Overcoming Light Distribution Challenges in Photoredox Catalysis: From Fundamentals to Scalable Solutions

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of light distribution challenges in photoredox catalysis, a critical bottleneck for reproducibility and scale-up in pharmaceutical and chemical synthesis.

Overcoming Light Distribution Challenges in Photoredox Catalysis: From Fundamentals to Scalable Solutions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of light distribution challenges in photoredox catalysis, a critical bottleneck for reproducibility and scale-up in pharmaceutical and chemical synthesis. We explore the fundamental principles of photon attenuation governed by the Beer-Lambert law and its impact on reaction efficiency. The review then details advanced methodological solutions, including continuous-flow microreactors and high-throughput optimization platforms, that ensure uniform light penetration. Furthermore, we examine computational modeling and reactor design strategies for troubleshooting and optimization, and present a comparative validation of batch versus flow systems. Aimed at researchers and development professionals, this guide synthesizes practical and theoretical knowledge to enable the successful implementation of robust, scalable photoredox processes in drug development and industrial manufacturing.

The Photon Dilemma: Understanding the Fundamental Limits of Light Penetration in Photoredox Chemistry

This guide provides technical support for researchers troubleshooting light-dependent reactions, with a specific focus on optimizing light distribution in photoredox chemistry experiments.

Core Principles and Definitions

What is the Beer-Lambert Law and why is it critical for photoredox chemistry?

The Beer-Lambert Law is a fundamental relationship that describes how light is attenuated as it passes through a material. It states that the absorption of light is directly proportional to both the concentration of the absorbing species and the path length the light travels through the solution [1]. For photoredox chemistry, this law is essential for predicting and optimizing the amount of light available to activate photocatalysts, directly impacting reaction efficiency and scalability [2] [3].

What is the difference between Absorbance, Transmittance, and Molar Absorptivity?

- Absorbance (A): A dimensionless quantity representing the amount of light absorbed by a sample [1] [4]. It is defined as ( A = \log{10} \left( \frac{I0}{I} \right) ), where ( I_0 ) is the incident light intensity and ( I ) is the transmitted light intensity [1].

- Transmittance (T): The fraction of incident light that passes through a sample [4]. It is often expressed as a percentage: ( \%T = \frac{I}{I_0} \times 100\% ) [4].

- Molar Absorptivity (ε): Also known as the molar extinction coefficient, this is a wavelength-dependent property that indicates how strongly a chemical species absorbs light at a given wavelength. Its units are typically L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹ [1] [5]. A higher ε means a higher probability of light absorption per mole of catalyst [1].

The relationship between absorbance and transmittance is logarithmic, as shown in the following table [4]:

| Absorbance (A) | Transmittance (%T) | Photon Flux Available for Activation |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100% | Unattenuated |

| 1 | 10% | 10% of incident light |

| 2 | 1% | 1% of incident light |

| 3 | 0.1% | 0.1% of incident light |

Quantitative Application

What is the mathematical formulation of the Beer-Lambert Law?

The standard form of the Beer-Lambert Law is: [ A = \epsilon \, l \, c ] Where:

- ( A ) is the Absorbance [1]

- ( \epsilon ) is the Molar Absorptivity (L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹) [1]

- ( l ) is the Path Length (cm) [1]

- ( c ) is the Concentration (mol·L⁻¹) [1]

This relationship means that in a photoredox reaction, the fraction of light that reaches a photocatalyst molecule in the center of a vessel depends exponentially on both the solution's concentration and the width of the reactor [6].

How do path length and concentration jointly affect light penetration?

The following workflow illustrates how path length and concentration interact to quench photon flux in a typical reaction setup. The exponential decay of light intensity is a direct consequence of the Beer-Lambert Law [6] [5].

Beer-Lambert Law Calculator for Common Experimental Parameters

Use this table to predict absorbance and the resulting transmitted light intensity for a given set of conditions. The transmitted intensity is calculated relative to an incident intensity ( I_0 = 1 ).

| Molar Absorptivity, ε (M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Path Length, l (cm) | Concentration, c (mM) | Absorbance, A | Transmitted Intensity, I / I₀ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5,000 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.32 |

| 15,000 | 1 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 0.032 |

| 5,000 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.10 |

| 15,000 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 0.0010 |

| 50,000 | 1.0 | 0.05 | 2.5 | 0.0032 |

| 50,000 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 0.56 |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Why is my photoredox reaction rate low or inconsistent, even with a powerful light source?

This is often a direct result of photon flux quenching. The Beer-Lambert Law implies that light intensity decays exponentially through a solution [6]. If your reaction mixture has a high overall absorbance, the catalyst molecules furthest from the light source may receive insufficient photons for activation.

- Primary Cause: High optical density due to excessive catalyst concentration, high substrate loading, or the use of a reaction vessel with a long optical path length.

- Diagnosis: Measure the absorbance of your reaction mixture at the irradiation wavelength using a spectrophotometer. If the total absorbance is significantly above 1, most light (>90%) is being absorbed in the first part of the reaction vessel [4].

- Solution:

- Switch to a flow reactor with a short path length (e.g., <1 mm) [3]. This is the most effective way to ensure uniform light penetration.

- Dilute the reaction mixture to reduce the concentration of absorbers.

- Optimize catalyst loading to achieve sufficient absorption without making the solution opaque.

How do I correct for the inner filter effect in my reaction setup?

The inner filter effect is the practical manifestation of the Beer-Lambert Law, where the light intensity experienced by a molecule varies significantly with its position in the vessel.

- Protocol for Mitigation:

- Path Length Reduction: Use a cuvette or reactor with a shorter path length. Halving the path length halves the absorbance, dramatically increasing transmittance [1].

- Concentration Optimization: Prepare a series of reaction mixtures with varying catalyst concentrations. Measure the absorbance at your irradiation wavelength and aim for an absorbance between 0.05 and 0.5 for relatively uniform illumination in a standard 1 cm cuvette. Avoid A > 1 [4].

- Agitation: Ensure vigorous stirring to continuously bring catalyst molecules from darker regions of the vessel into the illuminated zone.

My reaction follows the Beer-Lambert Law at low concentrations but deviates at high concentrations. Why?

This is a known limitation of the Beer-Lambert Law. Deviations at high concentrations (>10 mM) can occur due to [7] [5]:

- Molecular Interactions: At high concentrations, absorbers can dimerize or aggregate, changing their absorptivity.

- Refractive Index Changes: Significant changes in solution refractive index at high concentrations can affect the measured absorbance.

- Stray Light: Instrumental limitations can cause deviations when very little light is transmitted (high absorbance).

- Solution: Always prepare calibration curves within the concentration range where absorbance is linearly proportional to concentration. For high-concentration work, dilution is often the simplest remedy.

Advanced Topics in Photoredox Optimization

How can I leverage the Beer-Lambert Law to improve scalability and energy efficiency?

Recent research highlights strategies to move photoredox chemistry towards more bio-compatible and scalable conditions by consciously managing light absorption [2] [3].

- Strategy 1: Red-Shifted Irradiation. Using photocatalysts (e.g., porphyrins) that absorb longer-wavelength (red) light reduces scattering and allows for deeper penetration into reaction mixtures, as photon energy is inversely proportional to wavelength [2].

- Strategy 2: Flow Reactors. As indicated in mechanistic investigations, flow setups with thin channels ensure that all reaction volumes receive comparable photon flux, overcoming the penetration limits of batch reactors [3]. This has led to orders-of-magnitude improvements in quantum yield [3].

- Strategy 3: Evolving Reaction Conditions. Modern protocols are being designed with bioorthogonality in mind, operating efficiently under dilute, aqueous conditions with biocompatible reductants like NADH, which necessitates careful control over path length and concentration [2].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and their functions for setting up and troubleshooting photoredox reactions based on Beer-Lambert principles.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Relevance to Beer-Lambert & Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| Spectrophotometer | Measures the absorbance (( A )) of a solution at specific wavelengths [4]. | Critical: Used to diagnose photon flux issues by measuring the absorbance of your reaction mixture before irradiation. |

| Cuvette | Holds the sample for absorbance measurement; comes in various path lengths (e.g., 1 cm, 0.2 cm). | Using a shorter path length cuvette allows you to measure the absorbance of more concentrated samples without dilution [1]. |

| Micro Flow Reactor | A reactor with narrow internal tubing (e.g., path length < 1 mm) through which the reaction mixture is pumped [3]. | Primary Solution: Dramatically reduces the effective path length ( l ), ensuring uniform light penetration and eliminating the inner filter effect. |

| Red-Light Absorbing Photocatalyst (e.g., ZnTPP) | A photocatalyst activated by longer-wavelength red light [2]. | Red light is less energetic but scatters less and penetrates deeper into solutions, mitigating some attenuation issues. |

| Methylene Blue / Eosin Y | Common photoredox catalysts with known high molar absorptivity coefficients. | Knowing the ( \epsilon ) of your catalyst allows you to precisely calculate the required concentration ( c ) for optimal light absorption. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Inconsistent Reaction Yields

Problem: Your photoredox reaction yields are inconsistent or lower than expected between experimental runs.

Explanation: Inconsistent yields are frequently caused by non-uniform light exposure across the reaction vessel. Variations in light intensity can lead to unequal photon absorption by the photocatalyst, resulting in a fluctuating population of excited-state molecules and, consequently, unreliable catalytic cycles [8].

Solution:

- For batch reactions: Ensure the reaction vessel is positioned at a consistent and optimal distance from the light source. Use a reactor designed for good internal light penetration, and consider using a magnetic stirrer to ensure homogeneous mixing of the reaction mixture.

- For flow chemistry: Transitioning to a continuous flow reactor is highly recommended. Flow systems, particularly microreactors, provide a much higher surface-area-to-volume ratio, ensuring that all reaction fluid is exposed to a consistent light intensity, leading to superior reproducibility and yield [8].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Failed Reaction Scale-Up

Problem: A photoredox reaction that worked well on a small scale fails during scale-up.

Explanation: This is a classic symptom of a light distribution problem. In larger batch reactors, the incident light is often absorbed by the outer layers of the reaction mixture, failing to penetrate the core—an effect known as the "inner filter" effect. This creates a gradient of excited-state catalyst concentration [8].

Solution:

- Implement Flow Chemistry: Scale-up is a key advantage of flow photochemistry. Systems like oscillatory plug flow photoreactors or continuous stirred-tank reactor (CSTR) cascades are specifically designed to handle scale-up by maintaining uniform light exposure throughout the reaction volume, overcoming the limitations of traditional batch scaling [8].

- Optimize Reaction Concentration: If flow chemistry is not an option, consider diluting the reaction mixture to reduce its optical density, thereby allowing for better light penetration. However, this is often a less efficient workaround.

Guide 3: Diagnosing Unusual By-Product Formation

Problem: Your reaction produces unexpected by-products that are not present in the literature or established protocols.

Explanation: Non-uniform light exposure can create localized "hot spots" of high light intensity. These areas can over-irradiate the photocatalyst or substrates, pushing them into highly excited states or triggering alternative, unwanted reaction pathways that lead to decomposition or by-product formation [9].

Solution:

- Characterize Light Source: Profile your light source to identify and eliminate hot spots. Ensure the light output is collimated and even.

- Control Reaction Temperature: Use a temperature-controlled reactor to manage any thermal effects from the light source. This helps ensure that the observed reactivity is due to photoredox catalysis and not simple thermal effects.

- Validate with a Known System: Test your setup with a well-documented photoredox reaction to benchmark its performance and identify any deviations caused by your equipment.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is uniform light exposure so critical in photoredox catalysis?

Uniform light exposure is non-negotiable because the photocatalyst's excited state is the primary engine of the reaction. This excited state is generated directly by photon absorption. If light exposure is uneven, the concentration of active excited-state catalyst molecules becomes inconsistent. This leads to irreproducible reaction kinetics, incomplete conversion, and variable yields, fundamentally compromising the reliability of your experimental data [8].

Q2: My reaction vessel is clear, and I'm using a powerful LED. Why isn't that sufficient?

While a clear vessel and a powerful LED are good starting points, they do not guarantee uniform irradiation. Factors such as the shape of the vessel, the depth of the reaction mixture, the optical density of the solution, and the stirring efficiency all dramatically affect how light is distributed. Without precise control over these parameters, significant gradients in light intensity will exist, leading to the problems described above [10].

Q3: What are the best practices for achieving uniform light exposure in my lab?

For rigorous research, best practices include:

- Adopting Flow Reactors: Continuous flow reactors are superior for ensuring uniform light exposure to the entire reaction mixture [8].

- Leveraging Advanced Platforms: Utilize specialized equipment like the automated Photoredox Optimization (PRO) reactor, which is designed to provide precise control over light irradiance to optically thin, temperature-controlled reaction volumes [10].

- Reaction Miniaturization: Using smaller reaction volumes, as in high-throughput experimentation (HTE), reduces the path length light must travel, minimizing intensity gradients [10].

Q4: How can I quantitatively monitor the health of my excited-state catalyst?

The dynamics of the excited-state catalyst can be directly probed using transient absorption spectroscopy. This technique uses an ultrafast laser pulse ("pump") to excite the catalyst and a second, delayed pulse ("probe") to monitor its behavior. For instance, this method has been used to show that the catalyst DDQ undergoes intersystem crossing from its singlet to triplet state with a time constant of 1.5 ps, followed by vibrational relaxation in 10.9 ps [11]. Monitoring these lifetimes can confirm your catalyst is behaving as expected. The following table summarizes key quantitative data from recent studies:

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Catalyst Excited-State Dynamics

| Catalyst/System | Key Parameter | Value | Technique | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDQ | Intersystem Crossing (ISC) Time | 1.5 ps | Transient Absorption Spectroscopy | [11] |

| DDQ | Internal Conversion/Vibrational Relaxation Time | 10.9 ps | Transient Absorption Spectroscopy | [11] |

| Automated PRO Reactor | Reaction Volume for Scouting | < 10 μL | High-Throughput Experimentation | [10] |

| Automated PRO Reactor | Throughput for Analysis | 384 reactions in < 6 min. | IR-MALDESI-MS | [10] |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Validating Light Uniformity Using a Model Photoredox Reaction

This protocol uses a decarboxylative cross-coupling as a benchmark to test reactor performance [10].

1. Principle: A known, light-sensitive transformation is executed. Consistent and high yield across multiple runs demonstrates uniform light exposure and effective reactor operation.

2. Materials:

- Photoredox catalyst (e.g., Ir(ppy)₃, Ru(bpy)₃²⁺)

- Substrates for a decarboxylative coupling (e.g., N-(acyloxy)phthalimide and an aromatic olefin)

- Solvent (e.g., DMF, MeCN)

- Inert atmosphere setup (N₂ or Ar glovebox)

- Calibrated light source (e.g., blue LEDs, 450-470 nm)

- Reactor system to be tested (e.g., batch vial or flow system)

3. Procedure:

- In an inert environment, prepare a solution of your substrates and photocatalyst in a dry solvent.

- Transfer the solution to your reactor system.

- Irradiate the reaction mixture with your calibrated light source while maintaining constant temperature and stirring (if batch).

- Monitor reaction progress by TLC or LCMS until completion.

- Quench the reaction and work up the mixture.

- Isolate and purify the product to determine yield.

- Repeat the experiment at least three times to assess reproducibility.

4. Data Interpretation: High and consistent isolated yields (low standard deviation) indicate good light uniformity. Low or variable yields suggest a problem with the photoreactor setup.

Protocol 2: Probing Excited-State Dynamics via Transient Absorption Spectroscopy

This methodology is used to directly measure the kinetics of a photocatalyst's excited state, as demonstrated for DDQ [11].

1. Principle: An ultrafast laser pulse ("pump") excites the catalyst molecules. A second, delayed white light pulse ("probe") measures changes in absorption over time, revealing the lifetimes of various excited states.

2. Materials:

- High-purity photocatalyst sample (e.g., DDQ)

- Spectroscopic-grade solvent (e.g., Acetonitrile)

- Transient Absorption Spectrometer (with pump and probe beams)

- Cuvettes suitable for ultrafast spectroscopy

3. Procedure:

- Prepare a degassed solution of the photocatalyst at an appropriate optical density for the pump wavelength.

- Mount the sample in the spectrometer.

- Set the pump wavelength (e.g., 395 nm for DDQ) and power.

- Scan the probe delay time from femtoseconds to nanoseconds.

- Record the transient absorption spectra at each delay time.

- Global analysis of the data is used to extract kinetic time constants.

4. Data Interpretation: The decay of the initial excited-state absorption (ESA) and the rise of new ESA features are fit to a kinetic model. For DDQ, this revealed a 1.5 ps ISC to the triplet state and a 10.9 ps vibrational relaxation [11]. The workflow for this diagnostic process is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials for Photoredox Catalyst and Reaction Analysis

| Item | Function / Relevance |

|---|---|

| DDQ (2,3-Dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone) | An electron-deficient quinone that acts as a powerful metal-free photoredox catalyst. Its triplet state has a very high reduction potential (~3.18 V vs. SCE), enabling challenging C-H bond activations [11]. |

| IR-MALDESI-MS | Infrared Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. A high-throughput analysis technique used to rapidly quantify hundreds of crude photoredox reactions in minutes, enabling rapid screening [10]. |

| Automated Photoredox Optimization (PRO) Reactor | A specialized platform providing precise control over light irradiance to tiny (<10 μL), temperature-controlled reaction volumes. It is designed to eliminate light distribution issues for accelerated reaction scouting and optimization [10]. |

| Continuous Flow Microreactor | A reactor with small internal channels that ensures all reaction fluid is uniformly exposed to light, overcoming the inner filter effect and enabling scalable photoredox processes [8]. |

| HBDI Chromophore Analogues (e.g., TFHBDI–) | Modified chromophores (e.g., with 2,3,5-trifluorination) used to study how chemical substitution controls excited-state reactivity and pathway selectivity, such as promoting productive photoisomerization [12]. |

Scaling up photoredox chemistry from research to industrial production presents significant engineering challenges. Two of the most critical barriers are light attenuation effects and unwanted by-product formation, which become substantially more problematic as reaction volume increases. In traditional batch photoreactors, light penetration follows the Beer-Lambert Law, where intensity decreases exponentially with path length through the reaction media [13]. This physical limitation means that in large-scale batch reactors, significant portions of the reaction mixture receive insufficient photon flux for efficient photocatalyst activation, leading to inconsistent reaction rates, extended processing times, and potential accumulation of reactive intermediates that can form by-products.

The pharmaceutical industry faces particular pressure to address these challenges, as solvents constitute approximately 85% of the total chemical mass in pharmaceutical manufacturing [14] [15]. This environmental and economic driver has accelerated research into innovative reactor designs and processing methodologies that can overcome the fundamental limitations of conventional photochemical scale-up.

Understanding Light Attenuation in Photoreactions

The Fundamental Physics

Light attenuation in photochemical systems obeys the Beer-Lambert Law (A = log₁₀(I₀/I) = ε × b × c), where light intensity decreases exponentially with penetration depth [13]. The "penetration depth" - the distance light can travel through a reaction mixture while maintaining sufficient intensity for photochemical conversion - is typically less than 10 mm in systems containing photocatalysts with large molar extinction coefficients [13]. This severe attenuation means that in a large batch reactor, only a thin surface layer of the solution receives adequate illumination, while the majority of the bulk remains effectively unilluminated.

The problem intensifies in heterogeneous systems and turbid suspensions common in pharmaceutical synthesis, where solid particles further scatter and absorb light, reducing penetration and creating significant inefficiencies [14]. In scaling up photochemical reactions, simply increasing reactor size without addressing this fundamental limitation leads to dramatically reduced productivity and compromised reaction control.

Impact on Reaction Efficiency

- Reduced Photon Availability: With most reactant molecules in large batch reactors receiving insufficient light exposure, the overall reaction rate decreases disproportionately to scale increase.

- Extended Reaction Times: Processes that complete rapidly at small scales may require dramatically longer times at production scale, increasing energy consumption and production costs.

- Inconsistent Product Quality: Uneven illumination creates concentration gradients of reactive intermediates, potentially leading to variable product quality across the reactor volume.

By-Product Formation in Scaled Systems

By-product formation in scaled photochemical systems arises from multiple factors, with both chemical and physical contributors:

- Incomplete Illumination: When reactive intermediates form in illuminated zones but don't complete their reaction pathways in dark zones, they may follow alternative pathways to by-products.

- Localized Over-irradiation: Molecules near light sources may undergo secondary photoreactions when primary products accumulate due to slow mixing.

- Thermal Gradients: The significant heat generated by high-intensity light sources (over 70% of electrical power converts to heat) can create hot spots that promote thermal side reactions if not properly managed [13].

Specific By-Product Concerns

In electrochemical treatment systems (which share similarities with photochemical systems in their oxidative nature), concerning levels of toxic by-products have been documented, including:

- Inorganic by-products: Chlorate and perchlorate at concentrations thousands of times above drinking water guidelines [16]

- Organic by-products: Haloacetic acids and trihalomethanes exceeding recommended levels by 10-30,000 times after a single treatment cycle [16]

While these specific by-products relate to electrochemical wastewater treatment, they illustrate the dramatic by-product formation potential in poorly controlled oxidative systems, highlighting the importance of precise reaction control in photoredox applications.

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: How can I improve light penetration in my scaled photoredox reaction without switching to flow chemistry?

Solution: Implement a photo-mechanochemical approach using Resonant Acoustic Mixing (RAM) technology.

Detailed Protocol:

- Equipment: Commercial Resodyn LabRAM II instrument or equivalent acoustic mixer [14]

- Reactor Design: Custom-designed 3D-printed sample holder for 4 mL glass vials with modular lamp holder accommodating four LED lamps and cooling fans [14]

- Mixing Parameters: Set oscillation amplitude to 90 g acceleration (gravity = 9.81 m·s⁻²) at approximately 60 Hz frequency [14]

- Light Source: 90 W Aqua Blue LEDs positioned to illuminate the mixing vessel [14]

- Scale Considerations: The system enables parallel processing of up to 12 reactions simultaneously while maintaining excellent reproducibility [14]

Mechanism: RAM technology uses powerful acoustic fields to create intense mixing of solvent-minimized reactions, constantly bringing reactant molecules from the bulk to the illuminated surface region. This effectively eliminates the light penetration problem by ensuring all molecules periodically receive photon exposure [14].

FAQ 2: My photoredox reaction produces significant by-products at scale but not in small-scale screening. What strategies can help?

Solution: Optimize reaction conditions to ensure complete conversion while minimizing overexposure.

Key Approaches:

- Determine the Chlorination Breakpoint: In relevant systems, stop the reaction after ammonium removal is complete (the chlorination breakpoint), which has been shown to minimize by-product formation without compromising disinfection and nutrient removal [16]

- Anode Material Selection: Choose appropriate electrode materials; TiO₂/IrO₂ anodes produce fewer problematic inorganic by-products compared to boron-doped diamond anodes, though BDD may better mineralize organic by-products after formation [16]

- Enhanced Mixing: Implement RAM technology to ensure homogeneous reaction conditions, demonstrated to maintain high selectivity at scales up to 300 mmol (1500-fold scale-up) [14]

FAQ 3: How can I manage heat generation from high-intensity lights in large-scale photochemical reactors?

Solution: Implement a light-diffusing photochemical reactor (LDPR) that separates heat generation from the reaction zone.

Implementation Guide:

- Core Technology: Utilize a light guide plate (LGP), typically made of acrylic with scattering dots on the bottom, to distribute light uniformly from edge-mounted LEDs [13]

- Thermal Management: By separating the light source from the reaction vessel, LDPR technology effectively decouples photon and heat transfer, simplifying cooling requirements [13]

- Design Optimization: Use optical engineering software to simulate and optimize dot patterns for uniform light distribution across the entire reactor surface [13]

- Validation: Characterize photon flux using chemical actinometry methods (e.g., with Ru(bpy)₃Cl₂ and diphenylanthracene) to verify uniform illumination [13]

FAQ 4: What are the most effective reactor technologies for scaling photoredox cross-coupling reactions?

Solution: Consider both photo-mechanochemical and advanced flow reactors based on specific reaction requirements.

Technology Comparison Table:

| Reactor Type | Key Feature | Scale Demonstrated | Benefits | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAM Photo-Mechanochemical [14] | Resonant Acoustic Mixing + LED | 300 mmol (1500x scale-up) | Minimal solvent, high TON (9800), handles heterogeneous mixtures | Specialized equipment required |

| Light-Diffusing Photochemical Reactor (LDPR) [13] | Light guide plate with edge LEDs | 10-gram scale continuous processing | Excellent thermal management, uniform illumination | Continuous flow operation required |

| Tubular Flow Reactor [13] | Engineered channel depth within penetration depth | Multikilogram scale | Proven scalability, relatively low cost | Potential for clogging with solids |

Selection Guidance:

- For reactions with insoluble components or heterogeneous mixtures: RAM photo-mechanochemical system

- For heat-sensitive reactions or those requiring precise temperature control: LDPR

- For homogeneous systems with known kinetics: Traditional tubular flow reactor

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Photo-Mechanochemical Cross-Coupling Using RAM

Objective: Implement a scalable C-N cross-coupling reaction between 4-bromobenzonitrile and aniline with minimal solvent [14].

Reaction Setup:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Reagent Preparation:

- Charge 4-bromobenzonitrile (1a, 0.2-300 mmol) and aniline (2a, 1.2 equiv.) into a 4 mL glass vial

- Add 4CzIPN photocatalyst (0.1 mol%), NiBr₂·glyme (5 mol%)

- Include DABCO (1.0 equiv.) and Et₃N (1.0 equiv.) as bases

- Optionally add minimal DMA (0.4 mL for 0.2 mmol scale) or operate neat

Reactor Setup:

- Place reaction vial in custom 3D-printed holder in LabRAM II instrument

- Install modular lamp holder with 90 W Aqua Blue LEDs

- Purge reaction chamber with argon to create inert atmosphere

- Set acceleration to 90 g and mixing frequency to ~60 Hz

Reaction Execution:

- Initiate resonant acoustic mixing at specified parameters

- Begin irradiation with LED light sources

- Monitor reaction temperature, maintaining 25-35°C using cooling fans

- Continue reaction for 30-90 minutes depending on substrate

Workup and Analysis:

- Stop mixing and irradiation after completion

- Analyze yield by GC-FID using dodecane as internal standard

- Purify product using standard chromatographic methods if needed

Key Optimization Parameters:

- Mixing Efficiency: Higher acceleration (up to 100 g) improves mixing but may increase temperature

- Catalyst Loading: Can be reduced to exceptionally low levels (0.1 mol% photocatalyst) while maintaining efficiency

- Scale Flexibility: Same parameters effective from 0.2 mmol to 300 mmol scales without modification

Protocol: Light Distribution Characterization Using Chemical Actinometry

Objective: Quantify photon flux and distribution in novel photoreactor designs [13].

Methodology:

- Preparation of Actinometric Solution:

- Dissolve Ru(bpy)₃Cl₂ (0.5 mM) and diphenylanthracene (DPA, 25 mM) in acetonitrile

- Degas solution with nitrogen to eliminate oxygen interference

Experimental Setup:

- Circulate actinometric solution through test reactor at controlled flow rate

- For LDPR systems, ensure full coverage of light-diffusing surface

- Maintain constant temperature (25°C) using external cooling

Photon Flux Measurement:

- Expose solution to reactor light source for measured time intervals

- Monitor DPA consumption using HPLC with UV detection

- Calculate photon flux based on known quantum yield of DPA consumption

Light Uniformity Mapping:

- Measure photon flux at multiple positions across reactor surface

- Create uniformity map to identify dark spots or hot spots

- Optimize light guide plate dot patterns based on results

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Research Reagent Solutions Table

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 4CzIPN Photocatalyst [14] | Organic photoredox catalyst | Highly efficient metal-free catalyst; loadings as low as 0.1 mol% effective |

| NiBr₂·glyme [14] | Cross-coupling catalyst | Works synergistically with photocatalyst for C-N, C-O, C-S bond formations |

| DABCO [14] | Base | Critical for reaction efficiency; optimal at 1.0 equivalent in optimized system |

| Et₃N [14] | Base | Synergistic with DABCO; use 1.0 equivalent in optimized conditions |

| Ru(bpy)₃Cl₂ [13] | Chemical actinometer | For quantifying photon flux in reactor characterization studies |

| Diphenylanthracene (DPA) [13] | Actinometric compound | Used with Ru(bpy)₃Cl₂ for precise photon flux measurements |

| TiO₂/IrO₂ Anodes [16] | Electrode material | Produces fewer problematic inorganic by-products compared to BDD |

| Sea Sand [14] | Grinding agent | Alternative processing aid; less effective than optimized RAM approach |

Performance Metrics and Comparison Data

Quantitative Performance Data Table

| Performance Metric | Traditional Batch [13] | RAM Photo-Mechanochemical [14] | LDPR Flow System [13] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Demonstrated Scale | Laboratory scale | 300 mmol | Kilogram per hour |

| Typical Catalyst Loading | 1-5 mol% | 0.1 mol% PC, 5 mol% Ni | 1-2 mol% |

| Turnover Number (TON) | 100-1000 | Up to 9800 | 500-2000 |

| Solvent Volume | 10-100 mL/mmol | Near-solvent-free or minimal | 5-20 mL/mmol |

| By-product Formation | Variable, often significant | Minimal with optimized conditions | Controlled with precise residence time |

| Light Utilization Efficiency | <10% in large batches | High due to continuous mixing | >80% with engineered path length |

| Typical Reaction Time | Hours to days | 30-90 minutes | Minutes to hours |

Strategic Implementation Framework

Decision Pathway for Reactor Selection

This technical support resource demonstrates that while scale-up barriers in photoredox chemistry are significant, multiple innovative solutions now exist to overcome them. By selecting the appropriate technology based on specific reaction requirements and carefully implementing optimized protocols, researchers can successfully transition photoredox reactions from milligram to kilogram scale while maintaining efficiency and minimizing by-product formation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are quantum yield and photon flux, and why are they critical in photoredox catalysis?

Quantum yield (Φ) is the efficiency of a photochemical reaction, defined as the number of moles of product formed per mole of photons absorbed by the reaction [17]. Photon flux is the number of photons incident on a surface per unit time (often measured in einsteins per second per square meter) [17]. These parameters are foundational for optimizing photoredox catalysis as they directly determine reaction speed, efficiency, and scalability. Accurate measurement ensures reproducible results and effective process intensification, which is crucial for pharmaceutical synthesis where yield and energy efficiency are paramount [18].

2. My photoredox reaction yields are inconsistent. Could mismeasurement of photon flux be the cause?

Yes, inconsistent photon flux delivery is a primary cause of erratic yields [18]. This often stems from:

- Light Source Decay: Output of LEDs and lamps can decrease over time.

- Improper Spectral Matching: The light source's emission spectrum must align with the catalyst's absorption profile (typically within ±15 nm for optimal performance) [18].

- Inaccurate Radiometer Calibration: Uncalibrated radiometers give false flux readings.

Using chemical actinometry provides a direct, absolute method to validate your photon flux and diagnose these issues [17].

3. When should I treat my UV-LED as a monochromatic vs. a polychromatic light source?

UV-LEDs have an emission spectrum with a bandwidth (Full Width at Half Maximum, or FWHM) of approximately 20 nm [17]. Research indicates that for calculations of incident photon flux in water treatment contexts, a monochromatic approximation using the center wavelength is often sufficient and does not introduce significant error compared to a full polychromatic analysis [17]. For precise quantum yield determinations where the actinometer or reactant absorbs across a range of wavelengths, a polychromatic approach using numerical integration is recommended.

4. How can I accurately measure the photon flux in my photoreactor?

Chemical actinometry is the most reliable method. It involves using a chemical solution (an actinometer) with a known and well-established quantum yield for its photochemical reaction. By measuring the rate of product formation in the actinometer, you can back-calculate the incident photon flux. The general formula for a monochromatic source is [17]:

[ \text{Photon Flux} = \frac{\text{Rate of product formation (moles/s)}}{\text{Quantum Yield of actinometer × Area exposed (m²)}} ]

Detailed protocols for common actinometers are provided in the Experimental Protocols section below.

5. What are the key optimization targets for industrial photoredox catalysis?

For industrial applications, the following metrics are key [18]:

- Quantum Yield (Φ): Aim for >0.25 while maintaining selectivity >90%.

- Energy Efficiency: Optimized photoredox processes can consume 30-70 kWh per kg of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API), significantly less than traditional thermal methods (150-300 kWh/kg).

- Process Mass Intensity (PMI): Successful case studies have reduced PMI from 87 kg/kg API to 19 kg/kg API.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low or Inconsistent Quantum Yield

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Photon Flux Inaccuracy | Validate flux with chemical actinometry [17]. | Calibrate your radiometer regularly using a ferrioxalate or iodide/iodate actinometer [17]. |

| Light Source Mismatch | Compare the catalyst's absorption spectrum with the light source's emission spectrum. | Use a light source where the peak emission (λmax) is within ±10 nm of the catalyst's peak absorption [18]. |

| Oxygen Quenching | Run a control experiment under rigorously degassed conditions (O₂ < 1 ppm). | Integrate degassing modules or perform reactions under an inert N₂ atmosphere [18]. |

| Inner Filter Effect | Check if the reaction solution is highly absorbing, preventing light penetration. | Dilute the reaction mixture, use a flow reactor with a short path length (0.1-1 mm), or add light-scattering additives [18]. |

Issue: Poor Reproducibility Upon Scale-Up

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Uniform Light Distribution | Use computational fluid dynamics (CFD) or ray-tracing simulations to model photon distribution [18]. | Switch to a continuous flow microreactor (<500 μm channel width) for uniform illumination [18]. |

| Inconsistent Radiant Exposure | Track cumulative radiant exposure (J/cm²) over time. | Use reactors with adaptive photon flux control and integrated cooling jackets (ΔT ±0.5°C) to maintain stable conditions [18]. |

| Catalyst Decomposition | Monitor catalyst integrity via UV-vis or HPLC after extended operation. | Use heterogeneous photocatalysts for easy recovery or ensure homogeneous catalyst levels are maintained [18]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determination of Incident Photon Flux Using Potassium Ferrioxalate Actinometry

Principle: Ferrioxalate ions photoreduce to Fe²⁺, which can be quantified by forming a colored complex with 1,10-phenanthroline [17].

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

| Potassium Ferrioxalate Solution | The actinometer; absorbs UV light and generates Fe²⁺ with a known quantum yield [17]. |

| 1,10-Phenanthroline Solution | Complexes with the photogenerated Fe²⁺ to form an orange-red complex for spectrophotometric analysis. |

| Acetate Buffer (pH 4.5) | Provides the optimal acidic medium for the complex formation reaction. |

| Sulfuric Acid (0.1-0.5 N) | Used to acidify the ferrioxalate solution before irradiation and analysis. |

Methodology:

- Preparation: In safe-light conditions, prepare a 0.15 M potassium ferrioxalate solution in 0.1 N H₂SO₄.

- Irradiation: Place a known volume of the actinometer solution in your quasi-collimated beam apparatus. Irradiate for a measured time

t. - Analysis: Mix an aliquot of the irradiated solution with acetate buffer and 1,10-phenanthroline. Measure the absorbance of the Fe²⁺-phenanthroline complex at 510 nm.

- Calculation:

- Determine the moles of Fe²⁺ produced:

n_Fe = (A * V_total) / (ε * l), whereAis absorbance,V_totalis volume,εis the molar absorptivity (~11,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹), andlis the pathlength. - The photon flux

q(einstein/s) is calculated as [17]: [ q = \frac{n{Fe}}{t \times \Phi{Fe}} ] whereΦ_Feis the temperature-dependent quantum yield of ferrioxalate (e.g., ~1.25 at 254 nm).

- Determine the moles of Fe²⁺ produced:

Protocol 2: Determination of Quantum Yield for a Photoredox Reaction

Principle: The quantum yield of your reaction is determined by using a previously calibrated photon flux [17].

Methodology:

- Calibrate Photon Flux: First, determine the incident photon flux

qfor your system at the desired wavelength using Protocol 1. - Run Photoreaction: Conduct your photoredox reaction under the same geometric and irradiation conditions used for actinometry.

- Quantify Product: Use HPLC, GC, or NMR to determine the number of moles of product

n_pformed during the irradiation timet. - Calculation: The quantum yield of your reaction is [17]: [ \Phi{rxn} = \frac{np}{q \times t} ]

Experimental workflow for determining photon flux and quantum yield.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|

| Potassium Ferrioxalate Actinometer | The gold-standard for UV actinometry (works from 254-500 nm). Handle in safe-light conditions as it is highly photosensitive [17]. |

| Iodide/Iodate Actinometer | Ideal for UV-C and UV-B regions. Useful when ferrioxalate's sensitivity is problematic. The quantum yield is well-established [17]. |

| Uridine Actinometer | A biological molecule used for validation and determining quantum yields at specific wavelengths, often used in water treatment contexts [17]. |

| Iridium/ Ruthenium Photocatalysts | Common transition metal complexes (e.g., [Ir(ppy)₃], [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺) with strong absorption in the visible region (400-500 nm) and long-lived excited states [18]. |

| Organic Dyes (e.g., Eosin Y) | Cost-effective, metal-free photocatalysts for reductive quenching cycles and applications sensitive to metal contamination [18]. |

| Continuous Flow Microreactor | Provides uniform light penetration and excellent photon efficiency via short optical pathlengths (<1 mm), overcoming Beer-Lambert law limitations [18]. |

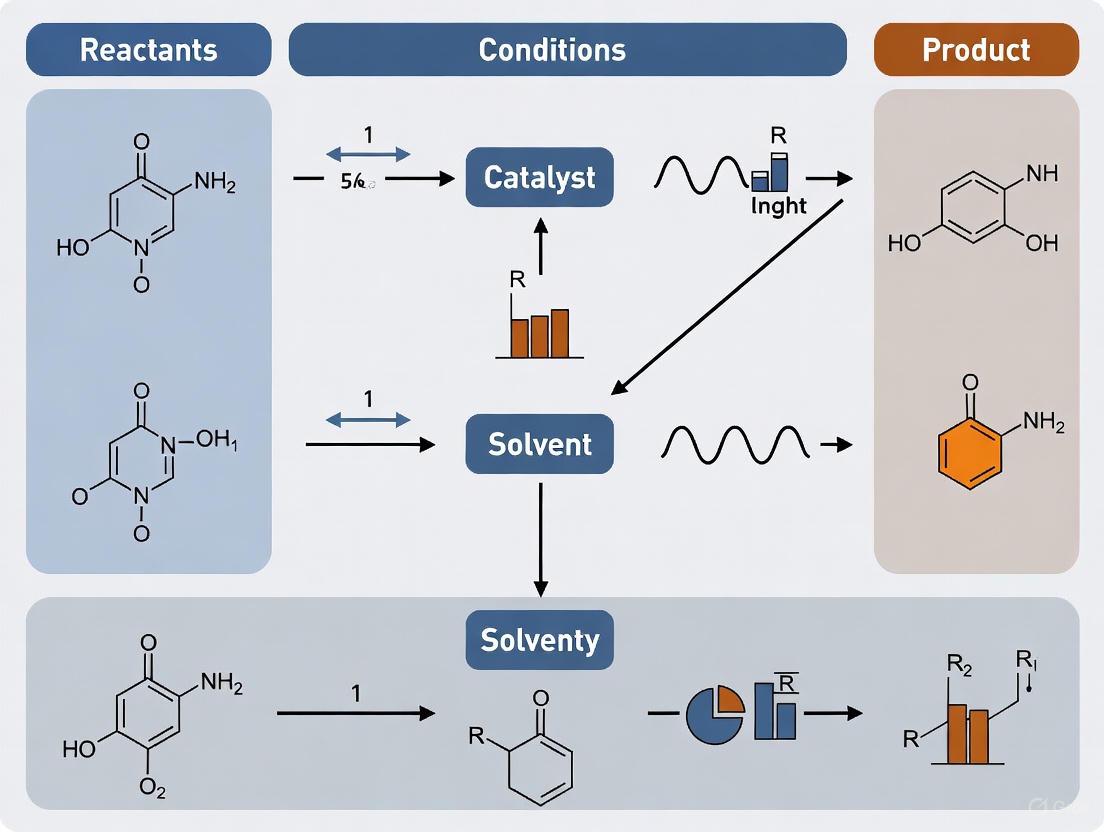

Core Photoredox Mechanism

The photoredox cycle involves three fundamental steps [18]:

- Photoexcitation: The photocatalyst (Cat) absorbs a photon of visible light, promoting it to a highly reactive excited state (*Cat).

- Single Electron Transfer (SET): *Cat engages in an electron transfer event (either oxidative or reductive quenching) with a substrate, generating a radical species.

- Catalyst Regeneration: The catalyst returns to its ground state, ready to initiate another catalytic cycle.

The photoredox catalytic cycle.

Engineering Brighter Futures: Methodologies for Superior Light Distribution in Photoredox Systems

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q1: My photoredox reaction in a continuous-flow microreactor shows inconsistent yield and poor product selectivity. What could be the cause and how can I resolve it?

Inconsistent yield and selectivity in flow photoredox reactions are frequently caused by inadequate light penetration or inefficient mass transfer. To resolve this:

- Verify Catalyst Concentration and Distribution: For heterogeneous catalysts like polymeric carbon nitride (PCN), ensure they are uniformly immobilized within the reactor. Agglomeration can block light and create shadow zones. A well-dispersed catalyst layer on a support like glass beads ensures uniform photon absorption [19].

- Check for Reactor Fouling or Blockage: Particulate matter or precipitated product can obstruct microchannels, altering flow paths and residence time. Implement an in-line filter before the reactor if your reaction mixture or reagents are prone to forming solids [20].

- Characterize the Flow Regime: Use flow visualization techniques like high-speed imaging to confirm the reactor operates in the desired flow regime (e.g., segmented or laminar). Poor mixing can lead to concentration gradients. If using a passive mixer, consider switching to a geometry that promotes chaotic advection (e.g., serpentine over straight) to enhance mixing at low Reynolds numbers [21].

Q2: I am observing a significant pressure drop across my microreactor. What are the potential sources and solutions?

A sudden or significant pressure drop indicates an obstruction or a mismatch between the reactor's design and the process stream.

- Identify Solid Formation: Monitor for the precipitation of products or intermediates. This is a common issue when product solubility is low. Increase the dilution of your reaction stream or introduce a co-solvent to maintain product solubility throughout the reaction pathway [20] [22].

- Inspect Heterogeneous Catalyst Beds: In packed-bed reactors, catalyst particles can break down or swell, compacting the bed and increasing pressure. Ensure catalyst support materials (e.g., silica, glass beads) are mechanically robust and sized appropriately to prevent them from blocking the reactor outlet frit [22].

- Confirm Fluid Properties: Ensure your reagents and solvents are compatible with the reactor's internal diameter. Highly viscous fluids or slurries can be challenging for capillary-based microreactors and may require a reactor with wider channels or active mixing [20].

Q3: The scalability of my optimized lab-scale photoredox process is yielding different results. How can I ensure a smooth scale-up?

Scale-up challenges often arise from changes in the irradiation path length and mixing efficiency.

- Maintain the Surface-Area-to-Volume Ratio: Upon scale-up, avoid simply increasing the reactor diameter, as this diminishes light penetration. Instead, number-up or scale-out by operating multiple identical microreactors in parallel. This preserves the photon and mass transport properties of the lab-scale unit [19] [20].

- Re-Optimize Residence Time: When connecting reactors in series or parallel, the total residence time and flow distribution must be carefully controlled. Use a residence time distribution (RTD) analysis to ensure consistent reaction times across all parallel units [23].

- Implement Process Analytical Technology (PAT): Integrate real-time monitoring tools like inline NMR [24] or UV/Vis spectroscopy during both development and production. This allows for immediate feedback and control, ensuring the scaled-up process remains within the optimized parameter space.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of using a continuous-flow microreactor over a batch reactor for photoredox chemistry?

- Superior Photon Transport: The high surface-area-to-volume ratio of microreactors allows for uniform irradiation of the entire reaction volume, overcoming the light penetration limitations of large batch vessels [19] [20].

- Enhanced Mass and Heat Transfer: Microreactors provide exceptionally efficient heat exchange and mixing, enabling precise temperature control and rapid reagent combination, which is crucial for highly exothermic or fast reactions [23] [21].

- Improved Safety and Scalability: They hold a small volume of reactive material at any given time, minimizing risks. Scale-up is more predictable through numbering up, rather than scaling vessel dimensions [23] [20].

- Facilitates Automation and Optimization: Their continuous nature makes them ideal for integration with automated systems and real-time analytics, enabling self-optimizing reaction platforms [24].

Q2: How can I achieve uniform mixing in a microreactor, especially for multiphase reactions?

Mixing at the microscale is dominated by laminar flow, achieved through passive or active methods.

- Passive Mixing: Relies on channel geometry to split, recombine, and stretch fluid streams, enhancing diffusion. Examples include serpentine, spiral, and split-and-recombine (SAR) geometries. These are preferred for their simplicity and lack of moving parts [22] [21].

- Active Mixing: Uses external energy (acoustic, magnetic, electrokinetic) to agitate fluids. This is more complex but can be necessary for handling slurries or very viscous fluids [21].

The following diagram illustrates how different reactor geometries influence mixing by manipulating the flow path.

Mixing Enhancement via Reactor Geometry

Q3: What materials are commonly used to construct microreactors for photochemistry, and how do I choose?

The choice of material depends on chemical compatibility, pressure/temperature requirements, and optical properties.

- Fluoropolymers (PTFE, PFA, FEP): Chemically resistant and transparent to visible light, making them excellent for visible light photoredox chemistry [22].

- Glass and Fused Silica: Offer excellent optical clarity and chemical resistance, suitable for UV and visible light applications.

- Stainless Steel and Hastelloy: Used for high-pressure/temperature reactions but are opaque. They are typically employed in sections of the flow system where light exposure is not required [25].

Quantitative Data from Literature

The following tables summarize key experimental data from recent studies on continuous-flow processes, highlighting optimized parameters and performance outcomes.

Table 1: Optimization of p-Xylene Mononitration in Continuous Flow [23]

This study demonstrates how key parameters influence conversion and selectivity in a fast, highly exothermic reaction, showcasing the control achievable with flow chemistry.

| Parameter | Variation Range | Optimum Value | Effect on Conversion | Effect on Selectivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 30 °C - 100 °C | 60 °C | Increased with temperature | Peak selectivity at 60 °C |

| H₂SO₄/HNO₃ Molar Ratio | 1.2 - >2.0 | 1.6 | Increased with ratio, then declined | Increased with ratio, then declined |

| H₂SO₄ Concentration | - | 70% | - | Peak selectivity at 70% |

| HNO₃/Substrate Molar Ratio | - | 4.4 | Reached ~100% | Improved with increasing ratio |

Table 2: Performance of Aromatic Mononitration in Flow for Pharmaceutical Intermediates [23]

This table illustrates the broad applicability and high efficiency of the developed continuous-flow nitration process for synthesizing key chemical intermediates.

| Substrate | Product | Temperature (°C) | Residence Time (s) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| o-Xylene | Nitro-o-xylene | 80 | 19 | 96.1 |

| Chlorobenzene | Nitro-chlorobenzene | 60 | 21 | 99.4 |

| Toluene | Nitrotoluene | 60 | 17 | 98.1 |

| Key Erlotinib Intermediate | - | - | - | 99.3 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Immobilization of a Polymeric Carbon Nitride (PCN) Photocatalyst in a Flow Reactor

This protocol details the preparation of a heterogeneous photoreactor for sustainable synthesis, based on the work by Wang et al. (2020) [19].

- Objective: To fabricate a fixed-bed flow photoreactor with immobilized PCN for visible-light-mediated cycloadditions.

- Materials:

- Photocatalyst: Polymeric carbon nitride (PCN, e.g., UCN derived from urea).

- Support: Commercially available glass beads or glass fibers.

- Reactor Setup: Tubular flow reactor (e.g., glass coil), syringe or HPLC pumps, tubing, and a visible light source (e.g., white LED array).

- Procedure:

- Synthesize PCN: Thermal polycondensation of urea at 550 °C for 4 hours under air to produce UCN [19].

- Immobilize Catalyst: Prepare a suspension of UCN in a suitable solvent (e.g., ethanol). Coat the glass beads or fibers by immersion or spraying. Dry the coated supports thoroughly.

- Pack the Reactor: Fill the tubular reactor homogeneously with the catalyst-coated supports. Ensure packing is dense enough to prevent channeling but not so tight as to cause excessive backpressure.

- Integrate into Flow System: Connect the packed reactor to the flow system. Ensure the reactor section is positioned within the illumination area of the light source for uniform irradiation.

- Execute Reaction: Pump the reactant solution through the reactor at the desired flow rate. Monitor pressure and collect the effluent for analysis.

Protocol 2: Automated Optimization of a Flow Reaction using Inline NMR Monitoring

This protocol describes setting up a self-optimizing flow chemistry platform, adapted from Magritek and HiTec Zang (2025) [24].

- Objective: To autonomously optimize reaction parameters (e.g., flow rates/ratio, temperature) for a model Knoevenagel condensation to maximize yield.

- Materials:

- Flow Reactor: Ehrfeld Micro Reaction System (MMRS) or equivalent.

- Pumps: Syringe pumps (e.g., SyrDos) with programmable flow rates.

- PAT Tool: Magritek Spinsolve Ultra benchtop NMR spectrometer with a flow cell.

- Automation & Control: HiTec Zang LabManager and LabVision software.

- Algorithm: Bayesian optimization algorithm.

Procedure:

- System Configuration: Set up the flow reactor, pumps, and the NMR spectrometer with its flow cell in series. Connect all components to the LabManager automation system.

- Method Programming: In the Spinsolve software, create a quantitative NMR (qNMR) method with appropriate acquisition parameters. In LabVision, define the parameters to be optimized (e.g., flow rates of two feeds) and their constraints.

- Establish Feedback Loop: Configure the software so that the yield, calculated in real-time from the qNMR spectra, is fed back to the optimization algorithm.

- Run Optimization: Initiate the autonomous optimization. The algorithm will select new parameter sets, the system will achieve steady state, measure the yield via NMR, and iteratively refine the conditions towards the global optimum.

The workflow of this integrated automated system is shown below.

Automated Flow Reactor Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Photoredox Flow Chemistry

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Heterogeneous Photocatalyst (PCN) | Metal-free, stable, and recyclable catalyst for photoredox reactions under visible light. | Urea-derived carbon nitride (UCN) for [2+2] cycloadditions [19]. |

| Corning AFR Lab Reactor | Modular microreactor system offering excellent heat transfer and mixing for process development and optimization. | Used for high-temperature/pressure nitration chemistry [23]. |

| Spinsolve Ultra Benchtop NMR | Real-time, inline reaction monitoring for automated optimization and rigorous process control. | Enabled self-optimizing Knoevenagel condensation via Bayesian algorithms [24]. |

| Glass Beads/Support Material | A substrate for immobilizing heterogeneous catalysts, creating a fixed-bed photoreactor and facilitating catalyst reuse. | Used as a support for polymeric carbon nitride catalysts [19]. |

| Ehrfeld MMRS | A modular microreactor system suitable for a wide range of reactions, including gas-liquid and photochemistry. | Served as the platform for the automated Knoevenagel reaction with inline NMR [24]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Issues & Solutions

| Problem Category | Specific Symptoms | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow Path & Fluidics | Acquisition rate decreases dramatically; pressure spikes [26] | Particle clogging in narrow tubing; gas bubble formation; precipitate from chemical reactions [27] | - Install in-line filters (e.g., 0.2-0.5 µm) [27]- Degas solvents before use- Flush system with clean, compatible solvent- Optimize reactant concentration to prevent precipitation |

| Signal & Detection | Loss or lack of expected signal; high background/noise [26] | - Photoreactor lamp intensity degradation- Poor light penetration to reaction core [27]- Non-specific dye interactions or Fc receptor binding in assays [28] | - Validate lamp output and replace if needed- Switch to flow reactor with minimized light path [27]- Use blocking reagents (e.g., normal sera, Brilliant Stain Buffer) [28] |

| Reaction Performance | Low conversion/yield; inconsistent results between runs [26] | - Suboptimal residence time- Inefficient mixing- Light wavelength mismatch with photocatalyst [27] | - Calibrate pump flow rates precisely- Use reactor designs with integrated mixing elements- Screen light sources and photocatalysts via HTE (e.g., 24-96 well photoreactors) [27] |

| Chemical Specificity | Unwanted by-products; decomposed tandem dyes [28] [26] | - Uncontrolled reaction exotherm- Tandem dye degradation- Off-target antibody binding in assays [28] | - Utilize flow's superior heat transfer [27]- Include tandem stabilizer in staining buffers [28]- Implement Fc receptor blocking steps [28] |

Advanced Workflow & Optimization Issues

| Problem | Investigation Method | Advanced Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Scale-up Translation Failure | Compare results between miniaturized HTE and target scale | Leverage flow chemistry: increase operating time without changing process parameters to maintain heat/mass transfer [27] |

| Multivariable Optimization Complexity | Use One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) approach; identify interacting variables | Implement algorithmic feedback loops (e.g., Design of Experiments - DoE) for autonomous multi-parameter optimization [27] |

| Photochemical Selectivity Issues | Analyze reaction mixture for by-products | Transition from batch to flow photoreactor to ensure uniform irradiation and precise control of reaction time [27] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Platform Fundamentals

Q1: What is the core principle behind using FLOSIM for High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) in flow chemistry?

FLOSIM integrates flow chemistry with HTE principles to enable rapid and systematic optimization of reaction conditions. Unlike traditional batch-based HTE, it allows for continuous variation of key parameters like temperature, pressure, and residence time during an experiment. This enables researchers to efficiently explore a vast chemical space, safely handle hazardous reagents through miniaturization, and achieve seamless scale-up without re-optimization by simply increasing the process runtime [27].

Q2: What are the main advantages of using a flow-based HTE approach over plate-based methods?

The key advantages include [27]:

- Investigation of Continuous Variables: Dynamic control over parameters like temperature and flow rate.

- Easier Scale-up: Moving from screening to production often requires only longer operation time, not re-optimization.

- Access to Challenging Chemistry: Enables safe handling of hazardous reagents and access to wider process windows (e.g., high temperatures/pressures).

- Superior Process Control: Enhanced heat and mass transfer in narrow tubing leads to fewer by-products and more reproducible results.

Protocol & Implementation

Q3: What is a general workflow for setting up a photoredox reaction optimization screen on the FLOSIM platform?

A robust workflow for optimizing a photoredox reaction is as follows [27]:

- Initial Broad Screening: Use a plate-based photoreactor (e.g., 96-well) to screen a wide range of catalysts, bases, and reagents to identify initial "hits."

- Hit Validation & Refinement: Transfer promising conditions to a flow reactor for preliminary validation and to refine continuous variables like residence time.

- In-Depth Optimization: Employ a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach to model the reaction landscape and find the true optimum among interacting factors.

- Stability & Feasibility Check: Conduct stability studies on reaction components to determine the number of feed solutions needed and assess risks like clogging.

- Scale-up: Systematically increase the scale in the flow reactor, adjusting parameters like light intensity and temperature as needed for the larger system.

Q4: How can I minimize non-specific background signal in my assay during intracellular staining?

For complex assays like intracellular cytokine staining, incorporate a blocking step after permeabilization. The permeabilization process exposes many new epitopes, increasing the chance for non-specific antibody binding. Using a blocking solution containing normal serum from the same species as your antibodies can significantly improve the signal-to-noise ratio by reducing this off-target binding [28].

Q5: Why is my residence time inconsistent, and how can I fix it?

Inconsistent residence time is often due to pump calibration errors, solvent viscosity changes, or particle clogging. To resolve this:

- Regularly calibrate all pumps with the exact solvents you will be using.

- Ensure all solvents are filtered and degassed.

- Monitor system pressure in real-time; a steady increase indicates a developing clog.

- Use pulse-dampeners if available to smooth out pump pulsation.

Data & Analysis

Q6: How does the platform handle data from real-time, in-line analytics for autonomous optimization?

Advanced FLOSIM setups integrate Process Analytical Technology (PAT) such as in-line IR or UV/Vis spectrometers. This real-time data stream is fed into a control algorithm (e.g., for DoE or machine learning). The algorithm analyzes the data and automatically adjusts reactor parameters (like flow rates or temperature) to steer the experiment toward the desired outcome, creating a closed-loop, autonomous optimization system [27].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Methodologies

Basic Protocol: Surface Staining for Specific Signal Detection [28] This protocol is optimized to reduce non-specific interactions in high-parameter assays.

Materials:

- Mouse serum (e.g., Thermo Fisher, cat. no. 10410)

- Rat serum (e.g., Thermo Fisher, cat. no. 10710C)

- Tandem stabilizer (e.g., BioLegend, cat. no. 421802)

- Brilliant Stain Buffer (e.g., Thermo Fisher, cat. no. 00‐4409‐75) or BD Horizon Brilliant Stain Buffer Plus

- FACS buffer

- V-bottom 96-well plates

- Centrifuge, multichannel pipettes, flow cytometer

Procedure:

- Prepare Blocking Solution: Combine 300 µl mouse serum, 300 µl rat serum, 1 µl tandem stabilizer, 10 µl 10% sodium azide (optional), and 389 µl FACS buffer to make a 1 ml mixture.

- Prepare Cells: Dispense cells into a V-bottom 96-well plate. Centrifuge at 300 × g for 5 minutes and remove the supernatant.

- Block: Resuspend the cell pellet in 20 µl of blocking solution. Incubate for 15 minutes at room temperature in the dark.

- Prepare Staining Mix: Create a master mix containing your antibodies, tandem stabilizer (1:1000), and Brilliant Stain Buffer (up to 30% v/v), diluted in FACS buffer.

- Stain: Add 100 µl of the staining mix to each sample. Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark.

- Wash: Add 120 µl of FACS buffer to each well, centrifuge, and discard the supernatant. Repeat this wash with 200 µl of FACS buffer.

- Resuspend and Acquire: Resuspend the cells in FACS buffer containing tandem stabilizer (1:1000) and acquire data on the flow cytometer.

Workflow for Photoredox Reaction Screening & Scale-up [27] The following diagram illustrates the multi-stage workflow for moving a photoredox reaction from initial screening to production scale.

Diagram 1: Photoredox reaction screening and scale-up workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Normal Sera (e.g., Rat, Mouse) | Blocks non-specific Fc receptor binding on cells, reducing background in antibody-based assays [28]. | Use serum from the same species as the primary antibodies for best results. |

| Tandem Stabilizer | Prevents the degradation of tandem dye conjugates, which can cause erroneous signal misassignment [28]. | Essential for panels using tandem dyes (e.g., Brilliant Violet). |

| Brilliant Stain Buffer | Contains PEG to minimize dye-dye interactions between polymer-based "Brilliant" dyes, preventing artifactual signals [28]. | Required for panels containing SIRIGEN Brilliant or Super Bright dyes. |

| CellBlox | A blocking agent designed to reduce non-specific binding associated with NovaFluor dyes [28]. | Specific to NovaFluor dye-containing panels. |

| Photocatalysts (e.g., Flavin) | Absorbs light energy to drive photoredox reactions, enabling unique transformations like fluorodecarboxylation [27]. | Requires matching the light source wavelength to the catalyst's absorption profile. |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | In-line instruments (e.g., IR, UV/Vis) for real-time reaction monitoring and data generation for autonomous platforms [27]. | Enables closed-loop, algorithmic optimization of reactions. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Core Principles and Common Challenges

Q1: Why is light distribution a critical parameter in photoredox catalysis? A1: Uniform light distribution is fundamental because photoredox reactions depend on the consistent absorption of photons by the catalyst to generate excited states. The Beer-Lambert Law dictates that light intensity decreases exponentially as it passes through a reaction medium. Inconsistent distribution creates zones of over-irradiation, which can degrade products or catalysts, and shadow zones where the reaction does not proceed efficiently, leading to poor conversion and longer reaction times [29] [18].

Q2: What are the most common symptoms of poor light distribution in a photoredox experiment? A2: Common observable symptoms include:

- Low Conversion Despite Long Irradiation Times: The reaction does not reach completion even with extended light exposure.

- Inconsistent Yields Between Experiments: Slight changes in reactor geometry or filling volume lead to significant yield variations.

- Formation of By-products or Decomposition: Over-irradiation of certain regions causes secondary reactions or catalyst degradation [18].

- Poor Reproducibility: Difficulty in replicating published results or previous experimental outcomes, often due to unaccounted differences in illumination [30].

Q3: How do I choose between a high-power LED and a laser-based system for my application? A3: The choice depends on the required photon flux, penetration, and reaction scale.

- High-Power LEDs: Ideal for most synthetic applications, especially in continuous flow microreactors with channel diameters below 1 mm. They offer a balance of high intensity, specific wavelength selection (typically ±15 nm), and cost-effectiveness. Modern systems allow for dynamic intensity modulation [18].

- Laser-Based Systems: Provide the highest photon flux and precise beam collimation. They are superior for applications requiring deep penetration in highly absorbing media or for initiating reactions with very high activation energies. They are particularly useful in combination with continuous stirred tank reactors (CSTRs) to improve photon penetration in larger-scale batch-flow settings [30].

Troubleshooting Guide: Light Source and Reactor Configuration

| Problem Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low reaction yield in batch | Photon flux attenuation; large reaction pathlength. | Measure distance from light source to vessel center; calculate pathlength. | Switch to a continuous flow reactor with narrow tubing (<0.5 mm ID) or use a batch reactor with a smaller internal diameter [29] [30]. |

| Reaction yield drops upon scale-up | Inadequate photon penetration at larger scale; violated geometric similarity. | Compare vessel dimensions and light source placement between small and large scales. | Implement a "numbering-up" strategy using multiple identical flow reactors or a "sizing-up" approach with smart dimensioning to preserve the micro-environment [29]. |

| Product decomposition or by-products | Localized over-irradiation; excessive photon flux. | Check if light intensity is too high. Test if pulsed light operation improves selectivity. | Reduce light intensity; incorporate alternating light-dark zones in flow systems to manage radical intermediate lifetimes [18]. |

| Poor reproducibility between runs | Inconsistent light source output; temperature fluctuations. | Use a radiometer to validate light intensity before each run. Monitor reaction temperature. | Implement Process Analytical Technology (PAT) for real-time monitoring of light intensity and temperature [29]. Ensure consistent cooling. |

| Clogging in a flow reactor | Heterogeneous reaction conditions; poor solubility. | Check for precipitation of reagents, intermediates, or bases. | Identify suitable solvents or organic bases that maintain homogeneity throughout the reaction [30]. |

Experimental Protocols and Data

Protocol 1: Rapid Optimization of Photoredox Reactions using High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE)

This protocol, based on the FLOSIM (FLow Simulation) platform, allows for the rapid identification of optimal reaction conditions that are directly translatable to flow reactors [30].

Principle: Simulate the path length and radiant flux of a flow reactor within the wells of a 96-well plate.

Methodology:

- Path-Length Matching: In a nitrogen-filled glovebox, prepare reaction mixtures in a glass 96-well plate. The volume of solution in each well is carefully controlled so that the solution height matches the internal diameter (ID) of the target flow reactor's tubing (e.g., 0.1-1 mm).

- Light Source Setup: Place the sealed plate in a benchtop HTE device equipped with high-power LEDs (e.g., Kessil PR160) and concave lenses to ensure uniform photon dispersion across all wells.

- Irradiation: Expose the plate to light irradiation for a duration equivalent to the desired residence time in the flow system.

- Analysis: Analyze the crude reaction mixtures directly using Ultraperformance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC).

- Translation to Flow: Directly apply the optimal conditions identified (wavelength, concentration, residence time) to a commercial flow system (e.g., Vapourtec E-Series) using the same ID tubing.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Spin Catalysis Effect to Suppress Back Electron Transfer

This protocol details the experimental setup for enhancing photoredox catalysis using a paramagnetic spin catalyst, as demonstrated with Gd-DOTA [31].

Objective: To suppress the detrimental Back Electron Transfer (BET) in organic dye-based photoredox catalysis by accelerating the spin conversion of Radical Ion Pairs (RIPs).

Experimental Workflow:

Key Materials and Setup:

- Reactor: Parallel light reactor (e.g., Roger RLH-18CU) with a controlled-intensity 365 nm LED light source.

- Reaction Mixture: Substrate (e.g., methyl 4-chlorobenzoate), organic dye photocatalyst (e.g., phenothiazine), spin catalyst (e.g., Gd-DOTA, 12 mol%), and hydrogen atom source (e.g., Hantzsch ester) in a mixed solvent (DMSO:H₂O, 9:1 v/v).

- Control Experiment: Run an identical reaction without the Gd-DOTA spin catalyst.

- Analysis: Monitor reaction conversion over time using Gas Chromatography (GC) with a flame ionization detector (FID).

Quantitative Performance Data:

| Performance Metric | Without Spin Catalyst | With Gd-DOTA Spin Catalyst | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to 65% Conversion | 640 minutes | 25 minutes | 25.6x acceleration |

| Spin Catalysis Effect (SCE) | 0% | 70% | - |

| Quantum Yield (Φ) Range | - | - | 0.05 - 0.3 (for homogeneous systems) [18] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Rationale | Example & Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Spin Catalyst | Suppresses Back Electron Transfer (BET) by promoting spin conversion of radical pairs, enhancing quantum yield [31]. | Gd-DOTA: A gadolinium macrocyclic complex. Its paramagnetic Gd(III) center (S=7/2) efficiently catalyzes the singlet-to-triplet spin transition of RIPs. |

| Organic Photoredox Catalyst | Absorbs light to initiate single-electron transfer (SET) events; often used for their high reducing potential in the excited singlet state [31]. | Phenothiazine-based dyes: Provide a strongly reducing excited state. Preferred over metal complexes for cost and toxicity in some applications [18]. |

| High-Power LED Light Source | Provides tunable, high-intensity visible light with specific wavelengths matched to catalyst absorption [18]. | Kessil PR160-series: Used in HTE and flow systems. Enable spectral matching (±10 nm from catalyst λmax) and intensity modulation (5-100 mW/cm²) [30]. |

| Continuous Flow Microreactor | Overcomes light penetration limits by using narrow channel diameters, ensuring uniform photon flux and preventing over-irradiation [29] [30]. | FEP Tubing Reactor: Fluorinated ethylene propylene tubing with internal diameters typically between 0.1-1 mm. Provides a short, consistent path length for illumination. |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | Enables real-time, inline monitoring of reaction progress and critical parameters for consistent control and optimization [29]. | Inline UV-Vis / UPLC: Provides continuous data on conversion and intermediate formation, enabling automated feedback control loops. |

Advanced System Diagrams

Diagram: High-Throughput Platform for Flow Reactor Simulation

This diagram illustrates the workflow of the FLOSIM platform, which bridges the gap between microscale batch optimization and scalable flow chemistry [30].

Diagram: Mechanism of Spin Catalysis for Back Electron Transfer Suppression

This diagram visualizes the mechanism by which a paramagnetic spin catalyst interferes with the electron transfer process to enhance photocatalytic efficiency [31].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Challenges in Photoredox Reactor Setups

This guide addresses specific, high-frequency issues researchers encounter when working with photoredox reactors and luminescent solar concentrators (LSCs).

FAQ 1: My photoredox reaction in a batch reactor has long reaction times and inconsistent yields. What is the underlying cause and how can I resolve it?

Answer: Inconsistent yields in batch photoredox reactors are primarily caused by the inefficient penetration of light due to the Beer-Lambert-Bouguer law [32]. In a round-bottom flask or vial, the light intensity diminishes rapidly as it passes through the reaction mixture, leading to uneven irradiation and poor reproducibility [32].

Solution: Transition to a continuous-flow microreactor [32] [33].

- Protocol: Use a transparent, perfluorinated tube (e.g., PFA or ETFE) with an internal diameter of less than 1 mm coiled around a light source (e.g., blue LEDs) [32]. The small diameter ensures a high surface-area-to-volume ratio, providing uniform light irradiation to the entire reaction volume and significantly reducing reaction time and byproduct formation [32].

- Expected Outcome: Enhanced photon transport, more reproducible outcomes, and easier scalability compared to batch reactors [32].

FAQ 2: The temperature gradient within my solar pyrolysis reactor is causing hot spots and thermal stress. How can I achieve a more uniform temperature distribution?

Answer: Parabolic trough concentrators (PTCs) often result in a non-uniform flux and temperature distribution on the reactor surface [34]. This uneven heating creates thermal stress, reduces the reactor's lifespan, and can impair process efficiency [34].

Solution: Integrate internal fins to enhance heat transfer uniformity.

- Protocol: Design and install pitchfork-shaped fins inside the reactor tube. A numerical study showed that a design with 8 fins significantly improves temperature distribution [34].

- Implementation:

- Model the photothermal coupling process using Monte Carlo ray tracing (MCRT) and finite element method (FEM) to simulate performance [34].