Solving the Reproducibility Crisis in High-Throughput Screening: Strategies for Robust and Reliable Data

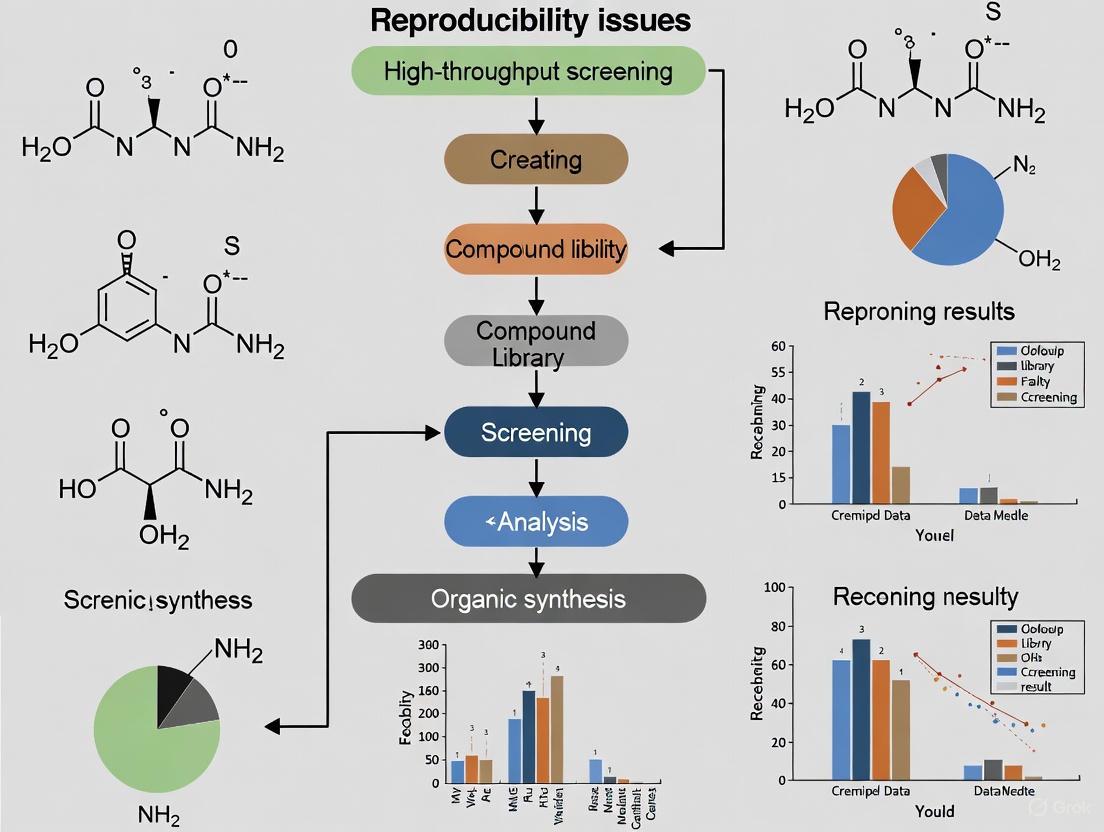

This article addresses the critical challenge of reproducibility in high-throughput screening (HTS), a cornerstone of modern drug discovery and biological research.

Solving the Reproducibility Crisis in High-Throughput Screening: Strategies for Robust and Reliable Data

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of reproducibility in high-throughput screening (HTS), a cornerstone of modern drug discovery and biological research. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive framework for understanding, mitigating, and validating HTS workflows to ensure data robustness. We first explore the foundational causes of irreproducibility, from technical variability to environmental factors. The discussion then progresses to methodological solutions, including advanced automation and rigorous assay design. A dedicated troubleshooting section offers practical optimization strategies, while the final segment details robust validation protocols and comparative analyses of technologies and reagents. By synthesizing these four intents, this guide empowers scientists to implement reproducible HTS practices, thereby accelerating the development of reliable scientific discoveries and therapeutics.

Understanding the Roots of Irreproducibility in HTS

Defining Reproducibility, Repeatability, and Reliability in an HTS Context

In modern drug discovery, High-Throughput Screening (HTS) serves as a critical tool for rapidly testing large libraries of chemical or biological compounds against specific therapeutic targets [1]. The core value of any HTS campaign lies in the confidence of its results, making reproducibility, repeatability, and reliability foundational concepts. These are not merely academic concerns; issues with reproducibility have reached alarming rates in preclinical research, with studies indicating that 50% to 80% of published results may not be reproducible [2]. This irreproducibility represents not just a scientific challenge but also a significant economic burden, estimated to account for approximately $28 billion in spent funding in the U.S. alone for preclinical research that cannot be reproduced [2].

Within the HTS workflow, these terms carry specific technical meanings. Reproducibility typically refers to the consistency of results across different replicates, experiments, or laboratories. Repeatability often concerns the consistency of measurements under identical, within-laboratory conditions. Reliability encompasses the overall trustworthiness of the data, indicating that results are robust, reproducible, and minimize false positives and negatives. Understanding and optimizing these parameters is essential because HTS activities consume substantial resources—utilizing large quantities of biological reagents, screening hundreds of thousands to millions of compounds, and employing expensive equipment [3]. Before embarking on full HTS campaigns, researchers must therefore validate their processes to ensure the quality and reproducibility of their outcomes [3].

Troubleshooting Guides for HTS Reproducibility

Addressing Variability and Human Error

Problem: High inter- and intra-user variability in manual processes leads to inconsistent results.

Solution: Implement automated workflows to standardize procedures.

- Liquid Handling Automation: Utilize non-contact dispensers and robotic systems to eliminate pipetting variability. Systems equipped with verification technology (e.g., DropDetection) can confirm that correct liquid volumes have been dispensed into each well, allowing errors to be identified and corrected [4].

- Assay Miniaturization: Transition to 384-well or 1536-well plates to reduce reagent consumption and variability while increasing throughput. This miniaturization can reduce reagent consumption and overall costs by up to 90% [4].

- Workflow Integration: Employ integrated robotic platforms that handle multiple plates consistently, reducing human intervention and associated errors [4] [5].

Validation Metric: Monitor the coefficient of variation (CV) across replicate wells. A CV below 10-15% typically indicates acceptable pipetting precision in automated systems.

Managing Missing Data and Dropouts

Problem: High levels of missing observations, common in techniques like single-cell RNA-seq, skew reproducibility assessments [6].

Solution: Apply statistical methods designed to handle missing data.

- Latent Variable Models: Use advanced statistical approaches like correspondence curve regression (CCR) with latent variables to incorporate information from missing values rather than excluding them [6].

- Threshold-Based Assessment: Evaluate consistency across a series of rank-based selection thresholds rather than relying solely on correlation measures that require complete data [6].

- Data Imputation Validation: When using imputation methods, validate them with pilot studies that intentionally mask known data points to assess imputation accuracy.

Validation Metric: Compare Spearman correlation with and without zero-count transcripts. Significant differences indicate potential missing data bias [6].

Overcoming Data Handling Challenges

Problem: Vast volumes of multiparametric data create analysis bottlenecks and obscure meaningful patterns.

Solution: Implement specialized HTS software and data management systems.

- Integrated HTS Platforms: Utilize software that combines assay setup, plate design, instrument integration, and downstream data analysis in a unified system [7].

- Automated QC Checks: Deploy AI-driven quality control systems that automatically flag outliers, technical errors, and plate-level artifacts [7].

- Standardized Analysis Pipelines: Develop consistent data normalization and transformation protocols that are applied across all screens to minimize analytical variability.

Validation Metric: Track Z'-factor across plates (0.5-1.0 indicates excellent assay robustness) [8]. Consistent Z' values indicate stable data quality.

Optimizing Assay Design and Validation

Problem: Poorly designed assays generate false positives and negatives, compromising reliability.

Solution: Implement rigorous assay development and validation protocols.

- Orthogonal Assays: Confirm primary screening hits using different detection technologies or assay formats to eliminate technology-specific artifacts [9].

- Counter-Screening: Identify and filter out compounds with undesirable mechanisms of action (e.g., auto-fluorescent compounds in fluorescence-based assays) [9].

- Pilot Studies: Conduct small-scale pilot experiments to validate assay performance before full implementation [9].

Validation Metric: Establish a multi-tiered confirmation cascade: primary screen → confirmatory screening → dose-response → orthogonal testing → secondary screening [9].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for HTS Assay Validation

| Metric | Target Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Z'-factor | 0.5 - 1.0 | Excellent assay robustness [8] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | >5 | Sufficient detection sensitivity [8] |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | <10-15% | Acceptable well-to-well precision |

| Signal Window | >2-fold | Adequate dynamic range [8] |

Statistical Assessment of Reproducibility

Reproducibility Indexes and Measures

Statistical assessment is crucial for quantifying HTS reproducibility. Multiple methods exist, each with strengths and limitations:

- Correspondence Curve Regression (CCR): This method models how the probability that a candidate consistently passes selection thresholds in different replicates is affected by operational factors. It evaluates reproducibility across a series of rank-based thresholds, providing a comprehensive view beyond single-threshold measures [6].

- Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR): A method that profiles how consistently candidates are ranked and selected in replicate experiments across a sequence of selection thresholds [6].

- Spearman/Pearson Correlation: Traditional measures of association between replicate measurements. However, these can yield conflicting results when missing data handling approaches differ, making them potentially misleading without complementary measures [6].

The following diagram illustrates the statistical assessment workflow for evaluating reproducibility in HTS:

Incorporating Missing Data in Reproducibility Assessment

Standard reproducibility measures often fail when substantial missing data exists due to underdetection, as commonly occurs in single-cell RNA-seq where many genes report zero expression levels [6]. A principled approach accounts for these missing values:

- Latent Variable Approach: Extends statistical models like CCR to incorporate candidates with unobserved measurements, providing more accurate reproducibility assessments [6].

- Comparative Analysis: Evaluate how different missing data treatments affect reproducibility conclusions. For example, in a study of HCT116 cells, TransPlex kits showed lower Spearman correlation (0.648) than SMARTer kits (0.734) when zeros were included, but the opposite pattern emerged when only non-zero transcripts were considered [6].

Table 2: Impact of Missing Data Handling on Reproducibility Metrics

| Analysis Method | TransPlex Kit | SMARTer Kit | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman (zeros included) | 0.648 | 0.734 | SMARTer more reproducible [6] |

| Spearman (non-zero only) | 0.501 (8,859 transcripts) | 0.460 (6,292 transcripts) | TransPlex more reproducible [6] |

| Pearson (zeros included) | Higher | Lower | TransPlex more reproducible [6] |

| Pearson (non-zero only) | Higher | Lower | TransPlex more reproducible [6] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the difference between reproducibility and repeatability in HTS?

A: In HTS context, repeatability typically refers to the consistency of results when the same experiment is performed multiple times under identical conditions (same operator, equipment, and short time interval). Reproducibility refers to the consistency of results when experiments are conducted under changing conditions (different operators, equipment, or laboratories) [3] [6]. Both are components of overall reliability, which encompasses the trustworthiness of data throughout the screening cascade.

Q2: How can we distinguish between true hits and false positives in HTS?

A: True hits can be distinguished through a multi-stage confirmation process: (1) Confirmatory screening retests active compounds using the same assay conditions; (2) Dose-response screening determines potency (EC50/IC50) across a concentration range; (3) Orthogonal screening uses different technologies to confirm target engagement; (4) Counter-screening identifies compounds with interfering properties; (5) Secondary screening confirms biological relevance in functional assays [9].

Q3: What are the most critical factors for achieving reproducible HTS results?

A: The most critical factors include: (1) Assay robustness with Z'-factor >0.5 [8]; (2) Automated liquid handling to minimize human error [4]; (3) Proper statistical handling of missing data [6]; (4) Standardized operating procedures across users and sites [4]; (5) Quality compound libraries with documented purity and solubility [9].

Q4: How does automation specifically improve HTS reproducibility?

A: Automation enhances reproducibility by: (1) Reducing human error in repetitive tasks; (2) Standardizing liquid handling across users and experiments; (3) Enabling miniaturization which reduces reagent-based variability; (4) Providing verification features (e.g., drop detection) to confirm proper dispensing [4].

Q5: What statistical measures are most appropriate for assessing HTS reproducibility?

A: The appropriate measure depends on your data characteristics: (1) Correspondence curve methods are ideal for rank-based data with multiple thresholds [6]; (2) Z'-factor assesses assay robustness (0.5-1.0 indicates excellent assay) [8]; (3) Correlation coefficients (Spearman/Pearson) are common but can be misleading with missing data [6]; (4) CV (coefficient of variation) measures precision across replicates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTS Reproducibility

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Reproducibility Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Contact Liquid Handlers | Precise reagent dispensing without cross-contamination | Drop detection technology verifies dispensed volumes [4] |

| 384-/1536-Well Microplates | Miniaturized assay formats | High-quality plates with minimal well-to-well variability ensure consistent results [5] |

| Validated Compound Libraries | Collections of chemically diverse screening compounds | Well-curated libraries with known purity and solubility reduce false results [9] |

| Transcreener ADP² Assay | Universal biochemical assay for multiple targets | Flexible design allows testing multiple targets with same detection method [8] |

| Cell Line Authentication | Verified cellular models for screening | Authenticated, low-passage cells ensure physiological relevance and consistency [5] |

| QC-Ready Detection Reagents | Fluorescence, luminescence, or absorbance detection | Interference-resistant readouts minimize false positives [8] |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Reproducibility Assessment Framework

Step-by-Step Methodology

To systematically evaluate and improve reproducibility in your HTS workflow, follow this detailed protocol:

Assay Development and Miniaturization

- Develop your assay in a 96-well format first, optimizing biological and detection parameters.

- Miniaturize to 384-well or 1536-well format, maintaining key performance metrics (Z' > 0.5, signal-to-noise > 5) [8].

- Validate miniaturized assay with positive and negative controls across at least 3 independent runs.

Automated Workflow Implementation

- Program liquid handlers for consistent reagent dispensing across all plates.

- Implement real-time dispensing verification if available (e.g., DropDetection technology) [4].

- Establish standardized plate handling procedures to minimize edge effects and evaporation.

Pilot Screening and Statistical Power Analysis

- Conduct a pilot screen with 5-10% of the compound library in replicate.

- Calculate statistical power and determine appropriate replicate number based on effect size and variability.

- Use correspondence curve regression or similar methods to assess preliminary reproducibility [6].

Full-Scale Screening with Embedded Controls

- Distribute positive and negative controls across all plates to monitor inter-plate variability.

- Include randomized compound placement to avoid positional bias.

- Implement periodic quality checks with standardized acceptance criteria.

Data Analysis and Hit Confirmation

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comprehensive HTS process with quality control checkpoints:

This experimental protocol emphasizes continuous quality monitoring at each stage, enabling researchers to identify and address reproducibility issues proactively throughout the HTS campaign.

Troubleshooting Guides

Instrumentation and Data Quality Control

Issue: How can I identify systematic spatial artifacts in my high-throughput screening (HTS) plates that traditional quality control methods miss?

Traditional control-based quality control (QC) metrics like Z-prime (Z'), SSMD, and signal-to-background ratio (S/B) are industry standards but have a fundamental limitation: they can only assess the fraction of the plate containing control wells and cannot detect systematic errors affecting drug wells [10]. These undetected spatial artifacts—such as evaporation gradients, systematic pipetting errors, temperature-induced drift, or column-wise striping—can significantly compromise data reproducibility [10].

Solution: Implement the Normalized Residual Fit Error (NRFE) metric alongside traditional QC methods. NRFE evaluates plate quality directly from drug-treated wells by analyzing deviations between observed and fitted dose-response values, accounting for response-dependent variance [10].

Protocol for NRFE-based Quality Control:

- Perform Dose-Response Experiment: Conduct your HTS experiment as planned, ensuring drug treatments span multiple concentrations.

- Calculate Traditional QC Metrics: Compute Z-prime (Z' > 0.5), SSMD (>2), and S/B ratio (>5) from control wells to capture assay-wide technical issues [10].

- Fit Dose-Response Curves: Generate fitted dose-response curves for all compounds on the plate.

- Compute NRFE: Calculate the NRFE metric, which is based on the deviations (residuals) between the observed data points and the fitted curve, normalized by a binomial scaling factor [10].

- Apply Quality Thresholds: Use the following tiered system to classify plate quality [10]:

- NRFE < 10: Acceptable quality.

- NRFE 10-15: Borderline quality; requires additional scrutiny.

- NRFE > 15: Low quality; exclude from analysis or carefully review.

Plates flagged by high NRFE exhibit substantially lower reproducibility among technical replicates. Integrating NRFE with traditional QC can improve cross-dataset correlation and overall data reliability [10].

Reagent Variability and Quality Assurance

Issue: How do I mitigate lot-to-lot variance (LTLV) in immunoassays and other reagent-dependent assays?

Lot-to-lot variance is a significant challenge, negatively impacting assay accuracy, precision, and specificity. It is estimated that 70% of an immunoassay's performance is attributed to the quality of raw materials, while the remaining 30% depends on the production process [11]. Fluctuations in key biologics like antibodies, antigens, and enzymes are primary contributors.

Solution: Implement rigorous quality control and validation procedures for all critical reagents.

Protocol for Managing Reagent LTLV:

- Thorough Reagent Evaluation: Before adopting a new reagent lot, assess its critical quality attributes.

- For Antibodies and Antigens: Evaluate activity, concentration, affinity, specificity, purity, and stability. Use SDS-PAGE, SEC-HPLC, or capillary electrophoresis to check for aggregates and impurities, which can cause high background or inaccurate readings [11].

- For Enzymes (e.g., HRP, ALP): Confirm enzymatic activity units, not just purity. Be aware that purity of 90-95% is often acceptable, but the biological activity of impurities can vary [11].

- Perform Bridging Experiments: When a new lot is received, run parallel assays using both the old and new lots on the same set of characterized samples. This directly compares performance and identifies any significant shift in results.

- Use a Master Calibrator and QC Panel: Maintain a stable, well-characterized master calibrator and quality control panel to benchmark the performance of new reagent lots against a consistent standard [11].

- Document Everything: Keep detailed records of all reagent lots, including certificates of analysis, quality control data, and performance validation results from bridging studies.

Environmental Factors and Laboratory Conditions

Issue: What are the primary environmental factors that introduce variability, and how can they be controlled?

Laboratories are sensitive environments where minor variations in conditions can dramatically affect experimental outcomes, sample integrity, and instrument performance [12]. Key factors include temperature, humidity, air quality, and physical disturbances like vibration and noise.

Solution: Proactively monitor and control the laboratory environment using appropriate instruments and established protocols.

Protocol for Environmental Monitoring and Control:

- Temperature: Maintain a general lab temperature of 20–25°C (68–77°F), with tighter control for specific applications. Use digital temperature monitors with alarms to track conditions in the lab, as well as in refrigerators, incubators, and other storage units [12].

- Humidity: Control relative humidity between 30-50% to prevent microbial growth and corrosion (high humidity) or static electricity buildup (low humidity). Use hygrometers to monitor levels and employ dehumidifiers or humidifiers as needed [12].

- Air Quality: Ensure adequate ventilation, typically 6-12 air changes per hour, to protect against contaminants. Use high-efficiency air filters and monitor air quality with meters that can detect CO2 and other particulates [12].

- Pipette Performance: Account for environmental effects on liquid handling, which is a major source of error.

- Altitude/Barometric Pressure: Pipettes under-deliver at high altitudes due to lower air density. Calibrate pipettes in the environment where they are used, or adjust the delivery setting to compensate for the repeatable error [13].

- Thermal Disequilibrium: Pipettes over-deliver cold liquids and under-deliver warm liquids. To minimize error, pre-equilibrate liquids and pipettes to the same temperature, minimize the time the tip is exposed to a different temperature, and pipette close to the maximum volume where practical [13].

The following table summarizes the impact of these factors and solutions:

| Environmental Factor | Impact on Experiments | Ideal Range | Control Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Alters reaction rates; degrades samples; affects instrument calibration [12]. | 20–25°C (68–77°F) [12] | Digital temperature monitors; calibrated storage units [12]. |

| Humidity | Causes sample contamination/corrosion (high); static electricity (low) [12]. | 30-50% Relative Humidity [12] | Hygrometers; dehumidifiers/humidifiers; desiccants for storage [12]. |

| Air Quality | Leads to sample contamination; equipment damage; health hazards [12]. | 6-12 air changes/hour [12] | High-efficiency air filters; air quality meters (CO2, particles) [12]. |

| Pipetting (Altitude) | Volume under-delivery at high altitude [13]. | N/A | Calibrate pipettes in-lab; adjust delivery settings [13]. |

| Pipetting (Liquid Temp.) | Over-delivery of cold liquid; under-delivery of warm liquid [13]. | Liquid temp. = Pipette temp. | Pre-equilibrate liquids; use rapid, consistent technique [13]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: My experimental results are inconsistent between replicates. What should be my first step in troubleshooting? A: The first step is often to repeat the experiment. Simple, unintentional mistakes can occur. If the problem persists, systematically review your assumptions, methods, and controls. Ensure all equipment is calibrated, reagents are fresh and stored correctly, and you have included appropriate positive and negative controls [14] [15].

Q: I have a dim fluorescent signal in my immunohistochemistry experiment. What are the most common causes? A: A dim signal could indicate a problem with the protocol, but also consider the biological context—the protein may simply not be highly expressed in that tissue. Technically, check that your reagents have not degraded, your primary and secondary antibodies are compatible, and you have not over-fixed the tissue or used antibody concentrations that are too low. Change one variable at a time, starting with the easiest, such as adjusting microscope settings [14].

Q: How can I improve the overall reproducibility of my high-throughput screening process? A: Beyond specific troubleshooting, focus on process validation. Before a full HTS campaign, run a validation study to optimize the workflow and statistically evaluate the assay's ability to distinguish active from non-active compounds robustly. Utilize a variety of reproducibility indexes to benchmark performance [3].

Q: What is the most overlooked source of pipetting error? A: Thermal disequilibrium—pipetting liquids that are at a different temperature than the pipette itself—is a major and often overlooked source of error that can cause over- or under-delivery by more than 30%. Always equilibrate your liquids and pipette to room temperature for critical volume measurements [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Antibodies | Specific detection of target proteins or analytes in assays. | Monitor for aggregates and impurities via SEC-HPLC; test for activity and specificity with each new lot [11]. |

| Characterized Antigens | Serve as calibrators, controls, or targets in immunoassays. | Assess purity (e.g., via SDS-PAGE) and stability; ensure appropriate storage buffers are used [11]. |

| Enzymes (HRP, ALP) | Used as labels for detection in colorimetric, fluorescent, or chemiluminescent assays. | Quality should be measured in activity units, not just purity; source from reliable manufacturers [11]. |

| Assay Buffers & Diluents | Provide the chemical environment for the reaction. | Must be mixed thoroughly; variations in pH or conductivity can significantly affect assay performance [11]. |

| Solid Phases (Microplates, Magnetic Beads) | Provide the solid support for assay reactions. | Ensure consistency in coating, binding capacity, and low non-specific binding across lots [11]. |

Experimental Workflow and Troubleshooting Logic

The following diagram illustrates a systematic workflow for troubleshooting experiments, integrating checks for instrumentation, reagents, and environmental factors.

Quality Control Integration in HTS

This diagram shows how different quality control methods provide complementary oversight in high-throughput screening.

FAQs: Photoreactor Design and Reproducibility

Q1: Why is my photocatalytic reaction failing when I follow a published procedure exactly?

A: Even with identical chemical ingredients, small changes in your physical setup can cause failure. Key parameters often omitted from publications include [16] [17]:

- Photon Flux and Spectrum: The light source's intensity (W/m²) and spectral output (peak wavelength & FWHM) are critical but rarely fully characterized in methods sections [16] [17].

- Reaction Temperature: Light sources emit heat, and internal photochemical processes can significantly raise the reaction mixture's temperature, leading to unproductive side reactions. Reported cooling methods (e.g., "a fan was used") are often insufficient; the internal reaction temperature is what matters [16] [17].

- Vessel Geometry and Irradiation Path Length: Due to the high extinction coefficients of photocatalysts, light often penetrates only the first few millimeters of the reaction mixture. The vessel's shape and diameter dramatically affect how much reaction volume is effectively irradiated [16] [17].

Q2: What are the advantages of commercial photoreactors over homemade setups?

A: Commercial reactors are engineered to control the variables that undermine reproducibility [18] [19]:

- Uniform Irradiation: They provide even, consistent light distribution to all samples, which is extremely difficult to achieve with homemade LED arrays [18] [19].

- Integrated Temperature Control: They actively manage the heat generated by the light source, maintaining a consistent temperature across all reaction vessels [18].

- Standardized Geometry: They fix the distance between the light source and the reaction vial, a key variable affecting light intensity [16] [18].

- Safety and Ease of Use: They incorporate safety features (e.g., interlock switches) and are designed for user-friendly operation [19].

Q3: How can I improve reproducibility in high-throughput photocatalysis screening?

A: The core challenge is ensuring uniform conditions across all positions in a parallel reactor [16].

- Validate Your Reactor: Perform a "homogeneity test" by running the same model reaction in every well of the plate and analyzing the outcomes. Significant variations indicate underlying problems with light or temperature uniformity [16].

- Control Stirring/Shaking: Efficient and consistent mixing is crucial to overcome mass transfer limitations and ensure all reaction volume is exposed to light [16].

- Report Specifications: When publishing, include the technical specs of the parallel photoreactor and the results of uniformity tests. This provides immense value to the community [16].

Q4: My reaction works well in batch but fails during scale-up in flow. What could be wrong?

A: While flow reactors often provide superior irradiation, new failure points emerge [16] [17]:

- Fraction Collection Timing: In flow chemistry, the product is collected over time. If collection occurs outside the window of "steady-state" conditions, the product can be diluted, leading to highly variable results and yields [16] [17].

- Irradiation Path Length: Simply scaling a flow reaction by increasing the reactor diameter can be detrimental because light cannot penetrate as deeply into the center of the wider tube, leaving some substrate unreacted [16] [17].

Troubleshooting Guide

This guide helps diagnose and solve common photoreproducibility issues.

Table: Troubleshooting Photochemical Reactions

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low or inconsistent yield between identical runs | Inhomogeneous irradiation; Inconsistent temperature; Poor mass transfer | Use a reactor with even light distribution and active cooling; Ensure efficient stirring; Characterize light source intensity and spectrum [16] [18] [17]. |

| Reaction works in a small vial but fails upon scaling up | Increased irradiation path length; Inefficient light penetration | Switch to a continuous flow reactor or a scaled batch reactor designed to maintain a short light path length [16] [17] [19]. |

| Variable results across positions in a parallel reactor | Non-uniform light field across the plate; Position-dependent temperature differences | Validate reactor homogeneity by running the same reaction in every well; Use a reactor designed for uniform parallel processing [16]. |

| Formation of different or unexpected byproducts | Uncontrolled temperature leading to thermal side reactions | Implement better temperature control of the reaction mixture itself, not just the reactor block [16] [17]. |

| Reaction fails to reproduce a literature procedure | Undisclosed critical parameter (e.g., photon flux, vial type, distance to light source) | Consult literature on reproducibility; Contact the original authors for details; Use a standardized, well-characterized commercial reactor [16] [18] [17]. |

Experimental Protocols for Ensuring Reproducibility

Protocol 1: Validating Homogeneity in a Parallel Photoreactor

Purpose: To verify that all reaction positions within a high-throughput photoreactor experience identical conditions, ensuring data robustness [16].

Materials:

- Parallel photoreactor (e.g., EvoluChem PhotoRedOx Box, Illumin8) [18] [19].

- Standardized reaction vial type (e.g., 2 mL HPLC vials).

- Model photochemical reaction mixture (e.g., Photomethylation of buspirone) [18].

Methodology:

- Preparation: Prepare a large, homogeneous master mix of your model reaction.

- Loading: Dispense equal aliquots of the reaction mixture into vials and place them in every available position of the reactor.

- Irradiation: Run the photochemical reaction for a set time that achieves moderate conversion (e.g., 30-70%). This helps identify kinetic differences more clearly than at full conversion [16].

- Analysis: Quench and analyze each reaction vial using a standardized quantitative method (e.g., UPLC, GC).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the average conversion and the standard deviation across all positions.

Interpretation: A low standard deviation (e.g., ±2% as demonstrated in one study [18]) indicates a homogeneous reactor. Significant outliers or trends across the plate flag issues with light or temperature uniformity [16].

Protocol 2: Characterizing a Photochemical Reaction for Publication

Purpose: To document all critical parameters required for another lab to successfully reproduce a photochemical reaction.

Materials:

- Photoreactor

- Light meter (for intensity)

- Spectrometer (for emission spectrum)

- Temperature probe (for internal reaction temperature)

Methodology: Report the following parameters in the experimental section [16] [17]:

- Light Source: Manufacturer, model, and wavelength (e.g., "Kessil PR160L 440 nm"). Include the spectral output (peak & FWHM) and optical power or intensity (W/m² or mW/cm²) at the reaction vessel.

- Reactor Setup: Type (batch/flow), manufacturer, and model. For batch, specify the vessel type (e.g., "20 mL scintillation vial"), material (e.g., "borosilicate glass"), and the distance from the light source.

- Temperature Control: Method of cooling (e.g., "cooling fan") and, crucially, the measured temperature of the reaction mixture during irradiation.

- Mixing: Stirring speed (RPM) or shaking frequency.

- Atmosphere: Reaction atmosphere (e.g., "degassed with N₂ for 5 minutes" or "sealed under air").

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table: Key Components for Reproducible Photocatalysis

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized LED Light Source | Provides photons to excite the photocatalyst. | Narrow emission band (FWHM), stable power output, commercial availability. Wavelength and intensity must be reported [16] [17] [19]. |

| Photocatalyst (e.g., Ir(dF(CF₃)ppy)₂(dtbpy)PF₆) | Absorbs light and mediates electron transfer events. | Should be commercially available or easily synthesized. High purity is essential [18] [17]. |

| Temperature-Controlled Photoreactor | Houses the reaction and manages heat. | Active cooling (e.g., Peltier, fan), even light distribution, and compatibility with standard vial formats [18] [19]. |

| Vial Set (0.3 mL to 20 mL) | Holds the reaction mixture. | Material (e.g., glass transmissivity), geometry, and sealing method can impact the reaction [18]. |

| Inert Atmosphere System | Controls the reaction environment. | Prevents inhibition by oxygen or other atmospheric gases. Details on degassing procedure should be reported [16] [17]. |

Supporting Diagrams

Diagram: Troubleshooting Photoreproducibility Workflow

Diagram: Protocol for Reactor Validation

Why Biological Complexity and Unique Dataset Patterns Challenge Validity

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What are the most common sources of poor reproducibility in high-throughput behavioral screens? A: The primary sources are often biological and technical. Biologically, slight variations in organism health, age synchronization, or culture conditions can introduce significant noise. Technically, insufficient statistical power from low replicate numbers, over-reliance on manual feature selection, and assays that are not robust enough for automation can lead to findings that fail to validate [20].

Q: How can I make the data visualizations from my screening results accessible and interpretable for all team members? A: Adopt accessible data visualization practices. This includes providing a text summary of the key trends, ensuring a contrast ratio of at least 3:1 for graphical elements and 4.5:1 for text, and not using color as the only way to convey information. Supplement charts with accessible data tables and use simple, direct labeling instead of complex legends [21] [22] [23].

Q: Our AI models identify promising compounds, but they often fail in subsequent biological validation. Are we using the wrong models? A: Not necessarily. This often highlights a disconnect between the computational prediction and biological reality. AI models are only as good as the data they are trained on. The failure may stem from a lack of robust, physiologically relevant functional assay data to train the models effectively. AI-generated "informacophores" must be rigorously validated through empirical biological assays to confirm therapeutic potential [24].

Q: Why would a machine learning model outperform traditional statistical methods in analyzing complex phenotypic data? A: Traditional statistical methods, like t-tests with multiple comparison corrections, can have low statistical power for detecting subtle, non-linear patterns. They generate binary results (significant/not significant) and are designed for linear relationships. Machine learning models, such as Random Forests, can capture these complex, non-linear interactions between multiple features, providing a more quantitative and robust measure of treatment effects [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Variability in Model Organism Behavior

Issue: Your C. elegans or other model organism screens show high levels of behavioral variability, making it difficult to distinguish true treatment effects from noise.

Solution:

- Standardize Culture Conditions: Implement strict protocols for organism age synchronization, temperature, and food source to minimize pre-analytical variability.

- Increase Replication: Ensure an adequate number of biological replicates are used to account for inherent biological variation. Do not rely on a small number of wells or plates.

- Automate Data Collection: Use automated tracking platforms (e.g., Tierpsy Tracker) to reduce observer bias and consistently extract a large number of morphological and movement features [20].

- Validate with ML: Train a machine learning classifier (e.g., Random Forest) to distinguish between control and disease-model strains as a quality control step before proceeding with drug screening. A high-performing model confirms that the phenotypic difference is detectable [20].

Problem: Inaccessible or Misleading Data Visualizations

Issue: Colleagues or reviewers misinterpret your charts, or the charts are not accessible to individuals with color vision deficiencies.

Solution:

- Provide Multiple Formats: Always accompany a chart with a text summary describing the key trends and a link to an accessible data table [21] [22].

- Check Contrast: Use tools like the WebAIM Contrast Checker to ensure all elements meet WCAG guidelines: at least 3:1 for graphics and 4.5:1 for text [22] [23].

- Go Beyond Color: Use a combination of color, patterns, shapes, and direct data labels to convey information. This ensures understanding is not dependent on color perception alone [21] [25].

- Use Accessible Palettes: When building custom tools, leverage established, accessible color palettes from libraries like D3.js (e.g.,

schemeDark2,schemeSet3) which are designed for categorical differentiation [26] [27].

Problem: Translating AI-Hit Compounds to Biologically Relevant Leads

Issue: Compounds identified through AI-powered virtual screening do not show efficacy in functional biological assays.

Solution:

- Focus on Data Quality: "Garbage in, garbage out" is a key principle. AI models require high-quality, well-annotated training data. Invest in generating robust biological assay data with complete metadata [28] [24].

- Implement a Feedback Loop: Create an iterative cycle where AI predictions are validated through wet-lab experiments, and the experimental results are fed back to refine and retrain the AI models [24].

- Use Relevant Assays: Employ biologically relevant functional assays (e.g., high-content screening, 3D cell cultures) that can capture complex phenotypic changes and provide a more translational readout [24].

- Prioritize Explainability: Where possible, use machine learning models that offer some level of interpretability (e.g., Random Forest) to understand which features are driving the predictions, or use hybrid models that combine AI with medicinal chemistry intuition [20] [24].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Machine Learning-Based Phenotypic Screening Protocol

This protocol outlines a method for using machine learning to analyze high-throughput behavioral data from C. elegans, offering a more sensitive alternative to traditional statistical tests [20].

Strain Preparation & Video Acquisition:

- Culture control (e.g., N2) and disease-model strains of C. elegans under standardized conditions.

- For drug screening, treat disease-model worms with compounds from your library.

- Using an automated capture system, record videos of worms in multi-well plates. Include a period with a specific stimulus (e.g., blue light pulses) to elicit measurable behavioral responses.

Feature Extraction:

- Process the videos using tracking software like Tierpsy Tracker.

- The software will extract a large set of quantitative features for each worm trajectory, including speed, morphology (length, curvature), and movement patterns.

- Average the features from all trajectories within a single well to generate a single feature vector per well.

Model Training & Validation:

- Use the feature vectors from control and disease-model strains (untreated) to train a classifier, such as a Random Forest.

- Reserve a portion of this data as a validation set to confirm the model can accurately distinguish between the two strains.

Drug Efficacy Scoring (Recovery Index):

- Input the feature vectors from drug-treated disease-model worms into the trained classifier.

- Use the classifier's output confidence score as a Recovery Index. A higher confidence score assigned to the "control" class indicates a stronger treatment effect, representing the percentage of phenotypic recovery towards the wild-type state.

Quantitative Data from ML vs. Statistical Methods

The table below summarizes a comparison of approaches for analyzing a drug repurposing screen in C. elegans, highlighting the advantages of ML [20].

| Method | Number of Features Analyzed | Key Limitation | Result on Test Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Statistics (Block permutation t-test) | 3 core features selected manually | Low power after multiple-test correction; fails to detect subtle, non-linear patterns. | No hits detected when analysis was expanded to 256 features. |

| Machine Learning (Random Forest) | All 256 features simultaneously | Higher computational cost; requires careful validation to prevent overfitting. | Identified compounds with a significant recovery effect by capturing complex patterns. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and tools for implementing a robust, high-throughput screening pipeline.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Tierpsy Tracker | Open-source software used to automatically track worms in videos and extract a high-dimensional set of morphological and movement-related features [20]. |

Accessible Color Palettes (e.g., D3 schemeDark2) |

Pre-defined sets of colors that ensure sufficient contrast and are distinguishable to users with color vision deficiencies, improving chart clarity [26] [23]. |

| C. elegans Disease Models | Genetically modified worms (e.g., via CRISPR/Cas9) to carry mutations homologous to human diseases, providing a cost-effective in vivo model for screening [20]. |

| Functional Assays | Wet-lab experiments (e.g., enzyme inhibition, cell viability) that are essential for empirically validating the therapeutic activity predicted by AI models [24]. |

| Random Forest Classifier | A machine learning algorithm that is particularly effective for phenotypic data due to its ability to handle non-linear relationships and provide feature importance scores for interpretability [20]. |

Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

The High Cost of Irreproducible Results in Drug Discovery Timelines

Your Technical Support Center: Ensuring Reproducibility in HTS

This technical support center is designed to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals identify, troubleshoot, and prevent common issues that lead to irreproducible results in high-throughput screening (HTS). The following guides and FAQs are framed within the broader thesis that addressing reproducibility is critical for protecting the substantial investments in HTS campaigns, which involve large quantities of biological reagents, hundreds of thousands of compounds, and the utilization of expensive equipment [29].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common sources of irreproducibility in an HTS workflow? Irreproducibility often stems from process-related errors rather than the biological question itself. Key areas to investigate include:

- Liquid Handling Inaccuracy: Improperly calibrated pipettes or dispensers can lead to inconsistent reagent or compound volumes across assay plates, causing significant well-to-well variation [29].

- Cell Line Instability: Using cells with high passage numbers or that are not properly authenticated can lead to genetic drift and changes in phenotypic response [29].

- Reagent Degradation: Improper storage or use of reagents beyond their stability period can reduce assay signal and increase background noise [29].

- Environmental Fluctuations: Uncontrolled factors like ambient temperature, CO₂ levels, and humidity during cell culture or assay incubation can alter results [3].

2. How can I quickly validate that my HTS process is reproducible before a full-scale screen? Before embarking on a full HTS campaign, it is essential to conduct a process validation. This involves:

- Running a Pilot Screen: Perform a smaller-scale screen using a representative subset of compounds and the complete planned workflow [29].

- Calculating Reproducibility Indexes: Use statistical measures to evaluate the results. For example, you can calculate the Z'-factor to assess the assay's robustness and signal-to-noise window. Other indexes, adapted from medical diagnostics, can be used to gauge the ability to distinguish active from non-active compounds reliably [29] [3].

3. Our negative controls are showing high signal, leading to a low signal-to-background ratio. What should I check? A high background signal in negative controls is a common troubleshooting issue. Follow this isolation process:

- Confirm Reagent Purity: Check for contamination in your buffer or media.

- Inspect Washing Steps: Ensure that aspiration/washing steps are thorough and consistent across all plates to remove unbound reagents.

- Check Substrate Specificity: Verify that your detection substrate (e.g., in a luciferase assay) is not reacting non-specifically.

- Test Individual Components: Systematically remove or replace individual assay components (e.g., the enzyme, substrate, or cell lysate) to identify the source of the background [30] [31].

4. We are seeing high well-to-well variation within the same assay plate. What is the likely cause? High intra-plate variation often points to a problem with liquid handling.

- Primary Cause: Check for clogged or poorly calibrated tips on your automated liquid handler. Perform a gravimetric analysis to check dispensing accuracy and precision.

- Secondary Cause: Ensure cells are evenly suspended and seeded at a consistent density across the entire plate. Aggregated cells can lead to uneven responses [29] [32].

5. A previously identified 'hit' compound fails to show activity in follow-up experiments. How should I investigate? This is a classic irreproducibility problem. Your investigation should focus on two areas:

- Compound Integrity: Re-test the original sample for purity and stability. Check for precipitation or degradation due to improper storage (e.g., repeated freeze-thaw cycles, exposure to light).

- Assay Conditions: Meticulously compare all experimental parameters between the original and follow-up experiments. Small differences in cell passage number, serum batch, incubation time, or reagent supplier can be the root cause [29] [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing a Failed HTS Pilot Screen

When a pilot screen fails to meet quality control standards (e.g., Z'-factor < 0.5), use this structured approach to diagnose the problem [30] [31].

Process:

Guide 2: Systematic Approach to Resolving Irreproducible Results Between Runs

For when you get conflicting results from the same experiment performed on different days [30] [31].

Process:

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Key Reproducibility Metrics for HTS Process Validation

Before any full-scale screen, validate your process using these key metrics on a pilot run [29] [3].

| Metric | Calculation Formula | Target Value | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z'-Factor | `1 - [ (3σc⁺ + 3σc⁻) / | μc⁺ - μc⁻ | ]` | > 0.5 |

Measures the assay's robustness and quality. An excellent assay window. |

| Signal-to-Background (S/B) | μ_c⁺ / μ_c⁻ |

> 10 (or context-dependent) |

The ratio of positive control signal to negative control signal. | ||

| Signal-to-Noise (S/N) | (μ_c⁺ - μ_c⁻) / √(σ_c⁺² + σ_c⁻²) |

> 10 (or context-dependent) |

Indicates how well the signal can be distinguished from experimental noise. | ||

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | (σ / μ) * 100% |

< 10-20% (depending on assay) |

Measures the dispersion of data points in a set of replicates. |

Protocol: HTS Process Validation

- Plate Design: Include at least 32 wells each of positive and negative controls on every 384-well assay plate. Distribute them evenly across the plate to monitor spatial bias [29].

- Pilot Run: Execute a screen of at least 3-5 plates using the full automation system and a small, diverse compound library (e.g., 1,000-5,000 compounds) [29].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the metrics in the table above for each plate. Any plate failing the Z'-factor target should be flagged, and the root cause investigated before proceeding [29] [3].

- Reproducibility Assessment: If possible, repeat the pilot run on a different day with a fresh preparation of key reagents. Compare the hit lists and potency rankings to assess inter-run reproducibility [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and their functions for ensuring reproducible HTS experiments.

| Item | Function in HTS | Key Consideration for Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Cell Line | Biological system for phenotypic or target-based screening. | Use low passage stocks, regularly authenticate (e.g., STR profiling), and test for mycoplasma [29]. |

| Reference Agonist/Antagonist | Serves as the positive control for each assay plate. | Use a chemically stable compound with known, potent activity. Prepare fresh aliquots to avoid freeze-thaw cycles [29]. |

| Assay-Ready Plates | Source plates containing pre-dispensed compounds. | Ensure compound solubility and stability in DMSO over time. Store plates in sealed, humidity-controlled environments [29]. |

| Validated Antibody/Probe | Detection reagent for quantifying the assay signal. | Validate specificity and lot-to-lot consistency. Titrate to determine the optimal concentration for signal-to-background [29]. |

| Cell Viability Assay Kit | Counterscreen to rule out cytotoxic false positives. | Choose a kit that is non-toxic, homogenous, and compatible with your primary assay readout [32]. |

Implementing Robust HTS Workflows and Technologies

Strategic Assay Development and Plate Design to Minimize Systematic Error

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Systematic Spatial Artifacts

Problem: Data shows unexplained patterns (e.g., edge effects, column-wise striping) that compromise reproducibility, even when traditional quality control metrics like Z'-factor appear acceptable.

Explanation: Spatial artifacts are systematic errors caused by uneven physical conditions across the assay plate. These can include evaporation gradients (edge effects), temperature fluctuations during incubation, or liquid handling inconsistencies. Traditional control-based metrics often fail to detect these issues because control wells only sample a limited portion of the plate [10].

Solution: Implement a dual-approach quality control strategy that combines traditional metrics with spatial artifact detection.

Step 1: Visual Inspection of Plate Heatmaps

- Generate a heatmap of the raw data from a control plate to visually identify patterns like strong edge effects or column/row striping.

- Protocol: Run a control plate with a uniform sample and create a heatmap where the color of each well represents its signal intensity. Patterns indicate systematic spatial artifacts.

Step 2: Apply Normalized Residual Fit Error (NRFE) Analysis

- Use the NRFE metric to quantitatively identify systematic errors in drug-treated wells that are missed by control-based metrics [10].

- Protocol: After fitting dose-response curves, calculate the NRFE. An NRFE value >15 indicates low-quality data that should be excluded or carefully reviewed. Values between 10-15 require additional scrutiny. This method is available through the

plateQCR package [10].

Step 3: Mitigate Identified Artifacts

- For edge effects, use specialized plate sealants or humidified incubators [33].

- For liquid handling errors, recalibrate instruments and ensure proper maintenance.

Guide 2: Addressing Poor Assay Robustness

Problem: The assay has a low Z'-factor or shows high variability between replicate plates, leading to an inability to distinguish true hits from background noise.

Explanation: Assay robustness is the ability to consistently detect a real biological signal. A low Z'-factor can stem from high variability in controls, a weak signal window, or temporal drift (degradation of reagents or instrument performance over time) [34] [33].

Solution: Optimize controls and validate assay performance over time.

Step 1: Select Appropriate Controls

- Use controls that reflect the strength of the hits you hope to find, not just the strongest possible effect. Consider using decreasing doses of a strong control to gauge sensitivity to realistic hits [34].

- Strategically place controls to minimize spatial bias; alternate positive and negative controls across available columns and rows instead of clustering them on the plate's edge [34].

Step 2: Perform Plate Drift Analysis

- This detects systematic temporal errors, such as reagent degradation or instrument warm-up effects, that can cause signals to drift from the first plate to the last in a screening run [33].

- Protocol: Run a series of identical control plates over the expected duration of your screening campaign. Plot the key performance metrics (e.g., Z'-factor, S/B) for each plate over time. A significant downward trend indicates plate drift.

Step 3: Optimize Replicate Strategy

- For complex phenotypes, more replicates (2-4) are often needed. The number is empirical and dictated by the signal-to-noise ratio of the biological response [34].

Guide 3: Preventing Sample Misidentification and Tracking Errors

Problem: Plates or samples are misidentified, leading to mixed-up data, lost tracks of specific plates, or misattributed results.

Explanation: In high-throughput environments, the sheer volume of plates processed increases the risk of human error, such as misreading handwritten labels or transposing data [35]. This is a pre-analytical error that can have severe consequences for data integrity.

Solution: Implement a robust, automated system for plate identification and tracking.

Step 1: Implement Barcode Labeling

- Label individual plates with barcodes that serve as a digital identifier, linking the plate to its experimental and sample data in your LIMS (Laboratory Information Management System) [35].

- For redundancy in automated workflows, apply barcodes to multiple sides of the microplate to ensure consistent identification regardless of orientation [35].

Step 2: Utilize Digital Well Plate Mapping

- Use a LIMS to digitally map individual wells, providing a comprehensive, interactive overview of the spatial arrangement of wells and associated experimental conditions [35].

Step 3: Establish Electronic Recordkeeping

- Replace paper notebooks and local spreadsheets with an Electronic Laboratory Notebook (ELN) or LIMS to centrally document experiment details, plate movements, and storage locations [35].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What defines an acceptable Z'-factor for a high-throughput screening (HTS) assay? While a Z'-factor > 0.5 is a traditional cutoff for most HTS assays, a value in the range of 0 to 0.5 is often acceptable for complex phenotypic HCS (High-Content Screening) assays. These assays may yield more subtle but still biologically valuable hits. Good judgment should prevail, factoring in the complexity of the screen and the tolerance for false positives that can be filtered out later [34].

Q2: How many replicates are typically used in an HTS screen? Most large HTS screens are performed in duplicate. Increasing replicates from 2 to 3 represents a 50% increase in reagent cost, which is often prohibitive for screens involving tens of thousands of samples. The standard practice is to screen in duplicate and then retest hits in more robust confirmation assays with higher replicate numbers [34].

Q3: Why are control wells not sufficient for ensuring plate quality? Control-based metrics like Z'-factor are fundamentally limited because they only assess a fraction of the plate's spatial area. They cannot detect systematic errors that specifically affect drug wells, such as:

- Compound-specific issues (e.g., drug precipitation, assay interference).

- Spatial artifacts (e.g., evaporation gradients, pipetting errors) in regions not covered by controls [10].

Q4: How does plate miniaturization impact reagent cost and data variability? Miniaturization (e.g., moving from 384-well to 1536-well formats) significantly reduces reagent costs by decreasing the required assay volume. However, it amplifies data variability because volumetric errors become magnified in smaller volumes. This necessitates the use of extremely high-precision dispensers and strict control over evaporation [33].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Quality Control Metrics for HTS Assay Validation

| Metric | Formula/Description | Interpretation | Acceptable Range for HTS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z'-factor [34] | 1 - [3(σ_p + σ_n) / |μ_p - μ_n|] |

Measures the separation band between positive (p) and negative (n) controls. Accounts for variability and dynamic range. | Ideal: >0.5, Acceptable for complex assays: 0 - 0.5 |

| Signal-to-Background (S/B) [33] | μ_p / μ_n |

The ratio of the mean signal of positive controls to the mean signal of negative controls. | >5 [10] |

| Strictly Standardized Mean Difference (SSMD) [10] | (μ_p - μ_n) / √(σ_p² + σ_n²) |

A robust measure for the difference between two groups that accounts for variability and is suitable for HTS. | >2 [10] |

| Normalized Residual Fit Error (NRFE) [10] | Based on deviations between observed and fitted dose-response values. | Detects systematic spatial artifacts in drug wells that are missed by control-based metrics. | Excellent: <10, Borderline: 10-15, Poor: >15 |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) [33] | (σ / μ) * 100 |

Measures the dispersion of data points in a sample around the mean, expressed as a percentage. | Should be minimized; specific threshold depends on assay. |

Table 2: Common Systematic Errors and Mitigation Strategies

| Error Type | Common Causes | Impact on Data | Prevention Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Edge Effects [34] | Uneven evaporation or heating from plate edges. | Over- or under-estimation of cellular responses in outer wells. | Use specialized plate sealants; humidified incubators; alternate control placement [34] [33]. |

| Liquid Handling Inaccuracies | Improperly calibrated or maintained dispensers. | Column/row-wise striping; high well-to-well variability. | Regular calibration; use of acoustic dispensers; verification with dye tests. |

| Plate Drift [33] | Reagent degradation, instrument warm-up, reader fatigue. | Signal window changes from the first to the last plate in a run. | Perform plate drift analysis during validation; use inter-plate controls. |

| Sample Mix-ups [35] | Human error in manual transcription; mislabeling. | Misattributed data; incorrect results linked to samples. | Implement barcode systems [35]; digital plate mapping [35]; two-person verification. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Plate Drift Analysis for Temporal Stability

Purpose: To confirm that an assay's signal window and statistical performance remain stable over the entire duration of a large screening campaign [33].

Methodology:

- Preparation: Prepare a sufficient number of identical control plates containing positive and negative controls in their designated wells.

- Run Simulation: Over a period that mimics a full screening run (e.g., 8-24 hours), run these control plates through the entire automated HTS workflow at regular intervals.

- Data Collection: For each plate, calculate key performance metrics, including Z'-factor, S/B, and mean values for positive and negative controls.

- Analysis: Plot each metric against the time the plate was run. Visually and statistically analyze the plots for any significant trends (e.g., a linear decline in Z'-factor).

Protocol 2: NRFE Calculation for Spatial Artifact Detection

Purpose: To quantitatively identify systematic spatial errors in drug-treated wells that are not detected by traditional control-based QC methods [10].

Methodology:

- Data Prerequisite: Obtain a plate with dose-response data for multiple compounds.

- Curve Fitting: Fit a dose-response model (e.g., a 4-parameter logistic curve) to the data for each compound on the plate.

- Residual Calculation: For each well, calculate the residual—the difference between the observed response and the fitted value from the curve.

- Normalization: Normalize the residuals to account for the variance structure of dose-response data, applying a binomial scaling factor.

- NRFE Computation: Calculate the NRFE for the plate. Plates with an NRFE > 15 should be flagged for careful review or exclusion.

- Implementation: This protocol is implemented in the publicly available

plateQCR package (https://github.com/IanevskiAleksandr/plateQC) [10].

Workflow Visualization

Systematic Error Detection Workflow

Integrated Quality Control Strategy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Strategic Assay Development |

|---|---|

| Barcoded Microplates [35] | Uniquely identifies each plate and links it to digital records, preventing misidentification and enabling seamless tracking through automated workflows. |

| Positive & Negative Controls [34] | Benchmarks for calculating assay quality metrics (e.g., Z'-factor). Should be selected to reflect the strength of expected hits, not just the strongest possible effect. |

| Electronic Laboratory Notebook (ELN)/LIMS [35] | Centralizes experimental data and metadata, enables digital well plate mapping, and ensures accurate, accessible, and complete electronic recordkeeping. |

| Plate Sealants & Humidified Incubators [33] | Mitigates edge effects by reducing evaporation gradients across the plate, a common source of spatial systematic error. |

| High-Precision Liquid Handlers | Ensures accurate and consistent dispensing of nanoliter volumes, critical for assay miniaturization and preventing systematic errors from pipetting inaccuracies. |

plateQC R Package [10] |

Provides a robust toolset for implementing the NRFE metric and other quality control analyses to detect spatial artifacts and improve data reliability. |

Leveraging Automation and Integrated Robotics for Reduced Human Variability

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the most common sources of human-induced variability in HTS, and how does automation address them? Human variability in HTS primarily arises from manual pipetting, inconsistencies in assay execution between users, and undocumented errors [4]. Automation addresses this through standardized robotic liquid handling, which ensures precise, sub-microliter dispensing identical across all wells and users [36] [37]. Integrated robotic systems also standardize incubation times and environmental conditions, eliminating these as sources of variation [36].

Our automated HTS runs are producing unexpected results. How do we determine if it's an assay or equipment issue? Begin by checking the quantitative metrics of your assay run. A sudden drop in the Z'-factor below 0.5 is a strong indicator of an assay quality or equipment performance issue [36] [38]. You should also:

- Inspect Control Values: Check if the mean values and coefficients of variation (CV) for your maximum and minimum control wells have deviated from established baselines. A high CV can point to liquid handling inconsistencies [38].

- Run a Diagnostic Test: Use the liquid handler's built-in verification features, if available. For example, technologies like DropDetection can verify that the correct volume was dispensed into each well [4].

- Check for Positional Effects: Create a heatmap of your readout signal across the microplate to identify patterns (like edge effects) that suggest environmental or washing inconsistencies [38].

We see patterns (e.g., row/column bias) in our HTS data heatmaps. What does this indicate? Positional effects, such as row or column biases, typically indicate technical issues related to the automated system rather than biological activity [38]. Common causes include:

- Liquid Handler Calibration: Improperly calibrated dispensers can lead to systematic volume errors across specific rows or columns.

- Plate Washer Performance: Inefficient washing can cause cross-contamination between adjacent wells.

- Incubator Conditions: A lack of uniform temperature or CO₂ across the plate can create gradients in cell-based assays. Investigate and service the specific module responsible for the pattern.

How can we ensure data integrity from our automated HTS platform for regulatory compliance? Robotics strengthen compliance by guaranteeing adherence to standardized procedures and robust reporting [39]. Implement a Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) to track all experimental metadata, including compound identity, plate location, and instrument parameters, creating a full audit trail [36]. Furthermore, ensure your automated systems and data software are compliant with electronic records standards like 21 CFR Part 11 [36].

Our HTS workflow integrates instruments from different vendors. How can we prevent bottlenecks and failures? Integration of legacy instrumentation is a common challenge, often requiring custom middleware or protocol converters [36]. To mitigate this:

- Use a Central Scheduler: Employ orchestration software (e.g., FlowPilot) to manage timing and sequencing across all instruments [28].

- Prioritize API-enabled Instruments: When acquiring new equipment, select devices with modern Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) for flexible software control and easier integration [40] [28].

- Design for Failure Recovery: Choose robotic components with features like automated fault recovery and self-cleaning to minimize downtime [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Rate of False Positives/Negatives in Screening Campaign

| Potential Cause | Investigation Method | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Assay robustness is low | Calculate the Z'-factor for each assay plate. A score below 0.5 indicates a poor separation band between your controls [36]. | Re-optimize the assay protocol before proceeding with full-scale screening. This may involve adjusting reagent concentrations, incubation times, or cell seeding density. |

| Liquid handling inaccuracy | Use a photometric or gravimetric method to verify the volume dispensed by the liquid handler across the entire plate. | Re-calibrate the liquid handling instrument. For critical low-volume steps, consider using a non-contact dispenser to eliminate errors from tip wetting and adhesion [4]. |

| Undetected positional effects | Generate a heatmap of the primary readout (e.g., fluorescence intensity) for each plate to visualize row, column, or edge effects [38]. | Investigate and address the root cause, which may involve servicing the plate washer, validating incubator uniformity, or adjusting the liquid handler's method to pre-wet tips. |

| Inconsistent cell health | Use an automated cell counter (e.g., Accuris QuadCount) to ensure consistent viability and seeding density at the start of the assay [37]. | Standardize cell culture and passage procedures. Implement automated cell seeding to improve reproducibility across all assay plates. |

Problem: Low Z'-Factor on an Automated HTS Run

| Potential Cause | Investigation Method | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in control wells | Check the Percent Coefficient of Variation (%CV) for both positive and maximum control wells. A CV >20% is a concern [38]. | Inspect the preparation of control solutions. Ensure the robotic method for dispensing controls is highly precise, potentially using a dedicated dispense step. |

| Poor signal-to-background (S/B) ratio | Calculate the S/B ratio. A ratio below a suitable threshold (e.g., 3:1) indicates a weak assay signal [38]. | Re-optimize assay detection parameters (e.g., gain, excitation/emission wavelengths) or consider using a more sensitive detection chemistry. |

| Instrument performance drift | Review the Z'-factor and control values by run date to identify a temporal trend, which may correlate with the last instrument service date [38]. | Perform full maintenance and calibration on the microplate reader and liquid handlers as per the manufacturer's schedule. |

Problem: Integration Failures in a Multi-Instrument Workcell

| Potential Cause | Investigation Method | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Communication failure between devices | Check the system scheduler log for error messages related to device time-outs or failed handshakes. | Verify physical connections and communication protocols (e.g., RS-232, Ethernet). Reset the connection and may require updating device drivers or the scheduler's communication middleware [36]. |

| Physical misalignment of robotic arm | Visually observe the robotic arm's movement during plate transfers to see if it accurately reaches deck positions. | Perform a re-homing sequence for the robotic arm and re-calibrate all deck positions according to the system's manual. |

| Inconsistent plate gripper operation | Run a diagnostic routine that tests the gripper's force and alignment. | Adjust the gripper force or replace worn gripper pads to ensure secure plate handling without jamming. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation and Troubleshooting

Protocol for Quantifying Assay Robustness (Z'-Factor Calculation)

Purpose: To quantitatively assess the quality and suitability of an assay for High-Throughput Screening by measuring the separation between positive and negative control populations [36] [38].

Materials:

- Assay reagents and cell line

- Positive control (known activator/inhibitor)

- Negative control (vehicle or buffer)

- Automated liquid handling system

- 384-well microplates

- Microplate reader

Methodology:

- Using the automated liquid handler, prepare at least 24 wells each of the positive control and negative control across multiple plates to capture inter-plate variability.

- Run the assay according to your standard protocol.

- On the microplate reader, measure the signal for all control wells.

- For each control population (positive and negative) on a plate, calculate:

- The mean of the signals (μpositive and μnegative)

- The standard deviation of the signals (σpositive and σnegative)

- Calculate the Z'-factor for the plate using the following equation [36]:

- Z' = 1 - [3(σpositive + σnegative) / |μpositive - μnegative|]

- Interpretation: A Z'-factor greater than 0.5 indicates an excellent assay robust enough for HTS. A Z'-factor between 0 and 0.5 may be usable but requires careful monitoring. A Z'-factor less than 0 indicates marginal or no separation between controls [36].

Protocol for Liquid Handler Performance Verification

Purpose: To validate the precision and accuracy of an automated liquid handling system, particularly for low-volume dispensing critical to miniaturized HTS [4] [37].

Materials:

- Automated liquid handler (e.g., I.DOT Non-Contact Dispenser, Accuris AutoMATE 96)

- A compatible, precise dye solution (e.g., tartrazine)

- UV-transparent 384-well microplate

- UV-Vis microplate reader

Methodology:

- Program the liquid handler to dispense the target volume (e.g., 1 µL) of the dye solution into every well of the microplate.

- Execute the dispense run.

- If the liquid handler is equipped with volume verification technology (e.g., DropDetection), review the log to confirm successful dispensing in all wells [4].

- Measure the absorbance of each well using the plate reader.

- Prepare a standard curve by dispensing and measuring known volumes/concentrations of the dye to correlate absorbance with volume.

- Analysis: Calculate the mean volume, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation (%CV) for all wells. A CV of less than 10% is generally acceptable, with lower values indicating higher precision. Compare the mean measured volume to the target volume to determine accuracy [37].

Table 1: Key Statistical Metrics for HTS Data Quality Assessment

| Metric | Calculation | Target Value | Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z'-Factor | 1 - [3(σp + σn) / | μp - μn | ] | > 0.5 | Measures assay robustness and separation between positive (p) and negative (n) controls [36]. |

| Signal-to-Background (S/B) | μp / μn | > 3 | Indicates the strength of the assay signal relative to the background noise [38]. | ||

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | (σ / μ) x 100 | < 20% | Measures the dispersion of data points in control wells; lower CV indicates higher precision [38]. | ||

| Signal-to-Noise (S/N) | (μp - μn) / √(σp² + σn²) | > 10 | Similar to S/B but incorporates variability; a higher value indicates a more reliable and detectable signal [38]. |

Table 2: Impact of Automation on Key HTS Parameters

| Parameter | Manual Process | Automated Process | Benefit of Automation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | ~100 samples/week [41] | >10,000 samples/day [41] | Dramatically accelerated screening timelines. |

| Liquid Handling Precision | High variability, especially at low volumes [4] | Sub-microliter accuracy with CV <10% [36] [37] | Improved data quality and reduced false positives/negatives. |

| Reproducibility | High inter- and intra-user variability [4] | Standardized workflows reduce variability [4] | Enables reproduction of results across users, sites, and time. |

| Operational Cost | High reagent consumption | Up to 90% reduction via miniaturization [4] | Significant cost savings per data point. |

Workflow and Process Diagrams

HTS Troubleshooting Logic

HTS System Validation Flow"

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Automated HTS

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| 384/1536-well Microplates | Miniaturized assay format that enables high-density screening and conserves expensive reagents [36]. | Standardized platform for all HTS assays. |

| Validated Control Compounds | Known active (positive) and inactive (negative) substances used to calibrate assays and calculate performance metrics like the Z'-factor [38]. | Assay validation and per-plate quality control. |

| Photometric Dye Solutions | Used in liquid handler performance verification to correlate absorbance with accurately dispensed volume [37]. | Periodic calibration of automated dispensers. |

| Cell Viability Assay Kits | Pre-optimized reagent kits (e.g., MTT, CellTiter-Glo) for measuring cell health and proliferation in automated cell-based screens. | Toxicity screening and normalization of cell-based data. |

| LIMS (Laboratory Information Management System) | Software platform that tracks all experimental metadata, ensures data integrity, and manages the audit trail for regulatory compliance [36]. | Centralized data management for all HTS projects. |

The Role of Advanced Liquid Handlers and Acoustic Dispensing in Precision

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

General Troubleshooting Guide

Q: My assay results show an unexpected pattern or trend. How do I determine if the liquid handler is the source? A: First, investigate if the pattern is repeatable. Run the test again to confirm the error is not a random event. A repeatable pattern often indicates a systematic liquid handling issue. Increasing the frequency of performance testing can help track the recurrence and pinpoint the root cause [42].

Q: What are the first steps I should take when I suspect a liquid handling error? A: Before assuming hardware failure, check the basics:

- Maintenance Schedule: Verify when the instrument was last serviced. Sedentary instruments are particularly prone to error [42].

- Liquid Class and Settings: Ensure the aspirate/dispense rates, heights, and liquid class settings are correctly defined for your specific reagent [43].