

- Crystallographically-suitable crystals of the target complex (e.g., grown via slow vapor diffusion of pentane into a concentrated THF solution)

- Deuterated solvent for NMR (e.g., toluene-d⁸)

- NMR spectrometer with variable-temperature (VT) capability

- X-ray or neutron diffraction facility

Procedure:

- Synthesis and Crystallization: Generate the coordinatively unsaturated metal complex in situ, often by abstraction of a halide or ligand using a reagent like NaBAr⁴F in a dry, oxygen-free environment. Grow single crystals suitable for diffraction studies [24].

- Variable-Temperature NMR Analysis: Dissolve the complex in a deuterated solvent (toluene-d⁸ is suitable for organometallic complexes).

- Acquire a 1H NMR spectrum at room temperature. Identify resonances in the hydride region (δ -5 to -15 ppm).

- Record a 13C NMR spectrum or an HMQC experiment to identify the carbon atom bound to the agostic hydrogen. Measure the 1JCH coupling constant; a value of 70-100 Hz is indicative of an agostic interaction.

- Perform VT-NMR to monitor the behavior of the proposed agostic proton. The signal may broaden or shift with temperature, indicating a dynamic process [24].

- X-ray or Neutron Diffraction:

- Collect X-ray diffraction data on a single crystal at low temperature (e.g., 100 K) to minimize thermal motion and obtain precise coordinates.

- For the most accurate H-atom positions, neutron diffraction is preferred, though more rarely available.

- Solve and refine the crystal structure. Key metrics to calculate are the M···H distance (expected 1.8-2.3 Å) and the M···H-C angle (expected 90-140°) [22].

- Data Correlation: Correlate the NMR and crystallographic data. The proton identified by NMR in the upfield region should correspond to the hydrogen atom identified crystallographically with a short contact to the metal center.

Protocol 2: Topological Analysis via QTAIM/ELF

This protocol describes a theoretical methodology to unequivocally characterize and quantify an agostic interaction using electron density analysis, based on the work of Alikhani et al. [23].

Computational Resources:

- Quantum chemical software capable of QTAIM and ELF analysis (e.g., Gaussian, ADF, ORCA)

- Visualization software (e.g., Multifwn, ChemCraft)

Procedure:

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the molecular geometry of the organometallic complex. A density functional theory (DFT) method is standard, such as B3LYP with a mixed basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP for the metal, def2-SVP for other atoms).

- Wavefunction Calculation: Perform a single-point energy calculation on the optimized geometry using a high-quality basis set to generate a high-fidelity electron density map and wavefunction file.

- QTAIM Analysis:

- Calculate the electron density ρ(r) and its Laplacian ∇²ρ(r) at all points in space.

- Locate all bond critical points (BCPs) and ring critical points (RCPs).

- Identify a BCP between the metal center and the agostic hydrogen atom.

- Record the value of the electron density ρBCP and its Laplacian ∇²ρBCP at this M···H BCP. A positive Laplacian (∇²ρBCP > 0) with a value in the 0.15-0.25 a.u. range is consistent with a closed-shell (e.g., agostic) interaction [23].

- ELF Analysis:

- Perform an ELF topological analysis: η(r) = [1 + (D(r)/D₀(r))²]⁻¹, where D(r) is the excess kinetic energy density due to Pauli repulsion and D₀(r) is the kinetic energy density of a uniform electron gas.

- Identify the basins of localized electron pairs. The critical basin for identification is the protonated basin V(C,H).

- Determine the synaptic order of V(C,H). A trisynaptic basin, V(C,H,M), confirms the 3c-2e nature of the agostic bond.

- Integrate the electron population within the V(C,H,M) basin. A metal contribution to this population greater than 0.01 electrons confirms the agostic character [23].

- Use the normalized value of this population to compare the relative strength of agostic interactions across different systems.

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Agostic/Sigma Interactions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Coordinatively Unsaturated Metal Precursors (e.g., [RuCl(CO)(PPh₃)₃], Ni(I) complexes [25]) | To provide an electron-deficient metal center capable of accepting electron density from a C–H σ-bond. | The unsaturation is key. Can be generated in situ via abstraction (e.g., using NaBAr⁴F) or thermal decomposition [24] [25]. |

| Anagostic/Agostic Control Ligands (e.g., Rigid pincer ligands, constrained geometry ligands) | To provide a pre-organized framework that positions a C–H bond proximal to the metal for intramolecular (agostic) study [23]. | Helps distinguish true agostic bonds from anagostic (weaker, more electrostatic) interactions based on geometric and electronic parameters. |

| Deuterated Solvents for VT-NMR (e.g., Toluene-d⁸, THF-d⁸) | For characterizing agostic interactions via NMR spectroscopy at variable temperatures. | Low-temperature studies can "freeze out" dynamic processes, allowing observation of the agostic interaction. Toluene-d⁸ is suitable for a wide temperature range [24]. |

| Abstraction Reagents (e.g., NaBAr⁴F, [CPh₃][BAr⁴F]) | To generate a coordinatively unsaturated and often more electrophilic cationic metal center by abstracting a halide or other anionic ligand. | The weakly coordinating BAr⁴F anion prevents unwanted coordination, allowing the C–H bond to interact with the metal [24]. |

| Computational Software (e.g., Gaussian, ADF with QTAIM/ELF modules) | For topological analysis of electron density to confirm and quantify the agostic interaction. | Essential for providing theoretical validation and deep electronic insight complementary to experimental data [23]. |

The precise understanding of sigma and agostic interactions represents more than an academic exercise; it is a cornerstone for the rational design of novel catalysts for C–H activation. Recognizing that these interactions exist on a continuum of charge transfer provides researchers with a refined framework to manipulate metal center electronics and ligand architecture [21]. For instance, the discovery of strong agostic interactions driven by nickel 4p orbitals in d⁹ Ni(I) complexes, rather than the traditional 3d orbitals, unveils a novel bonding mode that could be exploited in catalyst design for enhanced activity or selectivity [25]. Furthermore, the ability to distinguish between a transient sigma complex and a more structured agostic interaction allows for the tailored development of catalysts that can either capture inert hydrocarbon substrates or direct functionalization to specific positions on a complex molecule. As characterization techniques, particularly advanced topological analysis of electron density, continue to evolve, so too will our capacity to engineer these crucial pre-activation steps, ultimately enabling more efficient and sustainable synthetic methodologies in both academic and industrial settings.

Alkanes, major components of natural gas and petroleum, represent the most cost-effective and abundant precursors for industrial chemical production. [8] Their general chemical formula of C~n~H~2n+2~ belies a fundamental chemical inertness that has long frustrated synthetic chemists. These simple hydrocarbons consist only of strong C(sp³)-H and single C(sp³)-C(sp³) bonds, rendering them among the least reactive organic molecules. [26] This inertness is reflected in the extreme conditions required for industrial alkane transformations, where heterogeneous catalysts operate at 400-600°C in (hydro)cracking or reforming processes. [26] The chemical stability of alkanes arises from their robust and weakly polarized C-H bonds, which are thermodynamically strong and kinetically inactive. [8] Consequently, alkanes are primarily used as fuels, with their bond energy released as heat rather than leveraged for synthetic applications.

The efficient and selective activation of alkane C-H bonds under mild conditions represents a promising avenue with considerable economic and environmental implications for sustainable chemistry. [8] Successful functionalization could enable the direct conversion of abundant low-value saturated hydrocarbons into valuable chemicals, potentially revolutionizing approaches to chemical synthesis. However, this goal faces significant challenges, including the control of regioselectivity in molecules where multiple C-H bonds have similar bond dissociation energies (BDEs), and the tendency for functionalized products to be more reactive than starting materials, creating over-functionalization issues. [26]

Table 1: Bond Dissociation Energies of Alkane C-H Bonds

| Bond Type | Bond Dissociation Energy (kcal mol⁻¹) |

|---|---|

| Primary (1°) | 101 |

| Secondary (2°) | 99 |

| Tertiary (3°) | 96 |

Fundamental Mechanisms in C-H Activation

The field of alkane C-H bond activation has been extensively studied for more than four decades, with various mechanistic pathways established for metal-mediated processes. [8] Conventional classification of these mechanisms relies on overall stoichiometry, but this approach can be ambiguous and sometimes problematic. [8] Advanced analytical techniques, including density functional theory (DFT) calculations combined with intrinsic bond orbital (IBO) analysis, have provided deeper insights into electron flow during these critical reactions.

Primary Mechanistic Pathways

Oxidative Addition typically occurs in low-valent, electron-rich metal complexes with strongly donating ligands. [8] The reaction progresses through a three-membered ring transition state, with both the metal's oxidation state and coordination number increasing by two. Early experiments by Bergman and Graham demonstrated that upon irradiation, complexes such as (Cp)(PMe~3~)Ir(H)~2~ and (Cp)(CO)~2~Ir could undergo reductive elimination to form reactive species that insert into alkane C-H bonds. [8] Modern computational studies reveal that in oxidative addition, the CH~3~ moiety in methane uses an electron pair from the cleaved C-H bond to form a σ-bond with the metal, while the electron pair that accepts the proton is derived from the metal's d-orbitals. [8]

σ-Bond Metathesis typically involves early transition metals that lack d-electrons available for oxidative addition. [8] This process unfolds via a four-centered transition state, ultimately leading to substitution of the M-R' σ-bond with an M-R σ-bond while preserving the metal's oxidation state throughout the reaction. The distinguishing electronic feature is that the electron pair accepting the proton results from metal-ligand σ-bonds. [8]

1,2-Addition is generally associated with early transition metals, where a C-H bond adds across an M-X double (or triple) bond to form M-C and X-H bonds. [8] The oxidation state of the metal remains unchanged throughout this process. In this mechanism, the electron pair that accepts the proton arises from the π-orbital of metal-ligand multiple bonds. [8]

Electrophilic Activation requires coordination of an electropositive metal that withdraws electron density from C-H bonds, enhancing hydrogen atom acidity and facilitating abstraction by a lone pair from an internal or external base. [8] The reaction can proceed through four- or six-centered transition states, with the proton-accepting electron pair coming from ligand lone pairs. [8]

Figure 1: C-H Activation Mechanistic Pathways

Catalytic Systems for Alkane Functionalization

Transition Metal Catalysts

Palladium Catalysts have emerged as particularly versatile for C-H activation transformations. [2] Palladium's intermediate atomic size contributes to a broad range of reactivity and moderate stability of organopalladium compounds. [2] The compatibility of Pd^II^ catalysts with oxidants and their ability to selectively functionalize cyclopalladated intermediates make them particularly attractive. [2] Furthermore, organopalladium complexes feature non-polar C-Pd bonds due to palladium's moderate electronegative nature (2.2 on the Pauling scale), resulting in excellent chemoselectivity and minimal reactivity with polar functional groups. [2] Recent advances include electrochemical palladium-catalyzed ortho-arylation under silver-free conditions, where electricity eliminates the need for hazardous or expensive chemical oxidants. [2]

Rhodium and Iridium Complexes have demonstrated remarkable efficiency in C-H activation processes. Studies using [(η²-C₂H₄)₂Rh(μ-OAc)]₂ as a catalyst precursor with Cu(OPiv)₂ as the oxidant have shown interesting regioselectivity patterns in the ethenylation of disubstituted benzenes. [27] Quantum mechanics DFT calculations reveal that the C-H activation step can occur by two different mechanisms, with electronic properties of substituents changing the preferred C-H bond-breaking mechanism. [27]

Iron-Based Catalysts represent a more sustainable alternative to precious metals. Recent research has discovered that iron(III) salts containing weakly coordinating anions can effectively catalyze direct activation of C(sp²)-H and C(sp³)-H bonds without directing group assistance. [28] This mechanism, which can be extended to other first-row transition metals including Co(II), Ni(II), and Cu(II), has enabled efficient H/D exchange reactions for aromatic C(sp²)-H bonds and β-C(sp³)-H bonds of alkyl substituents. [28] Iron(III) perchlorate in particular has shown excellent catalytic activity in deuterotrifluoroacetic acid solvent systems. [28]

Emerging Catalytic Platforms

Copper-Based Catalysts are gaining attention through initiatives like the CUBE project, which aims to unravel the secrets of Cu-based biological and synthetic catalysts for C-H activation. [29] This research synergistically investigates Cu-containing biological enzymes (LPMOs) and synthetic catalysts like Cu-zeolites and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) to develop new design principles for C-H activation chemistry. [29]

Mechanochemical Approaches offer alternative activation methods. Ball mill mechanosynthesis provides a method for direct C-H activation to prepare NC palladacycle precatalysts via liquid-assisted grinding (LAG). [30] Methanol and dimethylsulfoxide serve as non-innocent LAG reagents that coordinate to the Pd center and produce more reactive intermediates to speed reactions. [30] Kinetic modeling results are consistent with a mechanism of nucleation and autocatalytic growth in these processes. [30]

Table 2: Comparison of Catalytic Systems for Alkane Functionalization

| Catalyst Type | Key Features | Mechanism | Substrate Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palladium Complexes | Moderate electronegativity, non-polar C-Pd bonds, oxidant compatibility | Oxidative addition, electrophilic substitution | sp² and sp³ C-H bonds, wide functional group tolerance |

| Rhodium/Iridium Complexes | Electron-rich centers, efficient C-H insertion | Oxidative addition, σ-bond metathesis | Alkanes, arenes, high regioselectivity |

| Iron Catalysts | Abundant, sustainable, weakly coordinating anions | Direct C-H activation without directing groups | Aromatic C-H, β-sp³ C-H in alkyl substituents |

| Copper Systems | Biological relevance, MOF frameworks | Oxidant activation by O₂, N₂O, H₂O₂ | Resilient C-H bonds in hydrocarbons |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Directed C-H Activation Protocol

Directed C-H activation using palladium catalysts has been extensively developed for 2-phenylpyridine systems. The general methodology involves:

Reaction Setup: In a typical procedure, 2-phenylpyridine (1.0 equiv), Pd(OAc)₂ catalyst (5-10 mol%), oxidant (1.5-2.0 equiv), and solvent are combined in a reaction vessel. [2] The mixture is stirred under inert atmosphere at elevated temperatures (80-120°C) for 12-24 hours.

Directing Group Strategy: The pyridine nitrogen serves as an effective coordinating atom that binds to palladium, forming (pyridine)N-Pd bonds that direct ortho-functionalization. [2] This coordination creates a thermodynamically or kinetically preferred metallacycle intermediate through transition metal coordination to the heteroatom of the directing group. [2]

Electrochemical Variation: Recent advances employ electrochemical conditions with 2-phenylpyridine, arenediazonium tetrafluoroborate salt, Pd(OAc)₂ catalyst, K₂HPO₄, and nBu₄NF in an undivided cell setup. [2] Electricity plays a dual role in both catalytic reoxidation and reduction of arenediazonium ion, eliminating need for chemical oxidants. [2] Optimal current values must be maintained, as deviation to lower or higher values reduces yields. [2]

Mechanochemical C-H Activation

Ball mill mechanosynthesis represents an innovative approach to C-H activation:

Liquid-Assisted Grinding (LAG): Reactions are performed using mechanical grinding in the presence of small amounts of liquid additives such as methanol or dimethylsulfoxide. [30] These non-innocent LAG reagents coordinate to the Pd center and produce more reactive intermediates. [30]

Kinetic Profile: The process follows a nucleation and autocatalytic growth mechanism, as established through kinetic modeling studies. [30] This method enables direct C-H activation without traditional solvent media, offering advantages in sustainability and reaction efficiency.

H/D Exchange for Mechanism Elucidation

Deuterium labeling provides powerful mechanistic insights:

Catalytic System: Iron(III) perchlorate (15 mol%) in deuterotrifluoroacetic acid (TFA-d, 0.1 M) at 70°C for 12 hours. [28] This system enables H/D exchange at both aromatic C(sp²)-H bonds and β-C(sp³)-H bonds of alkyl substituents.

Substrate Scope: The methodology applies to alkyl benzenes, dialkyl benzenes, poly-substituted alkyl benzenes, dimethylnaphthalenes, halobenzenes, and diaryl ethers. [28] Deuteration degrees typically range from 84-100% D for most substrates.

Mechanistic Implications: The effectiveness of weakly coordinating iron(III) salts suggests direct C-H bond activation without requirement for pre-coordination or directing groups, representing a fundamental advancement in C-H activation understanding. [28]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for C-H Activation Studies

| Reagent/Catalyst | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Palladium Acetate (Pd(OAc)₂) | Versatile Pd precursor for catalytic cycles | Directed C-H activation, electrochemical arylation |

| Arenediazonium Tetrafluoroborate Salts | Coupling partners in Pd-catalyzed reactions | Ortho-arylation of 2-phenylpyridines |

| Copper(II) Salts (Cu(OPiv)₂) | Oxidant for catalytic turnover | Rh-catalyzed ethenylation reactions |

| Iron(III) Perchlorate (Fe(ClO₄)₃) | Catalyst for direct C-H activation | H/D exchange in arenes and alkyl substituents |

| Deuterotrifluoroacetic Acid (TFA-d) | Acidic deuterium source and solvent | H/D exchange studies, mechanistic elucidation |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Non-innocent LAG reagent | Mechanochemical C-H activation, coordination to metals |

| nBu₄NF | Additive in electrochemical systems | Electrochemical palladium-catalyzed arylation |

Reaction Mechanism Workflows

Figure 2: Electrochemical Palladium-Catalyzed Arylation Mechanism

The functionalization of alkanes via C-H activation represents a grand challenge with transformative potential for sustainable chemistry. While significant progress has been made in understanding fundamental mechanisms and developing novel catalytic systems, several frontiers demand attention. The differentiation between multiple similar C-H bonds in complex molecules remains a substantial hurdle, particularly in the absence of directing groups. Additionally, the development of catalysts based on earth-abundant first-row transition metals requires intensified research efforts.

Future directions will likely focus on biomimetic approaches inspired by enzymatic systems, advanced computational design of catalyst frameworks, and integration of electrochemical methods to replace stoichiometric oxidants. The continued elucidation of electron flow dynamics through sophisticated analytical techniques will further refine our understanding of these fundamental processes. As these challenges are addressed, alkane functionalization through selective C-H activation promises to redefine synthetic strategies in pharmaceutical, agrochemical, and materials science applications, ultimately contributing to more sustainable chemical industries.

Catalyst Design and Real-World Application in Complex Molecule Synthesis