Solvent Compatibility in Automated Liquid Handling: A Complete Guide for Robust Research and Drug Development

This comprehensive guide addresses the critical challenge of solvent compatibility in automated liquid handling systems, a pivotal factor for data integrity, operational efficiency, and instrument longevity in biomedical research and...

Solvent Compatibility in Automated Liquid Handling: A Complete Guide for Robust Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This comprehensive guide addresses the critical challenge of solvent compatibility in automated liquid handling systems, a pivotal factor for data integrity, operational efficiency, and instrument longevity in biomedical research and drug development. Covering foundational principles to advanced troubleshooting, it equips scientists with the knowledge to select compatible materials, develop robust methods, optimize liquid classes for challenging solvents like DMSO and glycerol, and validate system performance. By synthesizing current best practices and technical insights, this article provides a strategic framework to prevent costly errors, enhance reproducibility, and accelerate high-throughput discovery workflows.

Why Solvent Compatibility Matters: Core Principles and Impact on Data Integrity

FAQs: Understanding Solvent Compatibility

What is solvent compatibility and why is it more than just chemical resistance? Solvent compatibility is the ability of a material to withstand exposure to a chemical solvent without suffering adverse effects that could impact an experiment or instrument. It goes beyond simple chemical resistance, which often only considers immediate, gross failure like dissolution or cracking. A fully compatible material will not degrade, swell, discolor, or leach compounds, and will maintain its mechanical and functional integrity over the application's required lifespan and under specific operating conditions such as elevated temperature [1] [2].

Why do two solvents with similar polarity sometimes behave differently with the same component? While polarity is a useful guide, other physicochemical properties of a solvent can lead to different interactions. Factors such as surface tension, volatility, and hydrogen bonding can influence behaviors like "filming" - where a thin residual layer of solvent wicks down and drips from a pipette tip - or the formation of micro-droplets. These properties, combined with environmental factors like static charge, mean that two solvents with similar polarity can require different handling parameters on an automated liquid handler [3].

How do operating conditions like temperature affect solvent compatibility? Temperature can significantly alter compatibility. A material rated as "Excellent" for containing a detergent at 22°C (standard room temperature) may see its compatibility diminish at 37°C, a common temperature for cell culture experiments. Higher temperatures can accelerate chemical degradation, increase the permeability of polymers, and exacerbate swelling. Always consult compatibility charts at your specific operating temperature and consider alternatives like ceramics for heated applications [1].

My chemical is compatible with SS 316. Can I use the cheaper SS 304 instead? No, the specific material grade is critical. For instance, Stainless Steel 316 contains about 2% molybdenum, which specifically increases its resistance to salts commonly found in biochemical buffers. Stainless Steel 304, which lacks molybdenum, has a lower compatibility rating with these salts and could lead to corrosion and instrument failure. When consulting compatibility charts, ensure you are assessing the exact material specified for your components [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Liquid Handling Precision with Aggressive Solvents

Symptoms: Inaccurate dispensing volumes, dripping tips, visible swelling or corrosion of fluid path components, or hazy/discolored solvents indicating leaching.

Investigation and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Rationale & Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Identify | Confirm the exact chemical name, concentration, and mixture of all solvents and samples [1]. | Chemical compatibility is concentration-dependent. A manifold may tolerate 20% sodium hydroxide but fail with an 80% concentration [1]. |

| 2. Consult | Use a chemical compatibility guide (e.g., Cole-Parmer Database). Cross-reference your solvent with the exact material of your fluid path [1]. | These charts provide ratings from "Excellent" (no interaction) to "Severe" (material failure). They are a essential first guide, though they may not cover all conditions [1]. |

| 3. Select | Choose the component material that offers the least deleterious effects your application can tolerate. | If no perfect material exists, prioritize tolerable effects (e.g., slight discoloration) over catastrophic ones (e.g., severe pitting and corrosion from bleach on PEEK) [1]. |

| 4. Test | Perform a Solvent Compatibility Test on a sample of the component or a finished device [4]. | This practical test reveals real-world interactions under your specific conditions. The methodology is outlined in the experimental protocol below. |

Problem: Static Charge Disrupting Low-Volume Solvent Transfers

Symptoms: Unpredictable, intermittent droplet formation or misdirection, particularly with volumes below 20 µL.

Investigation and Resolution:

- Measure Static: Use a static meter (e.g., KEYENCE) to identify locations of charge buildup on the instrument deck. Readings above 2 kilovolts have the potential to disrupt transfers [3].

- Install Ionization Bars: Install ionization bars on the liquid handler to neutralize static charge. Some systems can use positive pressure nitrogen to help distribute the ions across the deck [3].

- Adjust Method Parameters: Incorporate strategic pauses after dispense cycles to allow micro-droplets to settle and consider adjusting dispense speeds to minimize static generation [3].

Experimental Protocol: Solvent Compatibility Testing

This protocol provides a methodology to empirically determine the compatibility between a solvent and a device material, as referenced in the troubleshooting guide [4].

Objective: To evaluate the physical and chemical changes in a device material after exposure to a solvent.

Materials:

- Device or material sample (as close to the final product as possible)

- Selected solvents (at least one polar and one non-polar)

- Clean, clear glass jars with lids (e.g., jam jars)

- Measuring cylinder

- Warm location or incubator (e.g., 37°C, 50°C)

- pH indicator strips or pH meter

- (Optional) Household substitutes for testing: nail polish remover (for acetone), vegetable oil (for cottonseed oil), saltwater (for saline) [4]

Procedure:

- Device Preparation: Disassemble the device if necessary. Cut or section the materials to fit the jars, noting any difficulties like brittleness or crumbling. Record the initial appearance [4].

- Solvent Selection: Choose appropriate solvents. Common choices for screening are acetone (polar), hexane (non-polar), and water (aqueous) [4].

- Exposure:

- Place the prepared material pieces into individual glass jars.

- Add a measured amount of each solvent, enough to fully submerge the pieces but not so much that a color change would be diluted.

- Cover the jars to prevent evaporation.

- Place them in a warm location (e.g., 37°C) for a minimum of one minute, though several days is typical. Agitate the containers periodically if possible [4].

- Post-Extraction Evaluation: After the exposure period, examine both the solvent and the device material for changes [4]:

- Solvent: Check for color change, sediments/precipitates, opacity change, and pH change.

- Device Material: Check for softening, swelling/shrinking, debris, dissolution, or color change.

- Measure the total volume of liquid to estimate solvent absorption.

Interpretation: Any observed changes indicate an interaction. Discuss these results with your testing lab to determine acceptability, select alternative solvents, or design mitigation strategies like post-extraction filtration [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Solvent Compatibility Management

| Item | Function & Technical Specificity |

|---|---|

| PEEK (Polyetheretherketone) | A high-performance polymer with excellent chemical resistance to a wide range of organic and inorganic chemicals, making it suitable for pumps, valves, and manifolds. Incompatible with strong acids like nitric and sulfuric acid, and susceptible to stress cracking with certain solvents [1]. |

| PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene) | Known for its exceptional non-stick properties and broad chemical inertness. It is highly resistant to aggressive solvents and is often used for seals, tubing, and fluid paths in liquid handling systems [1]. |

| Stainless Steel 316 | A corrosion-resistant metal alloy containing molybdenum, which provides enhanced resistance to salts and chlorides. Preferred over SS 304 for biochemical applications involving buffering solutions [1]. |

| Ceramic Components | Used for applications involving detergents and other reagents at elevated temperatures (e.g., above 22°C) where metal compatibility may diminish. Offers excellent thermal and chemical stability [1]. |

| HPLC Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents specifically purified to eliminate UV-absorbing impurities, ensuring they do not interfere with sensitive analytical detection methods like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography [5]. |

| Chemical Compatibility Database | An online resource (e.g., Cole-Parmer) that allows researchers to cross-reference chemicals with construction materials to get a compatibility rating, serving as a critical first step in material selection [1]. |

Workflow Diagrams

In automated liquid handling research, the physical properties of solvents—primarily viscosity, surface tension, and vapor pressure—are not merely characteristics but critical determinants of experimental success. These properties directly dictate the behavior of liquids during aspiration and dispensing, influencing the accuracy, precision, and reproducibility of protocols [6]. Automated systems rely on precise "liquid classes," which are sets of parameters that translate a solvent's physical properties into mechanical commands for the pipetting system [6]. A failure to correctly account for these properties can lead to a cascade of issues, from volume inaccuracies and cross-contamination to the complete failure of a high-throughput screening assay. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and foundational knowledge to help researchers navigate these challenges effectively.

Troubleshooting Common Solvent Handling Issues

Q1: My dispensed volumes for viscous glycerol solutions are consistently too low. What should I check?

- Problem: Inaccurate dispensing of viscous liquids.

- Solutions:

- Adjust Liquid Class Parameters: Significantly reduce the aspiration and dispensing speeds within your liquid class. This gives the resistant fluid time to move fully into and out of the tip. Also, increase the delay times after aspiration and before dispensing to allow for fluid settlement [6] [7].

- Change Pipetting Technique: Switch from forward pipetting to reverse pipetting. This technique involves aspirating extra liquid and then dispensing only the desired volume, which compensates for the film of liquid that adheres to the tip wall [7] [8].

- Use Specialized Hardware: For highly viscous liquids, consider switching to a positive displacement pipetting system. This method uses a piston that contacts the liquid directly, eliminating the compressible air cushion that causes inaccuracies with viscous samples in air displacement systems [6] [7].

Q2: I notice droplets of my DMSO solution clinging to the outside of the tip and dripping. How can I prevent this?

- Problem: Dripping from the tip due to low surface tension and high vapor pressure.

- Solutions:

- Optimize for Volatility: For solvents like DMSO, methanol, or acetone, your liquid class should include a slower aspiration speed to reduce turbulence and bubble formation, and an air gap after aspiration to create a buffer against dripping [6] [9].

- Use a Touch-Off Action: Employ a wet dispense or "touch-off" strategy. After dispensing, the tip touches the side of the well, using surface tension to wick away the residual droplet and ensure a clean release [6].

- Tip Selection: Use low-retention tips that are specifically treated to reduce liquid adhesion, helping droplets release more completely [7].

Q3: My aqueous buffer with detergent is forming bubbles and leading to volume inaccuracies. What is the cause?

- Problem: Bubble formation in solutions with low surface tension.

- Solutions:

- Modify Liquid Class: Reduce the aspiration speed to prevent frothing. You can also adjust the dispense speed and utilize a touch-off to ensure complete liquid ejection [6].

- Pre-Wet the Tip: Aspirate and fully expel the liquid at least three times before the actual transfer. This pre-wets the tip, coating the interior with liquid to reduce surface tension effects and prevent bubble formation [8].

Q4: I am getting variable results when dispensing small volumes of ethanol. What could be wrong?

- Problem: Inconsistent volumes with volatile solvents.

- Solutions:

- Counteract Evaporation: The high vapor pressure of solvents like ethanol causes rapid evaporation in the tip. Implement a larger air gap and use slower, smoother dispensing motions to minimize this effect. If possible, pre-wet the tip to saturate the air cushion with vapor, reducing further evaporation [6] [8].

- Check Temperature: Allow liquids and equipment to equilibrate to the ambient temperature of the lab. Temperature fluctuations exacerbate evaporation and volume delivery errors in air displacement pipettes [8].

- Consider Positive Displacement: For the highest accuracy with volatile solvents, positive displacement systems are preferred as they eliminate the air cushion entirely [6].

Essential Techniques & Optimization Guides

Experimental Protocol: Liquid Class Creation for a New Solvent

This protocol provides a systematic methodology for developing and validating a custom liquid class for a solvent not found in your system's predefined library.

- Define Solvent Properties: Document the solvent's key properties: viscosity (cP), surface tension (mN/m), and vapor pressure (mmHg) at your working temperature.

- Select a Base Liquid Class: Start with a predefined liquid class for a solvent with the most similar properties (e.g., start with a DMSO class for a new organic solvent).

- Optimize Aspiration Parameters:

- Speed: Begin by reducing the default aspiration speed by 50-80% for viscous liquids. For volatile liquids, a moderate reduction can prevent bubbling.

- Delay: Introduce a 1-3 second delay after aspiration to allow the liquid to settle and reach equilibrium [7].

- Immersion Depth: Ensure sufficient depth to prevent air aspiration but avoid excessive depth that causes liquid to cling to the tip exterior.

- Optimize Dispensing Parameters:

- Speed: Reduce dispensing speed significantly for viscous liquids. For volatile liquids, a slower speed minimizes dripping.

- Mode: Choose between free dispense (jetting) for speed or wet dispense (touch-off) for precision and to handle residual droplets [6].

- Delay: Add a post-dispense delay to allow viscous liquids to fully leave the tip.

- Validate and Calibrate:

- Perform a gravimetric analysis: Dispense the target volume multiple times into a microbalance to measure accuracy and precision (CV).

- Adjust parameters iteratively until the measured volume is within your required tolerance.

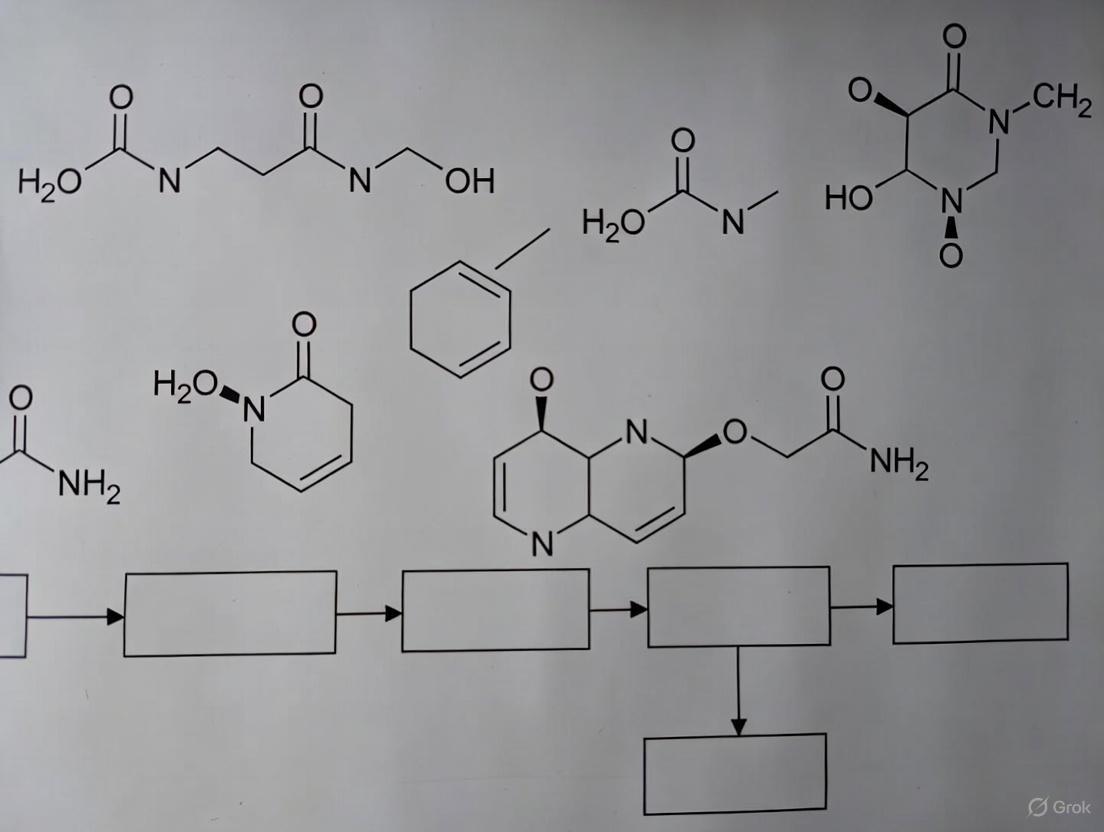

Decision Workflow for Handling Challenging Solvents

The following diagram outlines the logical process for selecting the correct handling method based on the dominant property of your solvent.

Quantitative Solvent Properties and Handling Parameters

The table below summarizes the key properties of common laboratory solvents and recommends initial liquid class adjustments to guide your experimentation.

| Solvent | Viscosity (cP) | Surface Tension (mN/m) | Vapor Pressure | Primary Challenge | Recommended Liquid Class Adjustments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | ~1.0 [6] | ~72 | Low | Baseline | Default parameters. Use for calibration. |

| Glycerol | ~1400 [6] | ~64 | Very Low | High resistance to flow, tip clinging | Greatly reduce aspiration/dispense speed (up to 80%). Use reverse pipetting or positive displacement. Increase delay times [6]. |

| DMSO | ~2.2 [6] | ~43 | Medium | Hydroscopic, droplet formation | Reduce aspiration/dispense speeds. Add an air gap. Use low-retention tips [6] [9]. |

| Ethanol | ~1.2 | ~22 | High | Rapid evaporation, volume loss | Slower, smoother dispensing. Use a larger air gap. Allow temp equilibration [6] [8]. |

| Tween 20 | ~400 [9] | ~30-40 | Low | High adhesion, foam/bubble formation | Slow aspiration to prevent foam. Use wet dispense (touch-off). Pre-wet tips [9]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Positive Displacement Pipetting System | For highly viscous or volatile liquids. The piston contacts the sample, eliminating the compressible air cushion, which nullifies the effects of viscosity and vapor pressure [6] [7]. |

| Low-Retention Pipette Tips | Treated to be hydrophobic, minimizing liquid adhesion to the tip wall. Crucial for maximizing recovery of precious, viscous, or low-surface-tension samples [7] [9]. |

| Wide-Bore (Large-Orifice) Tips | Feature a broader opening to reduce flow resistance, enabling smoother handling of very thick solutions, gels, or cellular samples without clogging [9]. |

| Chemical Compatibility Chart | A critical reference to ensure that solvents will not degrade pump, valve, or tubing materials (e.g., PTFE, PEEK, FFKM) in the automated system, preventing failure and contamination [1]. |

| Gravimetric Scale | The gold standard for validating volume accuracy and precision when creating or troubleshooting a liquid class. It measures the actual mass of liquid dispensed [6]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Why can’t I just use the water liquid class for all my solvents? A: Using an inappropriate liquid class is a primary source of error. Water has a unique balance of viscosity, surface tension, and vapor pressure. A different solvent will not behave the same way. For example, a viscous liquid aspirated with water settings will contain less volume due to higher flow resistance, while a volatile solvent will lose volume to evaporation in the tip [6].

Q: When should I use reverse pipetting versus forward pipetting? A: Use reverse pipetting for viscous liquids, foaming solutions, or when maximum accuracy is critical for small volumes. It accounts for the liquid that adheres to the tip. Use standard forward pipetting for routine aqueous solutions, as it provides excellent accuracy and precision for these liquids and is the default for most predefined liquid classes [8].

Q: How does temperature affect the handling of solvents? A: Temperature is a critical factor. It directly affects a solvent's viscosity and vapor pressure. A cold solvent is more viscous and harder to pipette accurately, while a warm solvent is less viscous but more volatile, increasing the risk of evaporation. Always allow your solvents and equipment to equilibrate to the ambient lab temperature for consistent results [6] [8].

Q: My automated system is still inaccurate after adjusting the liquid class. What else should I investigate? A: First, verify the chemical compatibility of your solvent with the fluid path of the system. An incompatible solvent can degrade seals or tubing, causing micro-leaks and inaccuracies [1]. Second, ensure you are using high-quality, manufacturer-recommended tips. Mismatched or poor-quality tips can fail to form an airtight seal, leading to volume variation [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Chemical Compatibility and Material Failure

Problem: Recurring leaks in pump manifolds and valves. Leaks in an automated liquid handling system often stem from chemical incompatibility, where the solvent degrades the wetted materials. This can lead to catastrophic instrument failure and compromised experimental results [1].

Investigation & Diagnosis:

- Step 1: Identify the Exact Solvent Formulation. Note the precise chemical name, concentration, and any additives. A chemical at 80% concentration may severely degrade a material that is compatible with the same chemical at 20% [1].

- Step 2: Consult a Chemical Compatibility Chart. Use an online database, such as the Cole-Parmer Chemical Compatibility Database, to check the resistance rating of your component's material (e.g., PTFE, PEEK, SS 316) against your specific solvent. Look for ratings worse than "Good" [1].

- Step 3: Visually Inspect Components. Check for signs of degradation, including discoloration, swelling, pitting, corrosion, or cracking [1].

Resolution:

- Immediate Action: Replace the damaged component and contain any leakage to prevent instrument damage.

- Corrective Action: Select a new component made from a material with an "Excellent" or "Good" compatibility rating for your solvent. For example, ceramic components may be suitable for detergents at elevated temperatures, while PEEK is often a better alternative for strong bases than polycarbonate [1].

Prevention:

- Confirm the exact material of all wetted components (e.g., the difference between SS 304 and SS 316 matters for salt resistance) [1].

- Consider all operating conditions, including temperature, as compatibility can diminish above standard room temperature (22°C) [1].

Poor Precision with Volatile Solvents

Problem: Inaccurate low-volume dispensing of organic solvents. Aqueous liquid handling methods often fail with volatile solvents, leading to inaccurate volumes due to evaporation, "filming" on pipette tips, and droplet formation [3].

Investigation & Diagnosis:

- Step 1: Check Environmental Controls. High airflow (needed for safety) can exacerbate evaporation of low volumes (<20 µL). Use a static meter to check for charge buildup (>2 kV), which can disrupt solvent transfers [3].

- Step 2: Observe Dispensing Behavior. After a dispense, watch for solvent "filming"—where residual solvent wicks down the tip orifice and forms micro-droplets that can drip or pop off unpredictably [3].

- Step 3: Review Tip Selection and Type. Using filtered tips reduces the cavity space for solvent volatilization, which can disrupt equilibrium and lead to dispensing errors. Non-filtered tips provide a larger cavity and more stable performance for volatile solvents on compatible systems [3].

Resolution:

- Optimize Pipetting Parameters: In the liquid handler's software (e.g., Method Manager), adjust parameters. Implement a post-dispense pause to allow residual film to coalesce and dispense fully. For polar solvents, use a fast aspirate speed and a slow dispense speed to minimize filming [3].

- Manage Static: Install ionization bars to neutralize static charge buildup on the instrument deck [3].

- Select Appropriate Tips: For ST-class systems, switch to non-filtered tips to increase the vapor cavity and improve equilibrium, if protocol allows [3].

Prevention:

- Always validate solvent methods in the same temperature and airflow environment used for production [3].

- Check chemical compatibility charts for long-term interactions between your solvents and pipette tip material (e.g., polypropylene) [3].

Contamination and Carryover

Problem: Cross-contamination between samples. Carryover can ruin experimental integrity, leading to false positives and unreliable data [10].

Investigation & Diagnosis:

- Step 1: Identify Contamination Source. Determine if contamination is from a reusable tip, a fixed fluid path, or splashing during high-speed movement.

- Step 2: Check Wash Protocols. For systems with fixed tips, ensure the wash solvent is effective and volumes are sufficient to clean the interior surfaces [11].

Resolution:

- Use Disposable Tips: Implement filtered or non-filtered disposable tips to eliminate carryover from reusable components [12] [13].

- Employ Non-Contact Dispensing: Technologies like acoustic droplet ejection or air displacement dispensers eliminate tip-to-sample contact, virtually eradicating carryover [10].

- Optimize Wash Protocol: For fixed-tip systems, use a wash solvent that is compatible with both the component material and the residues being flushed [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Beyond the chart, what are the most common mistakes in solvent compatibility assessment? The most common mistakes are:

- Ignoring Concentration: A chemical at 20% may be compatible, while at 80% it may cause failure [1].

- Overlooking Temperature: A solvent compatible at 22°C may rapidly degrade components at 37°C [1].

- Assuming Material Grades are Equal: SS 316 contains molybdenum for superior salt resistance compared to SS 304, a critical detail for biochemical buffers [1].

- Neglecting Chemical Mixtures: Compatibility charts typically list pure chemicals, but mixtures can have unforeseen effects [1].

Q2: My liquid handler is suddenly inaccurate with methanol. What should I check first? First, check for static charge buildup on the instrument deck. Static can unpredictably disrupt solvent transfers, especially at low volumes. Use a static meter; a reading above 2 kilovolts is problematic. Second, observe the dispense for "filming"—where residual solvent forms droplets on the tip's exterior. This indicates a need to adjust dispense speeds and add a post-dispense pause in your method [3].

Q3: How can I safely handle flammable solvents near instrumentation that uses lasers? This is a critical safety hazard, as laser beams can ignite solvent vapors.

- Engineering Controls: Ensure powerful lasers (Class 3B or 4) are fully enclosed with safety interlocks. Use explosion-proof local exhaust ventilation (LEV) over solvent dispensing points to keep vapor concentrations below the Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) [14].

- Administrative Controls: Appoint a Laser Safety Officer, enforce strict SOPs, and conduct a combined-risk assessment with your Chemical Hygiene Officer [14].

Q4: What is the single most impactful upgrade to improve reproducibility in liquid handling? Implementing automated liquid handling (ALH) is the most impactful upgrade. ALH systems eliminate operator variability, provide precise control over experimental variables, and ensure the same protocol is executed identically every time. This is crucial for complex methods like Design of Experiments (DoE) and is a cornerstone of reproducible science [10] [12].

Chemical Compatibility Impact on Formulation Development

Table: Consequences of High-Concentration Formulation Challenges (Survey of 100 Experts)

| Challenge | Percentage of Experts Reporting | Most Severe Outcome Reported |

|---|---|---|

| Solubility Issues | 75% | Clinical trial or product launch delays [15]. |

| Viscosity-related Challenges | 72% | Clinical trial or product launch delays [15]. |

| Aggregation Issues | 68% | Clinical trial or product launch delays [15]. |

| Overall Impact: Delays in Trials/Launches | 69% | Weighted Average Delay: 11.3 months [15] |

| Overall Impact: Project Cancellation | 4.3% | Trial or product launch canceled entirely [15]. |

Performance Specifications of Automated Liquid Handling (ALH) Technologies

Table: Comparison of Common ALH Dispensing Technologies [12]

| Technology | Precision (CV) | Liquid Class Compatibility | Key Contamination Risk Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro-Diaphragm Pump (e.g., Mantis) | < 2% at 100 nL | Up to 25 cP | Non-contact dispensing with isolated fluid path [12]. |

| Micro-Diaphragm Pump (e.g., Tempest) | < 3% at 200 nL | Up to 20 cP | Non-contact dispensing with isolated fluid path [12]. |

| Positive Displacement (e.g., F.A.S.T.) | < 5% at 100 nL | Liquid class agnostic | Disposable tips [12]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Optimizing Robotic Pipetting Scheduling as a Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem (CVRP)

Application: This protocol is designed to significantly reduce the execution time of combinatorial liquid handling tasks on systems with 8 individually controllable tips, without any hardware modifications. It is ideal for high-throughput screening, drug combination studies, and materials discovery [11].

Methodology:

- Define the Task Matrix: Encode the liquid transfer task as a matrix where non-zero entries ( t_{a,b} ) represent the volume to be transferred from source well ( a ) to destination well ( b ) [11].

- Formulate as CVRP: Model the problem where the 8-channel pipette is a "vehicle" with a capacity of 8 deliveries per cycle. Each (source, destination) pair is a "location" to be visited [11].

- Define Pairwise Distance: Create a distance matrix ( D ) where the "distance" between two wells is 0 if they are in the same column and adjacent rows (enabling parallel aspiration/dispensing), and 1 otherwise. This focuses the optimization on minimizing the number of slow tip-raising and lowering cycles [11].

- Apply Heuristic Solver: Use a standard CVRP heuristic solver to find the sequence of operations that minimizes the total estimated execution time. The primary time costs per cycle are tip lowering (( t1 )), aspirating/dispensing (( t2 )), tip raising (( t3 )), and arm movement (( t4 )) [11].

Expected Outcome: This method demonstrated a 37% reduction in execution time for randomly generated tasks and saved 61 minutes in a real-world high-throughput materials discovery campaign compared to standard sorting methods [11].

Protocol: Method Development for Reliable Solvent Transfers

Application: Establish a robust method for handling volatile and polar solvents (e.g., methanol, hexane, MTBE) on automated liquid handlers, minimizing errors from evaporation and filming [3].

Methodology:

- Environmental Setup:

- Tip and System Selection:

- For maximum stability with volatile solvents, use an ST-class liquid handler with non-filtered tips. The larger internal cavity better manages vapor pressure equilibrium [3].

- Confirm the chemical compatibility of the tip material (e.g., polypropylene) with the solvent for the intended protocol duration [1] [3].

- Pipetting Parameter Optimization (in Software):

- For Polar Solvents: Use a fast aspirate speed and a slow dispense speed to reduce filming [3].

- Post-Dispense Pause: Introduce a 1-5 second pause after dispense to allow residual solvent film on the tip to coalesce and fall [3].

- Pause Before Moving: For critical low-volume transfers, program a brief pause before the pipette head moves to prevent droplets from falling in the wrong well during travel [3].

Workflow Diagrams

Solvent Compatibility Assessment Pathway

Troubleshooting Volatile Solvent Dispensing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Materials for Robust Solvent Handling

| Item | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| PEEK (Polyetheretherketone) | A high-performance polymer for manifolds, valves, and tubing. | Excellent chemical resistance against a wide range of solvents, salts, and bases. Superior to polycarbonate for strong bases [1]. |

| PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene) | A fluoropolymer used for seals and fluid paths. | Nearly inert, with excellent resistance to aggressive solvents and acids [1]. |

| SS 316 (Stainless Steel 316) | Metal alloy for components requiring strength. | Contains molybdenum for enhanced resistance to corrosion by salts, common in biochemical buffers. Prefer over SS 304 [1]. |

| Ceramic Components | Used for parts in contact with detergents and reagents at elevated temperatures. | Maintains excellent compatibility where SS 316 begins to degrade above 22°C [1]. |

| Polypropylene Pipette Tips | Disposable tips for sample handling. | Generally compatible with most solvents for short-term exposure, but check charts for long-term use with solvents like hexane or MTBE [3]. |

| Ionization Bars | Device to neutralize static charge on the instrument deck. | Critical for preventing unpredictable solvent behavior, especially for low-volume (<20 µL) transfers of polar solvents [3]. |

| Chemical Compatibility Database | Online reference tool (e.g., Cole-Parmer). | Essential for pre-screening material compatibility with specific solvents and concentrations before designing experiments [1]. |

Material Profiles and Key Properties

This section details the core materials—PEEK, PTFE, and Stainless Steel 316—commonly used in fluidic paths for automated liquid handling, highlighting their properties relevant to solvent compatibility.

Polyether Ether Ketone (PEEK)

PEEK is a high-performance semi-crystalline thermoplastic from the polyaryletherketone (PAEK) family, known for its excellent mechanical strength, good chemical resistance, and biocompatibility [16]. Its molecular structure consists of aromatic rings linked by ether and ketone groups, providing robustness [16].

- Key Properties: Tensile strength of 90-100 MPa, excellent creep resistance, and a melting point of approximately 343°C [17] [16]. Its elastic modulus is comparable to cortical bone, making it suitable for biomedical applications [16].

- Chemical Considerations: Resists a wide range of common solvents but is susceptible to strong oxidizing acids like concentrated sulfuric and nitric acids. Swelling can occur with solvents like DMSO, THF, and methylene chloride [18] [17] [19].

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)

PTFE, a fully fluorinated synthetic fluoropolymer, is renowned for its exceptional chemical inertness and one of the lowest coefficients of friction among solids [18] [17] [19].

- Key Properties: Tensile strength of 25-35 MPa and a continuous service temperature up to 260°C [17]. It is highly flexible and usable at cryogenic temperatures down to -200°C [17].

- Chemical Considerations: It is considered the most chemically inert polymer, resistant to virtually all acids, bases, solvents, and corrosive media, except for a few extremely reactive substances like fluorine gas at high temperatures or molten alkali metals [17] [19]. It is physiologically inert and FDA-approved for food and pharmaceutical uses [18] [17].

Stainless Steel 316 (SS 316)

SS 316 is an austenitic stainless steel valued for its corrosion resistance and mechanical strength in high-pressure fluidic systems [18]. Its resistance is derived from a chromium oxide passive layer that forms on the surface.

- Key Properties: Inherently corrosion-resistant due to its composition of chromium, nickel, and molybdenum [18]. The addition of ~2% molybdenum specifically enhances its resistance to chlorides and salts compared to other grades like SS 304 [1].

- Chemical Considerations: While resistant to many chemicals, the passive layer can be vulnerable to chlorides, leading to pitting corrosion, and to strong acids [20] [21]. It is also susceptible to Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion (MIC) in stagnant water environments [20].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Key Material Properties

| Property | PEEK | PTFE | SS 316 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | 90 - 100 [17] | 25 - 35 [17] | ~500 (Yield) [20] |

| Continuous Service Temp. | Up to 250°C [19] | Up to 260°C [17] | Varies with environment |

| Coefficient of Friction | ~0.35 [17] | ~0.05 (Virgin) [17] | N/A |

| Key Chemical Weakness | Concentrated H₂SO₄, Halogenated Acids [17] | Molten Alkali Metals [17] | Chlorides, Stagnant Water [20] |

Chemical Compatibility and Selection Guide

Selecting the correct material requires careful evaluation of the chemical environment, including concentration, temperature, and pressure.

The following table provides a high-level guide to the chemical resistance of each material. Always consult detailed compatibility charts and perform tests before final selection [1].

Table 2: Chemical Compatibility Guide for Common Solvents

| Chemical | PEEK | PTFE | SS 316 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetic Acid, 50% | Excellent [21] | Excellent [21] | Excellent [21] |

| Acetone | Excellent [21] | Excellent [21] | Excellent [21] |

| Hydrochloric Acid, 35% | Good | Excellent [21] | Not Recommended [21] |

| Sulfuric Acid, 98% | Severe Attack [17] | Excellent [21] | Not Recommended [21] |

| Methylene Chloride | Swelling [18] | Excellent [21] | Excellent [21] |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Swelling/Attack [18] [21] | Excellent [21] | Excellent [21] |

| Sodium Hydroxide, 20% | Excellent | Excellent [21] | Good to Excellent [1] |

Material Selection Workflow

Follow this logical decision process to select the appropriate fluid path material for your application.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

This section addresses specific failures and provides diagnostic steps for researchers.

Leaks or Pressure Loss in SS 316 Systems

- Problem: Sudden pressure loss or visible leaks in stainless steel tubing or fittings.

- Diagnosis:

- Visual Inspection: Examine the inner wall for localized pitting corrosion, often surrounded by a "clean" area and an outer crown of reddish oxidation products [20].

- Environmental Check: Determine if the system was exposed to stagnant water, especially in marine or port environments, or if chlorides were present [20].

- Laboratory Analysis: For critical failures, SEM/EDS analysis of pits can reveal characteristic morphologies, and bacterial culture (for Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria) of internal stagnant water can confirm MIC [20].

- Solution: Flush and dry systems thoroughly after use. For installations prone to stagnation, specify passivated SS 316 or consider alternative materials like PEEK for specific sections. Replace damaged tubing.

Deformation or Failure of Polymer Components

- Problem: PEEK or PTFE seals, valves, or tubing show swelling, cracking, or extrusion.

- Diagnosis:

- Material Verification: Confirm the polymer type used (e.g., Virgin PTFE vs. PEEK).

- Chemical Exposure Review: Audit all solvents and reagents that contacted the component. Check for known incompatible chemicals (e.g., concentrated sulfuric acid with PEEK, or strong caustics with certain filled-PTFE) [17] [22] [21].

- Operating Condition Check: For PTFE, cold flow (creep) can occur under continuous high load. For PEEK, verify that operating temperatures were within the specified range [17] [22].

- Solution: Immediately replace with a compatible material. For high-pressure applications, use glass- or carbon-filled PTFE or PEEK for superior extrusion resistance [17] [22].

Poor Sealing and High Stem Torque in Valves

- Problem: Difficulty operating ball valves or increased torque, leading to poor sealing.

- Diagnosis:

- Friction Check: This is common with PTFE seats if the coefficient of friction increases due to incompatibility or lack of lubrication [22].

- Wear Inspection: Look for abrasive wear on polymer seats, especially in applications with particulates. PEEK generally offers better abrasion resistance than virgin PTFE [17] [22].

- Chemical Compatibility: Verify that the valve seat material is compatible with the fluid. For example, PEEK is not suitable for corrosive environments like those with sulfuric acid [22].

- Solution: For low-friction needs, select virgin PTFE seats. For abrasive or high-pressure/high-temperature environments, choose PEEK or carbon-filled PTFE seats [17] [22].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can I use PEEK tubing with acetonitrile in my UHPLC system? A: For most UHPLC applications with acetonitrile, PEEK tubing is an excellent choice due to its high-pressure tolerance and chemical resistance. However, be cautious with very high concentrations of acetonitrile, as it can cause some swelling in PEEK [18]. For critical applications, PEEK-lined stainless steel or PEEKsil tubing provide an inert fluid path while maintaining high-pressure capability [18].

Q2: My application involves switching between many different solvents. What is the safest material choice? A: PTFE offers the broadest chemical compatibility and is often the safest choice for systems with frequent solvent changes, as it is inert to virtually all common solvents [17] [19]. The main trade-offs are its lower mechanical strength and higher creep tendency compared to PEEK.

Q3: Why did my SS 316 system fail, even though the chemical compatibility chart rated it as "Excellent"? A: Chemical compatibility charts are guides, not guarantees. Failure can occur due to:

- Extended Stagnation: Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion (MIC) can rapidly cause pitting in stagnant water [20].

- Temperature Effects: Compatibility can diminish at elevated temperatures, even if rated "Excellent" at room temperature [1].

- Minor Constituents: Impurities or specific chemical formulations not covered in the chart can cause unexpected attacks [1]. Always test under your specific operating conditions.

Q4: When should I choose PEEK over PTFE for a seal? A: Choose PEEK when your application requires:

- High Mechanical Strength and Creep Resistance: For structural components or under continuous high load [17].

- Superior Wear Resistance: In abrasive environments or for dynamic sealing applications [17] [22].

- Higher Operating Temperatures under Load: PEEK maintains dimensional stability better than PTFE at high temperatures [17] [19].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Static Immersion Test for Chemical Compatibility

This method provides a preliminary assessment of a material's resistance to a specific chemical [1].

- Sample Preparation: Cut standardized coupons (e.g., 25mm x 25mm x 3mm) of the candidate materials (PEEK, PTFE, SS 316). Polish surfaces to a consistent finish, clean, and dry thoroughly. Weigh each sample to a precision of 0.1 mg and record initial dimensions and weight.

- Immersion Test: Immerse each sample in a sealed glass container with the test solvent, ensuring complete coverage. Use triplicates for each material-solvent combination. Include a control container with solvent only.

- Exposure Conditions: Place containers in an environmental chamber if temperature control is needed (e.g., 22°C, 37°C). A typical exposure period is 48-96 hours [21].

- Post-Test Analysis:

- Visual Inspection: Examine for discoloration, cracking, crazing, or swelling.

- Gravimetric Analysis: Rinse, dry, and re-weigh samples. Calculate weight change as a percentage.

- Dimensional Measurement: Measure for any swelling or deformation.

- Mechanical Test: If possible, perform a comparative tensile or hardness test on exposed vs. unexposed samples.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Fluid Path Experimentation

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| PEEK Tubing (1/16" OD) | The standard for high-pressure HPLC/UHPLC fluidic paths. Offers a good balance of pressure rating, flexibility, and chemical resistance for many organic and aqueous solvents [18]. |

| PTFE Tubing | Ideal for peristaltic pumps, gas lines, and low-pressure applications involving highly aggressive chemicals where inertness is paramount [18]. |

| SS 316 Tubing (1/16" OD) | Used for high-pressure applications where solvents are compatible and maximum mechanical rigidity is required. Prone to corrosion with halides and strong acids [18] [20]. |

| PEEK-Lined SS Tubing | Combines the chemical inertness of a PEEK fluid path with the mechanical strength and pressure rating of a stainless steel jacket. Ideal for bioinert UHPLC applications [18]. |

| Virgin PTFE Seals | Provide the best sealing with the lowest friction in ball valves and fittings for non-abrasive, chemically aggressive fluids [22]. |

| Carbon-Filled PTFE Seals | Offer improved wear resistance, reduced cold flow, and higher load-bearing capacity compared to virgin PTFE, suitable for more demanding applications [17] [22]. |

| PEEK Seals | Used in high-temperature, high-pressure, and abrasive environments. Superior mechanical and creep resistance compared to PTFE [17] [22]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is a liquid class in automated liquid handling? A liquid class is a set of software-defined parameters that translates a liquid's physical properties into specific mechanical commands for the pipetting system [23]. It ensures accurate and reproducible liquid transfer by defining how the instrument should handle liquids with different characteristics, such as viscosity, surface tension, and vapor pressure [23].

2. Why is using the correct liquid class critical for my experiments? Using the correct liquid class is fundamental for data integrity. Miscalibrated liquid handling can cause significant deviations in assay results [23]. For example, in biochemical assays, minor volume delivery errors can notably affect measurements of inhibitor potency (IC50) [23]. Proper liquid classes ensure precision, reduce variation by 60-70% compared to manual methods, and support reproducibility [23].

3. My liquid handler is dripping. Could the liquid class be the problem? Yes. A dripping tip or a drop hanging from the tip is often related to an incorrect liquid class for the solvent's properties [24]. This is common when handling liquids with different vapor pressure or viscosity than water [23] [24]. Solutions include sufficiently pre-wetting tips, adding an air gap after aspiration, or adjusting aspirate and dispense speeds [24].

4. How do I handle volatile solvents like acetone or ethanol? Volatile solvents require specific liquid class adjustments to counteract their high vapor pressure, which can cause evaporation and volume loss [23]. Key adjustments include using slower aspiration and dispensing speeds to prevent turbulence, implementing extended delay times, and employing larger air gaps [23]. Using positive displacement tips, which eliminate the compressible air cushion, is also highly recommended for these liquids [23].

5. What is the difference between wet and free (dry) dispensing, and when should I use each? The choice depends on your priority between precision and speed [23].

- Wet Dispensing: The pipette tip contacts the liquid or vessel surface during dispensing. This improves accuracy and repeatability by minimizing residual solution in the tip and is ideal for thick liquids, small volumes (sub-microliter), or when reduced dead volume is critical [23] [24]. It can, however, be slower and carries a risk of cross-contamination if a tip touches multiple vessels [23].

- Free (or Jet) Dispensing: Liquid is dispensed without the tip contacting the vessel. This method is faster and reduces cross-contamination risk, making it ideal for high-throughput tasks like filling a 96-well plate [23]. It is best suited for aqueous solutions but may require more optimization for viscous or volatile liquids [23].

Troubleshooting Guide

This section addresses specific liquid handling errors, their common sources, and potential solutions.

| Observed Error | Possible Source & Relation to Liquid Class | Possible Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Dripping Tip [24] | Liquid's vapor pressure differs from water; class lacks adjustments for volatility [23] [24]. | Sufficiently pre-wet tips; add an air gap after aspiration; use positive displacement [23] [24]. |

| Droplets/Tailing Liquid [24] | High viscosity/adhesion not accounted for; standard "aqueous" class used [23]. | Adjust (slow) aspirate/dispense speed; add air gaps/"blow outs" [24]. |

| Inaccurate Volume (Bubbles) [25] | Rapid plunger release traps air; class speed too fast for liquid's cohesion [23] [25]. | Use slow, steady plunger action; ensure tip is fully submerged; optimize speed [25]. |

| Serial Dilution Inaccuracy [24] | Insufficient mixing in class leads to concentration gradients [24]. | Increase mixing steps (number, efficiency) in the liquid class protocol [24]. |

| Variable First/Last Dispense [24] | "Sequential dispense" artifact; residual liquid retained differently. | Dispense first/last quantity into a waste reservoir [24]. |

Liquid Properties and Handling Parameters

This table summarizes key liquid properties and how they influence critical parameters in a liquid class.

| Liquid Property | Impact on Pipetting | Liquid Class Adjustments |

|---|---|---|

| Viscosity (e.g., Glycerol) [23] | Resists flow; can form fluid strings, sticks to tips [23]. | Slower aspiration/dispense speeds (up to 80% slower); increased tip immersion depth; extended delay times; use positive displacement [23]. |

| Surface Tension (e.g., DMSO) [23] | Affects liquid interaction with tip; can cause droplet hanging [23]. | Adjust aspirate/dispense speeds; consider wet dispensing to control adhesion/cohesion forces [23] [24]. |

| Vapor Pressure (e.g., Acetone, Ethanol) [23] | Causes evaporation, volume loss, and dripping [23] [24]. | Slower speeds; extended delay times; larger air gaps; use of positive displacement tips [23]. |

| Density [23] | Affects the mass of the liquid for a given volume. | Typically accounted for in gravimetric calibration but is a fundamental property defined in the class [23]. |

Experimental Protocol: Verifying Liquid Handler Performance for Complex Reagents

This protocol is adapted from methodologies cited in scientific literature to accurately assess liquid-handler performance when dispensing complex or non-aqueous reagents [26].

1. Objective To verify the accuracy and precision of an automated liquid handler when dispensing non-aqueous and complex reagent solutions (e.g., DMSO, glycerol, ethanol).

2. Materials and Reagents

- Automated liquid handler (air displacement or positive displacement)

- Analytical balance (capable of µg resolution)

- High-quality, low-evaporation microplates or tubes

- Test reagents:

- Aqueous control: Pure water

- Non-aqueous solvents: 75-90% DMSO (v/v), 50% Ethanol (v/v)

- Viscous solution: 20% Glycerol (v/v)

- Dual-dye ratiometric photometry kit (optional, for orthogonal validation) [26]

3. Methodology Step 1: Gravimetric Calibration Setup

- Tare the balance with a clean, dry receiving vessel.

- Program the liquid handler to dispense the target volume (e.g., 1 µL, 10 µL) of each test reagent into the vessel.

- For each liquid, perform a minimum of n=8 replicates to establish a mean and coefficient of variation (CV) [25].

Step 2: Dispensing and Measurement

- Dispense the liquid into the tared vessel. Record the weight immediately after each dispense to minimize evaporation error, especially for volatile solvents [25].

- Convert the mass measured to a volume using the known density of the liquid at room temperature.

- Calculate the accuracy (% deviation from target volume) and precision (% CV) for each liquid type.

Step 3: Data Analysis and Liquid Class Refinement

- Compare the accuracy and precision of the non-aqueous reagents against the aqueous control and your predefined tolerance windows (e.g., ±5% accuracy, <10% CV).

- If performance is outside tolerance, refine the liquid class parameters. For example:

- For DMSO/Glycerol: Reduce aspiration and dispense speeds; add delays.

- For Ethanol: Introduce a larger air gap; use a slower, more controlled dispense speed.

- Repeat the gravimetric verification with the updated liquid class until performance is acceptable.

Step 4: Orthogonal Validation (Optional)

- For critical applications, validate the final performance using dual-dye ratiometric photometry, a method cited for validating aliquots of multiple solutions where gravimetry may be influenced by evaporation or density [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Context of Solvent Handling |

|---|---|

| Positive Displacement Tips | Tips with a built-in piston that contacts the liquid. Essential for volatile solvents (DMSO, ethanol) and viscous liquids (glycerol) as they eliminate the compressible air cushion, preventing evaporation and ensuring accuracy [23]. |

| Air Displacement Tips | Standard tips that use an air cushion to move liquid. Suitable for aqueous solutions but require significant parameter adjustment for other solvent types [23]. |

| Dual-Dye Ratiometric Photometry Kit | Used for orthogonal validation of dispensed volumes, especially for small volumes or complex solvents where gravimetric methods can be affected by evaporation [26]. |

| Non-Polar Solvents (e.g., Hexane) | Used in extraction and characterization studies to detect non-polar contaminants (e.g., lubricants, machine oils) that are insoluble in polar solvents, ensuring a complete safety assessment [27]. |

| Protic Solvents (e.g., Water, IPA) | Polar, reactive solvents (O-H or N-H bonds) commonly used for extraction and biocompatibility testing. Can alter chemical structures of some reactive extractables, requiring careful data interpretation [27]. |

| Aprotic Solvents (e.g., DCM, Acetonitrile) | Unreactive polar solvents that lack O-H/N-H bonds. Ideal for extracting reactive chemicals (e.g., residual isocyanates from polyurethanes) without causing chemical alteration, providing a true extractables profile [27]. |

Logical Workflow for Liquid Handling Troubleshooting

The following diagram outlines a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving liquid handling errors, connecting observed problems to their root causes and solutions.

Building a Robust Method: A Step-by-Step Guide to Solvent and Material Selection

Why is Solvent Profiling Critical for Automated Liquid Handling?

In automated liquid handling research, a solvent's physical and chemical properties directly influence its behavior during aspiration, dispensing, and transfer. Using a solvent without understanding its profile can lead to inaccurate volumes, damaged equipment, and failed experiments. Profiling your solvent is the first and most crucial step in ensuring compatibility, assay integrity, and operational safety [28] [29].

The Essential Chemical Property Checklist

When preparing a new solvent for use, systematically check the following properties. This list consolidates key factors that affect how a solvent interacts with automated liquid handlers, fluid paths, and labware [28] [30] [24].

| Property Category | Specific Property to Check | Why It Matters in Automation |

|---|---|---|

| General Properties | Chemical Name & Formula | Prevents accidental misuse of incompatible chemicals [29]. |

| Concentration / Purity | Significantly alters chemical behavior (e.g., Glacial Acetic Acid vs. dilute) [31]. | |

| Physical Properties | Viscosity | Impacts aspirate/dispense speeds; highly viscous liquids require slower rates [24]. |

| Vapor Pressure | High vapor pressure can cause "dripping tips" and volume inaccuracies, especially in acoustic handlers [24]. | |

| Density & Specific Gravity | Affects liquid sensing and volume calculations in some systems. | |

| Surface Tension | Influences droplet formation, aspiration, and dispensing, particularly in low-volume transfers [28]. | |

| Chemical Compatibility | Material Compatibility (e.g., PP, PTFE, Stainless Steel) | Check against seals, tubing, tips, and reservoir materials to prevent swelling, corrosion, or failure [32] [33]. |

| Functional Group | Helps predict chemical behavior and potential incompatibilities (e.g., aldehydes, ketones) [30] [29]. | |

| Safety & Handling | Flash Point / Flammability | Critical for lab safety and determining storage requirements [30]. |

| Health & Environmental Impact | Informs required personal protective equipment (PPE) and waste disposal [30]. |

Experimental Protocol: Solvent & Material Compatibility Testing

Before running a full experiment, validate that your solvent is compatible with the liquid handler's components.

1. Objective: To determine if a solvent causes unacceptable degradation, swelling, or corrosion to materials it contacts in the automated system.

2. Materials Needed:

- Solvent of interest

- Small samples of materials used in your liquid handler (e.g., O-rings made of various elastomers, tubing, tip plastic)

- Inert containers (e.g., glass vials)

3. Methodology:

- Immersion Test: Immerse the material samples in the solvent for a defined period, typically 24-48 hours, at room temperature [33].

- Condition Simulation: For a more accurate test, simulate conditions like elevated temperature or pressure if they are part of your process.

- Inspection and Measurement:

- Visual Inspection: Check for discoloration, cracking, swelling, or dissolution.

- Weight Measurement: Weigh the samples before and after immersion. A significant change in mass indicates absorption or degradation.

- Functional Check: After drying, check if the material still performs its function (e.g., does an O-ring still seal?).

4. Interpretation: Any significant change in the material's properties indicates incompatibility. You should select an alternative material before proceeding [32] [29].

Troubleshooting Common Solvent-Related Liquid Handling Errors

Unexpected results are often traced to solvent-property mismatches. The table below outlines common issues and their solutions.

| Observed Error | Possible Root Cause | Proven Solutions and Adjustments |

|---|---|---|

| Dripping tips or hanging drops | High vapor pressure or low surface tension [24]. | - Sufficiently pre-wet tips.- Add a trailing air gap after aspiration [24]. |

| Droplets or trailing liquid during movement | High viscosity or other adhesive properties [24]. | - Adjust (typically slow down) aspirate/dispense speeds.- Add extra "blow-out" cycles to empty tips completely [24]. |

| Inaccurate volumes with acoustic liquid handlers | Incorrect calibration for the solvent's physical properties [24]. | - Ensure source plates are centrifuged to remove bubbles [34] [24].- Let plates reach thermal equilibrium with the instrument.- Use solvent-specific calibration curves [24]. |

| Serial dilution inaccuracies | Inefficient mixing of viscous solvents, leading to non-homogeneous solutions [28]. | - Increase the number of mix cycles.- Validate mixing efficiency for your specific solvent-well combination. |

| Component failure (e.g., swollen O-rings, cracked tubing) | Chemical incompatibility between the solvent and the wetted materials [32] [33]. | - Consult chemical compatibility charts for seals and tubing [32] [31] [33].- Perform a compatibility test before full-scale use. |

Leverage these established tools and databases to streamline your solvent profiling and selection process.

| Tool / Resource | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| ACS GCI Solvent Selection Tool [30] | Interactive solvent selection based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of physical properties. | - Database of 272 solvents.- Filters based on functional groups and EHS (Environmental, Health, Safety) criteria.- ICH solvent classification. |

| Cole-Parmer Chemical Compatibility Database [32] | Checks chemical resistance of various plastics and elastomers. | - Search by chemical and material.- Provides ratings from "Excellent" to "Poor." |

| Agilent Syringe Filter Compatibility Chart [33] | Aids in selecting compatible filters for sterilization or clarification. | - Compares multiple membrane types (Nylon, PTFE, PES, etc.).- Uses a clear "Compatible/Limited/Not Compatible" rating system. |

Workflow for Solvent Assessment in Automated Systems

The following diagram illustrates the logical process for introducing a new solvent into your automated workflow, from initial profiling to final validation.

By meticulously profiling your solvents using this structured approach, you lay a foundation for robust, reliable, and reproducible automated liquid handling processes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is a chemical compatibility chart, and why is it critical for automated liquid handling?

A chemical compatibility chart is a reference tool that provides ratings on how well a specific material (like a plastic or metal) can resist damage or corrosion when exposed to a particular chemical. It is critical for automated liquid handling (ALH) systems because incompatible chemical-component pairings can lead to catastrophic performance failure, including premature component degradation, tainted test results, and costly instrument downtime [1].

FAQ 2: Where can I find a reliable chemical compatibility database?

Several reputable online databases provide comprehensive chemical compatibility information. The Cole-Parmer Chemical Compatibility Database is a widely used resource that allows you to search and compare chemicals against various materials [32]. Additionally, many laboratory fluid providers and component manufacturers offer compatibility guides specific to their products and the chemicals used in life science applications [1] [29].

FAQ 3: A compatibility chart gave my material-chemical pair a "Good" rating. Is this acceptable for long-term use?

A "Good" rating indicates the material has minor effects, such as slight corrosion or discoloration, after exposure [29]. For long-term use in a precision ALH system, this may not be acceptable. These minor effects can accumulate, potentially leading to diminished performance over time, such as inaccuracies in liquid dispensing. Where possible, selecting a material with an "Excellent" rating—indicating no detectable chemical effect—is recommended for ensuring reliability and longevity [1].

FAQ 4: How do operating conditions like temperature and concentration affect compatibility?

Chemical compatibility is highly dependent on operating conditions [1]. A material that is fully compatible with a chemical at room temperature and low concentration may suffer severe degradation at elevated temperatures or higher concentrations. For example, while stainless steel 316 is rated excellent with many detergents at 22°C, its compatibility can diminish at higher temperatures common in cell culture workflows (37°C) [1]. Always consult compatibility data that matches your specific process conditions.

FAQ 5: What are the most common incompatible chemical groups I should segregate in the lab?

The most hazardous incompatible groups that require segregation are [29] [35]:

- Acids and Bases: Mixing can cause violent neutralization reactions, releasing significant heat.

- Oxidizers and Flammable Materials: Combining can lead to fire or explosion.

- Oxidizers and Organic Compounds: This combination can also result in fire or explosion.

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Cloudy or discolored liquid path components | Chemical attack on the material, such as plastic swelling or cracking [1]. | Check the chemical compatibility chart for your specific chemical and the component material. Replace the component with one made from a more compatible material (e.g., switch from polycarbonate to PEEK) [1]. |

| Crystallization or salt buildup on components | Use of high-salt concentration buffers; some materials have lower resistance to salts [1]. | Confirm the component material is rated "Excellent" for use with salts. For example, ensure you are using SS 316, which contains molybdenum for superior salt resistance, and not the less resistant SS 304 [1]. |

| Unexpected precipitation in solution | Incompatibility between chemicals in the workflow, not just with the hardware [29]. | Review the chemical-chemical compatibility of all reagents and solvents in your protocol. Segregate and sequence the delivery of incompatible solutions, ensuring proper washing steps in between [29]. |

| Poor analytical results or high data variability | Leaching or extraction of chemicals from degraded components into the sample, contaminating it [1]. | Investigate all wetted components (manifolds, seals, tubing) for signs of degradation. Systematically replace components with alternatives made from more inert materials like PTFE or FFKM [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Systematic Method for Component Selection

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for selecting chemically compatible components for your automated liquid handling application, helping to prevent unforeseen failures.

Objective: To systematically identify the most suitable wetted materials for an ALH system component based on the specific chemicals, concentrations, and operating conditions used in the assay.

Materials and Reagents:

- List of all chemicals, reagents, and buffers (including concentrations)

- List of potential ALH component materials (e.g., PTFE, PPS, PEEK, SS 316, FFKM, glass)

- Access to a chemical compatibility database (e.g., Cole-Parmer [32])

Procedure:

- Define the Chemical Environment: Create a comprehensive list of every chemical the component will contact. Note the exact chemical name, concentration, and mixture state (e.g., 70% isopropanol, 1M sodium hydroxide) [1].

- Define the Physical Environment: Record the operating parameters, including the temperature range the component will experience during the protocol and the planned duration of chemical contact [1].

- Consult Compatibility Charts: Using your defined parameters, query a chemical compatibility database for each chemical and potential material. Record the resistance rating and any noted effects for each combination [1] [32] [29].

- Analyze Results and Select Material: Compare the results across all chemicals. A material rated "Excellent" for all chemicals is ideal. If no single material is excellent for all, prioritize based on the most aggressive chemical or choose the material with the least severe deleterious effect (e.g., minor discoloration may be more tolerable than severe corrosion) [1].

- Validate Selection: Before full implementation, conduct a long-term test by exposing the chosen component material to the chemical under actual process conditions and inspecting it for any signs of swelling, cracking, crazing, or corrosion [1].

Workflow Diagram

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details common materials used in the construction of automated liquid handlers and their functional properties related to chemical compatibility.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Property |

|---|---|

| PEEK (Polyetheretherketone) | A high-performance polymer with excellent chemical resistance to a wide range of organic and aqueous solutions, though it is not compatible with strong acids like sulfuric and nitric [1]. |

| PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene) | A very inert fluoropolymer known for its exceptional resistance to almost all chemicals, making it ideal for seals and tubing in aggressive solvent applications [1]. |

| Stainless Steel 316 (SS 316) | A corrosion-resistant metal alloy containing molybdenum, which provides superior resistance to salts and many biochemical buffers compared to other grades like SS 304 [1]. |

| FFKM (Perfluoroelastomer) | A synthetic rubber offering PTFE-like chemical resistance with the flexibility needed for high-performance seals and o-rings in demanding chemical environments [1]. |

| Ceramics | Used for components requiring excellent compatibility with detergents and reagents at elevated temperatures, where some metals may begin to fail [1]. |

Automated liquid handling systems are indispensable in modern laboratories, particularly in drug discovery and diagnostic testing, where they streamline processes, improve productivity, and ensure reproducibility [36] [37]. The reliability of these systems hinges on selecting the appropriate liquid handling technology, especially when working with diverse solvents and reagents. The core mechanical approaches for automated liquid handling are air displacement pipetting, positive displacement pipetting, and peristaltic pump-based dispensing [38]. Each technology has distinct strengths and limitations, making it suitable for specific applications and liquid types. This guide provides a detailed comparison, troubleshooting advice, and experimental protocols to help you select the optimal mechanism for your research, with a focus on solvent compatibility.

Technology Comparison and Selection Guide

The following diagram illustrates the operational principles and primary selection criteria for the three main liquid handling mechanisms.

Detailed Technical Comparison

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics and optimal use cases for each liquid handling technology to guide your selection.

| Feature | Air Displacement | Positive Displacement | Peristaltic Pump |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Principle | Piston moves an air cushion to aspirate/dispense [38] | Piston contacts liquid directly via disposable tip [38] | Rollers compress flexible tubing to create fluid motion [37] |

| Typical Volume Range | Microliters to milliliters [39] | Nanoliter to microliter volumes [38] | As low as 5 µL for bulk dispensing [37] |

| Best For Liquid Types | Aqueous solutions, buffers [38] | Viscous liquids (glycerol, oils), volatile solvents (DMSO, acetone) [38] | Corrosive chemicals, cell suspensions, continuous flow applications [38] |

| Solvent Compatibility Note | Not suitable for volatile or viscous liquids [39] | Excellent for volatile solvents and complex liquids [38] | Dependent on tubing material chemical resistance [1] [40] |

| Contamination Risk | Low (disposable tips) | Very low (disposable piston/tip) | Very low (fluid contacts only tubing interior) [40] |

| Precision (CV) | <5% for volumes >5 µL (aqueous) [38] | <5% for volumes >20 µL (viscous) [38] | Varies with tubing wear, pressure, and fluid properties [41] |

Solvent Compatibility and Material Selection

Chemical Compatibility Guide

Solvent compatibility is a critical factor in selecting and operating a liquid handling mechanism. Incompatible materials can lead to component degradation, leakage, and sample contamination [1].

- Air Displacement Pipetting: The main compatibility concern is the pipette tip material (often polypropylene). While resistant to many aqueous solutions, tips may not be suitable for aggressive organic solvents which can cause swelling or dissolution. System longevity can also be compromised by solvent vapors affecting internal components [39].

- Positive Displacement Pipetting: The disposable piston and tip, which are in direct contact with the liquid, are the primary concern. While better for harsh chemicals, you must still verify that the tip material is compatible with your specific solvents [38].

- Peristaltic Pumps: Compatibility is determined solely by the tubing material [40]. You must select tubing that is chemically resistant to the solvent being pumped. Common tubing materials include:

- Silicone: Good for many applications but not compatible with solvents like hexane or toluene.

- Tygon: A family of tubing with various formulations for different chemical resistances.

- Viton: Excellent for a wide range of solvents and aggressive chemicals [41].

Key Consideration: Chemical compatibility is rarely binary and can be influenced by concentration, temperature, and exposure time. A sodium hydroxide solution at 20% may be compatible with a material that is severely degraded by an 80% concentration [1]. Always consult a chemical compatibility chart from your component or tubing manufacturer before use.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Liquid Handling |

|---|---|

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | Common solvent for compound libraries; has higher viscosity and hygroscopicity, requiring slower pipetting speeds to avoid bubbles and volume inaccuracies [38]. |

| Glycerol | A model viscous liquid; handling requires significantly slowed aspiration/dispense speeds and positive displacement mechanisms for accuracy [38]. |

| Methanol/Acetone | Volatile solvents with high vapor pressure; require liquid class adjustments like extended delays, larger air gaps, and positive displacement tips to minimize evaporation and ensure accuracy [38]. |

| Detergent-based Buffers | Common in assays; can lower liquid surface tension, leading to dripping if standard aqueous liquid class parameters are used [38]. |

| Silicone, Viton, Tygon Tubing | Flexible tubing for peristaltic pumps; material selection is critical for chemical compatibility and preventing premature rupture or fluid contamination [41] [40]. |

Troubleshooting FAQs

Air Displacement Pipetting

Q: Our aqueous buffer transfers are consistently inaccurate and imprecise. What should we check?

- A: First, verify the liquid class parameters in your system software. A generic "water" class may not be optimal for buffers with additives like detergents. Check for tip seal integrity and ensure there are no obstructions or damage to the tips. Calibrate the instrument using a gravimetric method if inaccuracy persists [38] [37].

Q: We see bubbles or volume loss when pipetting volatile solvents like acetone. How can we fix this?

- A: This is a classic challenge for air displacement. The high vapor pressure of the solvent disrupts the air cushion. The most effective solution is to switch to a positive displacement system. If you must use an air displacement pipettor, optimize the liquid class by using a slower aspiration speed, a larger air gap, and extended pre- and post-dispense delays to allow pressure equilibrium [38].

Positive Displacement Pipetting

Q: Viscous liquids like glycerol are sticking to the disposable piston tip and not dispensing fully.

- A: Optimize the liquid class by significantly reducing the dispensing speed and implementing a "touch-off" function against the vessel wall to wipe the droplet. Increase the post-dispense delay to allow the fluid string to break cleanly. Using tips with a specialized coating can also help reduce adhesion [38].

Peristaltic Pumps

Q: The flow rate from our peristaltic pump is unstable or insufficient.

- A: This is a common issue with several potential causes. Follow this troubleshooting checklist [42] [41]:

- Inspect the pump tube: Check for wear, flattening, cracks, or leaks. Replace the tube if any damage is found.

- Check for blockages: Inspect the inlet and outlet lines for kinks or obstructions.

- Purge air from the system: Air entrapped in the tubing can cause pulsating flow. Run the pump at a low speed to purge air.

- Verify roller adjustment: Ensure roller pressure is correct according to the manufacturer's guidelines.

- Check pump speed: Ensure the pump speed setting is appropriate for the desired flow rate.

Q: Our pump tubing ruptures frequently, leading to leaks and downtime.

- A: Premature tube failure is often caused by one or more of the following [41]:

- Chemical Incompatibility: Verify that the tubing material is resistant to the solvent being pumped. Chemical degradation weakens the tube.

- Excessive Pressure: Check that the system pressure is within the tubing's rated limits.

- Operating at High Speeds: Running the pump at maximum speed for extended periods generates heat and accelerates tubing fatigue. Reduce the operating speed.

- Sharp Roller Edges: Inspect the rollers for wear or sharp edges that can cut the tube.

Experimental Protocols for Performance Verification

Gravimetric Method for Volume Verification

This protocol is used to assess the accuracy and precision of any liquid handling device.

- Principle: The mass of dispensed liquid is measured on a high-precision analytical balance and converted to volume using the liquid's density [37].

- Materials:

- Automated liquid handler (air displacement, positive displacement, or peristaltic pump)

- High-precision analytical balance (e.g., 0.1 mg readability)

- Suitable collection vessel (e.g., low-static microtube)

- Test liquid (e.g., distilled water for aqueous systems, or the specific solvent for compatibility testing)

- Temperature probe

- Procedure:

- Condition the test liquid and the environment to a stable temperature (e.g., 20°C - 25°C). Record the temperature.

- Tare the pre-cleaned, dry collection vessel on the balance.

- Program the liquid handler to dispense the target volume (

V_target) into the vessel. For a peristaltic pump, collect effluent for a timed interval. - Dispense the liquid. Record the mass (

m) displayed on the balance. - Repeat this process at least

n=10times for a robust statistical analysis.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the density (

ρ) of the liquid at the recorded temperature from standard tables. - Calculate the actual dispensed volume for each replicate:

V_actual = m / ρ. - Calculate the Accuracy as percent bias:

%Bias = [(Mean(V_actual) - V_target) / V_target] * 100[37]. - Calculate the Precision as percent coefficient of variation:

%CV = (Standard Deviation(V_actual) / Mean(V_actual)) * 100[37]. - For most applications, a bias below 5% and a CV below 10% are acceptable, though stricter limits apply for critical assays [37].

- Calculate the density (

Protocol for Optimizing a Liquid Class for a Volatile Solvent