Semi-Empirical Methods vs. DFT for Reaction Barrier Calculation: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Accurately calculating reaction energy barriers is crucial for modeling biochemical reactions and drug mechanisms, but the computational cost of high-accuracy methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) can be prohibitive for...

Semi-Empirical Methods vs. DFT for Reaction Barrier Calculation: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

Accurately calculating reaction energy barriers is crucial for modeling biochemical reactions and drug mechanisms, but the computational cost of high-accuracy methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) can be prohibitive for large systems. This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of semi-empirical methods as an alternative to DFT for barrier calculations, exploring their foundational principles, key methodologies like PM7 and DFTB, and practical applications in studying hydrogen atom transfer in proteins and transition metal complexes. We offer troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls and a comparative validation of accuracy and computational efficiency, equipping researchers in drug development with the knowledge to select and optimize the right computational tool for their specific projects.

The Quantum Chemistry Landscape: Understanding the Theory Behind Semi-Empirical and DFT Methods

In computational chemistry, the journey from the fundamental Schrödinger equation to practical applications involves a critical balance between computational cost and predictive accuracy. The Schrödinger equation provides the foundational theory for understanding many-electron systems but is computationally intractable for all but the smallest molecules. This has led to the development of a hierarchy of computational methods, with semi-empirical (SE) methods and Density Functional Theory (DFT) occupying crucial positions in the researcher's toolkit. SE methods, which approximate the Schrödinger equation by incorporating empirical parameters, offer remarkable speed advantages—often being several orders of magnitude faster than standard DFT calculations with medium-sized basis sets [1]. However, this efficiency comes with potential trade-offs in accuracy, particularly for reaction barrier predictions essential in drug development and materials science. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their performance in barrier calculations, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols to inform research decisions.

Theoretical Foundations: From First Principles to Approximations

The Schrödinger Equation and Its Approximations

The Schrödinger equation is the cornerstone of quantum chemistry, describing the behavior of electrons in atoms and molecules. However, its exact solution is only possible for very simple systems, necessitating a series of approximations:

Ab Initio Methods: These methods, such as Hartree-Fock and post-Hartree-Fock approaches, attempt to solve the electronic structure problem from first principles without empirical parameters. While accurate, they are computationally demanding and scale poorly with system size [2].

Density Functional Theory (DFT): DFT simplifies the many-electron problem by using electron density instead of wavefunctions. Modern DFT implementations provide an excellent compromise between accuracy and computational cost for many chemical applications, making them a workhorse for computational chemists [3].

Semi-Empirical Methods: SE methods represent a further simplification by neglecting certain computationally expensive integrals and replacing them with parameters derived from experimental data or higher-level calculations. Popular SE methods include AM1, PM6, PM7, and various Density Functional Tight Binding (DFTB) approaches [1] [4].

The Density Functional Tight Binding Framework

Density Functional Tight Binding (DFTB) represents a particularly important class of SE methods derived from DFT. The DFT total energy is expanded in a Taylor series around a reference density, with truncation at different orders leading to distinct models [1]:

Truncation after specific terms gives rise to DFTB1, DFTB2 (formerly SCC-DFTB), and DFTB3 models, with increasing accuracy but also greater computational cost. The E₀ term is represented as pairwise potentials and fitted to reference data, which is why DFTB is characterized as a semi-empirical method [1].

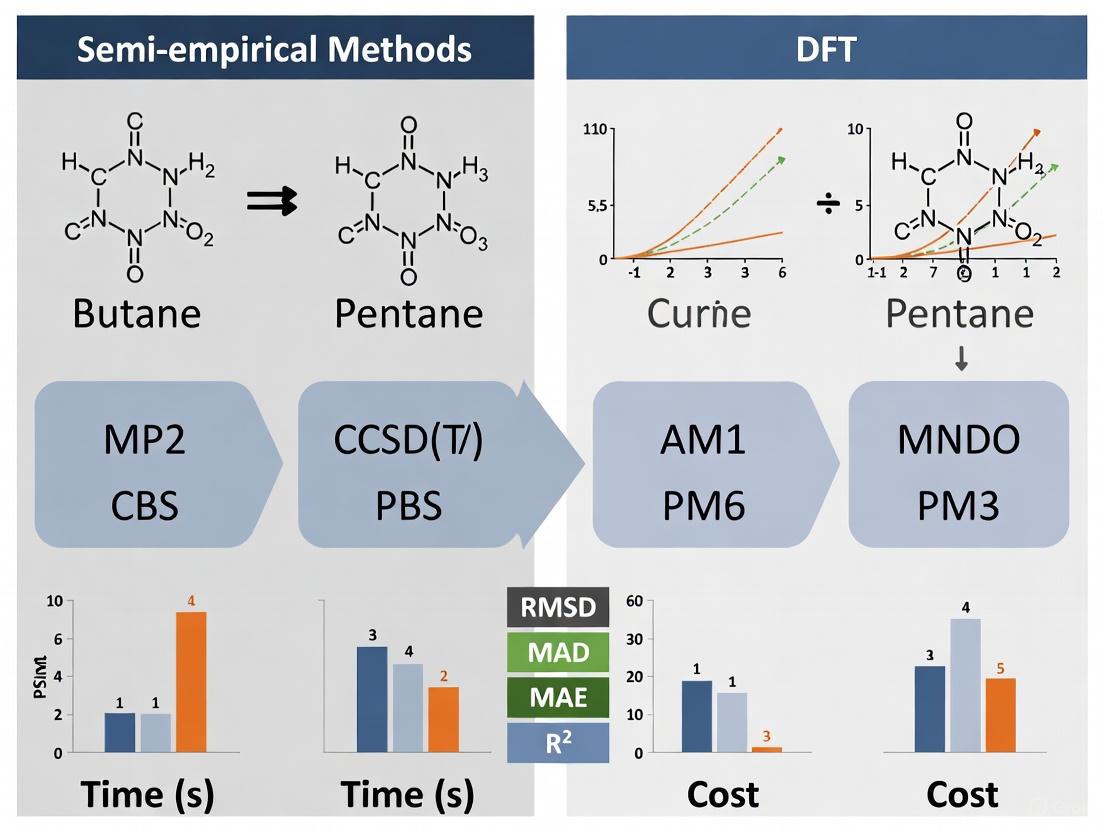

The computational efficiency of these methods follows a clear hierarchy, as illustrated in the diagram below, which shows their relative positioning in terms of speed versus accuracy:

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Benchmarking Data

Accuracy Metrics for Reaction Barrier Prediction

Multiple studies have quantitatively evaluated the performance of SE methods against higher-level theoretical benchmarks. The table below summarizes key performance metrics for various SE methods in predicting reaction barriers, a critical property in reaction mechanism analysis:

Table 1: Performance of Semi-Empirical Methods for Barrier Prediction

| Method | Class | MAE for Barriers (kcal/mol) | Computational Speed vs. DFT | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFN2-xTB | SE-DFTB | ~1.0 (with ML correction) [5] | ~1000x faster [1] | Best overall performance in benchmarks [4] | Limited transferability for phosphate chemistry [1] |

| DFTB3 | SE-DFTB | 5.71 (without correction) [5] | ~1000x faster [1] | Good for proton transfer reactions [1] | Proton affinity errors for N-containing molecules [1] |

| PM7 | HF-based SE | Not reported | ~1000x faster [1] | Includes dispersion & H-bond corrections [4] | No improvement over PM6 in some studies [4] |

| PM6 | HF-based SE | Performance similar to PM7 [4] | ~1000x faster [1] | Diatomic parameters [4] | Limited accuracy for specific systems [4] |

| AM1 | HF-based SE | Better than PM6/PM7 in some cases [4] | ~1000x faster [1] | Refinement of MNDO model [4] | Outdated compared to newer methods |

Comprehensive Benchmarking for Soot Formation Studies

A 2022 benchmark study evaluated multiple SE methods for simulating soot formation processes, providing additional insights into method performance across diverse chemical systems [4]:

Table 2: Benchmarking Results for Soot Formation Precursors (2022 Study)

| Method | RMSE (kcal/mol) | Maximum Unsigned Deviation (kcal/mol) | Qualitative Performance | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFN2-xTB | 51.00 | 13.34 | Best performance [4] | Massive reaction event sampling [4] |

| DFTB3 | 34.98 | 13.51 | Second best [4] | Primary reaction mechanism generation [4] |

| DFTB2 | 42.50 | 15.74 | Third best [4] | Preliminary screening studies [4] |

| AM1 | Not reported | Not reported | Better than PM6/PM7 [4] | Systems with known parameterization [4] |

| PM6/PM7 | Not reported | Not reported | Similar to each other [4] | When no better methods available [4] |

The study concluded that while SE methods can provide qualitatively correct reaction profiles and molecular structures, they cannot reliably provide quantitatively accurate thermodynamic and kinetic data without careful validation [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Workflow for Method Validation

The quantitative data presented in this guide were generated through rigorous benchmarking protocols. The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for validating SE methods against higher-level theoretical benchmarks:

Detailed Methodology from Representative Studies

Synergistic SE/ML Approach for Barrier Prediction

A 2022 study developed a protocol combining semi-empirical calculations with machine learning for accurate barrier prediction [5]:

Dataset Generation: 1000 unique Michael addition reactions were built using R-Group enumeration to vary four positions of a generic α,β-unsaturated carbonyl Michael acceptor core with common organic fragments [5].

Conformational Search: All structures underwent conformational searching using MacroModel with the OPLS3e force field to identify low-energy conformations [5].

Geometry Optimization: The lowest energy conformation of each structure was optimized using AM1, PM6, and ωB97X-D/def2-TZVP methods using Gaussian 16 [5].

Solvation Corrections: Single-point energy corrections incorporated solvent effects using the IEFPCM solvation model with toluene [5].

Thermal Corrections: Quasiharmonic free energies were calculated at 298.15 K and 1 mol L⁻¹ concentration using GoodVibes [5].

Feature Extraction: Simple and interpretable molecular and atomic physical organic chemical features were extracted for each Michael acceptor and transition state [5].

Machine Learning: Multiple regression algorithms were trained on an 80% training set, with hyperparameter tuning and 5-fold cross-validation to prevent overfitting [5].

This approach achieved mean absolute errors below the chemical accuracy threshold of 1 kcal mol⁻¹, substantially better than SE methods without ML correction (5.71 kcal mol⁻¹) [5].

Soot Formation Benchmarking Protocol

The soot formation study employed the following methodology [4]:

System Selection: Test sets contained soot-relevant compounds with 4 to 24 carbon atoms covering different types of reactions representing the emergence and early growth of soot precursors.

Reference Calculations: M06-2x/def2TZVPP-level DFT calculations served as the benchmark for validation.

MD Trajectory Analysis: 84 MD trajectories from simulations covering reactive and non-reactive pathways with different molecule sizes were used to validate SE methods.

Performance Metrics: Similarities of potential energy profiles were assessed using maximum unsigned deviation (MAX) and regularized relative RMSE.

Additional Validation: Methods were further tested on optimized structures, energies along intrinsic reaction coordinates, and spin density predictions.

Software and Method implementations

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for SE and DFT Calculations

| Tool Name | Type | Key Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian 16 [5] | Quantum Chemistry Software | Geometry optimization, energy calculation | Widely available; implements multiple SE and DFT methods |

| GAMESS [5] | Quantum Chemistry Software | Ab initio, DFT, and SE calculations | Free alternative for academic research |

| ORCA [5] | Quantum Chemistry Software | DFT, correlated ab initio methods | Increasingly popular for DFT calculations |

| MOPAC [5] | Semi-Empirical Package | Specialized in SE calculations | Includes AM1, PM6, PM7 methods |

| GoodVibes [5] | Analysis Tool | Thermochemical correction calculation | Computes quasiharmonic free energies |

| IEFPCM [5] | Solvation Model | Implicit solvation correction | Accounts for solvent effects in SPE calculations |

| GFN2-xTB [4] | Semi-Empirical Method | Efficient geometry optimization | Particularly good for non-covalent interactions |

| DFTB3 [1] | Semi-Empirical Method | Reaction barrier calculation | Improved performance for organic/biological systems |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that both semi-empirical methods and DFT have distinct roles in computational chemistry research. SE methods offer remarkable computational efficiency, being approximately 2-3 orders of magnitude faster than DFT calculations with medium-sized basis sets, enabling the study of larger systems and longer timescales [1]. This makes them particularly valuable for high-throughput screening and initial mechanistic explorations where computational cost is prohibitive for DFT [4].

However, this efficiency comes with important caveats. SE methods generally provide qualitative rather than quantitative accuracy, with errors frequently exceeding chemical accuracy thresholds without correction schemes [4] [5]. For critical applications requiring precise barrier heights, such as drug design or catalyst optimization, DFT remains the more reliable choice, though the computational cost is substantially higher.

The emerging paradigm of combining SE methods with machine learning correction represents a promising direction, offering DFT-quality accuracy with SE-level computational efficiency [5]. This synergistic approach maintains the mechanistic insight provided by transition state geometries while dramatically improving energy accuracy.

For researchers in drug development and materials science, strategic method selection should consider the specific research question, system size, and required accuracy. SE methods are ideal for initial screening and large-system exploration, while DFT provides more reliable quantitative data for refined studies. The continuous development of both methodologies ensures that computational chemists have an increasingly sophisticated toolkit for tackling complex chemical problems.

The Hartree-Fock Method and Its Limitations in Electron Correlation

The Hartree-Fock (HF) method is a foundational approximation technique in computational physics and chemistry for determining the wave function and energy of a quantum many-body system in a stationary state. It simplifies the intractable many-body Schrödinger equation by treating each electron as moving independently within an average field created by all other electrons, an approach known as the mean-field approximation [6] [7]. This method, also referred to as the self-consistent field (SCF) method, serves as the cornerstone for most advanced electronic structure calculations for atoms, molecules, and solids [6]. The HF algorithm typically begins with an initial guess of one-electron wave functions (spin-orbitals). These orbitals are then iteratively refined by solving a set of coupled equations—the Hartree-Fock equations—until the solution becomes self-consistent, meaning the output field is consistent with the input field [6].

Despite its historical and practical importance, the HF method possesses a fundamental limitation: its inability to describe electron correlation. Electron correlation refers to the instantaneous, repulsive interactions between electrons that cause their motions to be correlated. In other words, the position of one electron affects the likely position of another because they repel each other [8]. The HF method's mean-field approach replaces these complex individual interactions with a smoothed-out average potential. Consequently, it neglects the energy lowering that occurs because electrons naturally avoid each other, an effect known as Coulomb correlation [6] [9]. The "correlation energy" is formally defined as the difference between the exact, non-relativistic energy of a system and the energy calculated at the Hartree-Fock limit: E_corr = E_exact - E_HF [10] [8]. Although this missing correlation energy typically constitutes only about 1% of the total energy, its magnitude is on the order of chemical reaction energies and is therefore crucial for achieving chemical accuracy [9].

Quantifying the Limitations: Key Areas of Error

The neglect of electron correlation in HF theory leads to systematic and chemically significant errors in predicted molecular properties. The table below summarizes the primary limitations and their chemical implications.

Table 1: Key Limitations of the Hartree-Fock Method Due to Neglect of Electron Correlation

| Limitation | Description | Chemical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Overestimation of Binding | Total energy is always higher than the true energy (E_HF > E_exact) [8]. |

Poor description of bond dissociation; dissociation energies are predicted to be too high [8]. |

| Failure in Bond Dissociation | Cannot correctly describe the breaking of chemical bonds, particularly when leading to open-shell fragments [8]. | May predict wrong products (e.g., ions instead of neutral atoms) upon bond breaking [8]. |

| Inaccurate Reaction Barriers | Lacks accuracy for processes where electron correlation changes significantly, such as transition state formation [11] [8]. | Poor performance in calculating barrier heights for chemical reactions, limiting use in chemical kinetics [11]. |

| No London Dispersion | Cannot account for dispersion forces, which are purely correlation effects [6]. | Fails to describe weak, non-covalent interactions critical in biological systems and molecular crystals. |

These limitations can be understood through the concept of the Coulomb hole. This is the difference in the probability distribution of the interelectronic distance between a correlated calculation and the HF approximation. In HF, this distribution is uncorrelated. In reality, the likelihood of two electrons being found close together is reduced due to their mutual repulsion. The HF method completely misses this physical redistribution of electrons [9].

It is important to note that HF theory does account for Fermi correlation, which arises from the Pauli exclusion principle and is built into the method through the use of antisymmetric Slater determinant wave functions. This prevents two electrons with the same spin from occupying the same spatial orbital. The limitation discussed here specifically concerns the missing Coulomb correlation [6] [9].

Beyond Hartree-Fock: Post-Hartree-Fock and DFT Correction Schemes

To overcome the limitations of HF, a suite of more advanced methods, collectively known as post-Hartree-Fock methods, have been developed. These methods use the HF wavefunction as a reference and then add descriptions of electron correlation. Furthermore, Density Functional Theory (DFT) offers an alternative pathway that incorporates correlation from the outset. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between these different computational approaches.

Diagram 1: A taxonomy of computational chemistry methods showing how post-HF, DFT, and semi-empirical methods relate to and build upon the foundational Hartree-Fock method.

Key Post-Hartree-Fock Methods

- Configuration Interaction (CI): This method expands the wavefunction as a linear combination of the HF reference Slater determinant and other determinants representing excited electron configurations (e.g., single, double excitations). The coefficients are determined variationally. Full CI (FCI), which includes all possible excitations, provides the exact solution within the given basis set but is computationally prohibitive for all but the smallest systems [10] [8].

- Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory: This is a computationally efficient family of methods that treat electron correlation as a perturbation to the HF Hamiltonian. The second-order correction (MP2) is widely used for its favorable balance of cost and accuracy, particularly for dynamic correlation [8].

- Multi-Configurational Self-Consistent Field (MCSCF): Methods like CASSCF are designed to handle static correlation, which occurs when a single Slater determinant is insufficient to describe the system (e.g., bond breaking, diradicals). MCSCF optimizes both the orbital coefficients and the configuration expansion coefficients simultaneously [10].

- Coupled Cluster (CC): This method uses an exponential ansatz for the wavefunction and, at levels like CCSD(T) (often called the "gold standard"), delivers exceptionally high accuracy for dynamic correlation, albeit at a high computational cost.

The Density Functional Theory (DFT) Pathway

DFT takes a fundamentally different approach by expressing the total energy as a functional of the electron density, rather than the wavefunction. In practice, DFT calculations apply a correlation correction to a single Slater determinant. The critical component is the exchange-correlation (XC) functional, which must approximate all non-classical electron interactions. The existence of a unique and variational XC functional is a cornerstone of modern DFT [9]. The development of accurate XC functionals remains an active area of research, as their quality dictates the accuracy of the calculation [12].

Semi-Empirical Methods

Semi-empirical methods are derived from HF or DFT by neglecting and approximating specific electronic integrals. Parameters are then introduced and determined from reference data or experimental fitting, making these methods about 2-3 orders of magnitude faster than standard DFT. Density Functional Tight Binding (DFTB) is a prominent example derived from DFT, offering a useful compromise between speed and quantum mechanical accuracy for large systems [1].

Comparative Performance in Barrier Height Calculations

The performance of different methods is sharply highlighted in the calculation of reaction barrier heights, a critical parameter in chemical kinetics. A 2025 benchmark study by Liu et al. categorized reactions based on the strength of electron correlation effects, providing a clear framework for evaluating methods [11].

Table 2: Performance of Computational Methods on Barrier Heights Categorized by Electron Correlation Strength (Root-Mean-Square Deviation, RMSD, in kcal/mol)

| Method Category | Specific Method | "Easy" Weak Correlation | "Intermediate" Correlation | "Difficult" Strong Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory | ωB97X-D3 (Hybrid GGA) | Low errors (comparable to high-quality benchmarks) | Performance consistently worse | Largest errors |

| ωB97M(2) (Double Hybrid) | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | |

| Hartree-Fock | Restricted HF (RHF) | Not directly stated | Exhibits spin symmetry breaking | Highly inaccurate due to lack of correlation |

| Post-Hartree-Fock | κ-OOMP2 (Orbital-Optimized MP2) | Not specified | Stable orbitals at this level | Not specified |

Data adapted from Liu et al., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2025 [11]. Note: The study emphasizes that HF exhibits spin symmetry breaking for the "intermediate" subset, and standard DFT errors become largest for the "difficult" subset involving strongly correlated species.

The study strongly recommends orbital stability analysis as a best practice for DFT calculations in chemical kinetics. This analysis helps diagnose the expected accuracy; for systems where restricted HF orbitals are unstable, spin-polarized solutions or methods that better handle strong correlation (like multi-reference methods) are necessary to reduce large errors [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Electronic Structure Calculations

Table 3: Key Computational "Reagents" and Their Functions in Electronic Structure Studies

| Research Reagent / Method | Primary Function | Key Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Provides a reference wavefunction and initial guess for more advanced calculations. | Fast but inaccurate for correlated systems; use for pre-optimization or as a starting point. |

| MP2 Perturbation Theory | Efficiently recovers a large fraction of dynamic electron correlation. | Better for weak correlation; can fail for systems with significant static correlation (e.g., stretched bonds). |

| CASSCF / MCSCF | Handles static correlation and multi-reference character in wavefunctions. | Requires physico-chemical intuition to select the "active space"; computationally demanding [10]. |

| Coupled Cluster (e.g., CCSD(T)) | Delivers high-accuracy, benchmark-quality energies for systems with dominant dynamic correlation. | The "gold standard" but computationally very expensive; often limited to small molecules. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Balances computational cost and accuracy by incorporating correlation via a functional. | Accuracy is functional-dependent; standard GGAs fail for dispersion forces; hybrids perform better but are more costly [11] [1]. |

| Density Functional Tight Binding (DFTB) | Provides a quantum-based method for large systems and long time-scale molecular dynamics. | A semi-empirical method; speed comes with transferability trade-offs; parameters are element-specific [1]. |

| Empirical Dispersion Corrections | Adds missing London dispersion interactions to HF, DFT, or DFTB calculations. | Essential for describing non-covalent interactions in biological molecules and molecular crystals [1]. |

Experimental Protocols for Method Benchmarking

Benchmarking the performance of computational methods like HF, post-HF, and DFT requires rigorous protocols. A standard approach involves comparing calculated properties against a trusted set of reference data, which can be highly accurate theoretical results or experimental measurements.

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Against a Diverse Chemical Dataset

- Select a Benchmark Set: Use a comprehensive and diverse dataset such as the RDB7 (11,926 reactions) or GMTKN-24 [11] [1]. These sets cover a wide range of chemical properties like reaction energies, barrier heights, and non-covalent interactions.

- Perform Orbital Stability Analysis: As per Liu et al., categorize reactions into "easy," "intermediate," and "difficult" subsets based on the stability of the HF or Kohn-Sham orbitals. This diagnoses the expected level of electron correlation and helps interpret results [11].

- Compute Target Properties: Run single-point energy calculations or geometry optimizations on the defined molecular structures using the methods under investigation (e.g., HF, MP2, various DFT functionals).

- Calculate Statistical Errors: For each method and reaction subset, compute statistical measures like Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) and mean absolute error against the reference values.

- Analyze and Compare: Identify which methods perform robustly across different correlation regimes and which fail specifically on "difficult" strongly correlated systems.

Protocol 2: Assessing Method Performance for Specific Electron Correlation Effects

- System Selection: Choose a model system where the correlation effect of interest is pronounced. For example, use the H₂ molecule at various bond lengths to study bond dissociation, or a stacked benzene dimer to study dispersion interactions [8] [9].

- High-Level Reference Calculation: Perform a calculation with a high-level method like Full CI or CCSD(T) using a large basis set to establish a near-exact reference potential energy curve or interaction energy [9].

- Compare Method Performance: Calculate the same property using HF, post-HF, and DFT methods.

- Quantify the Correlation Energy/Effect: For energy, directly compute

E_corr = E_exact - E_HF. For dispersion, compare the binding curve from a method without dispersion correction to the reference. For the Coulomb hole, compute the difference in intracule distribution functions:ΔD(r) = D_FC(r) - D_HF(r)[9]. - Visualize Results: Plot potential energy curves or Coulomb holes to visually demonstrate the limitations of HF and the improvements offered by more advanced methods.

The Hartree-Fock method stands as a monumental achievement in theoretical chemistry, providing the foundational language and starting point for virtually all subsequent ab initio developments. However, its neglect of Coulomb electron correlation imposes clear and consequential limitations on its predictive power, particularly for processes involving bond dissociation, transition states, and weak intermolecular forces. The development of post-Hartree-Fock methods and DFT represents a concerted effort to correct this fundamental flaw. As benchmark studies on challenging problems like barrier heights demonstrate, the choice of method is critical. While HF is insufficient for quantitative kinetics, modern DFT functionals and post-HF methods offer a hierarchy of solutions, each with its own trade-off between accuracy and computational cost. For researchers, particularly in fields like drug development where non-covalent interactions are paramount, this landscape necessitates a careful, informed selection of computational tools, often guided by orbital stability analysis and benchmarked against reliable data, to ensure physically meaningful and chemically accurate results.

Semi-empirical quantum mechanical methods represent a critical compromise in computational chemistry, balancing theoretical rigor with practical computational cost. These methods are simplified versions of Hartree-Fock theory that incorporate empirical corrections derived from experimental data to improve performance and dramatically reduce calculation time. The foundational approximation for many modern semi-empirical methods is the Neglect of Diatomic Differential Overlap (NDDO), which eliminates all two-electron integrals involving two-center charge distributions [13]. This approximation, along with others, enables calculations that are several orders of magnitude faster than standard density functional theory (DFT) approaches, making them particularly valuable for rapid screening of large molecular systems and reaction spaces in fields such as drug discovery and reaction mechanism analysis [14] [15].

This guide objectively compares the performance and applicability of NDDO-based methods—specifically MNDO, AM1, and PM3—against DFT and other computational approaches, with a focus on reaction barrier prediction, a critical parameter in understanding chemical reactivity. We provide experimental data comparing their accuracy, computational efficiency, and limitations, particularly in the context of modern research applications where these methods are increasingly combined with machine learning techniques to achieve DFT-quality results at semi-empirical computation speeds [14] [15].

Theoretical Foundations: The NDDO Framework

Core Approximations and Evolution

All NDDO-based methods belong to the broader class of Zero Differential Overlap (ZDO) methods, but NDDO specifically retains mono-centric differential overlap integrals while neglecting diatomic differential overlap [13]. This theoretical compromise maintains a more physically realistic representation of electron interactions than simpler ZDO methods while remaining computationally tractable. The historical development of these methods reveals a progressive refinement of this core approximation:

Table: Evolution of NDDO-Based Semi-Empirical Methods

| Method | Full Name | Underlying Approximation | Key Innovations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MNDO | Modified Neglect of Diatomic Overlap | NDDO | Original parameterization scheme with 10 parameters per element [13] |

| AM1 | Austin Model 1 | NDDO | Added attractive Gaussian functions to core-core repulsion to improve hydrogen bonding [13] |

| PM3 | Parametric Method 3 | NDDO | Re-parameterized with 13 parameters per element; improved performance for organic molecules [13] |

A critical simplification shared by these methods is the treatment of only valence electrons explicitly in the quantum mechanical treatment, while core electrons combine with nuclei to form an effective core potential [13]. This reduction dramatically decreases the computational complexity compared to methods that treat all electrons explicitly.

Methodological Workflow and Integration with Modern Approaches

The typical application of semi-empirical methods in research follows a structured workflow that leverages their speed while mitigating their accuracy limitations. Recent advances have integrated machine learning as a corrective layer, creating a synergistic approach that maintains the computational advantages of semi-empirical methods while approaching DFT-level accuracy [14].

The diagram below illustrates this integrated workflow for predicting reaction barriers:

Performance Comparison: Semi-Empirical Methods vs. DFT

Accuracy Metrics for Reaction Barriers and Thermochemistry

The performance of semi-empirical methods is typically evaluated by their ability to reproduce experimental data or high-level computational results for key chemical properties. For organic molecules containing C, H, N, and O, the mean unsigned errors for heats of formation demonstrate a clear progression in accuracy across method generations [13]:

Table: Accuracy Comparison of NDDO Methods for Organic Molecules (194 compounds)

| Method | Mean Unsigned Error (kJ/mol) | Mean Signed Error (kJ/mol) | Computational Speed vs. DFT |

|---|---|---|---|

| MNDO | 47.7 | +20.1 | ~10³ faster [14] |

| AM1 | 30.1 | +10.9 | ~10³ faster [14] |

| PM3 | 18.4 | +0.9 | ~10³ faster [14] |

| DFT | N/A | N/A | Reference (Hours-Days) [14] |

| SQM/ML Hybrid | < 4.2 (≈1 kcal/mol) | Minimal | Minutes [14] |

For reaction barrier prediction specifically, the standalone performance of semi-empirical methods is considerably less accurate than DFT, with reported mean absolute errors around 5.71 kcal/mol for nitro-Michael additions [14]. However, when enhanced with machine learning corrections, these errors can be reduced below the chemical accuracy threshold of 1 kcal/mol while maintaining the rapid calculation speed that characterizes semi-empirical methods [14].

Limitations for Specific Elements and Molecular Systems

The performance of semi-empirical methods degrades significantly for certain element types and molecular configurations. Key limitations identified in benchmark studies include:

- Second-row elements: All NDDO methods show "much worse" performance for elements such as sulfur and phosphorus, with hypervalent compounds being particularly problematic [13].

- Nitrogen-containing compounds: AM1 typically predicts inversion barriers that are too low, while PM3 overestimates them, leading to incorrect planar/pyramidal predictions for amide bonds in peptides [13].

- Hydrogen bonding: MNDO performs poorly for hydrogen-bonded systems, a deficiency that AM1 attempted to correct through modified core repulsion functions [13].

- Spin densities and radical systems: Semi-empirical methods show qualitative correctness in predicting spin densities in soot formation simulations but lack quantitative accuracy for thermodynamics and kinetics [16].

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodologies

Standard Validation Approaches for Barrier Prediction

To generate reliable performance comparisons between semi-empirical methods and DFT, researchers typically follow rigorous benchmarking protocols:

Dataset Curation: Diverse sets of molecular systems or reactions are selected to represent the chemical space of interest. For example, in barrier prediction studies, 1000 unique Michael addition reactions were generated using R-group enumeration of α,β-unsaturated carbonyl Michael acceptors with common organic fragments [14].

Geometry Optimization: Structures (reactants, products, and transition states) are optimized using both semi-empirical methods and reference DFT methods. For the Michael addition study, conformational searching was first performed with the OPLS3e force field, followed by optimization with AM1, PM6, and ωB97X-D/def2-TZVP [14].

Energy Calculation: Single-point energy corrections are applied, incorporating solvation effects through continuum solvation models like IEFPCM. For the Michael addition study, this was done with toluene as solvent [14].

Thermochemical Corrections: Free energies are calculated with temperature (298.15 K) and concentration corrections (1 mol L⁻¹) using tools like GoodVibes [14].

Feature Extraction: For machine learning-enhanced approaches, molecular and atomic features are extracted from the semi-empirical calculations, including physical organic chemical descriptors that capture electronic and steric effects [14].

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Semi-Empirical Research

| Tool Name | Function | Implementation in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian | Quantum Chemistry Package | Geometry optimization and single-point energy calculations at multiple levels of theory [14] |

| MOPAC | Semi-Empirical Package | Implementation of PM6, PM7, and other semi-empirical methods with specialized parameter sets [13] |

| Schrödinger's MacroModel | Conformational Search | Generation of low-energy conformers using OPLS3e force field prior to QM optimization [14] |

| GoodVibes | Thermochemical Analysis | Temperature and concentration corrections to calculate quasiharmonic free energies [14] |

| scikit-learn | Machine Learning | Implementation of regression algorithms (Ridge, Random Forest, etc.) for barrier prediction [14] |

Emerging Hybrid Approaches: Machine Learning Enhancement

Synergistic SQM/ML Workflows

The integration of machine learning with semi-empirical quantum mechanical methods represents a paradigm shift in computational chemistry. This synergistic approach leverages the strengths of both methodologies: the physical basis and mechanistic insight from SQM, and the corrective power of ML to bridge the accuracy gap with DFT [14]. The workflow involves:

Rapid SQM Geometry Optimization: Transition state structures are located using semi-empirical methods (AM1, PM6, etc.), providing reasonable approximations of DFT geometries in a fraction of the time [14].

Feature Extraction: Simple, interpretable molecular and atomic features are extracted from the SQM calculations, capturing key electronic and structural properties [14].

ML Barrier Prediction: Machine learning models trained on the relationship between SQM features and DFT barriers predict correction factors, effectively transforming SQM barriers into DFT-quality predictions [14].

This approach has demonstrated remarkable success in predicting DFT-quality free energy activation barriers for C–C bond forming nitro-Michael additions, with mean absolute errors below the chemical accuracy threshold of 1 kcal/mol—a significant improvement over standalone SQM methods (5.71 kcal/mol error) [14].

Next-Generation Hybrid Potentials

Beyond simple ML corrections, true hybrid quantum mechanical/machine learning potentials (QM/Δ-MLPs) are emerging as robust tools for drug discovery applications. These include:

- AIQM1: A hybrid model based on the novel ODMx class of semi-empirical methods with ML corrections, demonstrating robustness for transition state optimizations [15].

- QDπ: A recently developed QM/Δ-MLP that uses DFTB3 as its underlying quantum mechanical method, corrected by a deep-learning potential, showing exceptional accuracy for tautomers and protonation states relevant to drug discovery [15].

These advanced hybrids are particularly valuable for modeling biological systems and drug-like molecules, where they can reliably handle alternative tautomers and protonation states—a significant challenge for conventional molecular mechanics force fields [15].

Semi-empirical methods based on the NDDO approximation, including MNDO, AM1, and PM3, occupy a unique niche in computational chemistry. While their standalone accuracy for reaction barrier prediction lags significantly behind DFT, their computational efficiency—typically three orders of magnitude faster—makes them invaluable for rapid screening and initial mechanistic studies [14]. The performance hierarchy for organic systems is clear: PM3 generally outperforms AM1, which in turn surpasses MNDO for thermochemical properties [13].

The future of these methods lies in their integration with machine learning approaches, creating synergistic frameworks that offer both the speed of semi-empirical calculations and the accuracy of high-level DFT. As hybrid QM/ML potentials continue to mature, they are poised to become universal "force fields" for drug discovery and reaction modeling, capable of reliably handling the complex tautomerism and protonation state chemistry crucial for pharmaceutical applications [15]. For researchers requiring rapid yet accurate barrier predictions, the combined SQM/ML approach represents an unprecedented combination of speed, accuracy, and mechanistic insight that stands to accelerate computational discovery across chemistry and drug development.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) as a Gold Standard for Accuracy

Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as a cornerstone computational method across chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery due to its unique balance of accuracy and computational efficiency. For researchers investigating molecular interactions, reaction barriers, and material properties, DFT provides a critical bridge between highly accurate but expensive wavefunction-based quantum methods and fast but less reliable semi-empirical approaches. The method's versatility allows it to describe diverse systems—from organic molecules and metal complexes to solid-state materials and surfaces—with reasonable computational cost, making it particularly valuable for screening compounds and predicting properties in early-stage research and development.

This guide objectively evaluates DFT's performance against semi-empirical methods, with a specific focus on calculating reaction energy barriers, a property crucial for understanding chemical reactivity and kinetics in catalytic processes and biochemical reactions. We present comparative quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols from recent studies, and essential computational tools to equip researchers with practical knowledge for selecting appropriate methods for their specific applications.

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

Fundamental Principles of DFT

DFT operates on the principle that the ground-state energy of a many-electron system can be uniquely determined by its electron density, rather than the complex many-electron wavefunction. The original Hohenberg-Kohn theorems established the theoretical foundation, while the Kohn-Sham approach introduced a practical computational framework where a fictitious system of non-interacting electrons is constructed to have the same electron density as the real, interacting system. The exact functional relating the energy to the density remains unknown, leading to various approximations for the exchange-correlation functional, which account for quantum mechanical effects not captured by the classical electrostatic terms.

The accuracy of DFT calculations depends critically on the choice of exchange-correlation functional, which can be broadly categorized into Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA), meta-GGA, and hybrid functionals that incorporate exact exchange from Hartree-Fock theory. Each level of sophistication offers different trade-offs between computational cost and accuracy for specific properties like reaction barriers, band gaps, or adsorption energies.

Semi-empirical methods represent a more approximate approach to solving the electronic structure problem by neglecting or parameterizing certain computationally expensive integrals based on experimental data or higher-level calculations. These methods include:

- Extended Hückel Method: A simple, non-self-consistent approach using adjustable parameters for orbital energies and overlap integrals [17] [18]

- DFT-based Tight Binding (DFTB): Derived from a Taylor expansion of the DFT total energy, with parameters precomputed for element pairs [16] [18]

- Parameterized Methods (AM1, PM6, PM7): Based on the Hartree-Fock framework with simplified integrals and extensive parameterization [16]

These methods offer significant computational speed advantages—often 100-1000 times faster than DFT—making them suitable for high-throughput screening, molecular dynamics simulations of large systems, and initial mechanistic studies.

Comparative Accuracy Analysis: DFT vs. Semi-Empirical Methods

Quantitative Performance in Reaction Barrier Prediction

Table 1: Accuracy Comparison for Reaction Barrier Calculations

| Method Category | Specific Method | System/Application | Mean Error vs. High-Level Theory | Computational Cost Relative to DFT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-Empirical | GFN2-xTB | Soot formation pathways [16] | ~13 kcal/mol RMSE | ~0.001x |

| Semi-Empirical | DFTB3 | Soot formation pathways [16] | ~14 kcal/mol RMSE | ~0.001x |

| Semi-Empirical | PM7 | Soot formation pathways [16] | ~25 kcal/mol RMSE | ~0.001x |

| Semi-Empirical | PM6 | Soot formation pathways [16] | ~26 kcal/mol RMSE | ~0.001x |

| Semi-Empirical | AM1 | Soot formation pathways [16] | ~32 kcal/mol RMSE | ~0.001x |

| DFT | HSE06 (hybrid) | Oxide materials formation energies [19] | ~0.15 eV/atom MAD vs. experiment | 10-50x (vs. GGA) |

| DFT | PBE (GGA) | Oxide materials band gaps [19] | ~1.35 eV MAE vs. experiment | 1x (reference) |

| Machine Learning | D-MPNN with 3D features | Organic reaction barriers [20] | ~2-3 kcal/mol MAE | Varies (after training) |

Table 2: Performance for Specific Chemical Systems and Properties

| System Type | Property | Best DFT Performance | Best Semi-Empirical Performance | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissociative chemisorption on metals [21] | Reaction barriers | Chemical accuracy achievable with SRP-DFT for non-charge-transfer systems | Not reliable for quantitative barriers | Fails for charge-transfer systems (E(CT) < 7 eV) |

| 2D materials [17] | Oxygen interaction barriers | Not explicitly reported | XGBoost model trained on EHM data: Good trend prediction | Semi-empirical requires calibration for quantitative accuracy |

| Soot formation precursors [16] | Reaction energies along pathways | M06-2x/def2TZVPP as reference | GFN2-xTB: ~13 kcal/mol RMSE | Semi-empirical methods show large deviations for specific configurations |

| Oxide materials [19] | Formation energies & band gaps | HSE06: 0.62 eV MAE for band gaps | Not typically applicable | Hybrid DFT computationally expensive for high-throughput |

Systematic Error Analysis and Limitations

The comparative data reveals distinct patterns in the performance characteristics of DFT and semi-empirical methods. DFT generally provides more accurate and transferable results across diverse chemical systems, with hybrid functionals like HSE06 offering significant improvements for electronic properties at increased computational cost. However, DFT faces particular challenges with specific chemical systems, such as dissociative chemisorption reactions prone to electron transfer, where standard functionals fail to describe the complex electronic structure changes accurately [21].

Semi-empirical methods demonstrate substantially larger errors that vary significantly between method parameterizations and chemical systems. While GFN2-xTB and DFTB3 show the best overall performance among semi-empirical approaches for reaction energies, their errors of ~13-14 kcal/mol far exceed the ~1-2 kcal/mol chemical accuracy threshold required for quantitative predictive simulations. Critically, these methods often fail to provide systematically improvable results, as their parameterizations may be optimized for specific chemical environments but perform poorly for others.

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodologies

Benchmarking Dissociative Chemisorption on Metal Surfaces

The accurate determination of reaction barriers for dissociative chemisorption represents a significant challenge for computational methods. The state-of-the-art protocol employs a semi-empirical DFT approach called Specific Reaction Parameter DFT (SRP-DFT):

- Functional Selection: A density functional with a single adjustable parameter is selected, typically based on the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) [21]

- Parameter Optimization: The functional parameter is adjusted to reproduce experimental dissociative chemisorption probabilities measured as a function of translational incidence energy in supersonic molecular beam experiments [21]

- Dynamics Calculations: Quantum or classical dynamics calculations are performed on potential energy surfaces generated with the optimized functional to extract accurate barrier heights [21]

- Validation: The method's transferability is tested by comparing calculated and experimental results across different reaction conditions

This approach has successfully produced chemically accurate barrier heights for 14 molecule-metal surface systems, creating a valuable benchmark database for evaluating new density functionals [21].

High-Throughput Screening of 2D Materials

A combined semi-empirical and machine learning approach has been developed for high-throughput screening of oxygen interaction barriers on 4036 two-dimensional materials:

- Semi-Empirical Calibration: The Extended Hückel Method (EHM) is calibrated to reproduce known oxygen barriers on graphene as a reference system [17]

- Barrier Calculation: Oxygen migration barriers are computed along multiple adsorption paths using the calibrated EHM approach [17]

- Descriptor Computation: Material descriptors are extracted from the Computational 2D Materials Database (C2DB) and Matminer [17]

- Machine Learning Model Training: Supervised learning models (XGBoost performed best) are trained to predict barrier heights from descriptors [17]

- Model Interpretation: SHAP analysis identifies key electronic features (electronegativity, valence electron count) as primary predictors of barrier height [17]

This workflow enables efficient screening of oxidation resistance in 2D materials while maintaining physical interpretability through the machine learning model.

Accuracy Validation for Molecular Datasets

Recent research has established rigorous protocols for validating the numerical accuracy of DFT calculations in large molecular datasets:

- Net Force Analysis: The vector sum of force components on all atoms is computed—nonzero values indicate numerical errors in the DFT calculation [22]

- Force Component Comparison: Individual force components are recomputed using tightly converged DFT settings with the same functional and basis set [22]

- Error Quantification: Root-mean-square errors between original and recomputed forces are calculated to quantify numerical uncertainties [22]

- Threshold Application: Structures with net forces exceeding 1 meV/Å per atom are flagged as potentially problematic for machine learning potential training [22]

This approach revealed significant force errors in several popular DFT datasets (ANI-1x: ~33 meV/Å, Transition1x: ~8 meV/Å), highlighting the importance of well-converged computational settings for generating reliable reference data [22].

Workflow Visualization: Computational Method Selection

Table 3: Key Software and Database Solutions for Computational Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| FHI-aims [19] | All-electron DFT Code | High-accuracy electronic structure with NAO basis sets | Materials database generation with hybrid functionals |

| QuantumATK [18] | Multi-method Platform | Semi-empirical and DFT calculations for materials/nanodevices | Electronic transport, surface chemistry |

| ORCA [22] | Quantum Chemistry Package | DFT, wavefunction methods, semi-empirical calculations | Molecular spectroscopy, reaction mechanisms |

| C2DB [17] | Materials Database | Curated 2D materials properties | High-throughput screening of 2D materials |

| Open Molecules 2025 [23] | DFT Dataset | >100M ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD calculations | Training machine learning interatomic potentials |

| ChemTorch [20] | Machine Learning Framework | Graph neural networks for chemical property prediction | Reaction barrier prediction from 2D structures |

| Materials Project [19] | Materials Database | DFT-calculated properties of inorganic compounds | Materials discovery and design |

DFT maintains its position as the gold standard for accuracy in computational chemistry, particularly for reaction barrier predictions where its systematic improvability and transferability across chemical systems outperform semi-empirical approaches. The method's robustness stems from its firm theoretical foundation and continuous development of improved exchange-correlation functionals. Nevertheless, semi-empirical methods retain significant value for high-throughput screening, large-system dynamics, and initial mechanistic studies where their computational efficiency enables investigations impractical with DFT.

Future methodological developments will likely focus on hybrid approaches that leverage the respective strengths of both methodologies. Machine learning models trained on high-quality DFT data show particular promise for achieving DFT-level accuracy at significantly reduced computational cost [20]. Meanwhile, ongoing efforts to develop more universally accurate density functionals and address known limitations in specific chemical systems will further solidify DFT's role as the foundational method for computational molecular sciences.

In biochemistry, the accurate prediction of reaction barrier heights, or activation energies, is fundamental to understanding and controlling enzymatic reactions, drug metabolism, and molecular signaling pathways. These barriers determine reaction rates and selectivity through the Arrhenius equation, directly influencing biological outcomes from neurotransmitter kinetics to prodrug activation. Computational chemistry provides essential tools for quantifying these barriers, with semi-empirical quantum mechanical (SQM) methods and density functional theory (DFT) representing two primary approaches with distinct trade-offs in accuracy and computational cost. This guide objectively compares their performance for barrier calculation in biochemical research contexts, providing experimental data and methodologies to inform researchers' selection criteria.

Performance Comparison: Semi-Empirical vs. DFT Methods

Extensive benchmarking studies reveal significant performance differences between computational methods for reaction barrier prediction. The table below summarizes quantitative accuracy data from key studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Computational Methods for Barrier Height Prediction

| Method Category | Specific Method | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Computational Cost | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-Empirical | GFN2-xTB | ~5 kcal/mol (vs. DFT) [4] | Very Low | High-throughput screening, large systems |

| Semi-Empirical | PM6/PM7 | 5.71 kcal/mol (vs. DFT) [14] | Very Low | Preliminary mechanism exploration |

| DFT | ωB97X-D3/def2-TZVP | ~5 kcal/mol (vs. CCSD(T)) [24] | High | Final accurate barrier determination |

| High-Level Ab Initio | CCSD(T)-F12a | Reference method [24] | Very High | Benchmark quality data |

| Machine Learning | SQM/ML Hybrid | <1 kcal/mol (vs. DFT) [14] | Low (after training) | Rapid prediction with DFT-level accuracy |

The data demonstrates that while SQM methods offer speed advantages, their accuracy limitations necessitate careful application. The 5-6 kcal/mol errors typical of SQM methods can lead to rate prediction errors of several orders of magnitude at room temperature, which is often unacceptable for precise biochemical predictions [4] [14]. DFT methods provide better accuracy but remain about 5 kcal/mol less accurate than the gold-standard CCSD(T) methods [24].

Methodological Frameworks for Barrier Prediction

Standard Protocol for DFT Barrier Calculations

For publication-quality results, researchers employ rigorous DFT protocols:

Geometry Optimization: First, optimize reactant and transition state structures using a functional like B3LYP with dispersion corrections (D3/D4) and a basis set such as DEF2-SVP [25].

Frequency Analysis: Confirm reactants as true minima (no imaginary frequencies) and transition states with exactly one imaginary frequency [25].

Energy Refinement: Perform single-point energy calculations on optimized geometries using higher-level methods, potentially including:

Barrier Calculation: Compute ΔG‡ = G°TS - G°reactants [25]

This protocol balances computational cost with accuracy, though the coupled-cluster refinement significantly increases resource requirements.

Emerging Machine Learning Approaches

Recent advances combine the speed of SQM with ML correction to achieve DFT-level accuracy. One validated workflow includes:

- Generate transition state geometries using SQM methods (AM1 or PM6) [14]

- Extract physical-organic descriptors from SQM calculations (atomic charges, bond orders, orbital properties) [14]

- Apply ML models (ridge regression, random forest, or neural networks) trained on DFT benchmarks to predict corrected barriers [14]

- Validate predictions on external test sets to ensure generalizability [14]

This approach achieves chemical accuracy (<1 kcal/mol MAE) while reducing computation time from days to minutes, enabling high-throughput screening of enzymatic reactions or drug metabolism pathways [14].

Visualization: Computational Workflows for Barrier Prediction

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Barrier Prediction

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORCA [25] | Quantum Chemistry Software | DFT, coupled-cluster, SQM calculations | High-accuracy barrier computation for reaction mechanisms |

| Gaussian [14] | Quantum Chemistry Software | DFT, SQM, frequency calculations | Thermodynamic property calculation with solvation models |

| GFN2-xTB [4] | Semi-Empirical Method | Fast geometry optimization and energy calculation | Large system screening (e.g., protein-ligand interactions) |

| DLPNO-CCSD(T) [25] | High-Level Ab Initio Method | Benchmark-quality single-point energies | Reference data generation for ML training or validation |

| ChemTorch [20] [26] | Machine Learning Framework | Barrier prediction with graph neural networks | Rapid screening of reaction libraries |

| GoodVibes [14] | Computational Analysis Tool | Thermochemical correction processing | Calculating concentration-corrected free energies |

The critical need for accurate reaction barrier prediction in biochemistry continues to drive methodological innovations. While DFT remains the standard for reliable barrier heights, its computational expense limits application to high-value targets. Semi-empirical methods offer unparalleled speed but require ML correction or DFT validation for quantitatively accurate predictions. Emerging hybrid SQM/ML approaches represent a promising middle ground, offering DFT-level accuracy at significantly reduced computational cost [14].

For research applications requiring the highest accuracy on small systems, DFT with coupled-cluster refinement provides benchmark-quality results. For high-throughput virtual screening of drug metabolism pathways or enzymatic reactions, ML-corrected SQM methods now offer a viable alternative. Future directions include improved integration of 3D structural information through graph neural networks [20] [26] and continued expansion of high-quality training datasets like those generated by CCSD(T)-F12a calculations [24].

A Practical Toolkit: Key Semi-Empirical Methods and Their Use in Biomolecular Modeling

Semi-empirical quantum mechanical methods occupy a crucial niche in computational chemistry, providing a balance between computational cost and accuracy that is essential for studying large molecular systems. These methods are approximately 2 to 3 orders of magnitude faster than standard Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations while still providing quantum mechanical treatment of electrons, making them indispensable for exploring potential energy surfaces, conducting molecular dynamics simulations, and treating systems with hundreds to thousands of atoms [27] [1]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of four popular semi-empirical methods—PM3, AM1, PM7, and Density-Functional Tight-Binding (DFTB)—focusing on their theoretical foundations, performance characteristics, and practical applications in computational research, particularly in the context of barrier calculation studies and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Evolution

Historical Development of NDDO-Based Methods

The Neglect of Diatomic Differential Overlap (NDDO) family of semi-empirical methods includes PM3, AM1, and PM7. These methods originated from the pioneering work of Pople, Dewar, and Thiel, who developed approximations to reduce computational complexity while maintaining quantum mechanical accuracy [28]. The fundamental approximation involves neglecting diatomic differential overlap, which dramatically reduces the number of electron repulsion integrals that must be computed [15].

AM1 (Austin Model 1) was developed as an improvement over the earlier MNDO method, with modified core-core repulsion functions that better reproduced hydrogen bonding interactions [27] [15]. PM3 (Parametric Method 3) followed, using similar formalism but with parameters optimized against a larger set of experimental data [27]. The most recent iteration, PM7, incorporates additional constraints and corrections based on extensive testing against experimental and high-level ab initio reference data, including better treatment of noncovalent interactions and correction of previously identified formalism errors [28].

Density-Functional Tight-Binding (DFTB) Formalism

DFTB takes a different approach, being derived from Density Functional Theory rather than Hartree-Fock theory. The method expands the DFT total energy in a Taylor series around a reference density constructed from neutral atomic densities [1]. Different orders of expansion lead to different DFTB variants:

- DFTB0 (or NCC-DFTB): The non-self-consistent charge method, representing the zeroth-order expansion [27]

- DFTB2 (SCC-DFTB): Includes second-order terms with self-consistent charge corrections [1]

- DFTB3: Extends to third-order expansion, providing improved treatment of charge transfer and chemical reactivity [1] [29]

DFTB methods use precomputed parameter sets derived from DFT calculations, with integrals tabulated for efficient computation [27] [1]. The computational efficiency of DFTB is similar to NDDO-based methods, being approximately 100-1000 times faster than DFT with medium-sized basis sets [1].

Table 1: Theoretical Foundations of Semi-Empirical Methods

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Key Features | Parameterization Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| AM1 | NDDO approximation | Modified core-core repulsion vs MNDO; improved hydrogen bonding | Fitted to experimental molecular properties |

| PM3 | NDDO approximation | Similar formalism to AM1; different parameter set | Optimized against larger experimental dataset |

| PM7 | NDDO approximation with corrections | Improved noncovalent interactions; corrected formalism errors | Fitted to experimental and high-level ab initio data including solids |

| DFTB | DFT-based tight-binding | Expansion of DFT energy; tabulated integrals | Parameters from DFT calculations; some empirical fitting |

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking

Geometries and Energetics of Organic Molecules

Comprehensive benchmarking studies reveal significant differences in the performance of semi-empirical methods for predicting molecular geometries and energies. In a landmark study comparing methods for C20–C86 fullerene isomers, the SCC-DFTB method outperformed PM3 and AM1 for geometry predictions, with RMS deviations from B3LYP/6-31G(d) geometries of 0.019 Å for SCC-DFTB, compared to 0.030 Å for PM3 and 0.035 Å for AM1 [27]. For relative energies of fullerene isomers, SCC-DFTB also showed better correlation with DFT results than the NDDO-based methods [27].

For organic molecules containing C, H, N, O elements, PM7 generally demonstrates improved accuracy over its predecessors. In benchmark studies across diverse molecular sets, PM7 reduced the average unsigned error (AUE) in bond lengths by about 5% and in heats of formation by about 10% compared to PM6 [28]. For organic solids, the improvement was even more substantial, with AUE in ΔHf dropping by 60% and geometric errors reduced by 33.3% [28].

Reaction Barrier Heights

Accurate prediction of reaction barriers is crucial for studying chemical reactivity, and this represents a significant challenge for semi-empirical methods. The development of PM7 brought notable improvements in this area. For a set of simple organic reactions, PM7 achieved an AUE in barrier heights of 10.8 kcal/mol, improved from 12.6 kcal/mol with PM6 [28]. Further refinement using a two-step process (PM7-TS) reduced this error to 3.8 kcal/mol, approaching chemical accuracy (1 kcal/mol) for these systems [28].

DFTB methods have shown variable performance for barrier predictions. Recent approaches combining DFTB with machine learning corrections have demonstrated remarkable accuracy, achieving mean absolute errors below 1 kcal/mol for C–C bond forming nitro-Michael addition reactions, while maintaining the computational efficiency of the underlying semi-empirical method [30].

Non-Covalent Interactions and Biological Applications

Non-covalent interactions, including hydrogen bonding, dispersion, and π-stacking, are crucial for biological and pharmaceutical applications. PM7 includes specific hydrogen-bond corrections that make it particularly accurate for hydrogen-bonded complexes [31]. DFTB methods, while generally reasonable for various biological systems, have been shown to underestimate hydrogen bonding interactions and torsional barriers in certain contexts, such as sugar chemistry [29].

For drug discovery applications, modern semi-empirical methods show promise as universal force fields capable of modeling alternative tautomers and protonation states, which are essential for ~30% of drug-like molecules that can exist as multiple tautomers [15]. In comprehensive benchmarking, the OMx methods (which include orthogonalization corrections) generally show the best overall performance for organic molecules, but PM7 remains a valuable alternative, especially for elements beyond C, H, N, O, F [31].

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Methodologies

| Property | PM3 | AM1 | PM7 | DFTB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Length Accuracy (RMSD vs DFT) | ~0.030 Å [27] | ~0.035 Å [27] | ~5% improvement over PM6 [28] | ~0.019 Å (SCC-DFTB) [27] |

| Heat of Formation AUE | Higher than PM7 [28] | Higher than PM7 [28] | ~10% improvement over PM6 [28] | Varies by parameterization |

| Reaction Barrier AUE | ~12.6 kcal/mol (PM6) [28] | Similar to PM3 | 10.8 kcal/mol (3.8 with TS protocol) [28] | Can reach <1 kcal/mol with ML correction [30] |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Moderate accuracy | Moderate accuracy | Good (explicit corrections) [31] | Tendency to underestimate [29] |

| Computational Speed | ~100-1000x faster than DFT [1] | ~100-1000x faster than DFT [1] | ~100-1000x faster than DFT [1] | ~100-1000x faster than DFT [1] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Assessment Protocols

Benchmarking studies typically follow rigorous protocols to ensure fair comparison between methods. Geometry optimization is performed starting from consistent initial structures, with convergence criteria typically set to 2×10^-6 au for the gradient [29]. Frequency calculations confirm local minima and provide thermodynamic properties. Single-point energy calculations at higher levels of theory (e.g., G3B3, CCSD(T)) on optimized geometries allow evaluation of energetic properties [29].

For performance assessment, several benchmark datasets have been established:

- GMTKN24/30: Comprehensive collections for general main-group thermochemistry, kinetics, and noncovalent interactions [1] [31]

- W4-11: High-confidence atomization energies [31]

- S30L: Large noncovalent complexes [31]

- AEGIS: Natural and synthetic nucleic acids with diverse tautomers and protonation states [15]

Specialized Protocols for Reaction Barriers

Accurate assessment of reaction barriers requires precise transition state optimization. The PM7-TS protocol involves a two-step process: initial transition state optimization at the PM7 level followed by single-point energy calculation using a specialized parameter set [28]. This approach reduced errors in barrier heights from 10.8 kcal/mol to 3.8 kcal/mol for a set of organic reactions [28].

Recent hybrid approaches combine semi-empirical methods with machine learning. For example, in the study of nitro-Michael additions, SCC-DFTB transition state structures were first generated, then machine learning models applied to predict DFT-quality barriers, achieving chemical accuracy (<1 kcal/mol error) while maintaining the computational efficiency of DFTB [30].

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Semi-Empirical Calculations

| Software Package | Methods Implemented | Key Features | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOPAC | PM3, AM1, PM6, PM7 | Specialized for semi-empirical methods; active development | Geometry optimization; reaction modeling |

| GAMESS | DFTB, AM1, PM3, PM6 | Broad quantum chemistry capabilities; QM/MM support | Large-scale calculations; enzymatic reactions |

| Gaussian | AM1, PM3, PM6, PM7 | User-friendly interface; extensive method range | Spectroscopy; reaction mechanisms |

| DFTB+ | DFTB0, DFTB2, DFTB3 | Specialized for DFTB methods; extended parameter sets | Materials science; nanoscale systems |

| AMBER | DFTB, AM1, PM3 (SQM) | Integration with molecular dynamics | Biomolecular simulations; QM/MM |

Method Selection Framework

The choice of semi-empirical method depends critically on the specific application and chemical system. The following decision diagram illustrates a systematic approach to method selection:

Semi-empirical quantum chemical methods provide an essential bridge between highly accurate but computationally expensive ab initio methods and efficient but limited molecular mechanics approaches. For geometry predictions of organic molecules, SCC-DFTB and PM7 generally show superior performance, while for reaction barriers, PM7 with specialized protocols or DFTB with machine learning corrections can approach chemical accuracy. The continued development of these methods, particularly through integration with machine learning approaches and improved parameterization, promises to further expand their utility in drug discovery, materials science, and mechanistic studies where both computational efficiency and quantum mechanical accuracy are essential.

Semi-empirical quantum chemical (SQC) methods occupy a crucial niche in computational chemistry, providing a balance between computational cost and electronic structure detail that sits between molecular mechanics and ab initio methods. [32] [33] The neglect of diatomic differential overlap (NDDO) family of methods, which includes PM7, achieves computational speeds several orders of magnitude faster than typical density functional theory (DFT) calculations by using minimal basis sets and empirically parameterized integrals. [14] [33] This efficiency enables the modeling of large systems, such as biomacromolecules and solids, but traditionally at the cost of accuracy, particularly for noncovalent interactions which are crucial in biological and materials systems. [34] [33]

The PM7 method, released in 2013, was developed specifically to address systematic failures of its predecessor, PM6, by incorporating a broader range of reference data, including experimental and high-level ab initio data for solids and noncovalent complexes. [32] This guide provides an objective performance comparison of PM7 against other SQC and DFT methods, focusing on its enhanced capabilities for noncovalent interactions and solid-state systems, contextualized within the broader evaluation of SQC methods for reaction barrier calculations.

Core Theoretical Enhancements in PM7

The development of PM7 introduced specific modifications to the NDDO approximations to rectify known physical shortcomings in PM6, particularly those manifesting in extended systems.

Modification of Core-Core Repulsion

In conventional NDDO methods, the core-core interaction term γAB was found to converge to the exact point-charge value at different rates for different atom pairs. While negligible for molecular calculations, this inconsistency produces infinite errors in the electrostatic sums of crystalline solids. [32] PM7 addresses this by enforcing a smooth transition to the exact 1/R point-charge limit for all atom pairs at a distance of 7.0 Å, ensuring no net attraction or repulsion between neutral atoms at large separations and making the method suitable for periodic systems. [32]

Empirical Corrections for Noncovalent Interactions

Noncovalent interactions like hydrogen bonding and dispersion are poorly described by the underlying Hartree-Fock theory and minimal basis sets used in NDDO methods. [33] While earlier corrections like PM6-D3H4 added empirical post-SCF terms for dispersion (D3) and hydrogen bonding (H4), [34] [35] PM7 integrates these considerations directly into its parameterization. [32] [34] This was achieved by using reference data sets containing various noncovalent complexes during the parameter optimization process itself. [34]

Performance Evaluation: PM7 vs. Alternatives

The accuracy of PM7 is best understood by comparing its performance against other semi-empirical methods and DFT across key chemical properties. The following tables summarize quantitative benchmarks from various studies.

Accuracy for Noncovalent Interactions

Noncovalent interactions are a critical test for any method applied to biological systems. Benchmarking against high-level CCSD(T)/CBS reference data reveals the performance of various methods. [34] [35]

Table 1: Performance on Noncovalent Interaction Energies (RMSE from reference, kcal/mol)

| Method | S22×5 Set (Various Complexes) | S66×8 Set (Various Complexes) | X31×10 Set (Halogenated) | Ionic Set (Charged H-Bonds) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM6 | 3.34 | 2.90 | 2.21 | 5.82 |

| PM6-D3H4 | 1.21 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 2.34 |

| PM7 | 1.16 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 2.16 |

| DFT (ωB97X-D) | ~0.6 | <1.0 (across various DFT-D) | <1.0 (across various DFT-D) | <1.0 (across various DFT-D) |

PM7 shows a dramatic improvement over PM6, reducing the root-mean-square error (RMSE) by about 65-85% across different benchmark sets. [34] Its performance is comparable to the empirically corrected PM6-D3H4 and approaches the accuracy of well-corrected DFT functionals like ωB97X-D for many interaction types. [35] However, PM7's performance is not uniform; it can show relatively larger errors for pure dispersion-bound complexes and water clusters. [34]

General Chemical Accuracy and Proton Transfers

For general chemical properties and reactions, PM7 also represents a significant step forward.

Table 2: Performance on General Chemical Properties

| Property | Method | Performance (Error Relative to Reference) |

|---|---|---|

| ΔHƒ (Organic Molecules) | PM6 | Baseline |

| PM7 | ~10% reduction in Average Unsigned Error (AUE) [32] | |

| Geometry (Bond Lengths) | PM6 | Baseline |

| PM7 | ~5% reduction in AUE [32] | |

| Reaction Barrier Heights | PM6 | AUE = 12.6 kcal/mol [32] |

| PM7 | AUE = 10.8 kcal/mol [32] | |

| PM7-TS (2-step) | AUE = 3.8 kcal/mol [32] | |

| Proton Transfer Reaction Energies | PM7 | Mean Unsigned Error (MUE) = 13.4 kJ/mol (3.2 kcal/mol) [36] |

| PM6 | MUE = 20.3 kJ/mol (4.9 kcal/mol) [36] | |

| GFN2-xTB | MUE = 13.5 kJ/mol (3.2 kcal/mol) [36] | |

| B3LYP/def2-TZVP | MUE = ~7.3 kJ/mol (1.7 kcal/mol) [36] |

For proton transfers, PM7 is among the most accurate SQC methods, outperforming PM6 and matching the modern GFN2-xTB method. [36] However, it is still less accurate than standard DFT functionals. A notable development is the PM7-TS two-step protocol, which drastically improves the prediction of activation barriers, bringing them to within chemical accuracy (1 kcal/mol) for simple organic reactions. [32]

Performance on Solids and Liquid Water

A key aim of PM7 was to improve the modeling of condensed phases. For organic solids, PM7 reduces the AUE in heats of formation by 60% and in geometries by 33.3% compared to PM6. [32] However, describing the complex hydrogen-bond network of liquid water remains a significant challenge for all SQC methods with their original parameters. [37] Standard PM7 and PM6 both suffer from too weak hydrogen bonding, predicting a "far too fluid" water structure. [37] This limitation can be overcome by specific re-parameterization, as demonstrated by the PM6-fm (force-matched) method, which quantitatively reproduces the structure and dynamics of liquid water. [37]

Experimental and Computational Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, this section outlines the standard methodologies used for benchmarking in the cited studies.

Benchmarking Noncovalent Interactions

The standard protocol for evaluating noncovalent interactions involves several key steps to ensure reliable and comparable results. [34] [35]

- Reference Data Sets: Use established benchmark sets like S22, S66, and X31 from the Benchmark Energy and Geometry Database (BEGDB). These sets include complexes categorized as hydrogen-bonded, dispersion-dominated, and mixed, at both equilibrium and non-equilibrium geometries. [35]

- Reference Method: Use interaction energies calculated at the CCSD(T)/CBS (coupled-cluster singles, doubles, and perturbative triples with complete basis set extrapolation) level, considered the "gold standard," as the reference. [35]

- Procedure: For each method under test (e.g., PM7, PM6-D3H4), the dimer interaction energy is computed as the difference between the energy of the complex and the sum of the energies of the isolated monomers:

E_int = E_AB - (E_A + E_B). Geometry optimization of the complex is typically performed at the same level of theory before the single-point energy calculation. [34] [35] - Analysis: The computed interaction energies are compared against the CCSD(T)/CBS references, and statistical errors (RMSE, MAE) are reported for each method and data set. [34] [35]

The PM7-TS Protocol for Reaction Barriers

The PM7-TS protocol is a two-step procedure designed to achieve DFT-quality barrier heights at SQC cost. [32]