Transition Metal Catalysis vs. Biocatalysis: A Comparative Analysis of Efficiency and Application in Pharmaceutical Synthesis

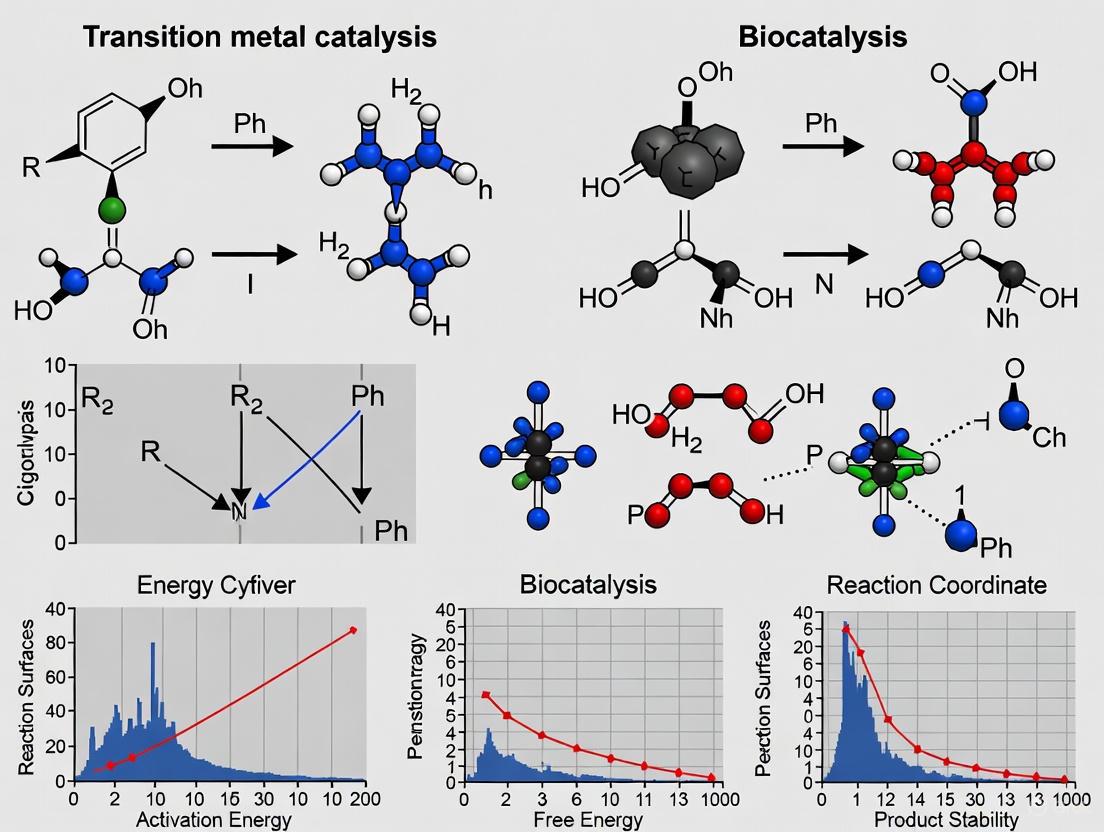

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of transition metal catalysis and biocatalysis, two pivotal technologies in modern pharmaceutical synthesis.

Transition Metal Catalysis vs. Biocatalysis: A Comparative Analysis of Efficiency and Application in Pharmaceutical Synthesis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of transition metal catalysis and biocatalysis, two pivotal technologies in modern pharmaceutical synthesis. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, distinct advantages, and inherent challenges of each approach. The scope ranges from fundamental mechanisms and key industrial applications to advanced optimization strategies and direct performance comparisons. By synthesizing the latest research, this review offers a practical framework for selecting and optimizing catalytic systems based on reaction requirements, substrate complexity, and process sustainability goals, ultimately guiding the development of more efficient and environmentally friendly synthetic routes for chiral drugs and complex intermediates.

Core Principles and Evolutionary Pathways in Catalysis

In the pursuit of efficient and sustainable synthetic methodologies, researchers and drug development professionals are often faced with a fundamental choice: transition metal complexes or enzymatic systems. Each catalytic platform offers distinct advantages and limitations, making the selection process critical for successful process development in pharmaceutical and fine chemical synthesis. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two catalytic approaches, examining their core mechanisms, efficiency metrics, and practical applications to inform strategic decision-making in research and development.

Transition metal complexes are typically discrete molecular structures where a metal ion is coordinated to organic ligands, enabling a wide range of transformations through versatile redox chemistry and orbital interactions [1] [2]. In contrast, enzymatic systems are protein-based biological catalysts that operate through precisely arranged active sites with complex three-dimensional structures, facilitating reactions through sophisticated binding pockets and dynamic motion [3]. Understanding the fundamental differences between these systems is essential for selecting the appropriate catalyst for a given application.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Operational Principles

How Transition Metal Complexes Operate

Transition metal catalysts function through their ability to access multiple oxidation states and coordinate substrates through available d-orbitals. The metal center acts as a template that brings reactants into close proximity and in the correct orientation, while simultaneously activating them toward reaction through electron transfer and orbital manipulation [2]. This versatility enables transformative reactions including cross-couplings (e.g., Suzuki, Heck), C-H activations, and metathesis reactions that often have no equivalent in biological systems [4].

Key advantages of transition metal complexes include:

- Broad functional group tolerance across diverse reaction conditions

- Compatibility with non-natural substrates not recognized by biological systems

- Tunable reactivity through ligand modification to fine-tune steric and electronic properties

- Operational simplicity in many organic solvents under controlled atmospheres

Notably, certain metal complexes have been engineered to function in biological environments. For instance, ruthenium complexes can catalyze uncaging reactions inside living cells, enabling controlled drug release through Alloc deprotection mechanisms [1]. This expanding capability demonstrates the growing sophistication of transition metal catalyst design.

How Enzymatic Systems Function

Enzymes achieve remarkable rate accelerations and specificities through a multi-factorial mechanism that extends beyond simple transition state stabilization. The conventional view of enzymes as rigid structural scaffolds that properly position substrates has been expanded to include the critical role of protein dynamics and conformational fluctuations [3].

The enzymatic catalytic cycle involves:

- Precise substrate binding in specialized active sites with complementary geometry

- Formation of transition state complexes stabilized through extensive non-covalent interactions

- Directed protein motions that facilitate the chemical transformation through promoting vibrations

- Product release and enzyme regeneration for subsequent catalytic cycles

Enzymes operate through networks of conserved residues that span from the protein surface to the active site. These networks serve as energy transfer pathways that enable thermodynamic coupling between the solvent environment and the catalytic center [3]. This sophisticated architecture allows enzymes to achieve extraordinary catalytic proficiencies, often accelerating reactions by more than 10^17-fold compared to uncatalyzed rates [3].

Quantitative Efficiency Comparison

Direct comparison of catalytic efficiency requires standardized metrics that account for multiple performance parameters. The Asymmetric Catalyst Efficiency (ACE) formula provides a valuable framework for quantitative assessment, defined as:

ACE = (Yield (%) × ee (%) × MW Product) / (Mol% catalyst × MW Catalyst × 10^4) [5]

This formula incorporates the critical factors of product yield, enantioselectivity, catalyst loading, and molecular economy into a single comparable value.

Table 1: Efficiency Comparison of Representative Catalytic Systems

| Catalyst Type | Reaction | Yield (%) | ee (%) | Catalyst Loading (mol%) | ACE Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ru Complex (Hydrogenation) | Asymmetric hydrogenation | 99.6 | 79 | 0.00044 | 76,096 |

| Pd Complex (Cross-coupling) | Suzuki-Miyaura | 98 | 95 | 1.0 | 42.7 |

| Organocatalyst (Aldol) | Proline-catalyzed aldol | 86 | 84 | 48.0 | 2.33 |

| Antibody Catalyst | Intramolecular aldol | 94 | 95 | 0.114 | 0.93 |

| Hydrolase Enzyme | Hydrolytic desymmetrisation | 86 | 95 | 0.00068 | 267 |

Table 2: Performance Characteristics Across Catalyst Classes

| Parameter | Transition Metal Complexes | Enzymatic Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Turnover Frequencies | Variable: 1-500 h⁻¹ (molecular) | Often extremely high: up to 758,823 h⁻¹ reported [5] |

| Functional Group Tolerance | Broad | Can be limited for non-natural substrates |

| Solvent Compatibility | Organic solvents predominant | Aqueous buffers preferred |

| Temperature Range | Often elevated temperatures | Moderate temperatures (20-40°C) |

| Operational Stability | Can be sensitive to air/moisture | Variable; can be fragile |

| Tunability | High through ligand design | Moderate via protein engineering |

The data reveals that both catalyst classes can achieve outstanding efficiency, with the highest ACE values observed for specialized transition metal complexes in hydrogenation reactions and engineered enzymes in hydrolytic desymmetrisation [5]. The molecular economy of metal complexes (lower molecular weight) often provides an advantage in ACE calculations, though enzymes achieve remarkable efficiency through extremely low catalyst loadings.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Transition Metal Catalysis in Biological Environments

The application of transition metal catalysts in cellular environments requires specialized protocols to address unique biological constraints:

Catalyst Design Considerations:

- Complex Stability: Design metal complexes resistant to demetallation by biological nucleophiles (glutathione, amines) [1]

- Membrane Permeability: Incorporate structural features that enable cellular uptake while maintaining catalytic activity

- Aqueous Compatibility: Ensure solubility and stability in complex aqueous media with high salt concentrations

- Low Toxicity Profile: Minimize cytotoxic effects through metal selection and ligand design

Experimental Procedure for Intracellular Catalysis:

- Catalyst Preparation: Synthesize and characterize biocompatible metal complex (e.g., Ru(IV) allyl complex)

- Cell Culture Preparation: Grow mammalian cells (e.g., HeLa cells) to appropriate confluence in culture media

- Incubation with Catalyst: Add metal catalyst (typically 10-50 μM) and caged substrate to cell culture

- Reaction Monitoring: Measure fluorescence increase or product formation over time (minutes to hours)

- Viability Assessment: Conduct cytotoxicity assays (MTT, Live/Dead) to confirm minimal toxicity

- Localization Studies: Use confocal microscopy to verify intracellular reaction sites [1]

Critical Controls:

- Test substrate and catalyst separately to establish baseline effects

- Include thiol additives (e.g., thiophenol) when required for catalytic activity

- Verify membrane diffusion through staining experiments

Protocol for Chemoenzymatic Cascade Reactions

Integrating enzymatic and transition metal catalysis enables sequential transformations without intermediate isolation:

System Design Considerations:

- Reaction Compatibility: Ensure enzymatic and metal-catalyzed steps operate under compatible conditions

- Temporal Control: Sequence reactions to prevent catalyst interference or deactivation

- Medium Optimization: Balance aqueous requirements of enzymes with solvent preferences of metal complexes

Experimental Procedure for One-Pot Cascade:

- Biocatalytic Step Setup: Combine substrate, enzyme, and cofactors in appropriate buffer

- Initial Reaction: Monitor first transformation to near-completion (analytical methods: TLC, HPLC)

- Metal Catalyst Introduction: Add transition metal complex and additional ligands if required

- Condition Adjustment: Modify temperature, pH, or solvent composition as needed

- Reaction Monitoring: Track both transformations simultaneously or sequentially

- Product Isolation: Purify final product and determine yield and selectivity [6]

Compatibility Strategies:

- Use compartmentalization approaches (e.g., enzyme immobilization)

- Employ gradual condition modification between steps

- Implement spatial separation through supported catalysts

Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting appropriate reagents and materials is essential for successful implementation of either catalytic approach.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Catalytic Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Catalysts | [Cp*Ru(cod)Cl], Ru(IV) allyl complexes, Pd(PPh₃)₄ | Core catalytic entities for diverse transformations |

| Enzymatic Preparations | Alcohol dehydrogenases, hydrolases, transaminases | Biological catalysts for selective transformations |

| Ligands/Co-factors | Phosphines, N-heterocyclic carbenes, NAD(P)H, ATP | Modify metal catalyst properties or serve as enzyme cofactors |

| Specialized Substrates | Caged fluorophores (e.g., Alloc-rhodamine), pro-drugs | Enable reaction monitoring and biological applications |

| Compatibility Additives | Thiol sources (glutathione, thiophenol), sacrificial reagents | Maintain catalyst activity in challenging environments |

| Analytical Tools | Chiral HPLC columns, LC-MS systems, fluorescence detectors | Determine yield, selectivity, and reaction progress |

Applications in Drug Development and Synthesis

Transition Metal Complexes in Pharmaceutical Applications

Transition metal catalysts have enabled critical advancements in pharmaceutical synthesis through their versatility in forming key chemical bonds:

Case Study: Dragmacidin D Synthesis The complex marine alkaloid Dragmacidin D, a potent inhibitor of serine-threonine protein phosphatases with significant cytotoxicity against cancer cell lines, was efficiently synthesized using sequential Pd-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reactions as key steps [4]. This demonstrates the power of transition metal catalysis in constructing complex natural product scaffolds with pharmaceutical relevance.

Prodrug Activation Strategies Ruthenium complexes have been employed for intracellular prodrug activation through catalytic uncaging reactions. For example, a Ru(IV) catalyst successfully activated an N-Alloc protected doxorubicin prodrug inside HeLa cells, dramatically reducing cell viability (to 2-7%) compared to minimal effects from prodrug or catalyst alone [1]. This approach demonstrates the therapeutic potential of transition metal catalysis in biological environments.

Enzymatic Systems in Pharmaceutical Synthesis

Enzymes provide unparalleled selectivity in the synthesis of chiral pharmaceutical intermediates:

Stereoselective Transformations Enzymes such as alcohol dehydrogenases and hydrolases achieve exceptional stereocontrol in the synthesis of chiral building blocks. For instance, Thermoanaerobacter brockii alcohol dehydrogenase catalyzes the reduction of ketones with high enantioselectivity (99% ee), enabling production of enantiopure pharmaceutical intermediates [5].

Chemoenzymatic Cascades The integration of enzymatic and transition metal catalysis enables efficient multi-step synthesis. Recent advances include combining Pd catalysts with enzymes for dynamic kinetic resolutions and tandem processes, minimizing purification steps and improving overall efficiency in API synthesis [6].

Strategic Selection Guide

The choice between transition metal complexes and enzymatic systems depends on multiple application-specific factors, which can be visualized through the following decision pathway:

Catalyst Selection Decision Pathway

This decision pathway provides a systematic approach for selecting the optimal catalytic system based on substrate characteristics, selectivity requirements, and process conditions. Hybrid chemoenzymatic approaches often provide optimal solutions when a single catalyst class cannot address all requirements [6].

Transition metal complexes and enzymatic systems represent complementary rather than competing catalytic platforms. Transition metal complexes offer exceptional versatility across diverse substrates and reaction types, with growing capabilities in biological environments. Enzymatic systems provide unparalleled selectivity and efficiency for natural substrates and their analogs under mild conditions. The emerging field of hybrid chemoenzymatic catalysis leverages the strengths of both approaches, enabling sophisticated multi-step transformations that overcome the limitations of either system alone [6].

Future developments will likely focus on increasing the compatibility of these systems through engineering efforts—designing more robust enzymes for non-natural environments and developing increasingly sophisticated metal complexes for biological applications. This convergence of biological and synthetic catalysis represents a promising frontier for pharmaceutical synthesis and therapeutic development.

Historical Development and Industrial Adoption Trajectories

This guide provides an objective comparison between transition metal catalysis and biocatalysis, two pivotal methodologies in modern chemical synthesis, with a particular focus on pharmaceutical and fine chemical manufacturing. The analysis is structured to aid researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in making informed decisions based on historical context, performance data, and practical experimental considerations.

Historical Development and Industrial Adoption

The trajectories of transition metal catalysis and biocatalysis have been shaped by distinct scientific breakthroughs and industrial needs.

Transition metal catalysis gained prominence with the development of cross-coupling reactions, recognized by the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2010 for palladium-catalyzed reactions such as Suzuki-Miyaura, Negishi, and Heck couplings [4]. These methods provided unprecedented tools for forming carbon-carbon bonds, revolutionizing the synthesis of complex organic molecules, including marine drugs and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) [4]. The field is now advancing through integration with nanomaterials to enhance biocompatibility and targeting for biomedical applications like bioorthogonal catalysis in tumor therapy [7].

Biocatalysis leverages enzymes for organic transformations, with industrial roots dating back nearly a century. Early examples include:

- 1920s: Use of Acetobacter suboxydans for the regio- and chemoselective oxidation of d-sorbose in vitamin C synthesis, a process still used industrially [8].

- 1921: A stereoselective benzoin reaction using baker's yeast as a key step in the industrial synthesis of (−)-ephedrine [8].

- Modern Era: The industrial-scale production of acrylamide via enzymatic hydration of acrylonitrile, showcasing high chemoselectivity and ease of catalyst separation [8].

The following table summarizes the key developmental milestones:

Table 1: Historical Development and Industrial Adoption Milestones

| Era | Transition Metal Catalysis | Biocatalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-2000 | Development of fundamental cross-coupling reactions (e.g., Suzuki, Heck) [4]. | Early industrial processes using whole cells (e.g., Vitamin C, Ephedrine) [8]. |

| 2000-2010 | Nobel Prize (2010) for Pd-catalyzed cross-couplings; expansion into complex molecule synthesis [4]. | Shift towards using defined enzymes; protein engineering begins to expand enzyme toolbox [8]. |

| 2010-Present | Emergence of bioorthogonal catalysis for biomedical applications; integration with nanomaterials [7]. | Widespread adoption in pharmaceutical synthesis; focus on sustainability, engineering, and non-natural reactions [9] [8]. |

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The selection between transition metal catalysis and biocatalysis often hinges on performance metrics such as selectivity, sustainability, and functional group tolerance.

Comparative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Transition Metal Catalysis vs. Biocatalysis

| Performance Metric | Transition Metal Catalysis | Biocatalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Group Tolerance | Broad tolerance, tunable via metal/ligand choice [4]. | Can be exquisite, but may be narrow for wild-type enzymes; engineering can expand scope [8]. |

| Stereoselectivity | Achieved with chiral ligands, can be high [4]. | Typically innate and high due to precise positioning in enzyme active site [8]. |

| Regioselectivity | Moderate to high, depending on catalyst and substrate. | Often exceptionally high (e.g., specific C-H oxidations in complex molecules) [8]. |

| Reaction Scope | Very broad, including C-H activation, cross-coupling, metathesis [4]. | Broad and expanding via engineering; access to abiological reactions [9]. |

| Sustainability | Can generate HX waste from cross-couplings; some metals are scarce/expensive [4]. | High; catalysts are derived from renewable resources, biodegradable, and operate in mild conditions [8]. |

| Typical Operating Conditions | Often requires inert atmosphere, elevated temperatures. | Ambient temperature and pressure; aqueous buffers [8]. |

Experimental Data from Key Applications

Transition Metal Catalysis in Drug Synthesis:

- Application: Total synthesis of the marine alkaloid Dragmacidin D, a potent cytotoxin [4].

- Reaction: Sequential Pd-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reactions were the key steps in constructing the complex bisindole scaffold [4].

- Performance: This methodology enabled the efficient formation of critical C-C bonds that would be challenging to achieve using traditional synthetic methods.

Biocatalysis in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing:

- Application: Synthesis of (R)-phenylacetyl carbinol ((R)-PAC), a key intermediate for (−)-ephedrine [8].

- Reaction: Stereoselective benzoin condensation catalyzed by enzymes in baker's yeast.

- Performance: The biocatalytic reaction forms a new C-C bond with high stereoselectivity, providing a direct and efficient route to the chiral precursor [8].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

This is a general protocol for biaryl synthesis, as used in marine drug synthesis.

- Reaction Setup: In an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen or argon) glove box or using Schlenk techniques, charge a flame-dried reaction vessel with the organohalide substrate (e.g., 1.0 equiv), arylboronic acid/ester (1.2-1.5 equiv), and a base (e.g., K₂CO₃, Cs₂CO₃; 2.0-3.0 equiv).

- Catalyst Introduction: Add the palladium catalyst (e.g., Pd(PPh₃)₄, Pd(dba)₂; 1-5 mol%) and a suitable ligand if required.

- Solvent Addition: Introduce a degassed solvent (e.g., toluene/ethanol mixture, dioxane, DMF) via syringe.

- Reaction Execution: Seal the vessel, remove it from the glove box if used, and heat the reaction mixture to the required temperature (e.g., 80-100 °C) with stirring for the determined time (e.g., 4-16 hours), monitoring by TLC or LC-MS.

- Work-up: Cool the reaction mixture to room temperature. Dilute with water and an organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate). Separate the organic layer and wash with brine, dry over anhydrous MgSO₄ or Na₂SO₄, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Purification: Purify the crude product by flash chromatography on silica gel to obtain the desired biaryl product.

This protocol is adapted from industrial regio- and chemoselective oxidations.

- Enzyme Preparation: Obtain a crude cell extract or a purified enzyme preparation containing the desired oxidase (e.g., alcohol dehydrogenase) in a suitable buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 7.0-8.0).

- Cofactor Addition: If the enzyme is cofactor-dependent (e.g., NAD⁺/NADH), add the required cofactor (e.g., 0.1-1.0 mM) to the reaction mixture. For oxidases, molecular oxygen often serves as the final electron acceptor.

- Substrate Addition: Add the substrate (e.g., a sec-alcohol) to the buffered enzyme solution. The substrate may be dissolved in a water-miscible cosolvent (e.g., DMSO, <5% v/v) to ensure solubility.

- Reaction Execution: Incubate the reaction mixture at a controlled temperature (e.g., 25-37 °C) with gentle shaking or stirring for the required duration (e.g., 2-24 hours).

- Reaction Monitoring: Monitor reaction progress by analyzing aliquots via HPLC, GC, or TLC.

- Work-up and Extraction: Terminate the reaction by adding a water-immiscible organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate, dichloromethane). Separate the organic layer, dry over anhydrous Na₂SO₄, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Purification: Purify the product if necessary using standard techniques like chromatography or crystallization.

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Catalyst Selection and Application Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting and applying these catalytic methods in a research or development setting.

Diagram 1: Catalyst Selection Workflow

Mechanism of Bioorthogonal Catalysis with Nanomaterials

This diagram outlines the mechanism by which transition metals, when integrated with nanomaterials, enable bioorthogonal catalysis for biomedical applications like targeted drug activation [7].

Diagram 2: Bioorthogonal Drug Activation Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This section details essential reagents, materials, and tools used in experimental work for both transition metal catalysis and biocatalysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name | Function/Application | Relevant Field |

|---|---|---|

| Palladium Catalysts (e.g., Pd(PPh₃)₄, Pd(dba)₂) | Catalyze key C-C bond formation reactions like Suzuki-Miyaura cross-couplings [4]. | Transition Metal Catalysis |

| Chiral Ligands (e.g., BINAP, Salen ligands) | Impart stereocontrol in asymmetric metal-catalyzed reactions like hydrogenations [4]. | Transition Metal Catalysis |

| Organometallic Reagents (e.g., Arylboronic acids, organozincs) | Act as coupling partners in cross-coupling reactions with organic halides [4]. | Transition Metal Catalysis |

| Nanomaterial Supports (e.g., Polymers, Metal-Organic Frameworks) | Enhance biocompatibility, stability, and targeting of transition metal catalysts for bioorthogonal applications [7]. | Transition Metal Catalysis |

| Defined Enzyme Preparations | Crude extracts or purified enzymes used as selective catalysts for specific transformations (e.g., ketoreductases) [8]. | Biocatalysis |

| Cofactors (e.g., NAD(P)H, NAD(P)⁺) | Essential for the activity of many oxidoreductase enzymes; often used in recycling systems [8]. | Biocatalysis |

| Engineered Whole Cells (e.g., E. coli, P. pastoris) | Used as hosts for heterologous enzyme production or as self-regenerating catalytic systems [8]. | Biocatalysis |

| Protein Engineering Kits | Enable directed evolution (e.g., error-prone PCR) to improve enzyme stability, activity, or selectivity [9] [10]. | Biocatalysis |

Both transition metal catalysis and biocatalysis are powerful, mature technologies with distinct strengths. Transition metal catalysis offers a exceptionally broad reaction scope and tunability, making it indispensable for constructing complex scaffolds in discovery chemistry and API synthesis. Biocatalysis excels in sustainability and often provides unmatched selectivity under mild conditions, driving its rapid adoption in green manufacturing processes, especially for chiral synthons.

The future lies not in choosing one over the other, but in their strategic integration. Emerging fields like artificial metalloenzymes, which incorporate transition metal catalysts into protein scaffolds, aim to merge the broad reactivity of metals with the precise control of enzymes [10]. Furthermore, the application of transition metals in bioorthogonal catalysis, facilitated by nanomaterials, opens new frontiers for targeted therapeutic activation directly within complex biological systems [7]. For researchers, the optimal path forward involves a synergistic approach, selecting the best tool—or combination thereof—for the specific synthetic challenge at hand.

Transition metal catalysis is a cornerstone of modern synthetic chemistry, enabling the efficient construction of chemical bonds for pharmaceutical and fine chemical synthesis. A fundamental dichotomy in these processes is the competition between two-electron and radical one-electron pathways [11]. Two-electron processes involve concerted movements of electron pairs and are characteristic of precious metals like Pd, Pt, and Ir, following classical organometallic mechanisms such as oxidative addition and reductive elimination. In contrast, radical one-electron pathways are more prevalent with earth-abundant first-row transition metals (Fe, Co, Ni, Cu) and involve neutral, electron-deficient species with unpaired electrons [12] [13].

Understanding this mechanistic divide is crucial for catalyst design, particularly in the broader context of comparing transition metal catalysis with biocatalysis. While enzymatic catalysis often exploits radical mechanisms with exquisite precision, synthetic chemists are now harnessing these once-avoided pathways to achieve transformations inaccessible through traditional two-electron chemistry.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Governing Principles

Two-Electron Pathways: The Precious Metal Paradigm

Two-electron processes form the foundation of traditional homogeneous catalysis. The catalytic cycle typically involves three key steps: 1) oxidative addition, where a substrate adds to the metal center with simultaneous metal oxidation; 2) transmetalation or substrate modification; and 3) reductive elimination, where the product forms with reduction of the metal center [11]. These cycles are most efficiently mediated by late second- and third-row transition metals (e.g., Pd, Pt) supported by strong-field ligands like phosphines or N-heterocyclic carbenes that favor low-spin configurations [11].

The stability of these catalysts stems from their diffuse d-orbitals, which facilitate strong metal-ligand bonding and stabilize intermediates across a range of oxidation states. This predictable behavior enables precise control in pharmaceutical synthesis, where specific regio- and stereochemistry is often required.

Radical One-Electron Pathways: The First-Row Metal Signature

First-row transition metals (Fe, Co, Ni, Cu) exhibit a greater tendency toward one-electron redox processes due to their more compact 3d orbitals and resulting weaker ligand field effects [13]. This often leads to the formation of radical intermediates, which can be either a challenge for controlling selectivity or an opportunity for accessing unique reactivity.

Radical stability follows predictable trends: tertiary > secondary > primary > methyl radicals, with significant stabilization through resonance delocalization and adjacent atoms with lone pairs (e.g., O, N) [12]. The geometry of carbon-centered radicals is typically a "shallow pyramid" that can flatten to sp² hybridization when adjacent to π systems, enabling delocalization [12].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Radical vs. Two-Electron Pathways

| Feature | Radical Pathways | Two-Electron Pathways |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Metals | Fe, Co, Ni, Cu | Pd, Pt, Rh, Ir |

| Electron Count | One-electron steps | Two-electron steps |

| Key Intermediates | Radical species | Oxidized/reduced metal complexes |

| Ligand Preference | Weak-field ligands | Strong-field ligands |

| Typical Selectivity | Often governed by radical stability | Often governed by sterics/electronics at metal center |

| Common in Biology | Yes (e.g., radical SAM enzymes) | Less common |

Direct Comparative Studies: Experimental Evidence

Gas-Phase Studies of Model Complexes

Recent gas-phase studies of late 3d-metal complexes [(Me₃SiCH₂)ₙM]⁻ (M = Fe, Co, Ni, Cu; n = 2–4) provide direct insight into the intrinsic competition between one- and two-electron pathways [13]. Using tandem mass spectrometry coupled with quantum-chemical computations, researchers found that one-electron reactions (homolytic bond cleavages, radical dissociations) are typically entropically favored across all metals studied.

However, the preference between pathways shows a clear trend across the period: for [R₄Fe]⁻ and [R₄Co]⁻, one-electron fragmentations are both energetically and entropically preferred. In contrast, for [R₄Ni]⁻ and especially [R₄Cu]⁻, the concerted reductive elimination (a two-electron process) becomes increasingly energetically favorable [13].

Table 2: Metal-Dependent Pathway Preference in [R₄M]⁻ Complexes

| Metal | Electronic Configuration | Preferred Pathway | Key Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe | d⁵ (intermediate spin S=3/2) | One-electron | Radical dissociations energetically favored |

| Co | d⁶ (intermediate spin S=1) | One-electron | Similar to Fe but with smaller energy gap |

| Ni | d⁷ (low spin S=1/2) | Competitive | Nearly degenerate spin states |

| Cu | d⁸ (low spin S=0) | Two-electron | Reductive elimination energetically favored |

This systematic analysis reveals that the relative order of the first and second bond-dissociation energies is a key factor controlling the competition between radical dissociations and concerted reductive eliminations [13].

Ligand Field Control of Pathway Selection

The electronic structure of metal complexes, primarily controlled through ligand design, dramatically influences pathway selection. Strong ligand fields can promote low-spin electron configurations in first-row metals, enabling two-electron redox chemistry [11]. For example, iron complexes supported by strong-field ligands like dmpe (1,2-bis(dimethylphosphino)ethane) can undergo stoichiometric oxidative addition of C-H bonds, a classical two-electron process [11].

The strategic use of redox-active ligands provides another approach, where the ligand participates in electron transfer events, effectively enabling net two-electron transformations at metal centers that would typically prefer one-electron chemistry [11]. This electronic metal-ligand cooperativity represents a sophisticated biomimetic strategy, analogous to how enzymes use prosthetic groups to modulate metallocofactor reactivity.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Techniques for Mechanistic Discrimination

Discriminating between radical and two-electron pathways requires multiple complementary techniques:

- Gas-phase mass spectrometry combined with statistical rate-theory calculations provides pathway-specific energetic and entropic parameters free from solvent and counterion effects [13]

- Radical clock experiments using substrates that undergo rapid, diagnostic rearrangement upon radical formation can trap radical intermediates

- Kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) differ significantly between concerted metal insertion (typically small KIEs) and hydrogen atom transfer (often large KIEs)

- Stern-Volmer quenching studies and radical scavenger experiments can probe for radical chain processes

- Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy directly detects paramagnetic intermediates

Case Study: Photocatalytic C-H Arylation

A illustrative example of pathway control comes from photocatalytic C-H arylation. Traditional Pd-catalyzed arylation with diaryliodonium salts follows a two-electron "ionic" pathway requiring high temperatures (80-110°C) [14]. In contrast, introducing a photocatalyst (e.g., Ir(ppy)₂(dtbbpy)PF₆) under visible light irradiation enables a radical mechanism that proceeds efficiently at room temperature [14].

Critical evidence for the radical pathway includes:

- Complete inhibition by radical scavengers

- Absolute requirement for light irradiation

- Dramatically different chemoselectivity patterns compared to the thermal reaction

- Compatibility with directing groups that fail under thermal conditions [14]

This radical mechanism enables complementary substrate scope and functional group tolerance compared to the traditional two-electron pathway.

Diagram 1: Contrasting radical and two-electron pathways in C-H arylation. The radical pathway enabled by photocatalysis proceeds under milder conditions (25°C) compared to the traditional two-electron pathway (100°C).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Catalytic Pathways

| Reagent/Catalyst | Function | Mechanistic Role |

|---|---|---|

| [(Me₃SiCH₂)ₙM]⁻ complexes | Model systems for gas-phase studies | Intrinsic metal reactivity without solvent effects [13] |

| Ir(ppy)₂(dtbbpy)PF₆ | Photoredox catalyst | Generates radicals under mild conditions [14] |

| Diaryliodonium salts | Aryl radical precursors | Source of aryl radicals in photocatalytic C-H arylation [14] |

| Dimethylphosphinoethane (dmpe) | Strong-field ligand | Promotes two-electron pathways in Fe complexes [11] |

| TEMPO (2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl | Radical scavenger | Mechanistic probe for radical intermediates [14] |

| HBPin (Pinacolborane) | Borylation reagent | Substrate for radical borylation catalysis [11] |

Implications for Catalyst Design and Selection

The choice between radical and two-electron pathways has profound practical implications:

- Earth-abundant metal catalysis often leverages radical pathways for unique bond formations inaccessible to precious metals [11]

- Pharmaceutical synthesis may prefer two-electron pathways for predictable stereochemical outcomes, though radical approaches offer complementary reactivity

- Sustainability considerations favor iron and cobalt catalysts, but pathway control requires sophisticated ligand design

- Biocatalysis relevance: Enzymes proficiently control radical pathways through precise secondary coordination sphere effects—a key inspiration for next-generation catalyst design

The strategic selection between these mechanistic paradigms enables synthetic chemists to access complementary chemical space, much like biological systems employ both polar and radical mechanisms in metabolic pathways.

Diagram 2: Strategic decision-making for pathway selection in catalyst design, highlighting key criteria including metal identity, ligand properties, and reaction conditions.

Biocatalysis, the use of natural catalysts like enzymes to perform chemical transformations, has become an indispensable tool in modern organic synthesis, particularly within the pharmaceutical industry [15] [16]. This shift is driven by the need for more sustainable and efficient manufacturing processes that align with green chemistry principles [17]. Enzymes, as biological catalysts, offer remarkable specificity and the ability to function under mild reaction conditions, reducing the environmental footprint of chemical production [18]. The expansion of the biocatalysis toolbox has been fueled by advanced tools for enzyme discovery and high-throughput laboratory evolution techniques, enabling the rapid production of tailor-made enzymes with high efficiencies and selectivities on industrially relevant scales [15]. This guide objectively compares the performance of biocatalysis against traditional transition metal catalysis, providing supporting experimental data and methodologies to illustrate the distinct advantages enzyme-based approaches offer to researchers and drug development professionals.

The Inherent Advantages of Biocatalysis

Biocatalysis presents several compelling benefits over traditional chemocatalysis, rooted in the fundamental properties of enzymes.

- Exceptional Specificity: Enzymes are large, three-dimensional structures that make multiple contact points with a substrate, enabling exquisite stereo-, regio-, and chemo-selectivity [19]. This precision often eliminates the need for protection and deprotection steps, streamlining synthetic routes [19].

- Green and Sustainable Profile: Enzymes are produced from inexpensive renewable resources and are biodegradable [19]. They operate under mild conditions (ambient temperature and pressure), significantly reducing energy consumption and avoiding the use of precious metals, whose scarcity and mining carry environmental and supply chain concerns [17] [19].

- Economic Efficiency: The combination of high yields, reduced steps, lower energy requirements, and minimized waste disposal leads to a lower total cost for many industrial processes [18]. The stability and predictability of enzyme production costs also offer an advantage over the price volatility of precious metals like rhodium [19].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Biocatalysis vs. Transition Metal Catalysis

| Criterion | Biocatalysis | Traditional Chemical Catalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Specificity | High specificity ensures precise reactions, leading to fewer by-products [19] [18]. | Often lacks specificity, leading to more by-products and requiring further purification [18]. |

| Energy Requirements | Operates under mild conditions (e.g., ambient temperature/pressure), resulting in lower energy consumption [17] [18]. | Often requires high energy input (e.g., high temperature/pressure), leading to increased operational costs [17] [18]. |

| Environmental Impact | Minimal use of hazardous chemicals; catalysts are biodegradable from renewable resources [19] [18]. | Frequently utilizes harsh chemicals and solvents, resulting in more significant environmental pollution and disposal challenges [18]. |

| Operational Costs | Lower due to reduced energy needs, minimal waste generation, and fewer purification steps [17] [18]. | Higher due to increased energy consumption, waste management, and complex purification processes [18]. |

| Safety | Safer processes due to the absence of harsh chemicals and extreme conditions [18]. | Potential safety risks associated with handling hazardous chemicals and operation under extreme conditions [18]. |

Key Enzyme Classes and Their Industrial Applications

The biocatalytic toolbox has expanded dramatically, with several enzyme classes now routinely employed for key synthetic transformations.

Table 2: Key Enzyme Classes, Native Functions, and Industrial Applications

| Enzyme Class | Native Function (EC Number) | Key Industrial Application & Example | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transaminases | Transfer of an amino group from an amino donor to a keto acceptor (EC 2.6.1.-) [19]. | Synthesis of chiral amines: Production of the diabetes drug Sitagliptin via an engineered transaminase, replacing a high-pressure rhodium-catalyzed hydrogenation [17] [19]. | The engineered transaminase process achieved a higher overall yield, eliminated the use of a toxic metal, and ran under ambient pressure [17]. |

| Ketoreductases (KREDs) | Reduction of ketones to secondary alcohols (EC 1.1.1.-) [17] [19]. | Enantiospecific synthesis of secondary alcohols: Production of stereodefined alcohols as key intermediates for APIs like atorvastatin [17]. | KREDs are often used with cofactor recycling systems (e.g., glucose/glucose dehydrogenase) for economical, large-scale application [19]. |

| Nitrilases / Nitrile Hydratases | Hydrolysis of nitriles to carboxylic acids or amides (EC 3.5.5.1 / EC 4.2.1.84) [15]. | Industrial production of acrylamide: Nitrile hydratase is used for the large-scale synthesis of acrylamide from acrylonitrile [15]. | The enzymatic process is highly efficient and selective, operating on a multi-ton scale [15]. |

| Oxidases (e.g., P450s) | Oxidation of C-H and other bonds (EC 1.14.-.-) [15] [16]. | Steroid hydroxylation: Regioselective hydroxylation of steroids for cortisone production. C–H oxyfunctionalization of complex molecules [15] [20] [16]. | Engineered P450 enzymes have been applied to the oxidative degradation of volatile methyl siloxanes, persistent pollutants [16]. |

| Imine Reductases (IREDs) | Reduction of imines to amines (EC 1.5.-.-) [17]. | Reductive amination: Convergent synthesis of secondary and tertiary chiral amine drug targets, such as an intermediate for the JAK1 inhibitor abrocitinib [16]. | IREDs enable direct asymmetric reductive amination of ketones and amines, streamlining synthetic routes [16] [17]. |

Enzyme Functions and Engineering

Experimental Data & Case Studies: Direct Performance Comparison

Case Study: The Sitagliptin Synthesis

Objective: To develop a safer, more efficient, and economical process for manufacturing the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) of Sitagliptin (Januvia) [17] [19].

Methodology:

- Traditional Chemocatalytic Route: An asymmetric hydrogenation of an enamine using a rhodium/Josiphos catalyst at high pressure and temperature [17].

- Biocatalytic Route: A transaminase enzyme was engineered via directed evolution to catalyze the conversion of a pro-sitagliptin ketone directly to the chiral amine (S)-sitagliptin [17] [19].

Table 3: Experimental Data Comparison for Sitagliptin Synthesis

| Parameter | Rh/Josiphos Catalysis | Engineered Transaminase |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst | Rhodium metal complex | Engineered transaminase enzyme |

| Reaction Conditions | High-pressure H₂, elevated temperature | Ambient pressure, near-ambient temperature |

| Catalyst Safety | Toxic heavy metal requiring removal | Biodegradable, no heavy metal waste |

| Overall Yield | Lower | Higher |

| Product Purity | Required purification | High purity, meeting API standards |

| Environmental Factor (E-Factor) | Higher (more waste) | Lower (less waste) |

Conclusion: The biocatalytic process met green chemistry principles by improving atom economy, waste prevention, and energy efficiency, while also delivering economic benefits [17].

Case Study: Hybrid Chemo-Enzymatic Catalysis in a Micellar Environment

Objective: To bridge the gap between transition metal and bio-catalysis by performing sequential reactions in one pot, which is often hindered by catalyst incompatibility [21].

Methodology:

- Reaction Design: A transition metal-catalyzed reaction (e.g., Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling) was performed first in an aqueous solution of the designer surfactant TPGS-750-M, which forms nanomicelles. This was followed, in the same pot, by an enzymatic reduction using an alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) [21].

- Key Experimental Variable: The reduction of a ketone-containing product from a Heck coupling (2-ethylhexyl (E)-3-(4-acetylphenyl)acrylate) was monitored over time in buffer alone versus in 2 wt% TPGS-750-M/buffer [21].

Results: The conversion plateaued at 30% in pure buffer but reached over 90% in the micellar system [21]. The micelles acted as a reservoir for substrates and products, moderating concentration and reducing noncompetitive enzyme inhibition, a phenomenon termed "enzyme superactivity" [21].

Conclusion: Aqueous micellar catalysis enables efficient one-pot tandem chemo-enzymatic processes, expanding the scope of compatible reactions and improving enzymatic performance [21].

Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

Successful implementation of biocatalysis in research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biocatalysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Importance in Biocatalysis Research |

|---|---|

| Engineered Enzymes (Codexis, etc.) | Commercially available, optimized enzymes (e.g., transaminases, KREDs, IREDs) provide high performance for specific non-natural substrates and process conditions [17] [19]. |

| Cofactor Recycling Systems | Essential for economical use of cofactor-dependent enzymes (e.g., KREDs, ADHs). Common systems include glucose/glucose dehydrogenase for NADPH regeneration and isopropanol for ADH-catalyzed reductions [21] [19]. |

| Designer Surfactants (TPGS-750-M) | Form nanomicelles in water, enabling solubilization of organic substrates and compatibility between transition metal and enzyme catalysts in one-pot systems [21]. |

| Directed Evolution Platforms | A combination of molecular biology techniques, high-throughput screening robotics, and data analysis software is critical for rapidly optimizing enzyme properties like activity, selectivity, and stability [15] [19]. |

| Metagenomic Libraries | Provide access to a vast diversity of enzyme sequences from uncultured microorganisms, serving as starting points for discovering novel biocatalytic activities [15] [19]. |

The evidence from direct industrial case studies and hybrid catalytic systems firmly establishes the biocatalysis advantage. The superior specificity, safety, and sustainability of enzymes, combined with the power of protein engineering, enable more efficient and environmentally responsible synthetic routes. As the speed and precision of enzyme engineering continue to advance, biocatalysis is poised to transition from a complementary technology to a first-choice strategy for synthes complex molecules across the pharmaceutical and fine chemical industries [16] [19].

The selection between transition metal catalysis and biocatalysis is pivotal in modern chemical synthesis, especially for the pharmaceutical industry. This guide provides an objective comparison of these catalytic strategies based on three core performance metrics: Turnover, Selectivity, and Stability. While transition metal catalysts are renowned for their broad reactivity and high activity, biocatalysts excel in unparalleled selectivity and operating under mild, environmentally friendly conditions. The following data, protocols, and analysis offer a framework for researchers and development professionals to evaluate the most efficient catalyst for their specific applications.

Table 1: Core Performance Metrics at a Glance

| Performance Metric | Transition Metal Catalysis | Biocatalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Turnover Number (TON) | Often very high (e.g., 10^5-10^6 for Pd-catalyzed cross-couplings) | Variable; can be improved significantly via engineering (e.g., 7x increase in kcat achieved) [22] |

| Selectivity (e.g., Enantioselectivity) | Highly dependent on ligand design; can achieve >99% ee with sophisticated ligands | Inherently high; often >99% ee achievable with wild-type or engineered enzymes [22] [17] |

| Operational Stability | High thermal stability; may deactivate due to contaminant poisoning | Lower native stability; greatly enhanced via immobilization or directed evolution (e.g., 12x improved kcat/KM) [23] [22] |

| Typical Reaction Conditions | Often high temperature/pressure; organic solvents | Mild conditions (aqueous buffers, ~20-40°C, ambient pressure) [17] |

| Key Engineering Approach | Ligand design & synthesis | Directed evolution & immobilization [24] [22] |

Detailed Metric Analysis and Experimental Data

Turnover

Turnover measures the total number of reaction cycles a catalyst can perform before deactivation, directly linked to catalyst lifetime and efficiency.

- Biocatalysis: The maximum theoretical turnover can be limited by an enzyme's inherent stability. However, directed evolution can dramatically improve this metric. For instance, in the green synthesis of cardiac drugs, engineered enzyme variants achieved a seven-fold increase in catalytic rate (kcat) compared to their wild-type counterparts [22]. The Total Turnover Number (TTN) is a crucial metric for assessing the scalability of a biocatalyst, as it reflects the total product yield per catalyst molecule [23].

- Transition Metal Catalysis: Traditional metrics focus heavily on turnover frequency (TOF) and number (TON), which are often high for established reactions like cross-couplings. However, for a fair comparison with biocatalysts in industrial processes, metrics like productivity (g product/L/h) and achievable product concentration are increasingly recognized as more practical for scalability assessments [23].

Table 2: Experimental Turnover Data from Biocatalyst Engineering

| Enzyme Class | Wild-type Activity | Evolved Variant | Evolved Activity | Key Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytochrome P450 (CYP450-F87A) | Baseline kcat | CYP450-F87A | 97% substrate conversion [22] | High hydroxylation capacity for drug intermediates |

| Ketoreductase (KRED1-Pglu) | Baseline kcat | KRED-M181T | 7x increased kcat [22] | Enhanced rate for asymmetric reduction |

| Transaminase (TAm-VV) | Baseline kcat/KM | TA-V129L | 12x improved kcat/KM [22] | Greatly enhanced catalytic efficiency |

Selectivity

Selectivity, particularly enantioselectivity, is a paramount consideration in drug synthesis, as it directly impacts efficacy and safety.

- Biocatalysis: Enzymes possess chiral active sites that inherently facilitate high stereoselectivity. A prime example is the engineered ketoreductase KRED-M181T, which achieves 99% enantioselectivity in the synthesis of chiral alcohols for cardiac drugs [22]. This inherent precision often eliminates the need for protecting groups and costly separation steps, streamlining synthetic routes [17].

- Transition Metal Catalysis: Achieving high enantioselectivity requires sophisticated, and often expensive, chiral ligands. While selectivities exceeding 99% ee are possible, the performance is highly dependent on the specific substrate-ligand pairing. The Merck sitagliptin process showcases a direct comparison: a transition-metal-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation was successfully replaced by a biocatalytic transaminase process that provided a high-purity product with exceptional selectivity [17].

Stability

Stability refers to a catalyst's ability to retain its structure and function under process conditions, including temperature, pH, and solvent exposure.

- Biocatalysis: Native enzymes often have limited stability. The primary strategies for enhancement are directed evolution and immobilization. Directed evolution can produce variants, like the transaminase TA-V129L, with a broad pH tolerance (5.5–8.5), making them suitable for diverse industrial conditions [22]. Immobilization on solid supports simplifies recycling, contains enzymes in flow reactors, and frequently improves stability [23].

- Transition Metal Catalysis: Heterogeneous metal catalysts typically exhibit high thermal stability. However, they can be susceptible to deactivation through leaching, aggregation, or poisoning by contaminants. Stability is managed through careful catalyst design, ligand engineering, and process optimization.

Experimental Protocol: Directed Evolution for Enhanced Biocatalyst Stability and Selectivity

This methodology is a cornerstone of modern biocatalysis, enabling the tailoring of enzymes for industrial applications [22].

- Gene Library Construction: Create a diverse library of enzyme variants. This is achieved through error-prone PCR (random mutagenesis) or site-saturation mutagenesis (targeting specific amino acid residues).

- Expression and Screening: Express the variant library in a microbial host (e.g., E. coli). Grow colonies in high-throughput formats (96- or 384-well plates) and assay for the desired property (e.g., activity at elevated temperature, enantioselectivity).

- Selection of Hits: Identify variants showing improved performance relative to the parent enzyme.

- Iteration: Use the best-performing hits as templates for subsequent rounds of mutagenesis and screening until the performance targets (e.g., thermal stability, turnover number, enantiomeric excess) are met.

- Characterization: Purify the final evolved enzyme variant and kinetically characterize it to determine its improved parameters (kcat, KM, thermal half-life).

Catalyst Development and Evaluation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key stages and decision points in developing and evaluating catalysts for synthetic applications, highlighting the parallel approaches for biocatalysis and transition metal catalysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful catalyst evaluation and implementation rely on specific reagents and platforms. Below is a list of key solutions used in the featured experiments and the broader field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cinchona Alkaloid Organocatalysts | Catalyze asymmetric synthesis of chiral centers in N-heterocycles [25]. | Cinchonidine-derived squaramide catalyst for synthesizing pyrrolidinyl spirooxindoles with >93% ee [25]. |

| Engineered Transaminases | Catalyze the synthesis of chiral amines from ketones [17]. | Used in the commercial synthesis of sitagliptin and for producing chiral amine intermediates in β-blockers [22] [17]. |

| Engineered Ketoreductases (KREDs) | Enantioselective reduction of ketones to secondary alcohols [17]. | KRED-M181T variant for synthesizing chiral alcohols with 99% enantioselectivity [22]. |

| Immobilization Supports | Solid materials (e.g., polymers, silica) for enzyme attachment, enabling recycling and stability enhancement [23]. | Critical for containing enzymes in plug-flow reactors and improving operational stability in industrial processes [23]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Platforms | Automated systems for rapidly assaying thousands of enzyme or catalyst variants [22]. | Essential for directed evolution campaigns, allowing screening of large mutant libraries for improved performance [24]. |

| Metagenomic Libraries | Collections of genetic material from diverse environmental microbes, serving as a source of novel enzyme sequences [15]. | Used for biocatalyst discovery, providing access to a vast diversity of potential enzyme starting points for engineering [17]. |

Industrial Applications and Synthetic Methodologies in Drug Development

Transition metal catalysis and biocatalysis represent two powerful paradigms for constructing complex molecules in pharmaceutical and fine chemical research. While transition metal catalysis leverages the unique redox properties and coordination chemistry of metals like palladium, nickel, and copper to enable transformative bond-forming reactions, biocatalysis utilizes the exquisite selectivity and green credentials of enzymes. Historically, these approaches developed along parallel tracks with limited interaction due to perceived incompatibilities in reaction conditions. However, recent innovative strategies are successfully bridging this divide, creating hybrid methodologies that capture the strengths of both worlds [21]. This comparison guide examines the performance characteristics of these catalytic approaches, with a specific focus on asymmetric hydrogenation and cross-coupling applications, to provide researchers with objective data for informed methodological selection.

Performance Comparison: Transition Metal Catalysis vs. Biocatalysis

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics for Catalytic Methodologies

| Performance Metric | Transition Metal Catalysis | Biocatalysis | Hybrid Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Group Tolerance | Moderate to High [26] | High [21] | High (leveraging compartmentalization) [21] |

| Typical Yield Range | High (70-99%) [26] | Variable (plateaus common in buffer alone) [21] | Enhanced (up to 99%) [27] |

| Stereoselectivity (e.e.) | High (with chiral ligands) [28] | Excellent (>99.8%) [21] | Excellent (maintained from enzymatic step) [21] [27] |

| Reaction Medium | Organic solvents or aqueous micelles [21] | Buffer or water [21] | Aqueous micellar solutions [21] |

| Catalyst Tolerance | Sensitive to poisoning [26] | Sensitive to inhibitor buildup [21] | Enhanced compatibility via ligand design or compartmentalization [21] [27] |

| Typical Catalyst Loading | 0.5-5 mol% (Pd, Ni) [26] [27] | 1-20 mg/mL enzyme [21] | 1-5 mol% metal; 1-20 mg/mL enzyme [21] [27] |

Table 2: Comparison of Recent Advanced Catalytic Systems

| System | Reaction Type | Key Achievement | Representative Yield/e.e. | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd/Enzyme in Micelles [21] | Tandem Suzuki/Enzymatic Reduction | One-pot chemo-enzymatic cascade in water | 92% conversion; >99.8% e.e. | Optimization of surfactant concentration required |

| Cu/BCP-Lipase DKR [27] | Dynamic Kinetic Resolution | Atropisomeric BINOL synthesis via in situ coordination | 85% yield; 96% e.e. | Requires specific bathocuproine (BCP) ligand |

| Buchwald Ligands [26] | Cross-Coupling (C-N, C-C) | Coupling of unactivated aryl chlorides at room temperature | High yields reported | Ligand cost and air sensitivity can be issues |

| N-Heterocyclic Carbenes [26] | Cross-Coupling | Efficient coupling of sterically bulky substrates | High yields reported | High cost and optimization complexity |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

One-Pot Tandem Transition Metal-Biocatalysis in Micellar Media

Principle: This protocol enables sequential transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling followed by enzymatic asymmetric reduction in a single pot, using nanomicelles to compartmentalize catalysts and prevent mutual deactivation [21].

Materials:

- TPGS-750-M surfactant (2 wt% in 0.2 M phosphate buffer, pH 7): Forms nanomicelles that solubilize hydrophobic substrates and house catalysts.

- Palladium catalyst (e.g., Pd(PPh₃)₄ or Pd-AmPhos for Suzuki-Miyaura coupling).

- Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH, from suitable source such as Lactobacillus kefir or commercial preparations).

- NADPH cofactor or glucose/glucose dehydrogenase recycling system.

- Cross-coupling partners: Aryl halide and boronic acid.

- Ketone substrate: Functionalized acetophenone derivative.

Procedure:

- Micelle Formation: Prepare the reaction medium by dissolving TPGS-750-M (200 mg) in phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 7, 10 mL). Stir until a clear solution is obtained.

- Cross-Coupling Stage: Add the aryl halide (0.4 mmol, 1.0 equiv), boronic acid (1.2 equiv), and palladium catalyst (0.5-2 mol%) to the micellar solution.

- Reaction Monitoring: Stir the reaction mixture at room temperature or mild heating (35-40°C). Monitor the progress by TLC or GC/MS until the cross-coupling is complete (typically 2-6 hours). The hydrophobic product partitions into the micellar core.

- Enzymatic Reduction Stage: To the same pot, add the alcohol dehydrogenase (20 mg for 0.4 mmol ketone) and the NADPH cofactor (0.1 equiv with a recycling system, or 1.0 equiv without).

- Completion and Workup: Stir the reaction mixture at 25-30°C, monitoring by TLC or chiral HPLC until reduction is complete (typically 6-24 hours).

- Product Isolation: Extract the product with an organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate). The surfactant often facilitates easy phase separation. Purify the product by flash chromatography.

Key Validation Data: Conversion can be tracked by GC-FID or HPLC. Enantiomeric excess is determined by chiral HPLC or GC. Comparative control experiments in buffer alone typically show reaction plateaus at 30-80% conversion for lipophilic substrates, while the micellar system drives reactions to >90% completion [21].

Chemoenzymatic Dynamic Kinetic Resolution (DKR) with Copper Catalysis

Principle: This method describes the DKR of atropisomeric biaryls like BINOLs, combining a copper-based racemization catalyst with a lipase for selective acylation, achieving theoretical yields up to 100% [27].

Materials:

- Racemic BINOL substrate (e.g., 1a in the source study).

- Copper catalyst: CuCl (1 mol%).

- Ligand: Bathocuproine (BCP, L8, 1 mol%).

- Biocatalyst: Lipase LPL-311 immobilized on Celite.

- Base: Na₂CO₃ (indispensable for reaction efficiency).

- Acyl donor: Isopropenyl acetate or vinyl acetate.

- Anhydrous toluene as solvent.

Procedure:

- Catalyst Preparation: In a flame-dried Schlenk flask under nitrogen, combine CuCl (1 mol%) and bathocuproine ligand (1 mol%) in anhydrous toluene. Stir for 15 minutes to form the active copper complex in situ.

- Reaction Setup: To the catalyst solution, add racemic BINOL (1.0 equiv), Na₂CO₃ (1.5 equiv), and immobilized lipase LPL-311-Celite (by weight, optimized per batch).

- Initiation: Add the acyl donor (e.g., isopropenyl acetate, 2.0 equiv) to initiate the reaction.

- Process Monitoring: Stir the reaction mixture at the optimized temperature (e.g., 40°C). Monitor reaction progress and enantiomeric excess by chiral HPLC.

- Workup: Filter the reaction mixture to remove the immobilized enzyme and Celite. Concentrate the filtrate and purify the product by flash chromatography to yield the enantiomerically enriched acylated BINOL.

Key Validation Data: The success of the DKR hinges on efficient racemization. Control experiments without CuCl show ~45% yield and 96% e.e. (standard KR), while without the BCP ligand, yield increases but e.e. plummets to 60%, confirming ligand role in compatibility [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Advanced Catalytic Research

| Reagent/Catalyst | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| TPGS-750-M [21] | Benign surfactant for aqueous nanomicellar catalysis | Averages 50 nm micelles; biocompatible with enzymes; enables "solvent-free" organic synthesis. |

| Dialkylbiarylphosphine Ligands (e.g., SPhos, XPhos) [26] | Ligands for Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling | Bulky; promote oxidative addition & reductive elimination; enable room-temperature Suzuki couplings. |

| Bathocuproine (BCP) [27] | Ligand for Cu-catalyzed racemization in DKR | Provides π* orbitals for d-π* back-donation; enhances metal-ligand coordination; enables enzyme compatibility. |

| N-Heterocyclic Carbene (NHC) Ligands [26] | Ligands for challenging cross-couplings | Strong σ-donors; highly tunable sterics; effective for sterically hindered substrates. |

| Alcohol Dehydrogenase (ADH) [21] | Biocatalyst for asymmetric ketone reduction | High enantioselectivity; NAD(P)H-dependent; compatible with micellar media. |

| Lipase LPL-311 [27] | Biocatalyst for kinetic resolution and DKR | High enantioselectivity in acyl transfer; stable when immobilized on Celite. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualization

Diagram 1: Comparative catalytic cycles and their integration in a hybrid workflow. The micellar environment serves as a universal host, enabling both transition metal and enzymatic catalysis to proceed efficiently in sequence.

Diagram 2: Mechanism of Chemoenzymatic Dynamic Kinetic Resolution (DKR). The copper catalyst continuously racemizes the substrate, while the lipase selectively acylates one enantiomer, overcoming the 50% yield barrier of standard kinetic resolution.

The comparative analysis reveals that transition metal catalysis and biocatalysis are not mutually exclusive but are increasingly synergistic. Transition metal catalysis excels in enabling diverse carbon-carbon and carbon-heteroatom bond formations under versatile conditions, with recent advances in first-row transition metals and specialized ligands expanding its scope and sustainability [26] [27]. Biocatalysis offers unparalleled stereoselectivity and green credentials under mild aqueous conditions [21] [28]. The most significant innovation lies in hybrid systems that successfully integrate both approaches, using strategies like aqueous micellar catalysis and sophisticated ligand design to overcome historical incompatibilities [21] [27]. These hybrid systems represent a frontier in synthetic methodology, promising more efficient and sustainable routes to complex chiral molecules essential for pharmaceutical development and beyond. Future research will likely focus on expanding the repertoire of compatible metal-enzyme pairs, developing more sophisticated nanoreactors, and leveraging machine learning for the prediction of optimal hybrid catalytic systems.

The manufacturing of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the increasing adoption of biocatalytic methods for constructing complex chiral molecules. For much of pharmaceutical history, synthetic organic chemistry served as the primary engine for small molecule manufacturing, with early industrial enzymes finding only limited application in chiral resolution and simple hydrolysis reactions. [29] This landscape has changed dramatically as biocatalysis has moved from the periphery to the center of route design for small molecule APIs, enabled by AI-driven enzyme engineering, expanded substrate scope, and improved integration with traditional synthetic chemistry. [29]

This comparison guide examines two cornerstone biocatalyst families—ketoreductases (KREDs) and transaminases (TAs)—that have become indispensable tools for installing stereocenters with atomic precision. The momentum behind these enzymes reflects a confluence of industrial, regulatory, and economic forces that now make enzymatic catalysis a practical necessity rather than merely a green chemistry alternative. [29] Across the industry, biocatalytic routes routinely outperform conventional chemistry on key process metrics, including yield, selectivity, solvent consumption, and waste reduction, while offering more predictable scale-up and compliance advantages. [29]

Enzyme Classes: Mechanisms and Industrial Applications

Ketoreductases (KREDs): Precision Reduction Catalysts

Ketoreductases (KREDs), also known as alcohol dehydrogenases (ADHs), belong to the enzyme commission class EC 1.1.1.X and catalyze the enantioselective reduction of prochiral ketones to chiral alcohols. [30] These enzymes have become go-to biocatalysts for chiral alcohol synthesis in pharmaceutical manufacturing, with many commercially available options now accessible. [30] KREDs utilize the cofactor NAD(P)H as a reductant, requiring enzymatic recycling systems such as isopropanol (i-PrOH) as a cosubstrate or glucose dehydrogenase (GDH)/glucose systems to avoid stoichiometric cofactor use. [30]

The exquisite stereocontrol exhibited by KREDs enables the production of enantiopure alcohol intermediates with precision that often surpasses traditional chemical methods. For instance, in the synthesis of the Akt inhibitor ipatasertib, a commercially available KRED from Codexis performed a highly diastereoselective reduction while regenerating NADPH from i-PrOH as a terminal reductant. [30] This approach was favored over an alternative Ru-catalyzed asymmetric transfer hydrogenation route due to superior diastereoselectivity and challenges associated with purging residual metal catalysts. [30]

Transaminases (TAs): Chiral Amine Synthesis Specialists

Transaminases (TAs), particularly ω-transaminases, catalyze the transfer of an amino group from an amino donor to a ketone or aldehyde acceptor, enabling the synthesis of optically pure amines from the corresponding ketones. [31] These PLP-dependent enzymes (requiring pyridoxal 5′-phosphate cofactor) have emerged as powerful competitors to chemical methodologies for asymmetric amination. [31] The concise reaction, excellent enantioselectivity, environmental friendliness, and compatibility with other enzymatic systems have positioned TAs as transformative tools for chiral amine synthesis. [32]

Transaminases can be employed in two primary configurations: kinetic resolution of racemic amines (converting one enantiomer to ketone while leaving the desired amine untouched) or, more preferably, in asymmetric synthesis starting from prochiral ketones. [31] The latter approach offers theoretical 100% yield but presents thermodynamic challenges that require specialized engineering strategies to shift the equilibrium toward product formation. [31] The development of process-adapted enzymes and equilibrium-shifting methods has been crucial to the industrial success of this biocatalytic technology. [31]

Performance Comparison: Key Metrics and Industrial Case Studies

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Ketoreductases and Transaminases in API Synthesis

| Performance Metric | Ketoreductases (KREDs) | Transaminases (TAs) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Reduction of ketones to chiral alcohols | Amination of ketones to chiral amines |

| Typical Selectivity | Excellent diastereo- and enantioselectivity (>99% ee common) | Excellent enantioselectivity (>99% ee common) |

| Cofactor Requirement | NAD(P)H, requires recycling system | PLP, self-recycling; no additional system needed |

| Reaction Equilibrium | Generally favorable | Often unfavorable, requires shifting strategies |

| Typical Yields | High (85->99%) | Moderate to high (32-99%), substrate-dependent |

| Industrial Example | Ipatasertib intermediate (Genentech/Roche) | Sitagliptin (Merck/Codexis) |

| Scale Demonstrated | Multikilogram scale | Commercial manufacturing scale |

| Key Advantage | High selectivity for bulky groups | Direct amination avoiding metal catalysts |

Table 2: Industrial Case Studies Demonstrating Implementation Scope

| API/Intermediate | Enzyme Class | Company | Scale | Key Result | Advantage Over Chemical Route |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sitagliptin | Transaminase | Merck/Codexis | Commercial | >99% ee, waste reduction | Eliminated heavy metal catalyst, shorter route |

| Ipatasertib Intermediate | Ketoreductase | Genentech/Roche | Multikilogram | High diastereoselectivity | Avoided Ru purging challenges |

| Navoximod Intermediate | Ketoreductase | Genentech/Roche | 50 g scale | High yield, selectivity | Selective reduction of cyclohexanone motif |

| FXI Inhibitor Intermediate | Ketoreductase | Novartis | Multikilogram | Excellent yield and ee | Operational simplicity with i-PrOH cosolvent |

| ROMK Inhibitor Intermediate | Ketoreductase | Merck & Co. | Multikilogram | High yield, excellent ee | Enabled versatile chiral epoxide building block |

The quantitative comparison reveals distinct performance characteristics for each enzyme class. KRED processes consistently achieve high yields (often >90%) and excellent stereoselectivity across diverse substrate types, with particular strength in reducing ketones flanked by moderately sized substituents. [30] The industrial implementation of KREDs has been facilitated by the commercial availability of numerous enzyme variants and well-established cofactor recycling systems.

Transaminases demonstrate equally impressive enantioselectivity but face thermodynamic constraints that can limit yields in asymmetric synthesis applications. [31] The most significant limitation for TAs has been the amination of sterically demanding "bulky-bulky" ketones, though protein engineering has created breakthrough catalysts such as the engineered transaminase from Arthrobacter sp. that enabled the efficient synthesis of sitagliptin. [31] This landmark achievement demonstrated that a biocatalytic process could not only match but exceed the performance of state-of-the-art chemical catalysis (rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation) in a commercial, regulatory-compliant context. [29]

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Ketoreductase Protocol for Chiral Alcohol Synthesis

The following protocol represents a generalized procedure for KRED-catalyzed asymmetric ketone reduction, based on published industrial examples: [30]

Reaction Setup: Charge the reactor with ketone substrate (1.0 equiv), appropriate buffer (typically phosphate or triethanolamine, 100-500 mM, pH 6.5-8.0), and co-solvent if needed (typically i-PrOH or DMSO, <20% v/v). Add NAD(P)+ (0.1-1.0 mol%) and KRED enzyme (1-10 g/L). For recycling systems utilizing GDH/glucose, include glucose (1.5-2.0 equiv) and GDH (0.1-1.0 g/L).

Process Parameters: Maintain temperature at 25-45°C with constant agitation. Monitor reaction progress by HPLC or GC. Typical reaction times range from 4-48 hours depending on substrate concentration and enzyme loading.

Workup and Isolation: Upon completion, extract product with ethyl acetate or separate layers if biphasic system used. Concentrate and purify by crystallization or chromatography to obtain chiral alcohol.

Key Process Considerations: The Genentech/Roche team operating a KRED process for an ipatasertib intermediate employed high substrate loading as a slurry-to-slurry reaction to achieve high yield while mitigating substrate degradation. [30] The Novartis team implementing a KRED process for a Factor XI inhibitor intermediate utilized i-PrOH as cosubstrate, sacrificial reductant, and cosolvent to avoid the need for continual pH adjustment during scale-up. [30]

Standard Transaminase Protocol for Chiral Amine Synthesis

The following generalized protocol for TA-catalyzed asymmetric amination is adapted from published procedures for sitagliptin synthesis and related transformations: [31] [33]

Reaction Setup: Charge the reactor with prochiral ketone substrate (1.0 equiv), amine donor (typically isopropylamine, 2-10 equiv for equilibrium shifting), appropriate buffer (typically triethanolamine, 100 mM, pH 9-10), DMSO or other cosolvent (10-50% v/v for substrate solubility), and PLP cofactor (1 mM).

Enzyme Addition: Add transaminase enzyme (soluble or immobilized, 1-20 g/L). For immobilized systems, the enzyme may be packed in a fixed-bed reactor for continuous operation.

Process Parameters: Maintain temperature at 30-50°C with constant agitation (for batch) or controlled flow rates (for continuous processes). Monitor reaction progress by HPLC or GC.

Equilibrium Shifting Strategies: Critical for high conversion in transaminase reactions. Effective approaches include: (1) Using excess amine donor (e.g., isopropylamine) with acetone removal by evaporation; [31] (2) Coupling with lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) to remove pyruvate byproduct; [31] (3) Employing alanine dehydrogenase to recycle pyruvate back to L-alanine. [31]

Workup and Isolation: Upon completion, separate enzyme if immobilized system used. Extract product, concentrate, and purify by crystallization to obtain chiral amine.

Key Process Considerations: The Merck/Codexis process for sitagliptin utilizes an engineered transaminase capable of accepting the "bulky-bulky" ketone substrate and employs isopropylamine in excess to drive the reaction to completion. [31] Recent immobilization approaches, such as covalent binding to epoxy-functionalized methacrylic resins, have demonstrated improved stability and reusability for transaminase biocatalysts. [33]

Visualization of Biocatalytic Processes

Diagram 1: Comparative reaction pathways for KRED and transaminase biocatalysts, highlighting cofactor requirements and key process considerations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biocatalysis Experimental Work

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| KRED Enzymes | Catalytic reduction of ketones | Commercially available from Codexis, c-LEcta, etc.; screen multiple variants for optimal activity |

| Transaminase Enzymes | Catalytic amination of ketones | Available from specialized suppliers (e.g., Enzymaster); consider selectivity (R vs S) |

| NAD(P)+/NAD(P)H | KRED cofactor | Catalytic quantities sufficient with recycling systems |

| Pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (PLP) | Transaminase cofactor | Typically used at 1 mM concentration; essential for activity |

| Isopropyl Alcohol (i-PrOH) | KRED cosubstrate/reductant | Serves as terminal reductant in KRED systems; also used for equilibrium shifting in TAs |

| DMSO | Cosolvent | Improves solubility of hydrophobic substrates; typically 10-50% v/v |

| Glucose Dehydrogenase (GDH) | Cofactor recycling enzyme | Used with glucose for NAD(P)H regeneration in KRED systems |

| Amino Donors | Amino group source for TAs | Isopropylamine common; alanine alternatives with recycling systems |